The 7 November 2025 attack at Sekolah Menengah Atas Negeri 72 (SMAN 72) in North Jakarta represents a troubling manifestation of transnational extremist subcultures taking root in Southeast Asia. Since 2020, the region has witnessed a troubling trend of youth-perpetrated violence that defies conventional extremist categorisation. In October 2023, a then-14-year-old teenager opened fire at the Siam Paragon mall in Bangkok with a Glock 19, killing three people. Back then, Thai authorities had treated the incident as a mental health issue, but his tactical gear, modelled on American active shooters, hinted at something more ominous.

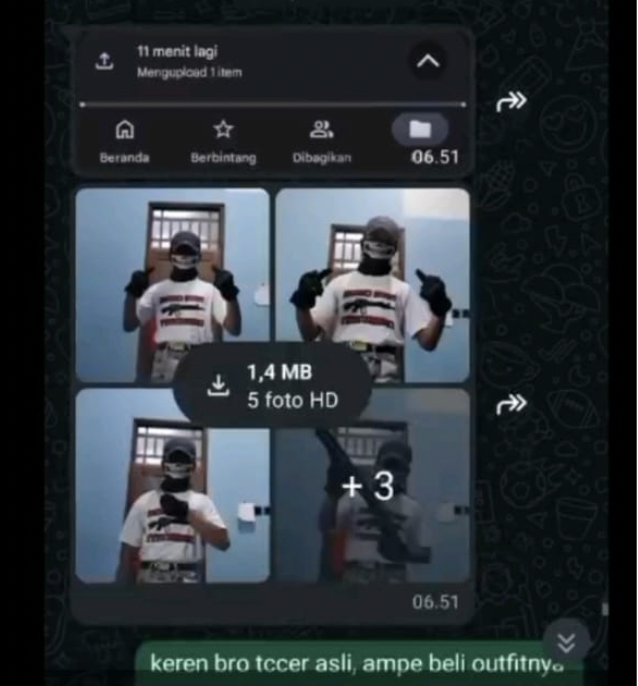

Figure 1: Social media selfie of the Siam Paragon shooter, modelling his tactical “fit” two months before the October 2023 attack. The account has since been taken down by the platform. (Source: Discord).

Meanwhile, in Singapore, the Internal Security Department have successfully disrupted several youth attack plots, detaining 12 teenagers influenced by violent online content. Four of them espoused far-right extremism, with two of them particularly inspired by Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator responsible for the 2019 Christchurch Mosque attack. One of them, Nick Lee Xing Qiu, even tattooed the Sonnenrad on his elbow. Separately, two weeks before the SMAN 72 attack, a 14-year-old Malaysian teenager, influenced by the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre, attacked his schoolmates with a combat knife and fatally stabbed a senior female student, with whom he had developed an obsessive parasocial relationship. The two had never interacted prior to the attack.

Superficially, these incidents bear little resemblance to one another in terms of attack modality, motivation, target selection and geographic context. What binds them together, however, is not ideological alignment, but operational characteristics: systematic premeditation, deliberate planning, aesthetic curation, and a pronounced desire for notoriety derived from committing mass violence. This Insight analyses the emergence of memetic violence in Southeast Asia, a phenomenon whereby perpetrators appropriate the aesthetics and methodologies of notorious Western attackers through online exposure rather than ideological commitment, and to understand how these attacks manifest through digital platforms, collective glorification of violence, and e-commerce accessibility.

Why Now? The Shift from Organised to Memetic Violence

For years, security analysts anticipated ‘lone-wolf’-style jihadist attacks to take place in the region. Historically, terrorism and insurgency-related violence in the region involved two or more individuals linked to organised groups and networks such as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), the Islamic State (IS), and Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD). The 2002 Bali Bombing established a blueprint for subsequent coordinated attacks. However, as the region’s security apparatus grew more sophisticated and police intelligence improved, planned attacks were increasingly thwarted before execution. Consequently, when the Islamic State began promoting a decentralised approach through its propaganda around 2014 to sustain operational tempo, double-tap strikes became notably frequent to maximise casualties.

The 2024 Ulu Tiram incident, where a young man attacked a small police station outpost in Johor, Malaysia, while brandishing an IS banner, initially appeared to conform to these “lone wolf” expectations. In reality, however, the case involved extensive training, encouragement, and ultimately deployment by his own fanatical father, who himself was a former JI member. Regardless of ideology or intention, the attack continued to underscore a persistent and familiar pattern: group dynamics, hierarchical structures, mentorship, and organisational cohesion that remain deeply embedded in the region’s history of kinetic action.

Crucially, this demonstrated that successful attacks require team coordination or close-knit collaboration within the region’s robust security environment. As Jacob Shapiro prominently noted, groups can facilitate attacks but face a critical trade-off: operational support versus detection risks. The Ulu Tiram case proved an exception because the perpetrators operated as a family unit.

The Memetic Violence Framework

This calculus, however, has been profoundly disrupted by the emergence of memetic violence, which operates on an entirely different logic. Generational shifts in access to information and technology have produced a cohort of ‘extremely online‘ youth, a condition intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic’s enforced quarantine during formative adolescent years. Within this digital immersion, young people are continuously exposed to algorithmically amplified content, which may involve rage bait, hyper-violence and macabre that bombards them with visceral imagery and inflammatory messaging. Digital platforms collapse geographic boundaries, consequently allowing individuals to access and internalise forms of violence that have no historical precedent in their own societies. One prominent online space facilitating this is True Crime communities (TCCs).

Figure 2: Screenshot of a conversation regarding an unidentified individual modelling tactical far-right militia attire. The reply in Indonesian reads, “Cool, bro is the original TCC that he even bought the outfit,” indicating recognition and validation within True Crime Community subcultures. (Source: TikTok).

TCC comprise disparate internet fandoms glorifying the macabre, from high-profile mass killers to graphic depictions of death. These attackers likely inhabited similar thematic spaces across different platforms rather than belonging to the same community. But to reduce these youths to “white supremacist wannabes” is an oversimplification.

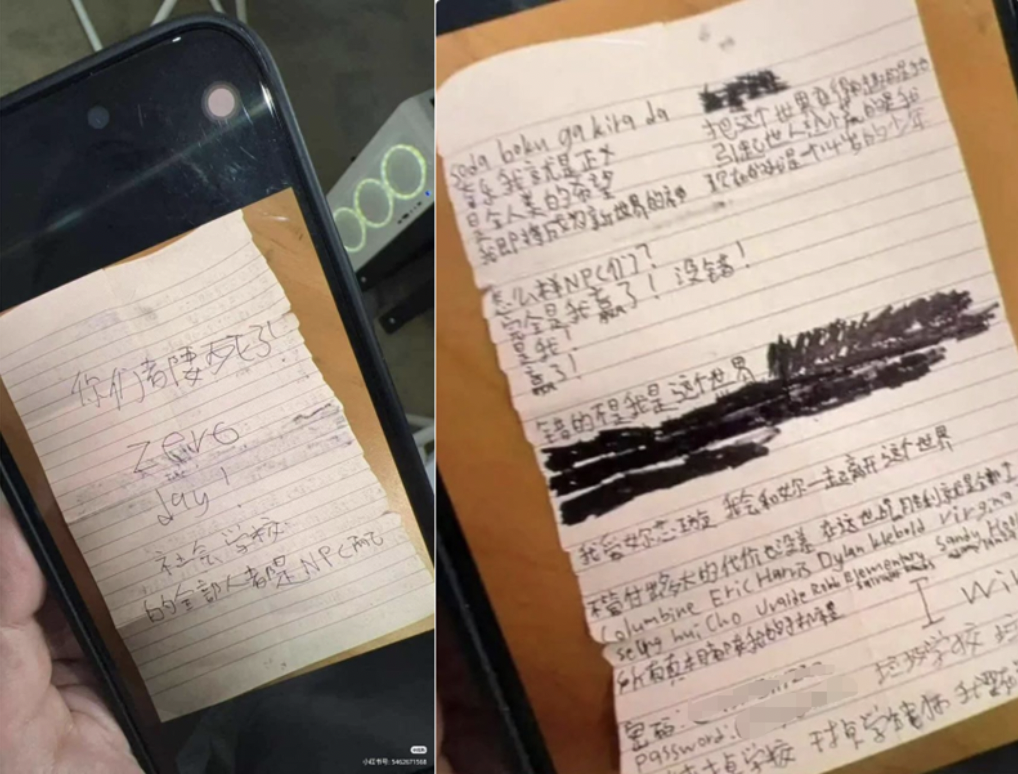

The young attackers previously mentioned in this Insight are not ideologically committed in any coherent sense. Rather, their anger and grievances manifest through emulating violent men who made them feel empowered. The SMAN 72 attacker allegedly suffered persistent bullying, while the Bandar Utama school and Siam Paragon mall attackers experienced loneliness and rage. The Bandar Utama school attacker struggled academically despite his intelligence due to language barriers. Social exclusion emerges as a consistent pattern across cases. For these youths, the framework of dominance they understood was rooted in monstrosity, which they wish to emulate. Both the Malaysian attacker and the Indonesian perpetrator left behind manifestos in the style of Western mass killers: one listed school shooters in a handwritten note, the other scrawled white supremacist names on his airsoft gun.

Aesthetic curation binds these elements together. Yet, there are practical challenges to this. When seeking to replicate infamous killers’ attire, sourcing authentic items locally often yields poor imitations. Furthermore, teenagers across Southeast Asia lack US-style firearm access due to strict gun ownership policies. The proliferation of e-commerce platforms, however, has dramatically transformed the landscape.

Figure 3: Left: Eric Harris wore a “Natural Selection” t-shirt during the 1999 Columbine massacre, as shown in this Zero Hour dramatisation. Right: Another teenager cosplaying as the SMAN 72 attacker at a Jakarta event shortly after the attack, replicating Harris’s outfit with an airsoft rifle inscribed with white supremacist names. Both display the white supremacist “OK” hand gesture.”

Various reports, from Singapore’s ISD arrests to the latest Indonesian attack, highlighted key similarities: these teenage perpetrators sourced their tactical “fit” and equipment through online shopping. The Bandar Utama stabbing attacker evaded parental surveillance by ordering his combat knife to a collection point instead of his home address. Similarly, the SMAN 72 attacker purchased tactical webbing and bomb-making materials online, while the Bangkok shooter acquired both his weapon and ammunition through digital marketplaces.

Figure 4: Tactical vest purchased online by a then-16-year-old Singaporean detained in 2020 for planning a Christchurch-style attack. The listed machete on Carousell was his intended purchase. (Source: Singapore ISD).

E-commerce platforms such as Lazada, Shopee, and Carousell provide unprecedented access to speciality goods, allowing buyers to procure specialist items or commission custom fabrications from vendors specialising in bespoke production. Lee, for example, had his Sonnenrad T-shirt custom-made through an online seller. Similarly, the other Singaporean Christchurch attack aspirant also purchased his tactical vest online.

Ideological Displacement and Performance

The SMAN 72 attacker’s profile might exemplify a disconnect: a Muslim teenager attacking Muslims whilst emulating Western far-right extremism defies conventional analysis. Some questioned whether this constituted a school or mosque attack, others claimed non-existent TCC recruiters were preying on children. Yet, both framings fundamentally miss the point. In maritime Southeast Asia, mosques are commonly integrated into school infrastructure, making them both religious and educational sites. However, fixating on this distinction overlooks the actual driver: the perpetrator’s deliberate choice to attack his own school indicates grievances related to that environment, paralleling the Bandar Utama school attacker in Malaysia, who experienced social marginalisation by his schoolmates.

Figure 5: Citational practices in memetic violence. Top: Handwritten note by the Bandar Utama attacker listing US school shooters and locations as inspiration, along with ‘Zero Day’, a fictional found footage film based on Columbine. He described his schoolmates and teachers as “NPCs” (non-playable characters), dehumanising language paralleling the 2024 Eskişehir stabbing in Turkey, where the attacker similarly referred to victims as “NPCs” in his own manifesto. Bottom: The SMAN 72 attacker’s airsoft DCobra is inscribed with the names of known white supremacists, just like Solomon Henderson did in his attack.

What requires explanation is not the attacker’s choice of target, but the aesthetic framework through which he expressed his fury. The SMAN 72 perpetrator, reportedly Muslim by registry, outright rejected his religious identity and instead adopted Western far-right extremist aesthetics. This self-hatred and identification with ideologies that would target people like him reflects the profound psychological impact of pervasive Islamophobia and white supremacist racism shaped by the two-decade Global War on Terror, compounded by the rising manosphere phenomenon. This self-loathing paralleled the Nashville school shooting, where the suspect, Solomon Henderson, reportedly exhibited a similar trait. In these cases, perpetrators have internalised racial hierarchies that inform their understanding of power and masculine identity. What we are witnessing is performance rather than ideology, aesthetics divorced from coherent belief systems, weaponised to articulate antipathy.

This pattern of acute animosity erupting into explosive violence is not entirely new to the region. The Malay concept of ‘amok’ historically described men who, after profound shame or loss, engaged in killing sprees. What we see today represents an evolution: perpetrators copy Western killers’ aesthetics and seek validation and audience from online communities rather than acting in isolated rage. Western active shooters offer a framework of masculine dominance that these youths find compelling. The underlying dynamic remains familiar: resentment, social exclusion, and perceived powerlessness channelled into spectacular violence.

Masculinity, Powerlessness, and Hyperviolence

These youth perpetrators also share distinctive characteristics across geographic and cultural boundaries. The typical perpetrator is likely a male teenager between 13 and 19, characterised by loneliness, personal grievances, extensive online immersion, and adolescent angst intensified by digital culture.

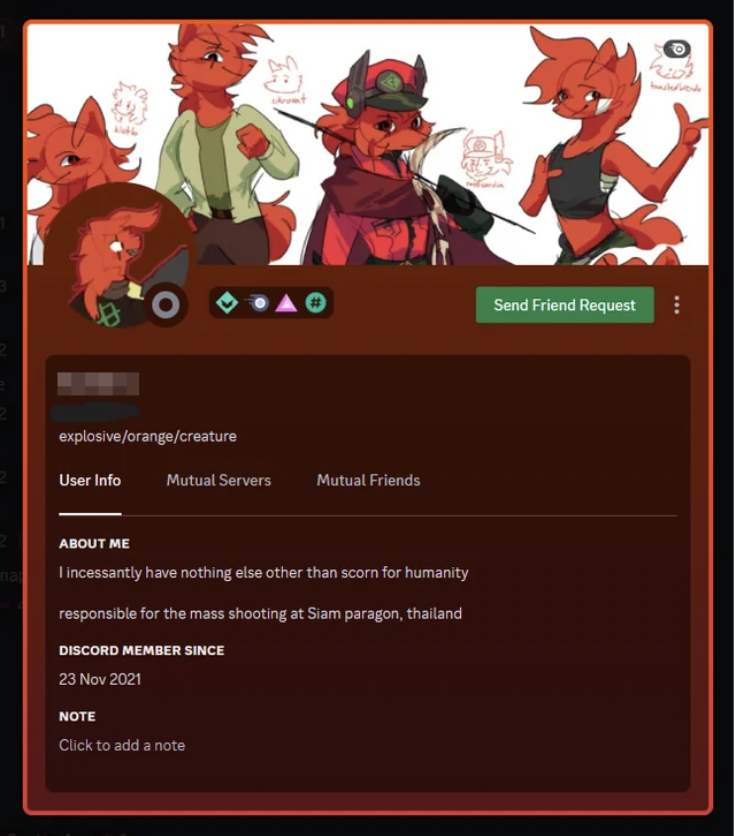

Figure 6: Alleged Discord bio of the Siam Paragon mall attacker, updated before the attack, claiming responsibility for the impending Siam Paragon shooting. His declaration of “nothing else other than scorn for humanity” indicates nihilistic motivations. The platform removed the account. (Source: Discord).

Critically, these attacks serve to compensate for feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness through the construction of masculine identity via hyperviolence. Involvement in the TCC subcultures, which glorify mass murder and fixate on gore, shapes how these young men understand control, agency, and significance. Sustained exposure to graphic violence and gore erodes empathy, desensitising these young men to human suffering. This dehumanisation manifests clearly in their own words. The Siam Paragon mall shooter expressed contempt for humanity itself (see Figure 5), while the Bandar Utama school attacker bitterly referred to his schoolmates as “NPCs” (non-playable characters) in his manifesto, reducing them to background characters devoid of value. The tactical gear, manifestos, and citations of previous attackers are not merely aesthetic choices but central to constructing a sense of formidable masculine agency. In the absence of positive social bonds and constructive outlets, hyperviolence becomes both a pathway to meaning and a framework for understanding what it means to be capable as a man. Whilst millions of teenagers around the world experience bullying and anger, potential attackers differ through sustained exposure to extremist content and communities that validate violent responses.

Recognising the Warning Signs

While some perpetrators, such as Siam Paragon mall shooter and Bandar Utama school attacker, exhibit elements consistent with nihilistic beliefs, the majority demonstrate primarily performative emulation with minimal ideological coherence. This is why memetic violence, rather than Nihilistic Violent Extremism, provides a more accurate framework for characterising these attacks, because it captures copycat behaviour rather than ideological commitment.

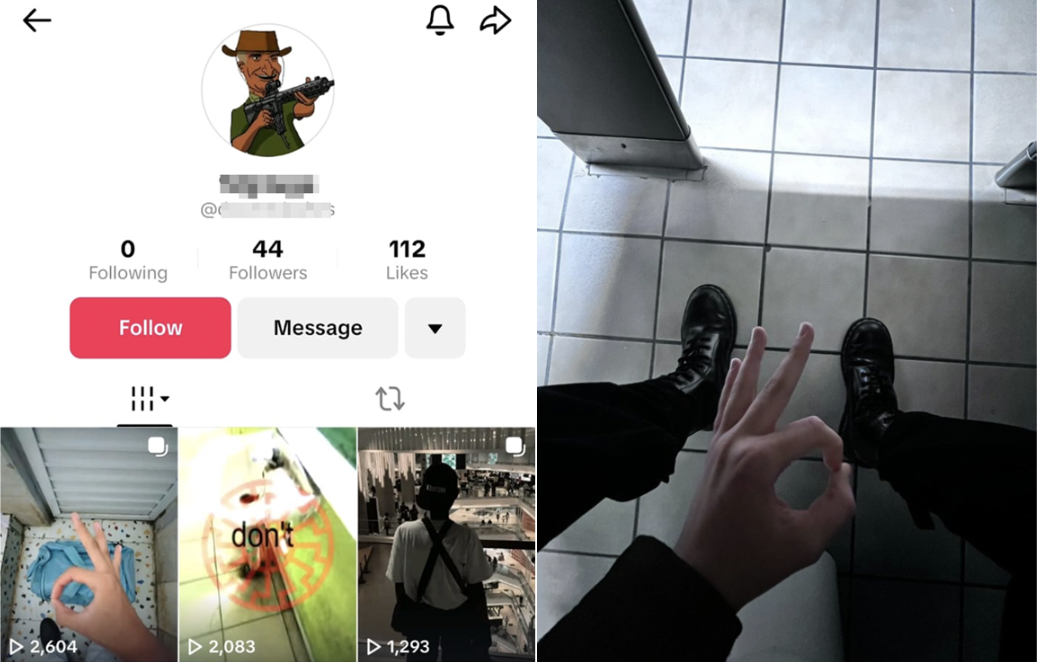

Figure 7: Left: The SMAN 72 attacker’s TikTok account displaying white supremacist symbolism and gestures whilst dressed to emulate Columbine shooter Eric Harris. The hand gesture references Natalie “Samantha” Rupnow, who carried out a school shooting in Wisconsin in December 2024 and flashed the same sign prior to her attack (Right). His profile photo features a meme character associated with an Australian far-right group, the same imagery used by Christchurch shooter Brenton Tarrant on his social media accounts. The account has since been removed by the platform. (Source: TikTok).

What stands out is the emphasis on emulation over ideology. These teenagers operate as fans on the periphery rather than committed ideologues, consuming content and aspiring to replicate attacks. Online spaces foster mutual encouragement, with disaffected youths goading one another towards violence. No recruiters or mentors are necessary. The perpetuation of esoteric symbolism reinforces their sense of participating in a broader movement and arcane in-group knowledge, despite the absence of any organisational structure. The very movements they idolise would likely reject them as outsiders based on ethnicity or skin colour, but this does nothing to diminish their sense of belonging to the broader violent extremist subculture they seek to emulate.

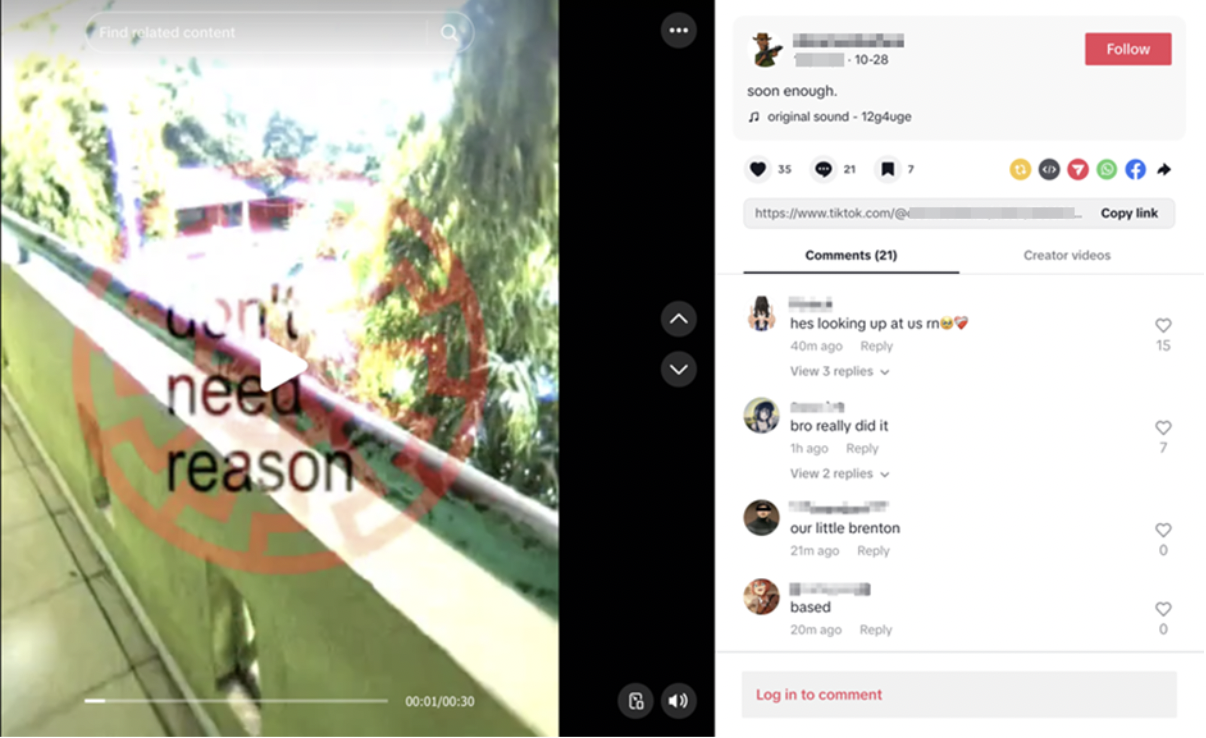

Most perpetrators also undergo a “peacocking” phase before attacks. The SMAN 72 attacker posted extremist TikTok videos (figures 7 & 8). The Siam Paragon mall shooter posted tactical selfies and shooting range videos. These examples show how the perpetrators seek validation from their online peers who understand the references. This can offer a crucial intervention window.

Figure 8: The perpetrator allegedly posted this video on his TikTok before his attack, with the black sun symbol overlay. After the attack, the post drew celebratory comments from other boys, illustrating how peer validation within these communities reinforces the drive to act.

The Challenge for Southeast Asia and Moving Forward

Countries in the region maintain closed information environments with limited transparency around security incidents, potentially hindering shared understanding and the development of best practices. Perhaps most critically, unless law enforcement agencies keep abreast of current research on NVE and memetic violence, such incidents will likely be misunderstood or mischaracterised.

Traditional counterterrorism and PCVE frameworks designed for organisational extremism prove inadequate for addressing decentralised, aesthetically-driven violence. These attack patterns emerge not from ideology or organisation, but from aesthetic appropriation, collective adulation of mass killers and white supremacists, and e-commerce accessibility. Effective prevention requires enhanced digital literacy, mental health assistance, enhanced community support structures, and positive pathways for youth beyond these harmful subcultures.

But most importantly, tech companies must address the infrastructure enabling memetic violence. Social media platforms should review algorithmic recommendation systems that funnel users from TCC content into violent subcultures. While content moderation remains heavily focused on “Islamist” content, far-right values, hyperviolence and gore continue to proliferate unchecked. Platforms should also try to detect “peacocking phase” behaviours, such as posting content featuring tactical gear or firearms, but this should require cumulative behavioural assessment conducted in partnership with educational institutions and authorities rather than relying on single indicators.

E-commerce platforms also have a role to play. They should improve existing safeguards for youth purchases of tactical equipment and weaponry by introducing age verification requirements at collection points similar to those for cigarettes or alcohol. Most critically, social media companies must remove algorithmic incentives that reward rage bait and hateful content. The commodification of misogyny and hegemonic masculinity content within manosphere communities creates pathways into violent subcultures, and platforms must address how their engagement-driven business models amplify this content to vulnerable youth audiences.

—

Munira Mustaffa is a security practitioner based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She is the founder and Executive Director of Chasseur Group, where she serves as principal consultant specialising in critical security challenges. She is also a Senior Fellow at Verve Research.

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.