This Insight is part of GNET’s Gender and Online Violent Extremism series, aligning with the UN’s 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence.

Despite the territorial defeat of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in 2019, IS’s online caliphate continues to expand in tandem with the ever-evolving digital communications landscape. Social media has offered transformative opportunities for the jihadist group to streamline, outsource, and finance their militant Islamist agenda at a pace never witnessed before. Central to IS’s digital propaganda is the strategic deployment of gendered narratives, through which it reinforces patriarchal control and mobilises online supporters. This Insight will discuss the violently misogynistic narratives championed by IS recruiters and supporters across social media and the long-term risks associated with producing and accessing this content.

As women are more likely to be recruited online, effective content has become critical to the radicalisation process. Within the past year alone, there have been notable incidents involving female online recruiters and cells in Spain, Uzbekistan, the UK, and Singapore. These events underscore both the global outreach of female-driven recruitment methods and the continued promotion of IS and its harmful ideology, fuelled by the submission, self-sacrifice, and secondary status of women and girls.

Gender in the Islamic State’s Islamism

Gender inequality is fundamental to IS’s interpretation of Islamism. Women’s participation and membership in IS is predicated on their commitment to a ‘feminine identity’ that promotes helpless vulnerability, submission, chastity, motherhood, and unwavering support and encouragement of the Mujahideen (those who engage in jihad). Accordingly, pro-IS social media content exploits these gendered narratives to finance and venerate the inequality of women’s roles and status as normalised by the terror group.

Throughout November 2025, I collected, analysed, and Google-translated hundreds of gender-driven posts across Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram. Using keyword searches, I was able to locate accounts with highly questionable content. It was only after I pored over these accounts, including their follower lists and reposts, that I stumbled on gender-informed content that either alluded to supporting IS or encouraged acts of violent extremism such as jihad. In the analysis below, the majority, if not all, of the content was found on accounts reportedly run by women to emphasise how singular themes of womanhood and gender are pervasive across the network of violent extremist propagandists.

Fundraising ISIS: Capitalising on the Vulnerability of Women and Children

Stories of the 42,500 detained women, children, and female relatives of male IS suspects detained across al-Hol and al-Roj refugee camps in northern Syria have resulted in financing streams for the terror network and its members. Narratives of shared suffering, sisterhood, and loss of the nuclear family feed into fundraising campaigns targeting supporters abroad. The content is persuasive, often featuring crying children, derelict tents, and emotional appeals to help free “captive” Muslims and orphans. Granted, many pleas are for basic essentials, but the content advocating for the release of captive Muslims—both brothers and sisters—is likely a reference to IS members held at prisons in Idlib and their families, who are primarily held at al-Hol and al-Roj camps, a detail some may not consider before donating to a cause.

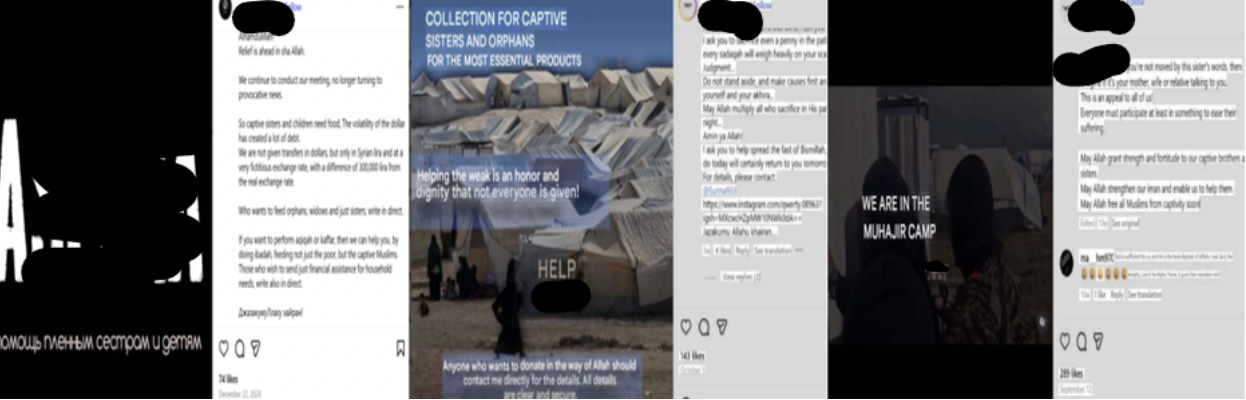

Figure 1: Fundraising for the “Widows and Orphans” of Al-Hol on Instagram

These charity organisations and potential fronts for IS fundraising often remain active through manipulating platform features and language choices. In the Instagram posts above, two charity organisations capitalise on sympathy for women and children, whom they strategically rename “captive sisters, widows, and orphans.” The specific language transforms questionable “detainees” into victims facing injustice and loss. Although the rhetoric is suspect, these pages have managed to remain up and active without long-term intervention from Trust and Safety teams for more than a year. Moderation teams would have to be thoroughly discerning as the content does not blatantly support the terror group, but the locations, circumstances, and context clues mentioned strongly suggest these campaigns benefit detained IS members and their families.

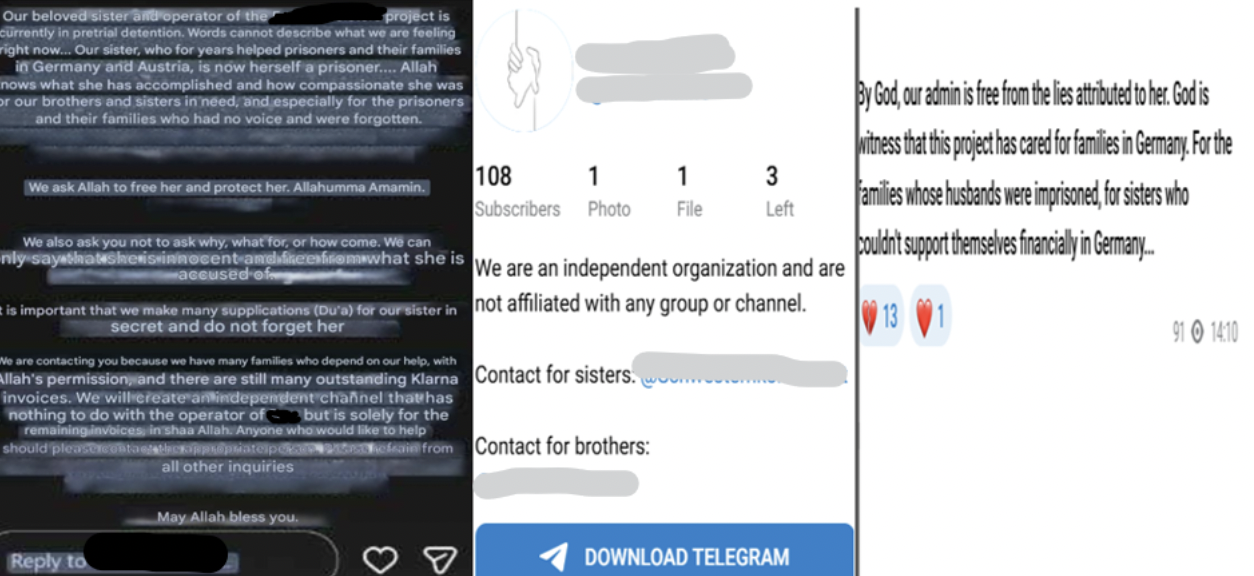

Figure 2: Instagram Announcement of Fundraiser’s Arrest, Telegram Channel, Telegram

Caption excerpts: (Far left Instagram story) “Our beloved sister [redacted] is currently in pretrial detention… who for years helped prisoners and their families in Germany and Austria, is now herself a prisoner…. Allah knows what she has accomplished and how compassionate she was for our brothers and sisters in need, and especially for the prisoners and their families who had no voice and were forgotten… We also ask you not to ask why, what for, or how come. We can only say that she is innocent and free from what she is accused of.”; (Far right Telegram post) “By God, our admin is free from the lies attributed to her. God is witness, that this project has cared for families in Germany. For the families whose husbands were imprisoned, for sisters who couldn’t support themselves financially in Germany…”

Of the ‘Captive Muslim’ fundraising accounts I found across TikTok and Instagram, one German-language account has had a direct arrest in connection with the organisation. Although the account last posted in late January 2025, the Instagram Stories feature and a few posts on Telegram offered some insight into the charity’s potential terrorist funding activities in both Syria and Germany. While not officially confirmed, these Instagram and Telegram messages suggest that the administrator was arrested for helping IS “prisoners and their families in Germany and Austria.” In the far left image of Figure 2, an announcement of the arrest on Instagram instructed followers not to ask about why or how the administrator was arrested, purportedly due to increased monitoring of the page. The language of fundraising has proved vital to financing initiatives supporting “captive sisters and brothers” without raising any critical alarms across social media platforms. However, as the language becomes overused, the initiatives may be exposed for what they are—fronts for the financing of terror groups.

Weaponising Femininity: Generations of Self-Sacrifice and Second-Class Status

The Islamic State weaponises femininity as a barometer of the integrity of a family and the larger Muslim community in their practice of Islam. According to one angle of IS’s ideology, women and girls bear the brunt of dishonour and assumptions of carelessness towards religious duty, while men are victims deserving of absolution from shame caused by women. Social media posts reflect this attitude and further exploit the status of women as secondary to men, paradoxically presenting them as the guiding light for male piety, but also reinforcing their lack of agency in an identity only understood through its relationship to men. Below, content riddled with belittling instructions and unreasonable demands are thinly veiled as religious duties, where motherhood is exalted, martyrdom is romanticised, and self-blame is canonised as women’s only legacy throughout the caliphate.

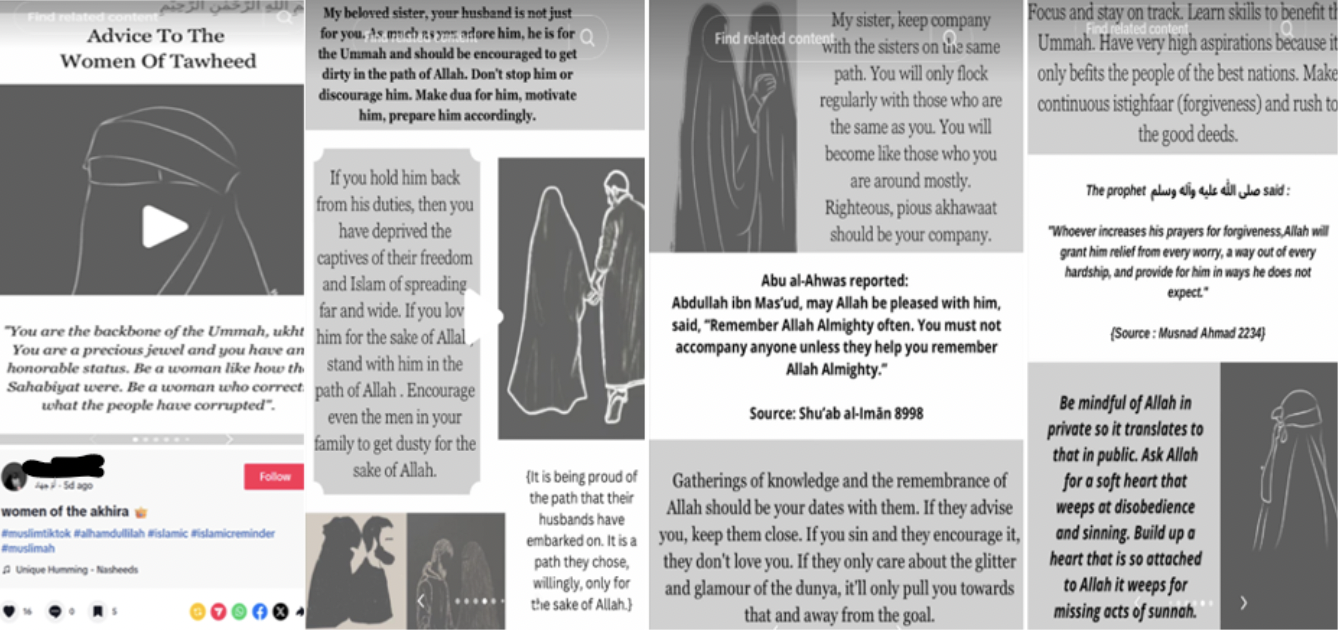

Figure 3: TikTok Pamphlet on Women’s Role in the Ummah

In Figure 3, a TikTok user offers an instructional manual on how to be a pious and respectful Muslima to ensure her husband’s undeterred path to jihad and her further obligation to “save” the Ummah (community of Muslims) from further corruption. The pamphlet lacks suggestions but is forthright in its demands regarding what women “should” do. Hate-filled and negatively charged rhetoric such as “you have deprived the captives of their freedom” and “if you sin and they encourage it, they don’t love you,” further punctuates the stigma associated with women who do not fulfil their “honourable status” as the “backbone of the Ummah.”

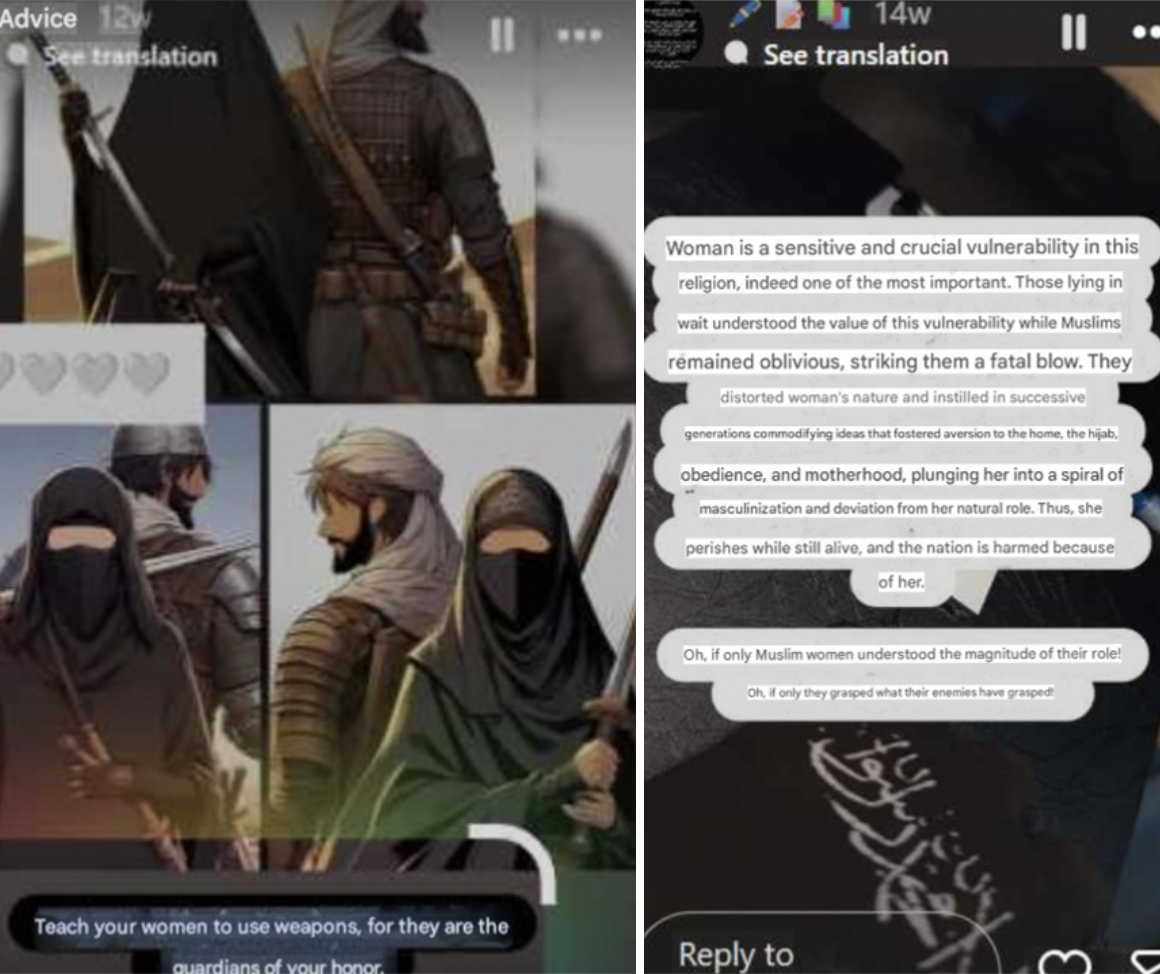

Figure 4: Instagram Stories of Women and Their Importance to Men

Caption excerpts: (L) “Teach your women to use weapons, for they are the guardians of your honor.”; “(R) “[Westerners] distorted woman’s nature and instilled in successive generations commodifying ideas that fostered aversion to the home, the hijab, obedience, and motherhood, plunging her into a spiral of masculinization and deviation from her natural role…the nation is harmed because of her.”

In the posts above, an Instagram user uses the Stories feature to post her text-filled animations and imagery depicting virtuous wives committed to preserving their husbands’ honour and masculinity. The left image advances weapons training for women, a somewhat progressive appeal. However, the justification remains male-centric, as a trained woman will be a better “guardian” of her husband’s honour. The training is not specifically for women, but rather an additional safeguard for the protection of men on their successful religious journey. Women are obligated to undergo the emotional labour of initiating and assuming responsibility for the honour that comes with a man’s successful pursuit of jihad. Gaining honour is exclusively granted to men, whereas preventing dishonour is the primary expectation imposed on women in pro-IS online spaces.

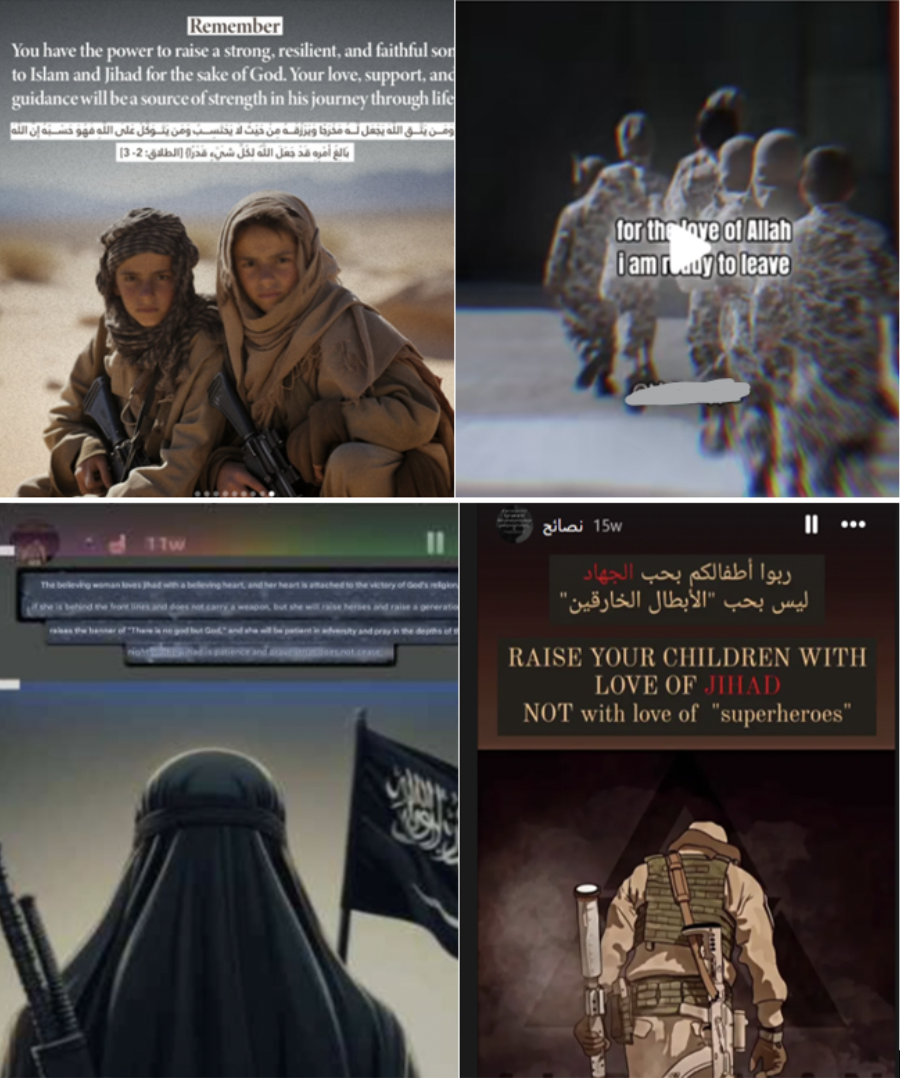

Figure 5: Maternal Instinct and Raising Jihadi Sons via Instagram and TikTok

Caption Excerpts: (Top Left Instagram post) “Remember: you have the power to raise a strong, resilient, and faithful son to Islam and jihad for the sake of God”; (Top Right TikTok post) “I advise them to love m @ rtyrdon”; (Bottom Left Instagram story) “The Believing woman loves jihad… she will raise heroes and nurture a generation that will uphold the banner,” (Bottom Right Instagram story): “Raise your children with love of jihad, NOT with love of “superheroes”

The jihadist political economy relies on motherhood, which affords women only a marginally enhanced status. Even in this capacity, their role remains constrained, as motherhood is militarised and instrumentalised to ensure a continued supply of fighters. The propaganda depicted in Figure 5 above seeks to convince mothers of their “power” in breeding the next generation of soldiers. The content is praise-focused and features lofty language such as “you have the power to raise a strong, resilient, and faithful son to Islam and Jihad for the sake of God.” Women are regaled but relegated to “raise heroes and nurture a generation that will uphold the banner,” to continue the fulfilling journey of jihad.

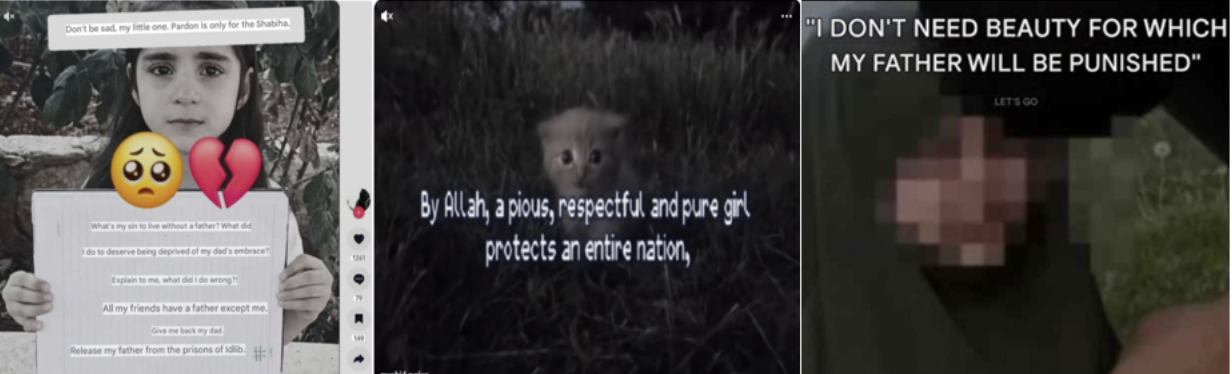

Figure 6: TikTok Posts Featuring Young Girls as Seen Through Fathers and the Nation

(L) What’s my sin to live without a father? What did I do to deserve being deprived of my dad’s embrace? Explain to me, what did I do wrong? All my friends have a father except me. Give me back my dad. Release my father from the prisons of Idlib; (C) By Allah, a pious, respectful and pure girl protects an entire nation; (R) “A little girl was asked: “Why are you wearing a baggy dress?” “I don’t need beauty for which my father will be punished.”

Young girls are also indoctrinated into a culture of self-abnegation for the plight of their father and the larger community. In the far left post seen in Figure 6, the girl’s sign reads, “what’s my sin?” and “what did I do to deserve being deprived of my dad’s embrace?” to underscore the shame she places on herself for his absence. The sensationalised narrative of women and girls as the true source of their husband or father’s pain and punishment remains unchallenged. Interestingly, some content appears targeted at young women, as if to soften the reality of their position. However, images of kittens do not mitigate the Herculean task imposed on girls to remain “pious, respectful, and pure” in order to protect an entire nation. Accordingly, there is no age limit to the narrative of self-blame as the post on the far right seemingly depicts a toddler stating she wears a niqab so that her father will not be punished for her vanity on the day of judgment. A girl’s purity and piety are not her own, but a decision made by the misogynistic narratives and imagery that shift the burden of blame from men to women and girls of any age.

Figure 7: Feminisation and Fantasisation of Jihad on Instagram

Captions: (L) If jihad were obligatory for women, the squares would be filled with Aisha’s granddaughters; (C) And the greatest thing between us is death and martyrdom; (R) And whoever has many sins, the greatest remedy for them is jihad

These three posts from another Instagram user are notable for their rudimentary composition. The content, which resembles aspirational quotes, cartoonish firearms, and a homage to the converse-sneaker-wearing sad girl aesthetic of 2010s Tumblr, comes across more as a teenage girl’s vision board than genuine ISIS propaganda. However, the fantastical imagery underscores how some women, including young women, idealise and dream of the otherwise inaccessible reality of jihad. The above aesthetic reveals the diverse profile of propaganda creators who manage to build an audience by employing linguistic patterns and nostalgic visuals even at the most basic level. The transformation of IS propaganda into mood boards and zeitgeist-inspired recruitment material not only makes the content accessible to the less religiously devout but also serves to desensitise audiences to the true severity of the content.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Improvements in content moderation are critical in disrupting the production line of misogynistic and violent content. While TikTok’s algorithm offers bespoke content, it can also reinforce ideological extremism. Within two days of my research, my “For You Page” prioritised videos blatantly supporting ISIS and calling for violence. Although the videos were quickly removed, integrating a review process that restricts or even delays the upload of dangerous content and rhetoric could prevent further familiarity with contemporary extremist agendas. Accordingly, Instagram and TikTok would benefit from dedicated research teams or organisational partners who specialise in and immediately alert content moderators of the changing language, keywords, imagery, and gendered tactics of radicalisation across social media platforms. Prioritising awareness of female recruitment tactics is also vital as the infrastructural integrity of the caliphate, both digital and otherwise, depends on women and their role in religion, societal traditions, and successful warfare. Defensive content moderation requires more than the removal of published content; it demands disrupting the echo chambers of misogyny and violence before the caliphate evolves from virtual reality into physical reality.

–

Riza Kumar is a Senior Analyst at the Counter Extremism Project where she focuses on extremist groups across the Sahel and West Africa. Her previous research includes the human cost of civilian-led counterterrorism militias and the judicial limitations of repatriating female foreign fighters from Syria. She holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Chicago and a BA in Gender Studies and Political Science from UCLA.

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.