Introduction

Since its launch in 2017, TikTok’s user base has grown significantly from 347.1 million to 1.7 billion in 2022. Many are drawn to TikTok’s concise video format and editing options, which enable users to create various types of videos with ease. As such, the type of content on the platform has diversified, including the emergence of right-wing propaganda. TikTok has become one of the easiest social media platforms to find such content, as users can type in certain keywords on the search bar to find videos, pictures, music, and text posts designed for virality. The propagation of far-right propaganda online is a cause for concern, particularly on an amplification platform like TikTok, whose algorithms are designed to reach a broad audience.

This Insight aims to expand the discussion on TikTok’s far-right content. It explores how the idea of racial superiority is being propagated via various trends and rhetoric found on the platform. In particular, the phenomenon of far-right content spreading from Western countries and later being adopted by users elsewhere – in this case, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Existing Eurocentric supremacist narratives such as ‘Yup Anotha Aryan Classic!’ and ‘#saveeurope’ are translated and revised according to the sociocultural and political conditions of their countries.

From #aryanclassic to #austronesianclassic

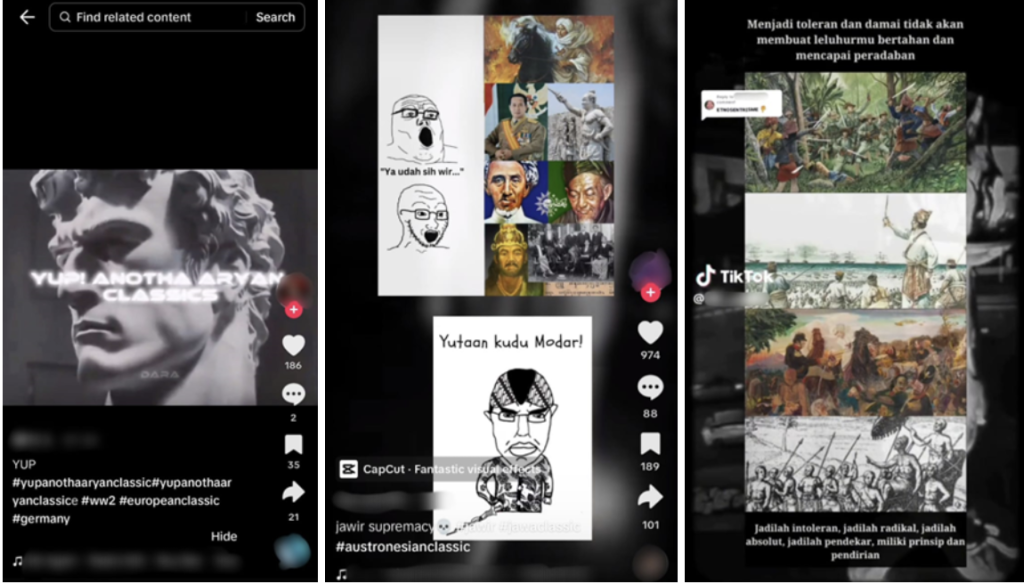

Figs.1-3: Depiction of the original version of #aryanclassic (left) and depictions of #austronesianclassic (centre and right)

Initially, the rhetoric and slogans observed in far-right TikToks were rooted in Western white supremacist or ultranationalist ideologies. However, the platform’s algorithm played a pivotal role in curating the ‘For You Pages’ (FYP) of users around the world by showcasing content that other users have engaged with through likes, views, and shares.

As a result, popular far-right propaganda gained prominence internationally, with Southeast Asia being a notable case in point. As Weimann and Masri point out, far-right extremist content is crafted to incorporate local aesthetics, words, and historical narratives. This adaptability enables some users in Southeast Asia to identify with the messages displayed, leading to growing support for a more ethnically homogeneous Southeast Asia.

As mentioned previously, the prevailing rhetoric on social media is often a reflection of the creator’s perception of reality. For instance, if Aryans are perceived as superior in Europe, then the same logic is applied to Austronesians in Southeast Asia. Individuals who hold this view consider themselves indigenous and deserving of being the sole inhabitants of Austronesian territory. Contrary to popular belief, Austronesians are not native inhabitants of Southeast Asia; instead, they are a prehistoric population originating from Taiwan who migrated by way of maritime routes. Traces of their voyage can be found in the languages and cultures of Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

Fig. 1 shows the use of the phrase “Yup! Anotha Aryan Classics”, a trend that gained notoriety on TikTok for promoting racist and white supremacist ideas by referencing fascist ideas and aesthetics. These include the sculptural aesthetics of Arno Breker, the official sculptor of the Nazi party. Fig. 2, through the hashtag #austronesianclassic and the popular meme character ‘Wojak’, attempts to show historical Indonesian figures of Javanese origin. Here, the character ‘Chud Wojak’ is wearing traditional Javanese clothing and uttering the phrase “Yutaan kudu Modar!” – the Javanese language translation of the “Millions must die” rhetoric of the Great Reset conspiracy theory. This suggests an idea of Javanese supremacy in Indonesia. Fig. 3 employs historical paintings from Indonesia to convey a similar form of rhetoric. Surrounding these paintings are sentences that encourage viewers to embrace intolerance, radicalism, and a warrior spirit, implying that these traits are necessary to survive and achieve a state of civilisation and superiority.

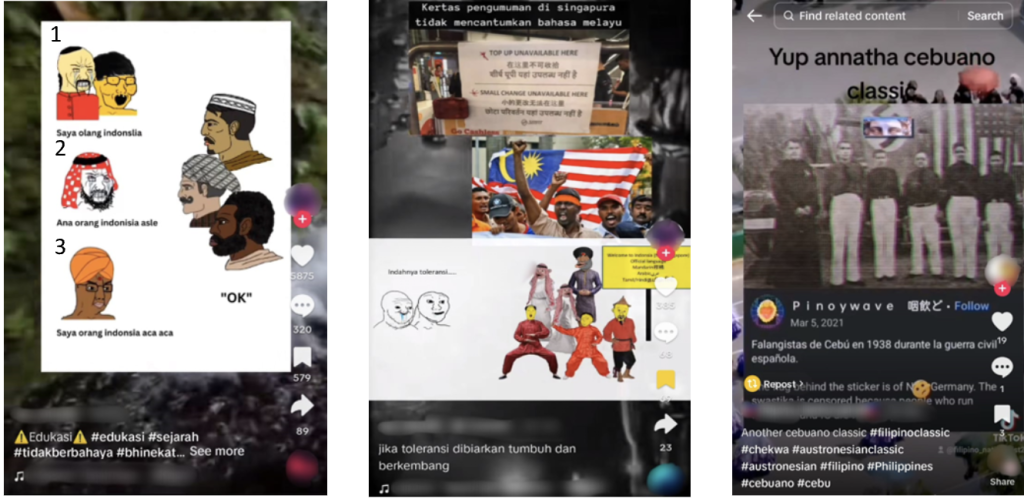

Figs. 4-6: Various forms of #austronesianclassic: Indonesia (left), Malaysia (centre), the Philippines (right)

The use of ‘Wojak’ characters is common when conveying far-right messages. Fig. 4 shows three exaggerated characters of Chinese, Arab, and Indian descent. Confronting them are Austronesian people who claim to be indigenous to Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines and reject the legitimacy of those of non-Austronesian, non-indigenous heritage. In reality, Southeast Asia’s history is deeply multicultural. In the past, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines were the world’s maritime trade routes, bringing traders from China, the Middle East, and India to the region. Over the centuries, these ethnic groups integrated with the previously migrated population, contributing to the rich diversity of Southeast Asia today.

In a more extreme piece of content, Fig. 6 shows what appears to be a Filipino Facebook group called ‘Pinoywave’ promoted through TikTok (Pinoy is an informal term for Filipinos). The group embraces the same far-right visual aesthetic of ‘fashwave’, characterised by neon colours and video game aesthetics. It also carries other localised rhetoric such as “Yup annatha [sic] cebuano classic”. Cebuano is an Austronesian language commonly spoken in the southern Philippines. Pinoywave and its localised forms can be viewed as an online Austronesian-Filipino movement promoting superiority and ultranationalist views of the Philippines.

From #saveeurope to #saveindonesia

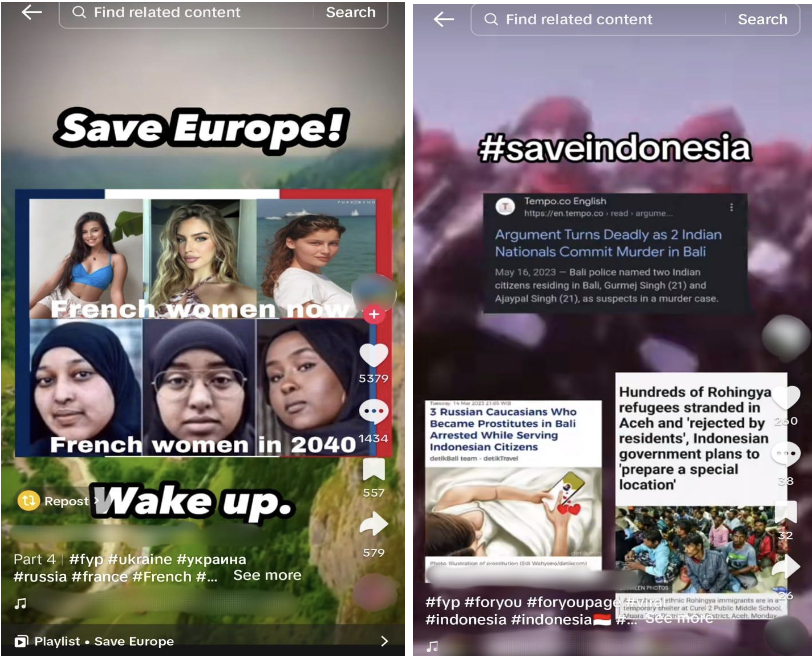

Figs. 7 & 8: #saveeurope (left) and #saveindonesia (right)

The common call among white, European far-right activists to ‘Save Europe’ from the nefarious influences of immigration and Islam (Fig. 7) has an Indonesian counterpart. The “saveindonesia” hashtag speaks of dislike and even hatred towards foreign tourists and Rohingya refugees fleeing genocide in Myanmar. Combined with the video of the Indonesian military parading in the background, it demonstrates a strong rejection of foreigners in what they perceive to be their native land (Fig. 8). The content from both regions shares a common objective: expelling unwanted individuals from their respective countries.

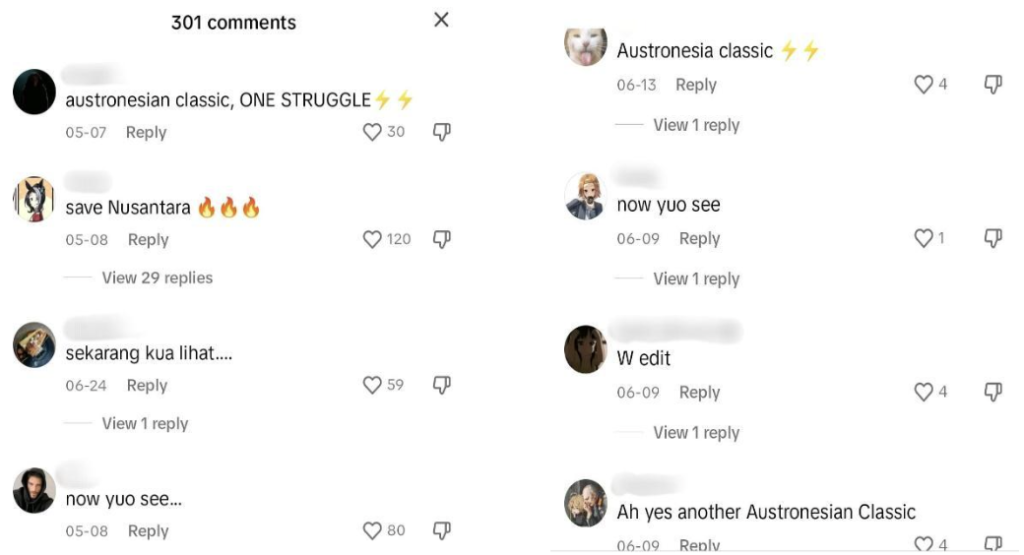

Fig. 9: Comments by various users found in the related TikTok videos

The comment section of these videos reveals the imitation of other far-right rhetoric circulating on TikTok. The phrase “now yuo see” has been increasingly associated with far-right dog whistles and antisemitic trends on TikTok like Gnome Hunting. This misspelling is used among those who see themselves as ‘enlightened’ white Europeans, compared with other inferior races or ‘normies’ who would say ‘you’. Replicating this trend, users in the observed posts translate the phrase into Indonesian (“sekarang kua lihat”), intentionally misspelling ‘kau’ as ‘kua’.

Conclusion

The #austronesianclassic’ and #saveindonesia hashtags are illustrative examples of the globalising influence of Western far-right propaganda. The rapid growth of the internet and social media has played a pivotal role in this phenomenon. As white supremacist rhetoric is adapted and evolves to promote Austronesian supremacy, it retains the same characteristics: xenophobia, disdain towards diversity, and ultranationalism. It is imperative for regulators, especially in Southeast Asia, to address and mitigate the influence of far-right propaganda on platforms like TikTok, which, although often associated with dancing and singing, can harbour content that threatens multiculturalism.

Jonathan Suseno Sarwono is an undergraduate International Relations student at Universitas Diponegoro. Currently, his study interest is focused on security, online extremism, and cybercrime.