This Insight is part of GNET’s Gender and Online Violent Extremism series, aligning with the UN’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence.

This Insight will analyse the monetisation strategies employed by online extremist actors to generate profit by promoting misogyny and violence against women. It investigates the financial dynamics at play, focusing on key actors, the narratives they deploy, and the tactics they utilise to operate as a scalable business model.

Online misogyny has become a central concern for gender-based violence (Human Rights First 2024), evolving into a profitable digital economy that spans mainstream platforms, alternative ecosystems, and influencer networks. The “manosphere” often overlaps with far-right, white supremacist, religious supremacist, conspiratorial, and violent offline ecosystems, framed through “red pill” rhetoric that positions misogyny as a form of ideological wake (ICCT 2023). This convergence is visible across several subcultures. Tradwife and “womanosphere” communities glamorise hyper-traditional gender roles, normalise inequality, and frame submission as empowerment (New Yorker 2024; The Guardian 2025). Anti-feminist women influencers in South Korea amplify manosphere ideologies and attract substantial online followings (GNET 2023). Many of these narratives interact with extremist frameworks and are used to legitimise online harassment, disinformation and gender-based hostility (Lee 2025).

Monetisation and Supporting Infrastructure

Misogynistic influencers exploit commercial systems that reward the deliberate use of hostility to produce rapid surges in engagement (She Persisted 2023). Such dynamics link antagonism with monetisation, creating an information environment where misogynistic or violent rhetoric is a financial incentive. These engagement signals often expose users to extremist narratives and shift them from general hostility towards explicit ideological recruitment (ICCT 2023).

Programmatic advertising prioritises provocative content because it increases revenue for creators and intermediaries across the supply chain. Even when platforms adopt restrictions, algorithms may continue to promote the content, directing users to external sites or private communities where creators retain control (ICCT 2023). The yet unresolved lack of transparency in the online advertising ecosystem prevents most companies from knowing where their adverts appear, enabling unintended support for misogynistic or extremist-aligned content.

Off-platform tools redirect audiences to closed groups or private communities to maintain continuity during suspensions or restrictions (Richard Rogers, Media Studies – University of Amsterdam 2020). This helps creators preserve reach and create new revenue streams without relying on platform algorithms. Additionally, email requires minimal to no verification or content checks.

In these private or unmoderated channels, donations, subscriptions and direct payments through services such as Subscribestar, Substack, or cryptocurrencies can also bring in significant income for violent or misogynistic content. Often, branded merchandise reinforces brand identity and misogynistic messaging and generates yet another revenue stream (Minderoo Foundation 2025). Courses and coaching programmes offer further monetisation opportunities, using public platforms to attract audiences before shifting them into paid environments (Tech Policy Press 2024). These courses are creator-designed with no content moderation. Referral codes and affiliate partnerships create additional incentives by rewarding creators for directing audiences to consumer products or financial services (The 19th 2025).

Independent websites and online shops rely on commercial hosting providers and payment processors that rarely enforce policies addressing gendered rhetoric. This lack of transparency enables creators to continue selling goods and processing payments even if social platform restrictions are in place, a strong example of how limited transparency across digital advertising and e-commerce systems shields revenue-generating activity from scrutiny.

Moderation challenges further reinforce this ecosystem. Automated systems struggle to recognise contextual or coded misogyny. Additionally, many platforms intervene sparingly, even in cases involving explicit threats. There are numerous examples of violent gender-based content remaining online despite breaching platform rules (She Persisted 2023), of which notable examples include the restoration of Andrew Tate’s X content in 2023 (BBC 2023) and the lengthy waiting time for support requests for digital abuse (Refuge UK 2022) that average longer than a week, with only half receiving a reply. This cycle preserves the conditions that enable misogynistic content to circulate and generate profit.

Key Actors and Their Online Ecosystems

Misogynistic actors advance a worldview that positions women as threats to social order, moral stability, or male identity. This style of gendered hostility is a feature of extremist ideology, reinforcing narratives central to white nationalism, Christian nationalism, anti-LGBTQ+ hatred and conspiratorial thinking (ICCT 2023; ADL 2018; SPLC ). Misogyny creates emotional entry points through grievance, humiliation, and perceived loss, making ideological transitions into racism, antisemitism, or authoritarian politics easier to justify. As a result, misogynistic content acts as an accessible on-ramp that unifies audience frustration with broader violent ideologies.

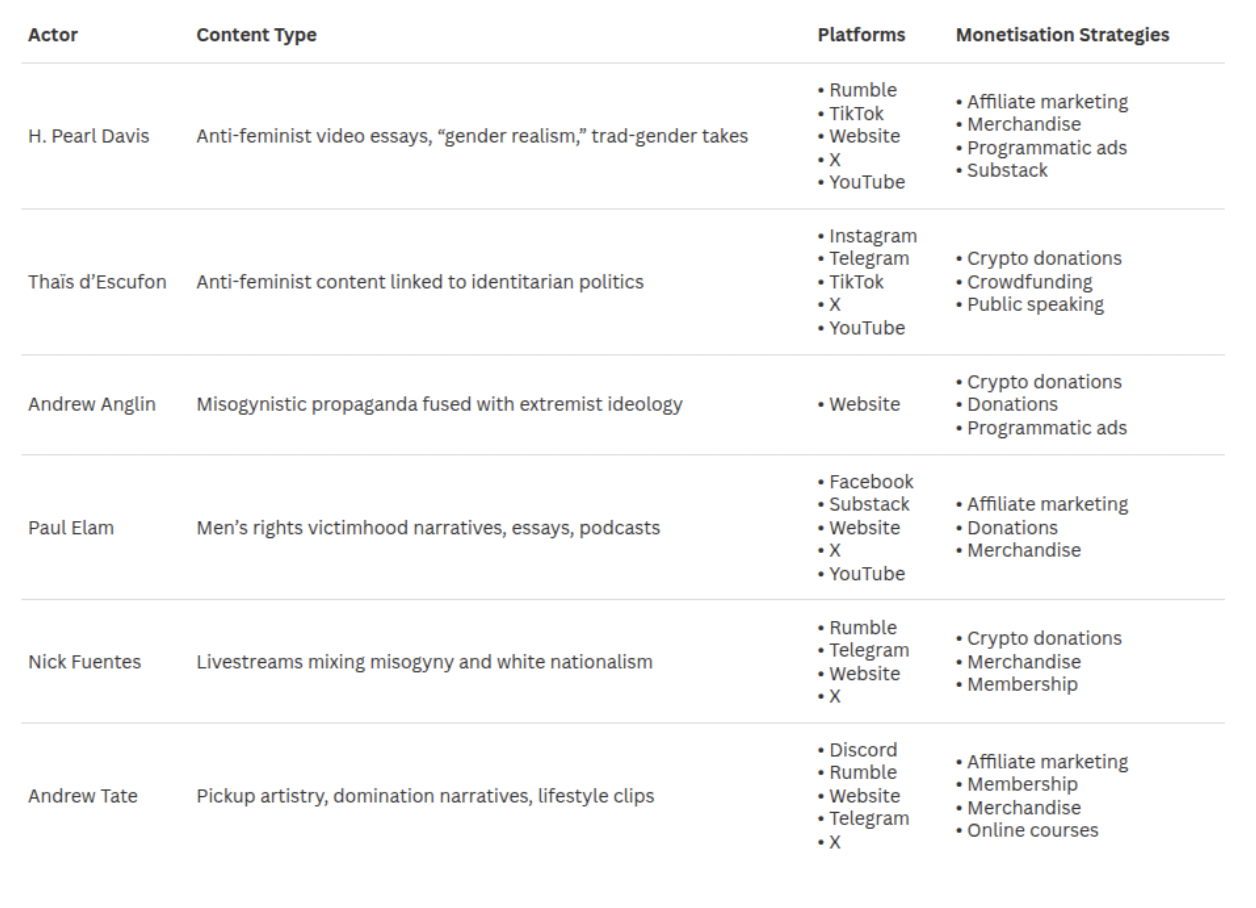

Figure 1: Actors analysed in this Insight and their monetisation strategies

Hannah Pearl Davis is a high-reach anti-feminist influencer whose content blends “traditional femininity” with narratives of women as morally degraded and responsible for social decline. Davis calls for a return to rigid gender hierarchies, opposes women’s autonomy and is sceptical of legal protections such as divorce reform (Silman 2025; Dodgson 2023). Her content is frequently recommended alongside overtly misogynistic and conspiratorial creators (ICCT 2023). While she avoids explicit extremist framing, her narratives reinforce male-supremacist rhetoric that sits adjacent to far-right mobilisation.

Figure 2: Hannah Pearl Davis reacting to a Charlie Kirk’s video and equating abortion to murder.

Thaïs d’Escufon is a former spokesperson for Génération Identitaire, a French identitarian organisation dissolved by the French government for incitement to discrimination and hatred (Le Monde 2021). Her online messaging fuses anti-feminism with white identitarian politics and anti-Muslim sentiment, framing “traditional femininity” as a civilisational defence against immigration and multiculturalism. This narrative blend reflects documented patterns of femonationalism, where selective “pro-women” messaging is used to justify exclusionary or racist political agendas (Farris 2017). D’Escufon exemplifies far-right practices of instrumentalising gender to advance nationalist and anti-migrant mobilisation (Le Monde 2024; ICCT 2023).

Figure 3: Thaïs d’Escufon is affiliated with a French company VK Studio to promote a videopreneur service.

“When making 2000€ a month thanks to video editing becomes a game.”

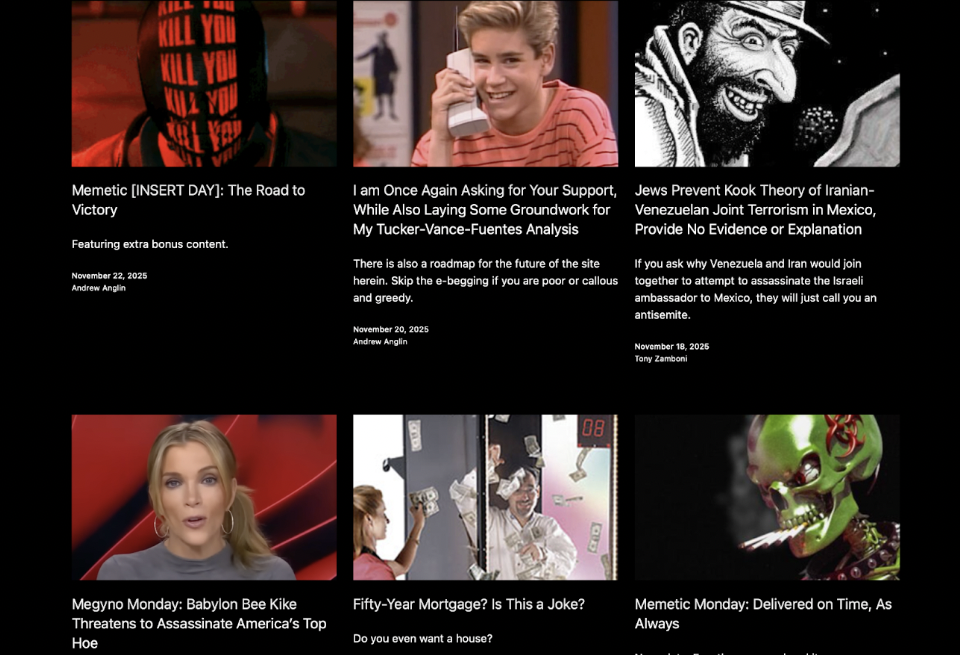

Andrew Anglin, founder of The Daily Stormer, sits at the intersection of explicit antisemitism, white supremacy and violent misogyny. His writing includes calls for harassment of female public figures and rhetoric depicting women as inherently deceptive and deserving of domination (SPLC 2024; ADL 2018). Anglin’s orchestrated “troll storms” have led to severe real-world harassment, and he was found liable in civil court for intentional infliction of emotional distress (BBC 2019). His output demonstrates how misogyny amplifies and reinforces broader neo-Nazi mobilisation strategies.

Figure 4: The Daily Stormer blog section.

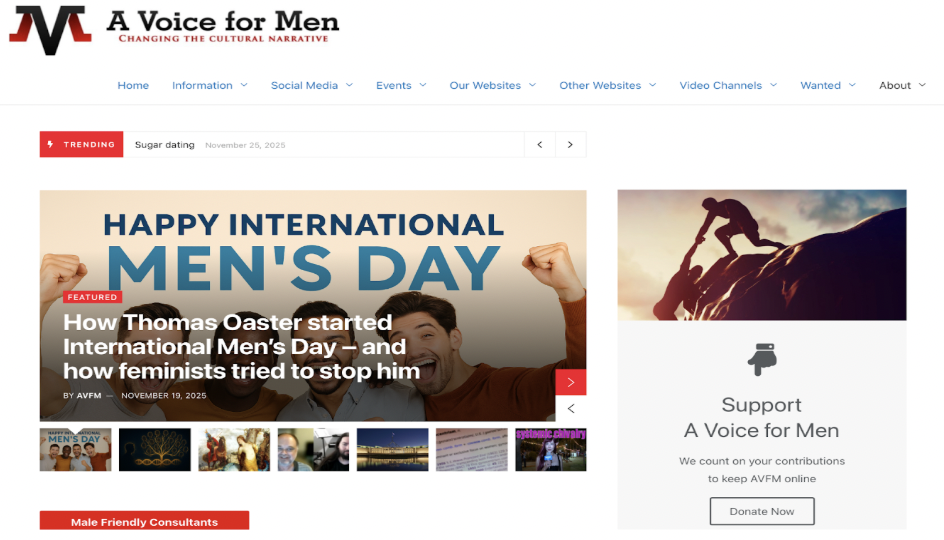

Paul Elam founded A Voice for Men, a male-supremacist hate group promoting claims that feminism oppresses men. AVfM encourages hostility toward women, including campaigns targeting female journalists and academics (SPLC), both on their websites and external platforms. Elam’s narratives emphasise grievance, victimhood and perceived loss of male status, patterns also found in extremist recruitment strategies (ICCT 2023). His content is framed as “men’s rights”, but frequently overlaps with incel, far-right and conspiratorial networks online.

Figure 5: A Voice for Men frontpage.

Nick Fuentes is a far-right Christian nationalist who merges white supremacist ideology, antisemitism, anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric and misogyny. His followers, called “Groypers”, have carried out coordinated online harassment campaigns targeting women, journalists and public figures (SPLC). Fuentes promotes rigid gender hierarchies and rejects women’s political participation. He launched the “Your body, my choice” movement in 2024 (ISD 2024), which included merchandise. Offline, he participated in the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and has been linked to post-2020 election mobilisation efforts, illustrating the strong convergence between gendered hostility and ethnonationalist extremism (ICCT 2023).

Figure 6: Nicholas Fuentes promoting the narrative that men should make decisions about women’s body autonomy.

Andrew Tate is a self-described misogynist whose persona is built around male domination, coercive control and denigration of women. His content circulated widely on TikTok and YouTube, even after platform bans, due to continued support by fans and followers. Andrew Tate and his brother were charged in June 2023 with rape, human trafficking, and forming an organised crime group. In August 2024, Romanian police expanded the investigation to include trafficking minors and money laundering. By May 2025, the UK Crown Prosecution Service brought 21 charges against the brothers, including rape and bodily harm. Research from PBS and SPLC shows a documented rise in misogynistic behaviour among boys in schools linked to Tate’s content, highlighting the real-world impact of highly monetised digital misogyny.

Figure 7: Andrew Tate promotes hate speech towards women and white supremacist narratives.

Adversarial Tactics Employed to Maximise Reach

Adversarial actors have become increasingly sophisticated at exploiting the structure and social dynamics of the online environment to achieve maximum reach and generate high levels of engagement. Instead of merely spreading falsehoods, their strategy involves leveraging platform algorithms, emotional triggers, and conspiracy theories to ensure that their narratives dominate the public discourse. This section will explore the specific tactics employed by these actors.

- Slopaganda

Slopaganda refers to the high-volume dissemination of low-quality content. It is a form of informational attrition in which actors flood discourse channels with incoherent or distorted content to degrade the quality of the information environment. The objective is to produce cognitive exhaustion, creating a distinct “noise” barrier that displaces substantive discourse and renders digital spaces inhospitable to targeted demographics.

- Trolling and Dogpiling

Trolling involves provocative engagement, while dogpiling refers to a coordinated, volumetric attack. Together, these tactics exploit network effects to unleash a disproportionate wave of hostility against a single target or narrative. The goal is to create a psychological atmosphere of siege, leading to self-censorship or withdrawal from the public discourse.

- Engagement Farming

Engagement farming exploits the political economy of social media platforms, specifically algorithms that prioritise emotional responses. Adversarial actors intentionally curate inflammatory, misogynistic content to trigger indignation and counter-speech.

- Memetic Ambiguity

This tactic employs “dog whistles” to encode hate speech within seemingly innocuous imagery. Through plausible deniability, aggressors maintain a dual audience: the content appears benign to platform moderators and the general public, while simultaneously signalling violent intent to an ingroup of radicalised users. This deliberate opacity complicates content moderation efforts and gaslights victims by framing interpretations of threats as paranoia.

- Platform-Hopping

Platform-hopping refers to the strategic use of a multi-platform ecosystem to evade enforcement actions. Harassment campaigns are frequently orchestrated on fringe, unregulated platforms before being executed on mainstream platforms.

- Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour (CIB)

CIB involves mobilising one or more online communities to carry out targeted attacks against groups or individuals, aiming to deplatform the target through harassment or the weaponisation of community moderation tools. Unlike organic backlash, this is a premeditated collective action designed to inflict reputational damage by manipulating social proof systems.

- Irony Poisoning

Irony poisoning is a radicalisation mechanism that desensitises users to extreme ideology through the guise of satire. By framing misogynistic content as “shitposting” or “edgy,” actors create a rhetorical shield: the statement is retrospectively classified as a joke only if it faces social sanction. This recursive irony lowers the threshold for acceptable discourse, gradually normalising extremist views among uninitiated audiences.

- Hate/Rage Baiting

Rage baiting is the engineering of content specifically designed to confirm misogynistic biases and elicit a “fight” response. This involves the fabrication or decontextualization of media to validate internal narratives. Beyond harassment, it also serves as a confirmation loop, solidifying the ingroup’s shared reality and justifying external aggression as a defensive response to manufactured provocations.

- Manufactured Expertise

This tactic involves the appropriation of academic aesthetics to legitimise misogyny, often termed scientific sexism. Actors cherry-pick data, misrepresent evolutionary psychology, and deploy pseudoscientific biological essentialism to frame gender hierarchy as an objective, immutable fact. By mimicking the language of rigour and rationality, actors attempt to bypass content moderation filters and present hate speech as valid intellectual inquiries.

Conclusions and Recommendations

To mitigate this increasingly incendiary ecosystem, stronger and more consistent enforcement of the Digital Services Act (DSA), AI Act, and the European Democracy Shield (EDS) is necessary. Digital platforms need to speed the adoption of DSA’s risk assessment and transparency obligations, in particular those regarding content that promotes misogyny or aids extremist mobilisation (European Parliament, 2025). Platforms that use algorithmic models that amplify or facilitate manipulation, deception, and the exploitation of vulnerabilities need to be audited under the AI Act to prohibit such practices (European Commission, 2025). Additionally, the fight against disinformation and information manipulation through the EDS will be vital to avoid the spread of this ecosystem (European Commission, 2025). EU Directive 2024/1385 on gender-based violence must be swiftly transposed into national law by Member States, ensuring that broadly defined crimes are taken into account (European Parliament, 2024).

Furthermore, platforms should disclose how they intend to improve their accountability and transparency beyond superficial moderation metrics. Platforms must be able to address both blatant illegal content and borderline content that infringes user rights. The vague language surrounding borderline content makes transparency into its accountability more difficult (Rogers, 2025), therefore requiring dedicated mechanisms and constant monitoring to enhance content moderation. Restricting advertising placement, reevaluating algorithmic amplification, and safeguarding targeted demographics could help tackle the financial incentives of harmful content (European Parliament, 2020).

Finally, independent monitoring and research through think tanks and observatories must continue to mitigate radicalisation and gender-based violence. Coordinated action through legislation, civil society, and platforms can potentially disrupt the financial and technical mechanisms that perpetuate misogyny and gender-based violence (European Commission, 2025).

—

Rachele Gilman is an independent expert on FIMI. She was Director of a non-profit, where she led a global remote team of analysts and data scientists, product managers and partners to identify and assess online threats using OSINT, statistics and visualisation. She has extensive experience in detecting and analysing disinformation and information operations from previous roles as a computational disinformation analyst at New Knowledge, an OSINT specialist at Tadaweb, and as an open-source and social media analyst supporting U.S. European Command and the U.S. Department of Defense. She holds a DISARM Analyst Certificate and serves in leadership roles in FIMI-ISAC and the OASIS “Defending Against Deception – Common Data Model” initiative, making her particularly well placed to lead the project’s analytical and methodological work.

Laura Bucher is a researcher and trainer with a strong passion for tackling disinformation and translating complex issues into accessible, engaging content. At Dare to Be Grey, she combines analytical research with effective communication, crafting articles on the online harms ecosystem, creating e-learning materials, running awareness campaigns, and delivering workshops to inform and empower diverse audiences, especially young people, on emotional manipulation and disinformation tactics.

Giampaolo Servida is a research analyst. He graduated with a BSc in Political Science and an MSc in Crisis and Security Management: Cybersecurity Governance. His research focuses on regulatory compliance, disinformation, and cybersecurity. In 2024, he joined Sustainable Cooperation for Peace & Security and is now an active contributor to research and advocacy activities on Cyber Peacebuilding.

Fabio Daniele is an OSINT practitioner and civil society activist, specialised in information disorders. He is a former professional in the IT sector with 10+ years of experience, including the co-founding of a digital startup in E-commerce and Sustainable Tourism, which featured him on the 2019 Forbes Italy 100 Under 30 rank. In 2021, he co-founded Sustainable Cooperation for Peace & Security, a CSO advocating for Peacebuilding and Cyber Peacebuilding efforts in the EuroMED region. Alongside SCPS, he is an independent contributor to various counter-disinformation and counter-radicalisation projects across Europe, providing Intelligence Analysis and Subject Matter Expertise on information manipulation and OSINT.

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.