The Case

Kyle Rittenhouse, the recently-acquitted teen shooter of Kenosha fame, continues to be a cultural and political lightning rod in American politics. He is now a household name, lauded since his acquittal as a “conservative icon”, “hero of the conservative movement”, and the “kind of man you should want to be attracted to”. The trial netted a handful of lukewarm memes, mostly of Kyle crying in the courtroom or the prosecution pointing a rifle over the heads of the jury and audience. With this recent court victory, Rittenhouse created a Twitter account and made the rounds on the media circuit to announce his newest endeavours to sue several big media outlets.

His name sparks interest, rage, and admiration depending on the audience reading or hearing it. He made waves earlier this year as he committed to taking on what he calls defamatory content in news media, something he described as “false narratives” that have led to there being “people out there that want to hurt [him]”. He detailed his legal team’s work to put forward 10+ defamation lawsuits against several key organisations or people who made comments about Rittenhouse, one of which he indicated to be Facebook. Extremely awkwardly, Rittenhouse tweeted that the Depp-Heard verdict was “just fueling” him in his quest. One of the lawyers on Rittenhouse’s team is the same one who sued the Washington Post on behalf of the smirking MAGA hat-wearing kid who stood across from a Native American activist in January 2019. In a November 2021 interview with Tucker Carlson (technically Rittenhouse’s first TV interview), Rittenhouse revealed his woes with one of his former attorneys, Lin Wood, who he described as having “taken advantage” of him. Lin Wood is a Trump ally, QAnon influencer, Atlanta lawyer under investigation for participation in election lawsuits and possible disbarment, and one of the original overseers of Rittenhouse’s now-contested #FightBack bail fund.

In June 2022, Rittenhouse tweeted an announcement that he was launching a new video game to raise funds for his defamation campaign. In the game, the user plays as a cartoon Rittenhouse, shooting “fake news turkeys” with a dart gun. The sole developer of the game attempted a career as a MAGA rapper and has since created a series of right-wing games where players fight “satanic globalist monsters” or adventure through dystopian silicon valley “burning and overrun with hobo zombies”.

Political Memetics: Literature, Methods, and Case Selection

Memes are extremely important in our day and age, offering a crucial platform for political struggle, metapolitics, and the intertwining of comedy, entertainment and politics. Rittenhouse shares memes about himself, referencing his participation in that night of lethal violence. As the US midterms approach, cringe memes are likely to pop up all over the place, created by supporters and partisans alike. The recent racist terror attack on a Buffalo grocery store frequented by Black New Yorkers was accompanied by a shooter’s manifesto referencing the use of memes in recruiting and radicalising other would-be shooters and white nationalists alike. One should be careful taking manifestos at immediate face value, but the signal here is clear regardless: memes and political violence are connected.

The literature on political mimesis is still nascent, growing with the internet and the proliferation of memes and chan sites alike. We seek to add to the literature by offering an analysis of violent content, in-group and out-group construction, and referential image association within the outpouring of support for Kyle Rittenhouse in the wake of his shooting. Our article, now out in Terrorism and Political Violence (TPV), therefore draws from theory and knowledge gleaned from academic sources such as Yuk Hui’s On the Existence of Digital Objects; popular media such as Robert Klemko and Greg Jaffe’s Washington Post narrative essay on the victims of the events in Kenosha, and online crowd-sourced material such as the immensely helpful Know Your Meme. Our TPV article is also based on an initial pilot study we published in GNET’s Insights pages back in 2020 and feeds directly into a second paper we authored in late 2021 comparing the Rittenhouse dataset with two other political meme datasets: neo-Nazis and Hindutva nationalists.

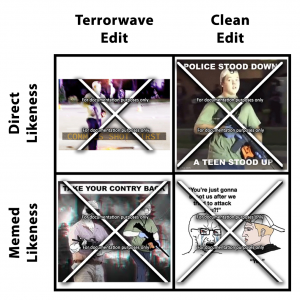

Our methods for TPV involved scraping Twitter and sampling through Facebook, MyMilitia, and meme aggregators in the immediate aftermath of the shootings in Kenosha. This netted us a broad collection of thousands of images, from which we eliminated non-memes (mostly screenshots of news articles or pictures of Rittenhouse with no modification), removed duplicate images, and classified memes according to an ethnographic codebook we developed. Using this codebook, we assessed a dataset of 259 memes for meme characters like Pepes or Soyjaks, various symbols, referential imagery, and icons (often related to violence), and particular meme formats such as macros and ‘terrorwave’ edits (see visual below for a matrix of terrorwave to clean edits and direct likeness of Rittenhouse alongside memed ones – most of which are macros).

We selected pro-Rittenhouse posters for a handful of reasons. The first is that the Kenosha event itself included spectacular and lethal violence. The second is that the August 2020 shootings followed an intense summer of social mobilisation and far-right reaction, acting in some ways as a culmination of violent responses to Black Lives Matter demonstrations. Finally, Rittenhouse captured a ton of clout online in the aftermath of the shooting and continues to be relevant nearly two years after the shooting, meaning his likeness will remain a political artefact online for a while.

Targeting and Violence Permissibility in Rittenhouse Memes

Our study netted rich information about how mainstream right-wing content creators in the US (most of them anonymous) responded to the events in Kenosha. From our assessment and those that followed, we note that memes among political poles and online movements often exhibit non-obvious or clandestine messaging supporting and/or encouraging violence. This isn’t the case for all online communities, even on the right-wing end of the spectrum. For example, in our GNET paper comparing the political messaging of various right-wing groups, an examination of sampled memes among India’s Hindu nationalist movement shows a lower degree of memes supporting violence against their perceived enemies. Instead, creators attempt to paint Indian Muslims as a danger to Hindus. In all cases, whether supporting violence against out-groups or creating narratives focused on victimhood resulting from out-group violence, the insinuation in these cases is that the ‘other’ is a danger that must be dealt with.

Within our study of Rittenhouse memes, we found that two notions seem to matter for pro-Rittenhouse meme posters with regards to violence and out-groups: the out-group referenced and the level of support for violence against them.

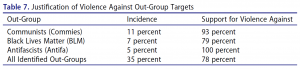

The Rittenhouse meme dataset showed support for the use of violence (63% positive view of violence or otherwise justifying it). However, the acceptability of violence around the memetic detritus of the event’s short-term future rises much higher when a political or cultural target is identified by the creator of the meme. For example, the permissibility of violence within memes rose when the out-group target mentioned was indicated as demonstrators associated with Black Lives Matter (79%), Communists (93%), or Antifascists (100%).

Conclusions

Memetics provide us with an avenue to perform analysis of the memes that are playing an increasingly discursive role and serving as a common form of political communication around the world. Memes function as an easy tool to appeal to political in-groups and concisely spread their message to others, sometimes in an entertaining format. From chan-based message boards to governments at war, memes now occupy all levels of discourse. The methodology used for the Rittenhouse case can be applied to analyse the memes of any discourse. Indeed, memes are increasingly becoming normalised as a standard tool of messaging, even those who use them for ‘shitposting’.

Despite the anti-social behaviour associated with problematic or otherwise violent memes, posting them does not necessarily indicate that the user will engage in violence themselves. We encourage policymakers not to use memes or shitposting as a predictor of violence on their own – many times these behaviours are linked to community-seeking activities online. However, these artefacts serve as a worrying indicator of the psychological and social normalisation of bodily harm and violence against perceived cultural and political opponents–a notion that was particularly true with the Rittenhouse case. Much of the sourcing of our study drew from militia members and right-wing Second Amendment enthusiasts, who remained highly influential over the online metanarrative.

As an indication of how normalised violence and harm was to the community creating and consuming pro-Rittenhouse memes, we found that a significant proportion of the Rittenhouse dataset directly depicted gore or fresh corpses alongside cartoonish meme characters as posters made fun of the recently deceased or maimed (see, for example, author-edited images from the dataset below).

Some of this permissibility of harm (lethal or maiming) is, of course, not unique to Rittenhouse supporters or the American right-wing, and may serve a litany of other purposes according to the literature. Gore, shock, violence, and death for desensitisation, virality, and deliberate trauma response are well explored by other authors assessing neo-Nazis or ISIS affiliates, for example.

Far from disappearing from the public eye, Rittenhouse has seemingly embraced his status as a hero of the conservative movement and as a memetic figurehead. In addition to the media appearances and video game launch we detail in our introduction, we note that Rittenhouse now retweets and amplifies memes of himself created by his supporters. Memes are, of course, not niche internet objects shared by tech-savvy users, but now are as normal and easily reproducible as many other aspects of politics or culture. We have observed a growing ‘memeification of politics’ over the last decade, especially around visual depictions of violence and domination. This extends beyond the Rittenhouse shooting in Wisconsin and is exemplified by the coalescence of memes and lethal violence which can be observed ever more frequently in the US.