On 14 August 2025, Thomas Daveson – identified as Thomas D. by the media – was arrested in Badhoevendorp, in the Dutch province of Noord-Holland. The 24-year-old suspect was accused of planning a terrorist attack and of possessing firearms. Thomas D. stated that he was part of the Dutch nationalist and identitarian youth organisation Geuzenbond. In a 2024 Bellingcat report, Thomas D. had already been identified as a regular attendee of Geuzenbond’s activities, such as the group’s annual “summer schools”, a 2023 public rally in The Hague, and the 2023 European Fight Night in Csókakő, Hungary. The individual in question also participated in the Remigration Summit on 17 May 2025 in Gallarate, Italy, according to Factanews, where Neo-Nazis and far-right groups converged from all around Europe. Participants at the Summit apparently discussed the remigration theory authored by far-right extremist Martin Sellner, who managed to attend the summit, despite being banned from entering some European countries.

Bellingcat has described Geuzenbond as “a Dutch affiliate of the white supremacist Active Club movement.” Adherents of Geuzenbond share extremist views on racial supremacy, ethnonationalism, xenophobia, and Eurosceptic ideology, particularly geared towards energising youth. Therefore, this Insight maps Geuzenbond’s online activities, and youth radicalisation and recruitment through social media. This analysis aims to assess Geuzenbond’s growth pattern and offer P/CVE recommendations to security officials and social media companies, based on the Terrorist Threat Assessment (DTN) and its associated Threat Levels, which are published every six months by the NCTV.

The Dutch T/VE Far-Right Extremist Landscape

The NCTV publishes two Terrorist Threat Assessments (DTN) each year with the aim to assess radicalisation and T/VE threats “to the Netherlands and to Dutch interests abroad”. The NCTV also laid out five threat levels depending on increasing estimates “of the risk of an attack in or against the Netherlands”. The latest DTN was released in June 2025, just a few months before Thomas D.’s arrest. In June, the NCTV had assessed a national threat level of 4: substantial, signalling “a real chance of a terrorist attack in the Netherlands”. The current threat level has remained heightened since it was raised to “substantial” in the December 2023 DTN. According to the June 2025 DTN, the main T/VE threats to the Netherlands stem from Jihadism and radical Islam, right-wing terrorism and extremism, anti-institutional terrorism and extremism, and, to a lesser extent, left-wing extremism. Regarding right-wing T/VE, the DTN notes that “the rapid radicalisation of young people online is a threat to national security”. More specifically, deep concerns were raised on the rapid online radicalisation of young men and boys and the possibility that “individuals or small groups may commit terrorist violence”.

In Chapter 2 of the June 2025 DTN, the NCTV highlights several key aspects of right-wing terrorism and violent extremism (T/VE). It notes an increasing number of young people active in online right-wing extremist networks, their rapid radicalisation, and the violent threat these online circles pose. These groups “encourage hatred towards others and pride in one’s own group” and “extremist language is actually rewarded with likes and words of encouragement”. The NCTV estimates that several hundred Dutch people – particularly minors and young adults – may be engaging in online right-wing T/VE. Sporadic in-person meetings may also occur. Moreover, right-wing extremist groups are increasingly collaborating with like-minded national and international groups, participating in “joint activities” and attending “each other’s events”.

According to the NCTV, the primary distinction between right-wing terrorist organisations and right-wing extremist groups active in the Netherlands lies in their relationship to violence, specifically, whether or not they employ or endorse it. Chapter 2 of the June 2025 DTN states that “unlike right-wing terrorists, most Dutch right-wing extremists currently advocate a non-violent path towards the white ethnostate they envision. […] But to bring about this ethnostate, they want to deport millions of people on the basis of their race, faith, sexual orientation or ‘unacceptable’ beliefs, something that cannot be done without the use of violence.”

The NCTV further highlights that politicians and society are becoming increasingly comfortable with the concept of ‘remigration’. The normalisation of right-wing extremist ideas brought forth by these groups seizing on societal discontent could ultimately lead to right-wing extremist violence: indeed, while direct threat of violence is still limited, the NCTV stressed that there have been “incidents [i.e. violence, vandalism, and threats] instigated by right-wing extremists”.

According to the data analysed for this Insight, Geuzenbond may fall under this second category. The group began its online activities in 2018 as a nationalist and identitarian youth organisation advocating for the unification of the Netherlands, Belgium and the French Flanders under one banner: that of the Greater Netherlands as vaderland (transl. fatherland). The pursuit of this ideology recalls the ‘white ethnostate’ vision that the NCTV deems a core pillar of right-wing extremism. This vision is regularly pursued through xenophobic, racist, and nationalist narratives. Initially, Geuzenbond made itself known through plaktivisme (transl. sticker activism), which it still regularly employs by placing stickers and posters in public spaces. One study estimated the group to have around 20 members in total as of 2024. As of 5 October 2025, Geuzenbond had 3,618 followers and 323 posts on its official Instagram profile, and 394 followers and 34 posts on its French chapter’s profile.

Geuzenbond’s Presence and Narrative on Instagram

For the purposes of this Insight, I analysed posts from the two official Geuzenbond profiles on Instagram, where the group primarily publishes original content to construct its narrative and disseminate its ideology. The analysis focused on posting habits, user interactions, narrative formation, and levels of user engagement. A random sample comprising 15% of all posts available as of 14 September 2025 was selected from each profile. This approach aimed to identify the overarching narrative advanced by Geuzenbond and to quantitatively assess audience engagement with its content.

I randomly selected a sample of 49 posts from a total of 323 posts from the group’s official Dutch profile (account #1).¹ A sample of 5 posts was randomly selected from the France-based profile (account #2), out of a total of 34 posts. Thus, 54 out of a total of 357 posts from Geuzenbond were analysed in relation to the number of likes, comments, and shares. Furthermore, I indicated the most frequent post format (photo, carousel, or video), location (mainly in the Netherlands, Belgium, and French Flanders), and language (Dutch or French). In the case of videos, I also indicated the number of views obtained. Finally, I identified recurring themes based on content to assess whether each of the randomly selected posts contributed to a broader establishment or amplification of the group’s violent extremist narratives (VENs) in line with Chapter 2 of the June 2025 DTN.

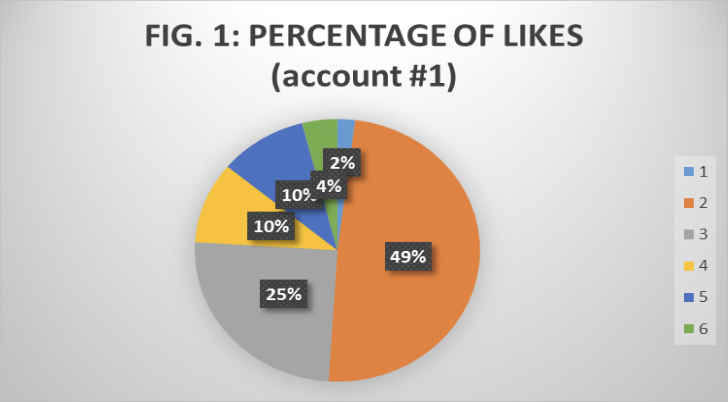

Fig. 1: Percentage of likes (account #1): 0-50 likes (1) = 2%; 50-100 likes (2) = 49%; 100-150 likes (3) = 25%; 150-200 likes (4) = 10%; 200-250 likes (5) = 10%; more than 250 likes (6) = 4%. Created by the author.

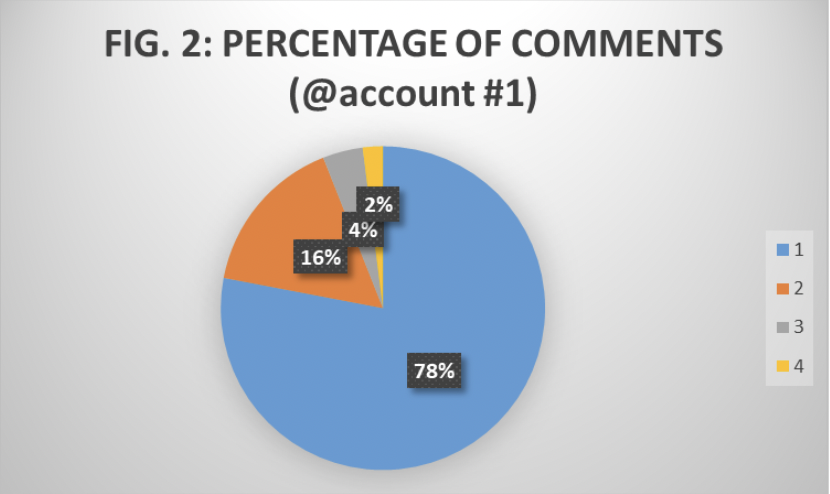

Fig. 2: Percentage of comments (account #1): 0-5 comments (1) = 78%; 5-10 comments (2) = 16%; 10-20 comments (3) = 4%; 20-30 comments (N/A) = 0%; more than 30 comments (4) = 2%. Created by the author.

Analysed posts featuring people are almost always pictured in small groups of young men, who appear to be university-aged students. Their faces are often blurred with Geuzenbond’s logo, pixelated, or covered with a mask, indicating that the group prioritises anonymity online. The group was most active in the Netherlands (in the provinces of Gelderland, Limburg, Noord-Brabant, Noord-Holland, Overijssel, and Zuid-Holland) and in Belgium (in the Flemish provinces of Brabant and Antwerp). As of 14 September 2025, posts from account #1 – most of which were carousels, closely followed by single photos – were only written in Dutch and were neither translated into English nor into French. This indicates that Geuzenbond primarily intends to target a Dutch-speaking audience.

Fig. 3: Plaktivisme post from account #1 featuring slogans on remigration and revolution.

A significant portion of Geuzenbond’s activity on account #1 is dedicated to showcasing plaktivisme efforts in those provinces. Posts show white and orange stickers with Eurosceptic, militarist, ethnonationalist, and xenophobic slogans such as ‘Europa jeugd revolutie’ (transl. ‘Europe youth revolution’), ‘Nationalist, je bent niet alleen’ (transl: ‘Nationalist, you are not alone’), and ‘Remigratie’ (transl. ‘Remigration’). Most stickers feature the Prinsenvlag (transl. Prince’s flag), which is designed with three horizontal bands of orange, white, and blue. The flag was first displayed during the Eighty Years’ War (16th century) by William of Orange, but became associated with Nazism after its usage by the Dutch National Socialist Movement (NSB) prior to and during World War II.

Fig. 4: Post from account #1 reinterpreting the 1917 Uncle Sam’s ‘I want you for U.S. army’ poster

Geuzenbond has also featured collaborative posts with other Dutch and Belgian right-wing extremist groups, such as Nationalistische Studentenvereniging (NSV) and Voorpost, to mark communal far-right gatherings or protests calling for remigration. Finally, posts also sponsor Geuzenbond’s publication, De Stormlamp, which acts as a blueprint for the association’s ideology. One of the covers featured was a reinterpretation of the 1917 Uncle Sam’s ‘I want you for U.S. army’ poster (‘De Geuzenbond wil jou’; transl. ‘Geuzenbond wants you’).

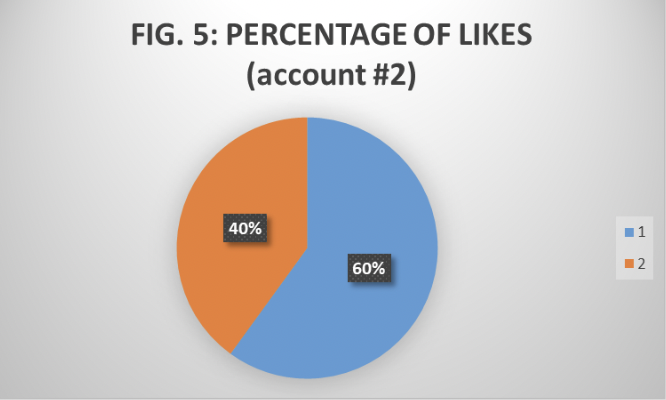

Fig. 5: Percentage of likes (account #2): 0-40 likes (1) = 60%; more than 40 likes (2) = 40%. Created by the author.

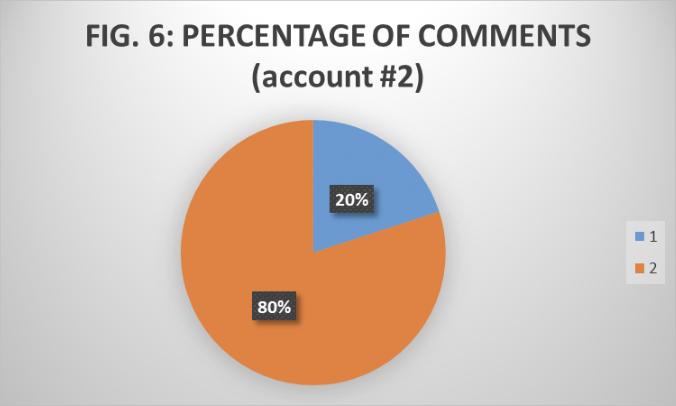

Fig. 6: Percentage of comments (account #2): 0-5 comments (1) = 20%; 5-10 comments (2) = 80%. Created by the author.

Compared to account #1, account #2 had a lower audience and lower metrics engagement per post. As of 14 September 2025, most posts from account #2 – both photos and carousels – were written in both Dutch and French, due to the history of the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments in the Hauts-de-France region, where the French chapter is active. Nonetheless, content showcasing plaktivisme efforts was favoured over content showing people: the main slogan featured read in both French and Dutch ‘La Flandre aux Flamands!’ and ‘Vlaanderen aan de Vlamingen!’ (transl. ‘Flanders for the Flemish!’).

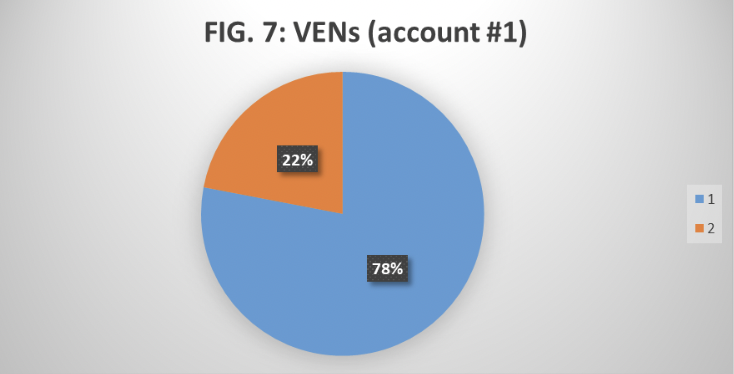

Fig. 7: VENs (account #1): Yes (1) = 78%; No (2) = 22%. Created by the author.

Fig. 8: VENs (account #2): Yes (1) = 80%; No (2) = 20%. Created by the author.

Quantitatively, 38 out of the 49 (78%) selected posts from account #1, and four out of the five (80%) posts from account #2, presented VENs in line with the June 2025 DTN. Both accounts pursue nationalist and racist narratives emphasising ‘taal, erfgoed, eigenheid’ (transl.: ‘language, heritage, identity’). In this context, non-Dutch citizens, non-Dutch speakers, migrants, and Muslims are often ‘othered’ and labelled as a threat. Through its plaktivisme, Geuzenbond also echoed the racist rhetoric associated with Zwarte Piet (transl. Black Pete), who assists Sinterklaas (transl. Santa Klaus) in handing out gifts in Dutch and Belgian folklore.

Fig. 9: Plaktivisme post from account #1 on Zwarte Piet.

Apart from remigration, Geuzenbond also strongly advocates for militarism and sports to build camaraderie among its members. In this regard, the NCTV indicated that “some Dutch right-wing extremists engage in physical training to protect the ‘white race’, in the context of ‘self-defence’. […] In the Netherlands, physical training combined with a lifestyle focused on masculinity, brotherhood and ‘white consciousness’ is, for the time being, mainly a recruitment tool to introduce young men to right-wing extremist ideas”. This confirms the demographic data on gender and age range collected for this Insight and further explains the role that online content produced by Geuzenbond on Instagram may play in radicalising these users specifically.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Over the past twenty years, fewer T/VE attacks were carried out in the Netherlands compared to neighbouring countries, such as France and Belgium. One of the reasons why is the so-called ‘broad Dutch approach’, which focuses on preventing violent extremism (PVE) through the “early recognition of radicalisation processes in both individuals and groups”. Expanding this PVE-oriented approach internationally may help concretely reduce both radicalisation and attacks. Furthermore, community engagement initiatives should aim to educate young people – especially young men and boys – about the VENs that are spread on the web and on social media. These initiatives should equip them with the tools and awareness to identify and contrast VENs (such as reporting or flagging extremist or violent extremist content).

In the Instagram Community Guidelines FAQs, it is clearly stated that “support or praise of terrorism, organised crime or hate groups, [as well as] attacks or abuse based on race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, disability or disease [are not allowed]” and that “credible threats of violence, hate speech and the targeting of private individuals [are removed]”. Hence, social media companies should play a bigger role in identifying, flagging, and preventing the spread of VENs. The Dutch ‘person-centred approach’ may be a powerful tool if combined with the growing personalisation of social media AI-driven algorithms. Firstly, this may be useful in identifying those on the path to radicalisation, as well as individuals who have already been radicalised. Finally, AI algorithms may be trained not to recommend VEN-promoting content, thereby limiting vulnerable users’ interaction with potentially subversive or incendiary ideas. During my analysis, Instagram began recommending further far-right extremist-leaning content, as well as following Geuzenbond’s or similar right-wing terrorist groups’ profiles. Hence, previous repeated user interaction with VENs inevitably leads to the creation of filter bubbles and echo chambers. In turn, this may reinforce online youth radicalisation.

Lastly, research from bodies such as the High-Level Commission Expert Group on Radicalisation (HLCEG-R) and the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) may lead to significant progress for both EU institutions and major tech companies in better understanding the nexus between AI-driven algorithms and user radicalisation. Further research should thoroughly investigate the networking and affiliations among Dutch right-wing extremist groups on mainstream platforms such as Instagram.

Endnotes

- GNET does not include usernames of users deemed to be extremist/extremist adjacent. The two accounts are thus referred to as account #1 and account #2 that the group had.

—

Paola Testa is a Senior Analyst for the Defence and Security Desk at Istituto Analisi Relazioni Internazionali (IARI), where she previously collaborated for the Middle East and North Africa Desk. Paola is an Events and Communications Officer at the Young Ambassadors Society (YAS), the official Italian youth engagement group to the G7 and G20. She served as a YAS Y7 Observer (G7 Italy 2024) and as a YAS SB62 Delegate in preparation to COP30 (UNFCCC). Paola is a member of the European Student Think Tank, where she is serving her second mandate as the 2025 – 2026 Ambassador to Italy. Her experiences in geopolitics and youth advocacy are reinforced by her Bachelor’s degree in Linguistic Mediation in Italian, English, German, and Arabic and by her Italian-French EsaBac double degree. X: @pao_la003

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.