In the morning on 16 December 2025, local police were called to a school in Gorki-2, a 30 minute-drive West of Moscow city centre. A 15-year-old student – named in reporting as Timofey K. – stabbed a 10 -year-old student to death and further injured a security guard at the school. In the hours following, it was revealed that the attacker had posted a manifesto on a Telegram group chat and shared it with classmates. Tracing references from Russian social media posts and local media reporting, the Repository of Extremist Aligned Documents (READ) was able to locate the manifesto for analysis and make it available to platform users. Exhibiting a mixture of Islamophobia, Nihilistic Violent Extremism (NVE) and white supremacist Great Replacement rhetoric inspired by previous attacks, the attack stands as an example of the persistence of previous attackers’ narratives as well as their mixture with the increasingly recognised NVE landscape.

According to Telegram messages, the manifesto was posted to two group chats: one used by some of his classmates and another in a Russian-language group for the video game GoreBox. The game’s listing page on Steam describes it as “a chaotic physics-driven sandbox where creativity meets destruction,” and contains a mature content tag for “realistic blood pooling and dismemberment [and] ragdolls which react to wounds.” Like other shooter games in this style, it features blocky graphics and the ability to create custom maps or mods, which can be shared with other users. It is important to highlight that members of the Telegram chat for this game – many of them appearing to also be children – were very vocal in their rejection of the attack, posting both official chat-wide and more vulgar personal condemnations of the terrorist. Some worried that the negative attention would affect the game, for example, that Russian security services could use the attack as a pretext to ban the game.

In light of meta-analyses that “do not appear to support substantive long-term links between aggressive game content and youth aggression”, we should view the crucial digital element of this attack’s context through the attacker’s behaviours in the group chat and his use of the gaming space, rather than attaching them to the game itself. Gaming in this case served as a space for play and soft engagement with ideological violence before an attack, in a low-stakes and rehearsed expression of identity. User-generated content that alters the games with “harmful design” or engages in extremist visions are seen across the spectrum of gaming, from AAA productions to indie games. Given the difficulty of regulating mods or maps that are not hosted on major gaming platforms, understanding the ideological dynamics may be more useful, in this case, than promoting an outright ban on certain games or features. As the UK age-gating of adult content has shown, increasing friction to access without addressing underlying ideological, social and personal drives can inadvertently cause those seeking violent or censored content towards other dangers.

With these considerations in mind, this insight discusses the online activity and manifesto of the Moscow Oblast School attacker to unpack the motivations and ideological drivers behind the event. It traces his pre-attack expressions of ideology, the references and inspirations behind his manifesto, and closes with a brief look at post-attack reactions from different communities.

Ideological Motivations

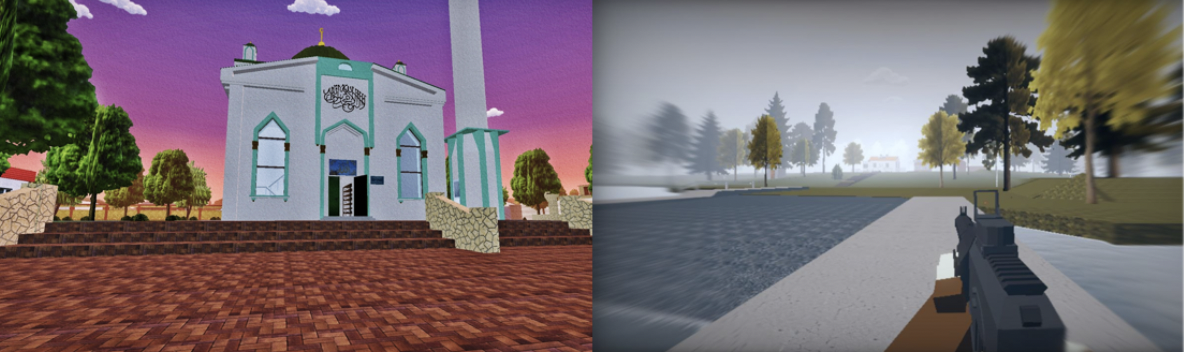

The map-making function on prominent video games has been used both to practice attacks or to glorify and recreate past ones, both by Islamic and extreme-right users. Notably, the Moscow perpetrator made a number of such recreations; one such map is of a Mosque. Online conversations in the six months leading up to the attack reveal a persistent belief in the evil and destructive nature of both Islam and Islamism, an equivalence the attacker draws explicitly in the manifesto, where he justified violence against Muslims as part of a struggle for Russia’s Christian, European soul. That the attacker expressed his views within the social dynamics of a publicly visible but low-friction, gaming-oriented chat populated by others around his age points to the potential value in proportionate, behaviour-led safeguarding that is sensitive to escalation signals without treating gaming communities as inherently suspect.

Figure 1: Two maps made by the perpetrator (Left: Mosque, right: Utoya Island).

Violence was further evoked by the attacker as a justified response to attacks by jihadist terrorists, potentially evoking the concept of cumulative extremism and made possible by witnessing footage of previous attacks by jihadists. On 22 September 2025, two months before his attack and after posting the Mosque map, Timofey posted “there will be no more [mods/maps] from me.” This belief appears to have shaped the attack itself: in the livestream, the perpetrator moves through the school asking younger students about their nationality. The student he eventually killed was a Tajik, hailing from a nation which is over 95% Muslim. This prompted a response from Tajikistan, calling for justice and for movement against xenophobia in Russia.

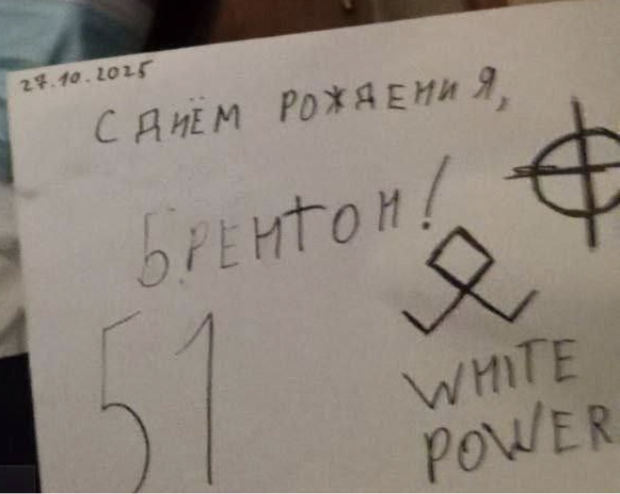

The Islamophobic throughline is also seen in the attacker’s particular affiliation with Brenton Tarrant, who carried out the 2019 Christchurch Mosque attacks and has been celebrated by extreme-right terrorists ever since. The manifesto, as many have done before, cites Tarrant in several places; it discusses his “love” of Christianity for saving Europe during the Crusades, as well as referring to the Great Replacement as both the title of Tarrant’s manifesto and a broader conspiracy theory that white people are being intentionally replaced with non-white immigrants. In the Moscow attacker’s manifesto, sections are divided by topic and titled in ways reminiscent of Tarrant, and his portrayal of immigrants as “invaders” further aligns with the perspective that violence is necessary or even expected.

Figure 2: Cropped image of a sign written by Timofey reading “Happy Birthday, Brenton!”, October 27th, 2025. Pictured are an Othala rune, used by the SS, and a Celtic Cross used by white supremacists.

The text is replete with other extreme-right messaging beyond the Islamophobic focus. Its cover bears a large image of a sonnenrad, 2019 Halle synagogue attacker Stefan Balliet is mentioned, and Nazi propaganda minister Goebbels is quoted. Another map the attacker created for GoreBox is a recreation of the site at Utoya island, Norway (Figure 1), where Anders Breivik carried out his attack “exactly as it was on July 22, 2011”. There is a further indication that the attacker was a fan of Payton Gendron, the 2022 Buffalo shooter, having commented on shared maps emulating the site of this attack. Other American right-wing terrorists like Dylann Roof are mentioned despite differences to the Russian context, a testament to the globalisation of the extreme-right and of copycats in particular.

In the same vein, Timofey includes in his manifesto praise for six non-white attackers who held some degree of extreme-right views and includes instructions on the construction of homemade guns and explosives, with the specific affordance that other underage individuals will have difficulty accessing firearms for sale. This, read in conjunction with calls for others, should be read as an intention for his manifesto to be spread and incite further attacks. However, rather than translate it into English – the lingua franca of such manifestos, as seen with attacks such as Bratislava – the manifesto was posted to a relatively niche Telegram channel and written in Cyrillic.

Nihilism and Gore

Figure 3: An edit of Timofey emphasising both gore and support of NVE groups.

While the attacker’s affinity and inspiration from the extreme-right is abundantly clear, the presence of some NVE ideas is important to note, given the rise in both perpetration of, and responses to, such attacks. This subculture of extremist activity is driven by misanthropy and the belief in the uselessness of life. In some cases, networks that encourage and distribute NVE material are also connected to extreme-right groups. Rather than replacing ideology, NVE here appears to function as an aesthetic orientation that coexists with and amplifies extreme-right meaning (in this case, the white race). Regardless of ideological perspective, the traces are evident in Moscow; during the attack, the perpetrator wore a T-shirt reading ‘No Lives Matter’ and previously wore a NLM patch on his vest – both the name of a group and a general motto for this movement. Similar items and references were made by the Antioch High School shooter earlier in 2025.

The attacker’s manifesto was titled “My Hate” or “My Anger” and refers to hatred of society, of life, and of other races, as a motivating factor several times. The perpetrator talks about his loneliness, stress, and disgust at having to be a part of society without having been asked. This is followed by statements about the meaninglessness of life and telling the reader explicitly that society is to blame: “YOU are the reason for this,” he says. Much of this aligns with previous identification of antisocial feelings as common throughlines among NVE actors, where social alienation is mapped onto feelings of meaninglessness, hate and violent responses.

Subcultures such as the True Crime Community (TCC) circulate and engage with video content showing or celebrating acts of violence and often gore. It is further evident from references in the document and elsewhere that he had consumed footage of attacks on social media. Following the attack, he posed with the body of the 10-year-old victim before a failed hostage-taking and the eventual arrest.

Reception

In the GoreBox Telegram channel populated largely by young people, memes gamifying the attack, many AI-generated, expressed both approving and disavowing perspectives; regardless of motive, these examples should be seen as lowering the seriousness with which acts of such violence are perceived, engaging ironically through memeification. The effect here can be to take severity away from the attacks and effectively desensitise toward violence, in turn lowering empathy and inhibitions, even if the created content was in opposition to the attacker.

Figure 4: A meme depicting Tarrant and the Moscow attacker. Tarrant asks: “Timofey what are you doing?” to which Timofey replies “This is ROFLS”

In the group chat of a Russian right-wing extremist, images of the attacker were further shared and quotes from the manifesto attributed to “Timothy the kid.” His youth provided these users with an additional aspect to be celebrated in his commitment to the Russian white race at such a young age. Notably, this brief flurry of attention quickly ended, and said group chat moved on within days. These two positions – the memeification and the fleeting, localised extreme-right celebration – serve as examples of the ephemeral, momentary nature of smaller-scale right-wing terrorism in an information space crowded with such events, constantly moving on to the next.

Conclusion

The Moscow attack demonstrates the continued presence of NVE-influenced activity online, which has been present in Eastern Europe for some time, facilitated in this case by the intermixing with extreme-right violent texts from across several continents. It demonstrates the malleability of NVE-aligned groups and ideals to meld with more openly ideological and long-standing positions rather than the generalised rejection of meaning and identity, in this case, appearing to present both personal grievances and instability mediated through Islamophobic white supremacy. This is a difficult line to draw and requires further clarification in research and practice to ensure accurate responses are possible.

Another stand-out area for concern is the youth aspect; NVE groups have been known to deliberately target young people, particularly those who are vulnerable or experiencing personal issues. This is the same demographic from which many extremist actors are drawn. While less regulated apps like Telegram continue to host youth communities, there is less opportunity to intervene. In the absence of enforceable international regulation – given its susceptibility to political reversal or user displacement across platforms – a wider societal change is required to address the factors driving interest and participation in extremism. Over-securitising youth as a response can also push to increasingly secretive and subversive behaviours; social infrastructure, mental health affordances and community-driven care are likely to be more effective and less negatively received in spaces where teenagers post edgy content and express distaste for societal institutions. In the near term, platforms can focus on reducing the circulation of manifestos through cross-platform flagging, potentially even identifying manifesto-style language as it is uploaded, based on content that often emulates known examples, while longer-term prevention depends on broader social support.

The attacker’s activities highlight the significance of small, community-based chats as spaces where personal interests can function as outlets for ideological expression and the rehearsal of violent fantasies, without necessarily making intent explicit. Moving forward, this case provides insights into pre-attack activities and into the expression of ideological beliefs in digital chats, as seen in the digital footprints of prior attackers. Understanding the escalation signs of extremist behaviour in minors who engage with extremist-inspired gaming content but have not yet triggered monitoring for violent behaviours is a crucial step. P/CVE practitioners will need awareness of the entire digital ecosystem to make useful interventions, including knowledge of the social spaces where vulnerable individuals spend time and the signs and symbols associated with such threats.

–

Harrison Pates is a PhD student in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. His research explores the contemporary far-right and their use of historical narratives for ideological purposes, generally on social media & elsewhere online. Harrison is also Project Manager at the Repository of Extremist Aligned Documents (READ), a special project of the Centre for Statecraft and National Security (CSNS).

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.