Video games are extremely popular, with a market worth over $175 billion per year and at least 3 billion players worldwide. High-speed Internet has also made multiplayer gaming a social activity, facilitating the growth of a gamer subculture and identity, supplemented by online forums and offline meetups, leading to a growing community around this hobby.

Today speculation is rife that many of these video gaming communities are vulnerable to extremist and terrorist groups. Researchers and practitioners are concerned that video gaming forums and games are used as recruitment tools, and that extremist and terrorist groups are producing their own video games, serving as effective propaganda to an overwhelmingly young audience.

Due to this interest, there is a growing literature on video games, terrorism, and extremism. This Insight looks to provide an overview of this literature and the associated literature on Internet masculinities. The article is split into two parts, looking first at online video gaming communities, and then at video games themselves. While recent research has also been interested in gamification, this is beyond the scope of this review. Additionally, this review looks only at online gaming communities. Further work is needed to link the offline and online gaming communities. This too is beyond the scope of this review.

Online Gaming Communities

While today video games are widely accepted, this has not always been the case. In the 1990’s debates raged as to whether video games can cause violence, drawing a connection between school shootings and violent video games after the Columbine shooters were found to be fans of the first person shooter (FPS) Doom. Subsequent research has found little support for this relationship. Nonetheless, many continued to see gaming as an anti-social, insular, and deviant activity, associated with socially misfit nerd subcultures.

Today gaming has largely escaped this association with deviance. However, many gaming communities are not inclusive places. Typically, gaming is associated with young, white, heterosexual males. While it is increasingly recognised that other demographics enjoy playing video games, gamer communities are not welcoming to non-white, queer, and non-male persons. Research in 2016 noted that while “[w]omen and men play video games in approximately equal numbers … video gaming is still strongly associated with men. A common justification for this stereotype is that, although women might play games, they should not be considered “true” or “hard-core” gamers because they play more casually and less skilfully compared to their male counterparts.”

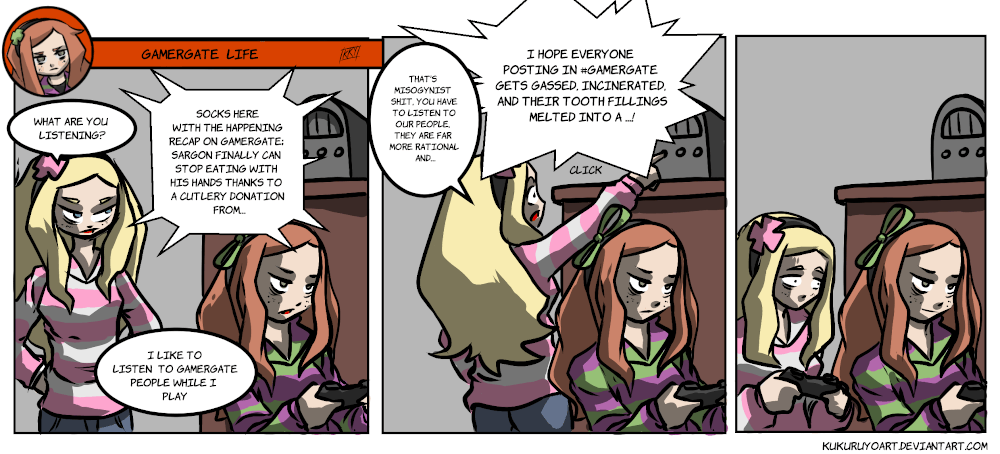

For many this is truth is exemplified by the GamerGate campaign. In 2014 aspects of the gaming community mobilised obstinately to protect ethics in video game journalism, engaging in targeted harassment, doxing, and threatening female game developers and critics across multiple online platforms and forums. Chess and Shaw argue that GamerGate was the moment when “masculine gaming culture became aware of and began responding to feminist game scholars,” and that it was this outsider threat that sparked the anti-feminist mobilisation. Others have noted how GamerGate as an incident highlighted the latent hostility to feminism and femininity within the gaming community. That several far-right personalities became attached to this movement and became popular in video game communities further problematised this moment. Some authors have linked this with an ‘algorithmic radicalisation’ and a wider rise in the reactionary masculinities of the ‘Manosphere’, and especially with a ‘Beta masculinity’ which celebrates misogyny, racism, and ‘niche’ pornography in the face of white disenfranchisement.

A cartoon depicting the GamerGate campaign’s unofficial mascot, Vivian (R), listening to Sargon of Akkad while playing video games

GamerGate highlighted the tendency towards reactionary cultures in gaming communities, especially towards race, gender equality and feminism. This reactive nature of gaming communities is one reason why some consider gamers to be a community vulnerable to extremism. Some argue that these communities are exposed to harmful stereotypes about minorities via the video games they consume. The prevalence of ironic language and racist “griefing” also makes these spaces unwelcome for non-white, female, and queer persons, who are likely to be labelled as outsiders if they call it out. The ADL found that this language was so prevalent that “[23%] of players are exposed to discussions about white supremacist ideology and [9%] are exposed to discussions about Holocaust denial.” A further study found that Steam, one of the most popular gaming platforms, had several groups which were explicitly pro-Nazi and white supremacist.

However, video gaming communities are not homogenous. Diverse gaming subcultures and identities have developed including feminist gaming, LGBTQ+, and communities that follow niche interests like retro gaming. Additionally, whether extremists are generally present, influential, and politically active in mainstream gamer-identified video games communities has yet to be established. An investigation by Bellingcat into leaked Discord chats revealed that some white nationalists were radicalised by their involvement in GamerGate and subsequent exposure to the right-wing personalities that coalesced around the campaign. However, while the GamerGate campaign is a key example that highlights such activism in relation to misogyny and male supremacy, there remains a lack of evidence that video game communities as a whole are uniquely vulnerable.

However, the anti-progressive nature of gamer identity should raise some concerns. For instance, right-wing extremist propaganda can spread often unhindered on the web if not challenged. Learning and using the slang, symbols and practices of these extremist movements also eases entry. Further, studies have shown that online interaction in homogeneous groups can strengthen extremist opinions and that this can lead to negative opinions about out-groups. Thus, the challenge faced by those who do not meet the white-hetero-male requirement to be seen as a gamer can be seen as part of a wider problem of a hostile and strengthening anti-progressive identity. In this context, the speculation that gamers are vulnerable to extremism makes sense, in particular with relation to right-wing extremism. However, more research is needed. Indeed, this fits in with a wider research agenda on extremism in online forums.

Video Games

It is not just gamers and game players that are of interest to the study of extremism and terrorism. Video games themselves are a communicative medium that can carry messages, and thus have been investigated as both tools for recruitment, socialisation, and ideological transmission. Due to the popularity of video games, references to gaming culture and practices have slipped into other social and mainstream media outlets to reach out to a younger audience. Indeed, Islamic State (IS) has been notable in producing videos which ape the video game Call of Duty as a ‘dog whistle’ to the video gaming community.

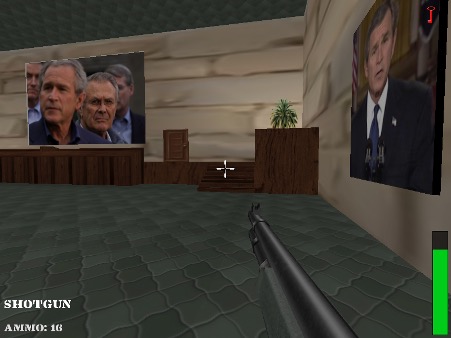

While there has been increased interest from PVE practitioners, the use of video games in this way is not new. Political messaging in video games is common, and right-wing extremists have long been publishing video games with an ideological message. The political use of gaming is used across the ideological spectrum, too; Hezbollah famously released a series of video games upending the narratives of the War on Terror, tasking the player to undertake bombing missions in Israel.

Hunting for George Bush in the Global Islamic Media Front’s “Quest for Bush” (2006)

These games allow groups to simulate a spectacular, propagandistic attacks. Players can imagine themselves as active participants, increasing their identification with the organisation. The game environment can also be used to simulate the unfairness of material conditions on the ground. The games framework and rulesets – what Bogost calls procedural rhetoric – can be used to force the player into certain positions and thus encourage different ways of thinking. Players can for instance experience events from multiple angles, experiencing different perspectives on the same event. Individuals and organisations do not have to develop such games from scratch but are able to modify, or ‘mod’, existing games so they present the messages and play in the way that the modifier wishes.

The latter points highlight the complexity of studying ideological messages within games. While procedural rhetoric is usually recognised by players, it does not necessarily impact them in the way the designers intended. One study looks at how right-wing extremists created their own, racist, understanding of the video game The Elder Scrolls IV: Skyrim. Although the game contained no explicit racist messaging, members of the Stormfront white-nationalist forum reinterpreted the game as white nationalist, identifying with one of the games ‘races’, the Nords, and identifying another, the Elves, as Jews. Thus, while games can be coded to explicitly include certain messages through stories, gameplay and character, the interactive nature of games means that the player can creatively manipulate how they experience it. This creative element of games allows players to play as they see fit, and craft their own messages. This poses a challenge for understanding ideological transmission in video games. We, therefore, should not simply look to just ‘read’ the ideological messages within games, but should also look at how those games interact with the players and the wider gaming community.

This question becomes more fraught as we consider interactivity in relation to multiplayer games. Within gaming environments where multiple people can play together aspects such as in-game chat, environmental sprays or tags, or player actions, can all function as ways that players can collectively make meaning, interact, and police identities. For instance, the misogynistic nature of gaming communities means that women in online multiplayer games are likely to experience discrimination, sexual harassment, or gendered abuse and people of colour are likely to experience racist abuse. This can be experienced in the in-game chat, or by players engaging in virtual physical abuse of other players. This can occur through things such as crowding out other players, purposefully killing unwanted teammates, or abusing the virtual corpses of players to humiliate them. While some of these prejudicial behaviours are because of discriminatory beliefs, some players simply do it for amusement or because it is considered part of the gamer culture.

A Nazi flag custom spray in a reskinned Counter-Strike

This complexity brings us back around to the study of video game communities and the relationship these communities have with publishers. The anti-progressive tendencies of gamers have been located by some researchers within mainstream video games themselves. Many mainstream video games are filled with ideologies of hedonism, cynical realism and escapist defeatism. This synergizes with the ‘red pill’ ideas of the Manosphere – the corner of the Internet associated with highly misogynistic and patriarchal attitudes. Daniels and Lalone for instance compare the games made by and for the far-right with mainstream games, arguing that popular games like Grand Theft Auto V portray race in ways that lend themselves to racist interpretations. This then leads to the exclusion of minorities from gamer culture. Indeed, the sexism inherent in gaming communities can also be found reflected in mainstream game design.

Screen from Feminist Frequency’s “Tropes vs. Women in Video Games” series, dealing with sexism in video games

However, there is limited evidence on the purpose and effect of video games, both extremist and mainstream, on player attitudes. Additionally, a recent study noted that extremists tended not to use video games to recruit, but rather to socialise with one another. More evidence is needed on not just the ideological content of extremist games, but also on how players creatively experience them. More research is also needed on whether mainstream games contribute to anti-progressive attitudes in gamer communities and whether this, in turn, feeds extremist vulnerability. Further, multiplayer gaming has been well investigated as an environment where sexism and racism are rife, but few studies have looked at the fomenting of wider extremist attitudes in this realm.

Conclusion

While we know a lot about video games and video game communities, we know relatively little about extremism within these areas. Research has highlighted the reactionary and racist potential in video game communities, but we are yet to establish whether these communities are uniquely vulnerable to extremism. Likewise, research has shown that video games can harbour extremist ideologies and that those extremist organisations do develop video games for ideological messaging and in-group socializing. However, the interactive nature of gaming means that it is unlikely that such messages are simply passively received. Rather, players can creatively imagine their meaning through play. Foremost, this review highlights the need for more primary research into games and gaming communities; this review serves not only as an introduction to the subject but also as an introduction to a wider series on exploring video games, video game communities and extremism through primary data.