Introduction

On 31 July 2024, Indonesia’s Counterterrorism Special Detachment 88 (Densus 88) arrested a suspect in East Java accused of being an Islamic State (IS) sympathiser. The suspect was identified as HOK, a 19-year-old student who was allegedly radicalised online and pledged allegiance to IS through a social media application. He frequently accessed websites and social media to obtain propaganda materials and information on bomb assemblies to target two places of worship in the East Java area. Furthermore, during Pope Francis’ visit to Indonesia in September, seven terror threat actors were apprehended by Densus 88. These seven individuals made statements about carrying out attacks during the Pope’s visit on various social media platforms, including TikTok. Outside of Indonesia, notably in Austria around an alleged plot to target a Taylor Swift Concert, the suspects were also, apparently, radicalised on TikTok.

Indeed, IS’s presence on TikTok seems to have created a new caliphate in cyberspace called ‘CaliphateTok’. Like IS in the real world, CaliphateTok spreads its propaganda and incites similar operations in other countries, in this case, Indonesia. This aligns with IS’ strategy of spreading its ideology globally by adapting to the local context of each target country. TikTok, as one of the social media platforms with the largest number of users, particularly youth, has become a new tool for spreading potentially violent ideological extremism and recruiting new members. It would be very concerning if this large group of young people were frequently exposed to extremist content, as in the case of two teenagers and an Austrian man of Chechen and Bosnian descent in 2023. Conversely, this large user demographic advantage can be leveraged by the stakeholders working on countering extremism to create counter-narrative content encouraging young people to prevent extremism.

In light of the recent arrests of alleged young IS sympathisers in Indonesia and Austria, this Insight explores how IS targets young users through symbols, narratives, and visual propaganda tailored to popular culture and digital trends. The narratives constructed by IS, especially on TikTok, often seek to glorify jihad, promote violence, and attack the government. This Insight shows how such narratives are exploited to motivate, recruit and mobilise young sympathisers. Additionally, it examines the potential of moderating extremist content through a counter-narrative on TikTok and the efforts of various stakeholders to curb the spread of radicalism and extremism. The findings could provide further insights into the role of social media in spreading extremist ideology and the importance of more effective responses to the threat of digital extremism.

The CaliphateTok

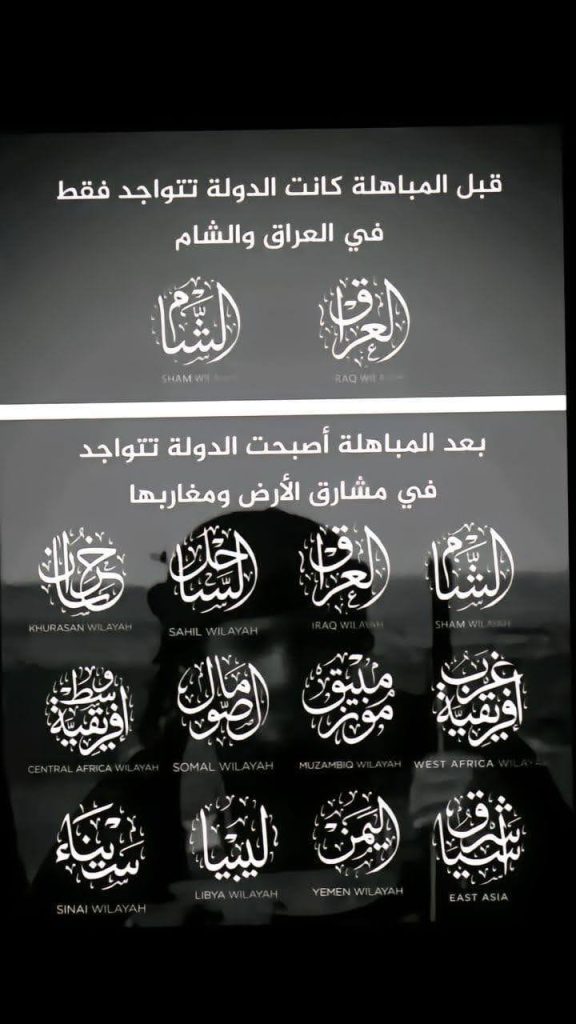

With the loss of its geographical authority in Iraq and Syria, IS has shifted their operations and resources to offshoot groups they have in other regions as a form of adaptation. Loosing physical territory also means that they have to intensify their presence in cyberspace to continue their ideological struggle and coordinate their operations. Figure 1, which was found circulating on TikTok, highlights IS’ various regional branches. The image was found on an account that uploads a lot of propaganda content about IS, and has around two thousand followers at the time of writing. Content pertaining to IS’ branches became the most engaged content with more than 50,000 views.

Fig 1. A propaganda image that shows the expansion and establishment of IS in other regions such as Khorasan, Africa, and East Asia

IS requires platforms that facilitate the rapid and effective distribution of their ideology. Consequently, social media serves as an effective instrument for spreading their influence. Platforms like TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and Telegram create an environment that significantly benefits groups such as IS in their operations. These social media platforms enable IS to connect with a younger, global, and vulnerable audience. TikTok has emerged as a highly effective platform for IS to disseminate its narrative. The features of TikTok, particularly the For You Page (FYP) algorithm designed to align with user behaviour, facilitate the effective targeting of IS content to its intended audience. The videos have the potential to rapidly gain broad recognition, attracting the attention of users who might have encountered them without prior awareness. This provides IS with a significant mechanism to influence an individual algorithm, thereby enhancing the exposure of their extremist message.

Users who continuously interact with related content will be more frequently exposed to propaganda through algorithmic recommendations, which automatically increases the “engagement” of that content. Interactions in the form of likes, comments, or shares will reinforce this cycle, trapping users deeper into the online radicalisation environment.

Despite TikTok’s efforts to remove IS-sympathising content, including videos that violate community rules, and to shut down the accounts involved, the group continues to re-emerge with new accounts. This poses a challenge for social media platforms in controlling the growing phenomenon of digital radicalisation. This phenomenon may be dubbed ‘Digital Jihad,’ where IS sympathisers are not afraid to have their accounts blocked, deleted, or even tracked by law enforcement.

Anti-Government Narrative

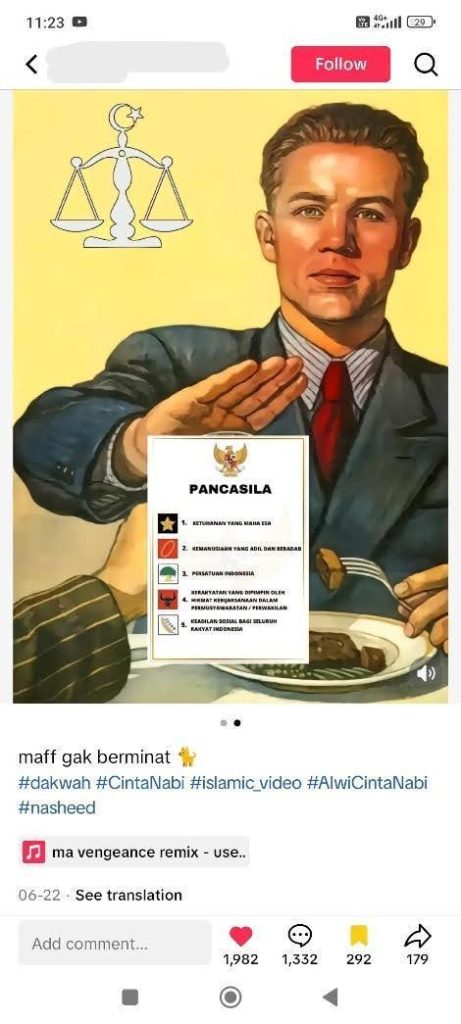

Propaganda by IS supporters in Indonesia often call for the rise and establishment of an Islamic state, opposing the current concept of a state based on the five principles of Pancasila. Indonesia’s ideological foundation of Pancasila serves as a guidance to govern the country and a way of life for its citizens. Meanwhile, IS sympathizers reject Pancasila, which they consider to be a man-made creation and not a law from God, and therefore illegitimate as a basis for establishing an Islamic state. In the view of this group, Pancasila is considered a taghut (Arabic term for a government that rules based on manmade law), as they believe that only God’s law (sharia) should be the foundation of the state. The rejection of Pancasila defies the reality that its values are fundamental for preserving Indonesia’s diversity, a country with a population of various ethnicities, races, religions, and cultures.

IS sympathisers also use memes as a propaganda tool. This use of memes has two primary purposes. Firstly, memes framed with humour are used to attract followers, especially the younger generation, more engagingly. This tactic is part of what is known as ‘meme warfare,’ where heavy ideological messages are presented in an easily digestible form. Secondly, by using memes, these groups seek to disguise their extremist messages, making them harder to detect by social media platforms or law enforcement. Memes’ non-serious or humorous nature allows their propaganda to be widely disseminated without being immediately recognised as radical content.

Figure 2: A TikTok video titled ‘Islamic State has risen’ featuring Aman Abdurrahman’s photo when he was sentenced to death. He founded Jamaah Ansharut Daulah who supports ISIS and carried out attacks in 2016-2017 in Indonesia

Figure 3: Use of No! Poster memes to show rejection of Indonesia’s Pancasila ideology in favour of Islamic sharia law

Glorification of IS Activities in Other Regions

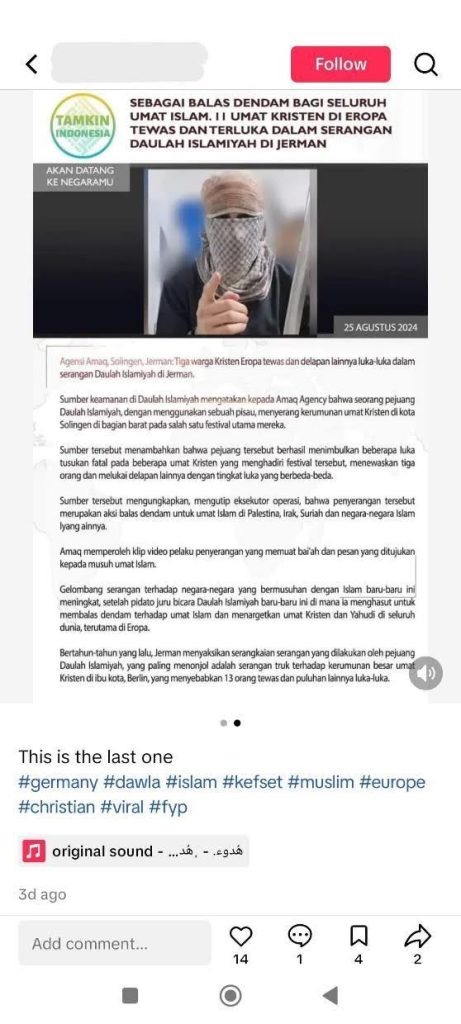

In addition to spreading anti-government narratives in Indonesia, IS supporters also amplify news of recent terror attack in other countries, using them as part of their broader propaganda strategy. They seek to link violent acts committed by IS in various countries as part of their global agenda, reinforcing the idea of transnational jihad. For example, a TikTok video found in Bahasa Indonesia with the logo of Tamkin Indonesia featured news about a stabbing attack in Solingen, Germany, that occurred on 23 August 2024. The video promotes a narrative that glorifies the attack as a heroic act and a form of opposition to Western countries.

Figure 4: A snippet of Tamkin Indonesia’s online news on TikTok announcing the Solingen attack followed with hashtags ‘germany’, ‘viral’, ‘fyp’

The news in the video cited Amaq Agency, an IS-affiliated news agency, as the main source of information. Amaq is known for publicising IS claims of responsibility for terrorist attacks around the world. The video portrays the attack in Solingen as an act of revenge against what it claims is the oppression of Muslims in the Arab world. The attack is portrayed as part of the resistance against the enemies of Islam, especially the Western countries.

Such content amplifies security risks, especially with the increased potential for lone wolf attacks or individual attacks inspired by terrorist propaganda with no direct affiliation. With the glorification of attacks, those inspired by the narrative may feel compelled to commit similar acts in support of IS’ agenda. European countries considered hostile to IS should further increase their vigilance against potential domestic attacks inspired by extremist ideologies. Moreover, this phenomenon reinforces the need for international collaboration in countering online extremism and radicalisation.

Counter-Narrative as a Solution

Efforts such as filtering, moderating, removing content, and blocking accounts and hashtags that sympathise or support extremism and terrorism are still needed even though extremist groups seem to be increasingly resilient with technological developments. Perhaps what is needed is to strengthen effective collaboration with governments, civil society organisations (CSOs) and technology companies. This collaboration can raise mutual awareness and develop a more technically sound approach to making cyberspace safe from extremist groups.

Regulating technologically is not enough, as extremist content on social media is impossible to remove entirely. In addition to technical measures, a more profound initiative is required to develop counter-narratives that challenge extreme ideologies. These counter-narratives should be crafted to provide a more positive and constructive perspective, promoting peace, harmony, and tolerance. This may manifest as movies, campaigns, or messages emphasizing narratives of unity and dialogue among communities. Furthermore, partnering with influencers or content creators who espouse moderate and peaceful values might enhance the efficacy of the counter-narrative. Influencers possess significant allure among youth, and their active promotion of peace messages can serve as a strong tool for countering the influence of extreme content.

For example, a video by @kadamsidik who is a Muslim preacher with 6.1M followers on TikTok informed young people about the trend of radicalism spread by accounts with specific usernames. According to his findings, those accounts also serve as a channel that directs viewers to a radicalised telegram group. The video’s call to avoid such content has over 1.9M viewers and 282.6K likes. This means that the video can reach a large audience and has a significant impact on educating users, especially youth.

Figure 5: An educational video made by Kadam Sidik titled ‘Watch Out for Indications of Terrorism Among the Youth’

Conclusion

IS propaganda on TikTok has become a concerning phenomenon. Sympathiser content is filled with glorification of violence and anti-government propaganda designed to influence vulnerable individuals, especially those in search of identity or feeling marginalised. Therefore, we need to intensify our efforts to prevent and counter the spread of this propaganda. One strategy is to promote content that conveys positive narratives on TikTok and other platforms. Content that conveys moderate and peaceful messages will help shape a stronger sense of the importance of peace among youth. This is one crucial step in countering the influence of radicalism and creating a safer and more inclusive digital space.