Introduction

The Rohingya refugee crisis, which has been ongoing since 2017, has once again attracted international attention. While the conflict in Gaza or Ukraine has become the world’s latest focus, reports indicate a new wave of Rohingya refugees fleeing the oppression of Myanmar’s military junta government. They sail dangerously across the Andaman Sea in makeshift boats to escape, thus raising global concern about the crisis. In 2024, UNHCR reported that there are 1.35 million people with refugee status, people in refugee-like situations, and asylum seekers stemming from this humanitarian conflict. Refugees are fleeing Myanmar with the hope that neighbouring countries will accept them, particularly Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which have Muslim-majority populations. In November 2023, nearly two thousand additional Rohingya refugees landed in Aceh, Indonesia, in dire condition and in need of food. Beyond the situation in Myanmar, several factors fueled the influx of refugees. Overcrowding in shelters in Bangladesh and favourable weather conditions facilitated sea travel. Consequently, projections indicate an increased influx of refugees to Aceh in 2024.

While there is empathy from many in the countries with an influx of refugees, a growing faction is advocating for action against more coming in, and this group is swelling in popularity. This growing movement vehemently opposes the arrival of refugees, their frustration stemming from a sense of exhaustion with continual assistance efforts from their own governments. The constant influx of refugees and news reports that they have disturbed public order has given further rise to hateful sentiments. These anti-Rohingya supporters spread messages in various forms online using memes and hateful narratives to galvanise more locals to their anti-refugee cause. The Austronesian supremacist narrative is used to reject the Rohingya, who are perceived as inferior compared to the Indonesian and Malaysian people. Acronyms and extremist terms are also used, such as TRD (Total Rohingya Death), which advocates genocidal intent. Further, there is also a conspiracy narrative alleging that it was UNHCR that brought the refugees into Indonesia. Therefore, this Insight aims to investigate the extremist sentiments spread online surrounding Rohingya refugees in Indonesia and Malaysia in an effort to address the misinformation and harm surrounding these narratives.

Austronesian Supremacy Rhetoric and Anti-Rohingya Sentiment

Much of the anti-Rohingya sentiment produced and circulated on social media is based on the narrative of Austronesian supremacy. In this previous insight, the existence of this ideology was mentioned, which essentially emphasises the superiority of the Austronesian race compared to other peoples. The emergence of this belief is inspired by the white supremacist narrative of the West. They believe that prior to settling in the Pacific islands, their ancestors had sailed to and from the islands and were, therefore, believed to be inherently skilled and physically strong. Throughout history, Austronesian descendants have also resisted colonisation and succeeded in becoming independent nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia today. In this case, Austronesian Supremacists are trying to show that the Austronesians are superior in all aspects of life in comparison to the Rohingya people. In their view, the Rohingya are seen as outcasts who do not deserve to live in the same place as the Austronesians.

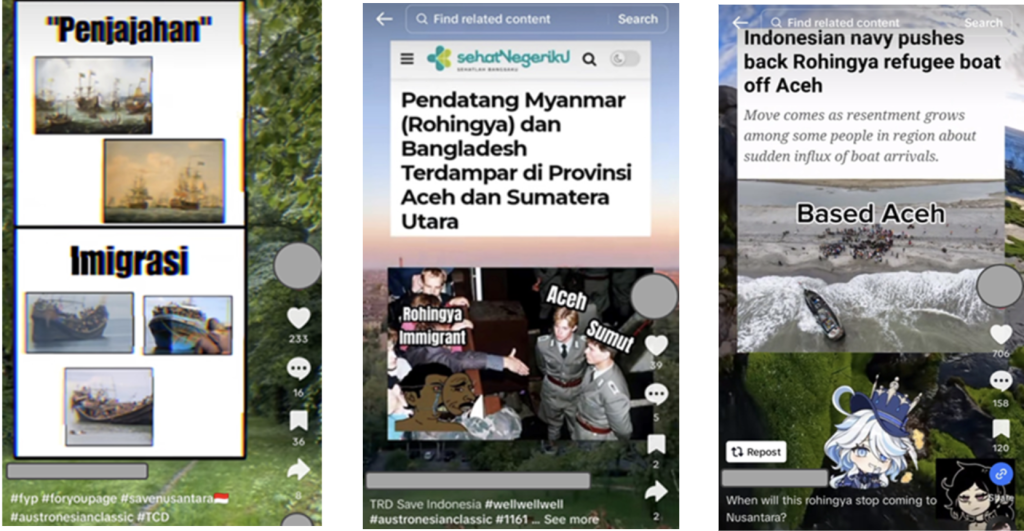

Figs. 1-3 (left to right): The usage of Austronesian supremacy narrative on TikTok platform against Rohingyas

The three figures above were found on TikTok, a platform rife with far-right propaganda. In the first picture, the video tries to show that “colonisation” and “immigration” are the exact same thing. The paintings that illustrate colonisation refer to the arrival of Europeans in the Nusantara before colonising it. Underneath, there is a picture of the boats used by the Rohingya to seek asylum. This relates to the anti-immigrant and anti-Rohingya narrative that if too many Rohingya refugees are welcomed, they will eventually dominate and drive out the local population.

The second picture shows the refusal response of the people of Aceh and North Sumatra to the arrival of Rohingya refugees, represented using wojak characters and East German border police at the Berlin Wall. Similarly, Fig. 3 shows a snippet of a news headline from Aljazeera that praises the Indonesian navy for turning away a refugee boat. The action is labelled as “Based Aceh” by the content creator while questioning when Rohingya refugees will stop coming to the archipelago. Additionally, this narrative on TikTok is accompanied by the hashtags #austronesianclassic and #savenusantara.

Fig. 4: Anti-Rohingya sentiment becoming prevalent in several countries

Fig. 4 shows the widespread presence of anti-Rohingya sentiment by featuring several country flags. Myanmar, where the Rohingya crisis first began, as well as Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, are the countries that have received the most amount of refugees due to their proximity to Myanmar. The figure implies justifying the genocide committed by the Myanmar government against the Rohingyas and urges other countries to repudiate and stop accepting the Rohingyas.

Figs. 5 & 6: Meme variations of the anti-Rohingya sentiment

Memes are just one medium used by online extremists to spread their message. As seen in Fig 5, extremists on TikTok used an anti-alcohol poster from the Soviet Union to replace depict the UNHCR ‘giving’ Rohingya refugees to ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), only to be rejected by the organisation. Aside from that, the same group also created a logo for the #ARA (Anti-Rohingya Action) movement with the ASEAN symbol in the centre, as seen in Fig. 6. Moreover, the acronym #TRD (Total Rohingya Death) was also used to denote hatred, violence, and intent to genocide the Rohingya. Existing acronyms in Western extremist groups also inspire this acronym, such as TJD (Total Jewish Death) or TMD (Total Muslim Death). To add to the characterisation, they also created a wojak Rohingya character who pleads for acceptance but is vehemently rejected by Malaysian society. Another surprising element is that Chinese and Indian characters are also depicted alongside the Malaysian character, even though they are often the targets of the same kind of xenophobia.

The Strike on Instagram Comments & Conspiracy Theory

The proliferation of hatred towards the Rohingya can also be observed through Instagram. Looking at the Instagram account of @unhcrindonesia, there is a post that discusses the Rohingya refugee crisis and the misinformation circulating. It has garnered a vast number of engagements, reaching more than 46,000 comments. The post intends to clarify the comments from fake TikTok accounts impersonating the official account of UNHCR Indonesia that they deliberately brought Rohingya refugees to Indonesia. Needless to say, Indonesians took their official statement for granted on social media. As such, the comment section of the post was flooded with questions and accusations that UNHCR Indonesia was conspiring to bring in Rohingya refugees in order to displace local Indonesians from their homes slowly.

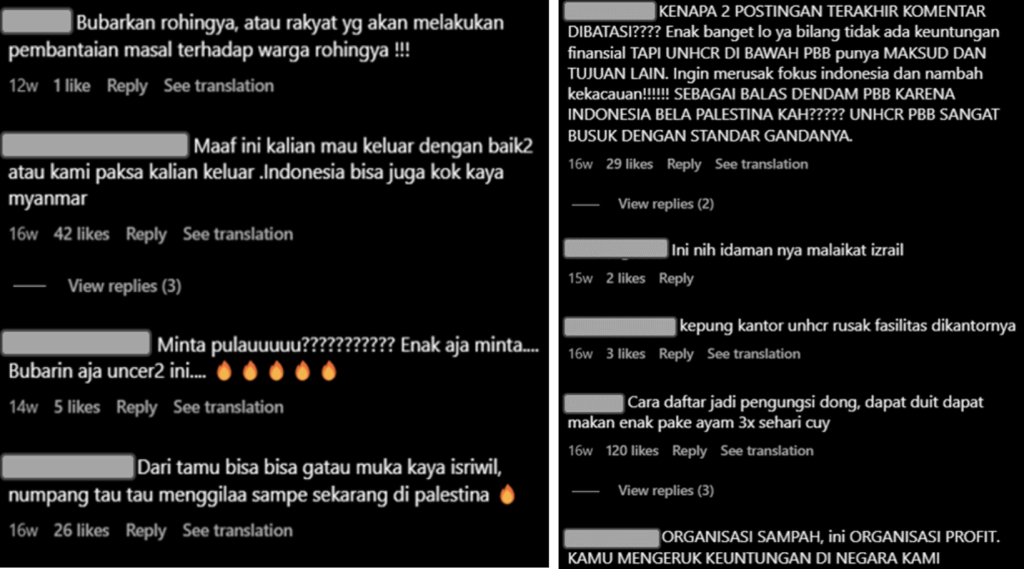

Fig. 7 & 8: Screenshots of the several hate comments flooding UNHCR’s post

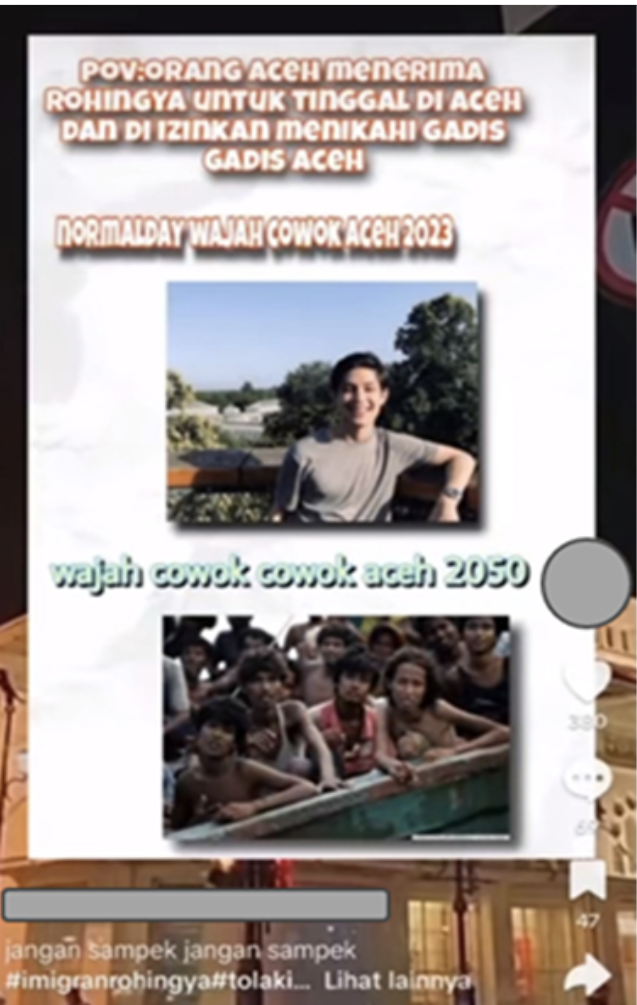

Fig. 9: Rohingya version of the Great Replacement conspiracy theory

Through this conspiracy, we are reminded of the existing Great Replacement conspiracy theory. Evidently, this theory has been re-adopted to reflect the concerns in this region, such as rejecting the presence of Rohingya in Aceh. The meme in Fig. 8 shows Aceh’s present and future situation according to the conspiracy theory. In 2023, the people of Aceh were still of Austronesian descent. However, it purports that when the Rohingya are accepted by the Acehnese and allowed to procreate with the locals, in 2050, the Acehnese will be replaced by the Rohingya population.

Violent Extremism Realised

With many anti-Rohingya narratives circulating and misinformation on social media, on 27 December 2023, a group of Acehnese students violently mobilised following their online radicalisation. They stormed a temporary shelter in a protest to drive the refugees out of Aceh. A video shows them rioting by burning tyres, kicking refugees’ belongings, and chanting “Reject Rohingya in Aceh”. The students managed to get the refugees on a truck to be allocated to the Red Cross headquarters and the Aceh Foundation Building. UNHCR later condemned the attack as the result of a coordinated online campaign to spread misinformation, disinformation, and hatred towards refugees.

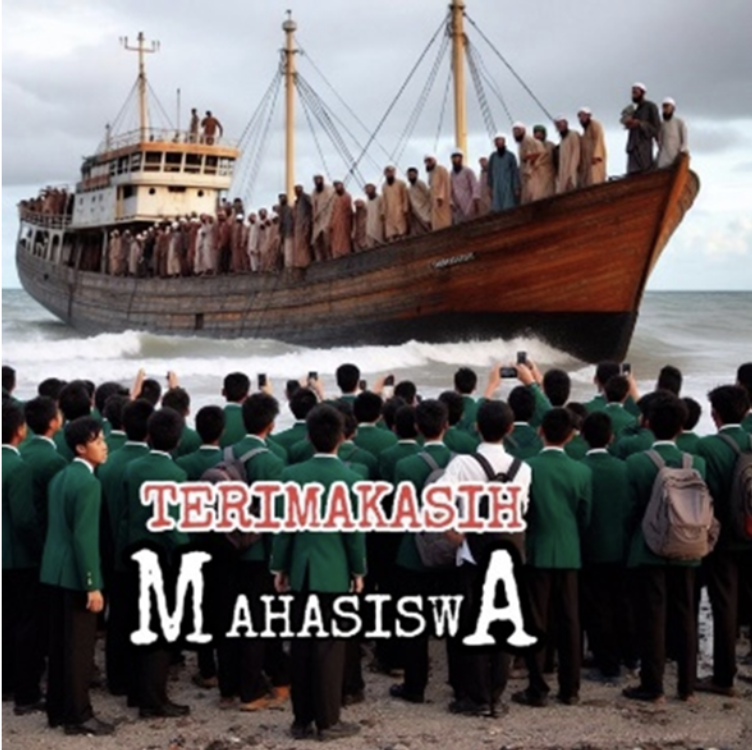

Fig. 10: AI generated image relating to the shelter incident by students in Aceh

Online extremists are also using emerging technologies like AI to further their campaigns of disinformation. AI generates Fig. 10 in relation to the actions of those students. It shows students wearing green uniforms and a boat on the shore filled with illustrations of Rohingya refugees. The students are standing with their mobile phones in hand, ostensibly documenting the scene as they drive the Rohingya back out to sea. The illustration was accompanied by the words “TERIMAKASIH MAHASISWA”, which thanked the students for their actions and suggested that the refugees’ forced displacement was the right thing to do. Another image circulating on TikTok shows an Indonesian flag with a wojak character that depicts saying no more to the presence of migrants. From Fig. 11, a symbol that is identical to neo-Nazis, namely the SS Lightning Bolts, can also be observed. This further explains the similarity of the superiority ideology adopted by online right-wing extremists in Indonesia.

Fig 11: “No More Migrants” propaganda image with added lightning bolts symbol

Conclusion

The Rohingya refugees, who have suffered genocide and expulsion in Myanmar, are now experiencing the same xenophobia, discrimination, displacement, and attacks in the places where they have fled. Various sentiments produced with supremacy aesthetics eventually led to the extremist violence that Rohingya refugees have received. In relation to the recent 2024 presidential elections in Indonesia, the Rohingya refugee crisis was used to further a populist narrative, as expressed by President-elect Prabowo Subianto. He expressed that he would prioritise the Indonesian people over the refugees and that the aid given to the Rohingya should not cost the Indonesian people themselves. His statement raises the question of how the future government will make policies to address the issue of Rohingya refugees, both online and offline.

To address this issue, it is necessary to collaborate with social media platforms to tighten content management in order to detect extremist and disinformation-ridden content. As UNHCR had mentioned previously, there is a coordinated campaign using online platforms to spread hatred against these refugees.

The relevant regional organisation, ASEAN, must also be aware of this and start looking for practical and feasible solutions. Although possible threats are long-term and do not necessarily endanger the integrity of the ASEAN community, it is necessary to recognise and anticipate the growing threat of right-wing extremism. Furthermore, it is imperative for all ASEAN members to unite in countering this divisive narrative while actively working towards the realisation of human rights for the Rohingya. This responsibility is especially crucial for Indonesia and Malaysia, as prominent voices within ASEAN, as these sentiments predominantly originate from these nations.