Introduction

The spread of extreme right-wing propaganda on TikTok is a familiar problem. Admiration for fascist ideologues from the early to mid-twentieth century is a staple of such discourse on TikTok, alongside other platforms. This applies not only to Hitler and Mussolini but also to the raft of fascist ideologues who sought but failed to achieve their professed fascist revolution.

This Insight explores how ideologues from lesser-known fascist movements have featured in far-right content on TikTok and the implications thereof, focusing on three prominent forms of material. First, the deification of fallen fascists. Second, the regurgitation and diffusion of extremist beliefs held by such ideologues. Finally, the incorporation of bygone fascists into far-right memes.

To briefly clarify, none of this is to suggest that content centred on Hitler or Mussolini is not present on TikTok. Posts featuring an unmistakable admiration for the dictators were found among the litany of content explored. Yet the focus of this Insight is on comparatively less well-known fascist ideologues, not least because such material frequently escapes satisfactory content moderation.

Fascist ‘Martyrs’

The idolisation of fallen fascists using overt religious symbology is nothing new, the practice dating to the interwar period itself. More recently, researchers have witnessed the online deification of such mass killers as Dylann Roof, Anders Breivik, and Brenton Tarrant, forming part of a wider ‘Saints Culture’ amongst white supremacists. A not-dissimilar process has occurred on TikTok in relation to some of the lesser-known fascist ideologues. Two figures stand out in this regard.

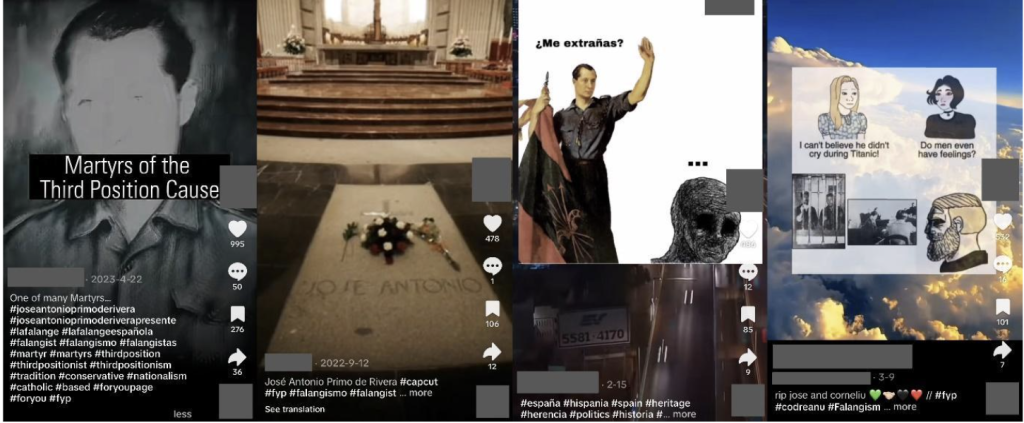

The first, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, was the founder of the Spanish Falange and was later executed in 1936 for conspiracy against the state. One falangist account explicitly cast Primo de Rivera as a ‘martyr’ and the ‘GOAT’ of the third position cause, a neo-fascist creed with its roots in, amongst other sources, the thought of Otto and Gregor Strasser, both of whom were early ideologues of an anti-capitalist strand of Nazism. Other accounts depicted his tomb or expressed their veneration for the fascist leader through memes. For example, one post featured Primo de Rivera asking whether he was missed (‘¿Me Extrañas?’). The response to this question was captured beneath by a visibly depressed ‘Withered Wojack’ (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Depictions on TikTok casting Primo de Rivera as a martyr.

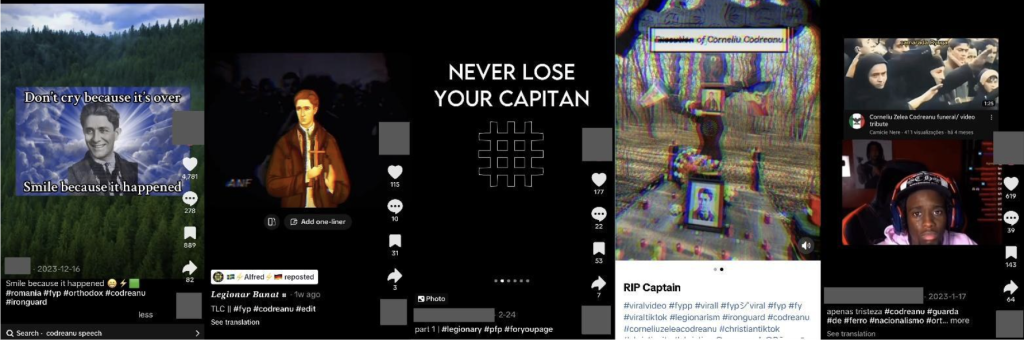

The second figure commonly mentioned in this context is Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, founder of the Romanian Legion of the Archangel Michael (more commonly known as the Iron Guard). Many posts expressed sorrow over the loss or deep gratitude for the sacrifices of Codreanu, not least by quoting from his Prison Diaries. For instance, as a pro-Legion account proclaimed, one ought ‘Never Lose Your Captain’, a reference to Codreanu’s own Duce- or Fuhrer-like title. The imagery of Codreanu regularly features him in a saint-like pose brandishing a cross; some posts even depicted his tombstone or the commemorative Cross of Tâncăbeşti. Another picture cast a smiling Codreanu amongst the heavenly clouds, exhorting viewers not to ‘cry because it’s over’, but ‘[s]mile because it happened’ (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Depictions on TikTok casting Codreanu as a martyr.

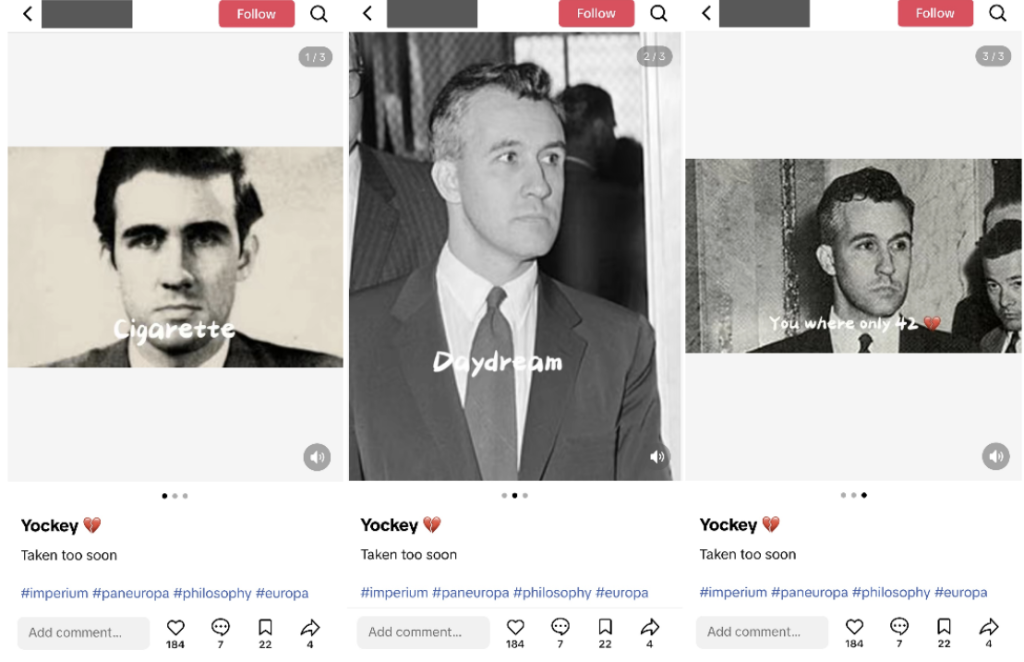

Beyond these two individuals, other ideologues sporadically appear in similar contexts. One post, for example, quoted the final words of William Joyce, a British fascist turned German wartime propagandist, prior to his 1946 execution: ‘In death as in life, I defy the Jews who caused this last war… I am proud to die for my ideals and I am sorry for the sons of Britain who have died without knowing why’. Another post by the same user depicted John Amery, a British fascist and Nazi collaborator, who was likewise executed. Accompanying the post is a single hashtag: #Martyr. Referencing the song ‘Cigarette Daydream’ by Cage the Elephant, another account lamented the death of the infamous neo-fascist author, Francis Parker Yockey, who committed suicide following his arrest in 1960 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Screenshot of a post lamenting the death of Yockey.

Turning to the Past

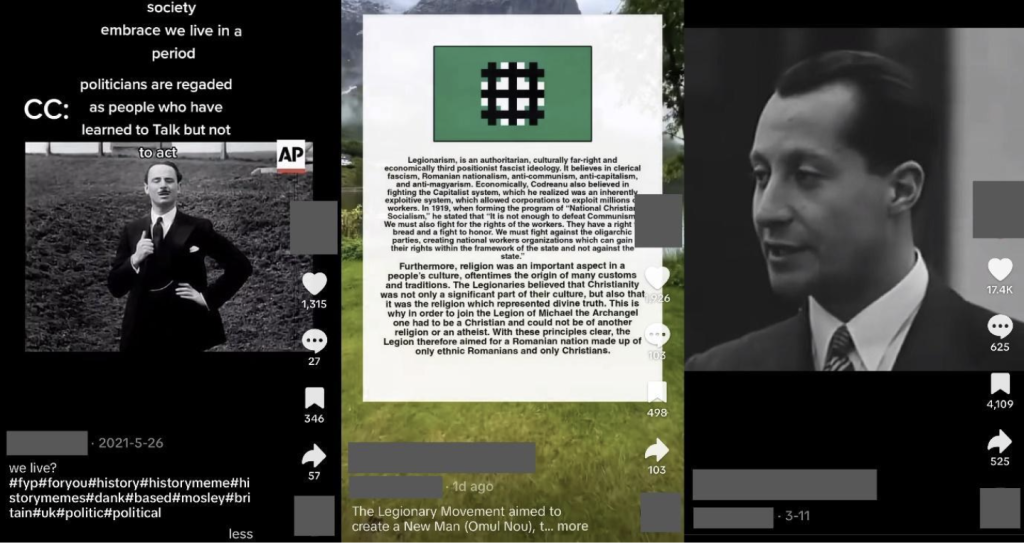

Several posts recommended ideological tracts penned by interwar ideologues. For some, this involved showcasing historical texts released by contemporary far-right publishing houses, such as the white supremacist Antelope Hill Publishing or the fascist nostalgists at Steven Books and Black House Publishing. For instance, one deeply antisemitic and avowedly fascist account compiled a list of ‘8 books on fascism people should read’, alongside another reading list entitled ‘7 books on fascism/benito mussolini’s ideology’. Amongst others, these compilations included tracts by Oswald Mosley, founder of the interwar British Union of Fascists (BUF); court philosopher of the Italian regime, Giovannie Gentile; and leading BUF philosopher, Alexander Raven Thomson.

More commonly, swathes of content focused on relaying quotes by historical fascists. These are typically of a lofty tone, which convey not only a general admiration for bygone fascists, but extremist beliefs and a commitment to the ideological struggle of their forebearers. For example, one self-proclaimed ‘clerical fascist’ posted a quote by Julius Evola – a frequent staple of far-right posts on TikTok – who had extolled adherents to ‘never abandon the principle of struggle’, nor accept what ‘they [i.e., their ideological foes] call the reality of life’. Alongside many posts centring on the political thought of Primo di Rivera and Codreanu, another recurring personality is the aforementioned Mosley. Numerous posts hold Mosley in high esteem as a courageous leader and a deep political thinker. Among other figures that occasionally appear was the neo-fascist Yockey; the treasonous Joyce; leader of the interwar Belgium Rex and notorious Holocaust denier, Léon Degrelle; founder of the American Nazi Party and former leader of the World Union of National Socialists, George Lincoln Rockwell; and Ion Mota, a key member of the Iron Guard later killed during the Spanish Civil War (see Fig. 4). Notably, several identified posts and accounts supplied links to facilitate migration to less-moderated platforms, in particular Telegram.

Figure 4. Sample of posts featuring the propagation of fascist ideologues and ideology.

Memes and Metapolitics

Alongside, and partly overlapping with, the deification of past ideologues and the propagation of their thoughts, a number of TikTok users co-opted such figures in the production of far-right memes. Through ‘comedic’ associations with far-right views and by riffing on aesthetics and jokes from a wider meme culture, many interwar ideologues are cast as figures with whom the audience is meant to admire or relate.

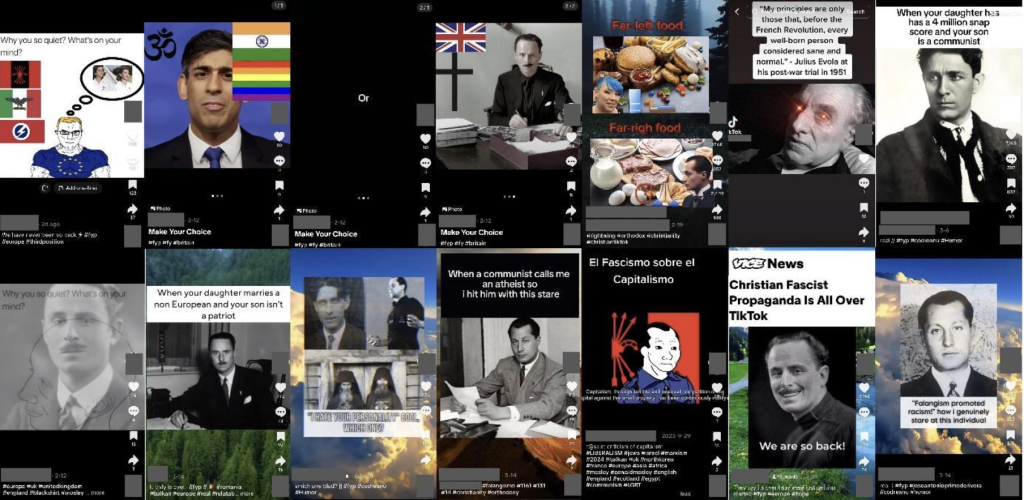

One user posted a video featuring Codreanu, captioning it with the phrase ‘Anotha legionary classic’; the latter a reference to the ‘Aryan Classic’ meme. Importantly, though, many posts regularly borrow from other arguably more popular or mainstream memes, from ‘Withered Wojack’ to ‘Yes Chad’. One post, for example, featured Primo de Rivera in the artistic style of a Wojack; others depicted Evola and Sima emblazoned with laser eyes (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Sample of far-right memes featuring interwar fascist ideologues and movements.

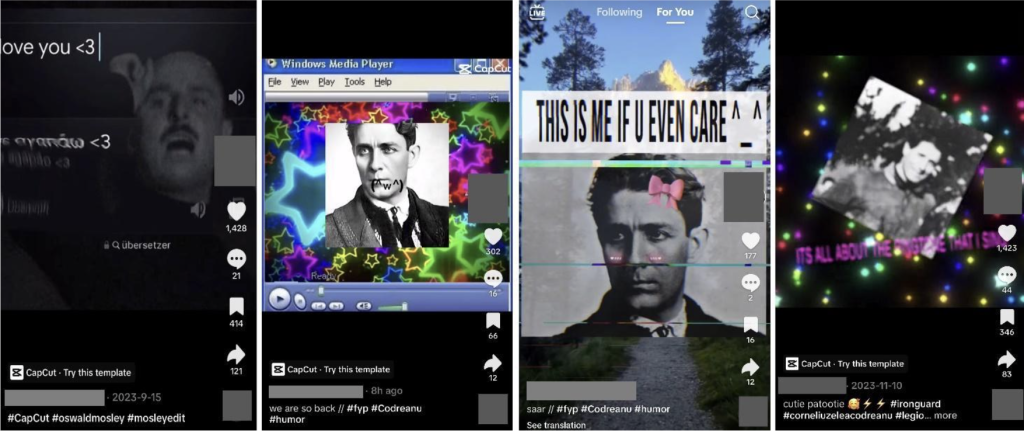

In a similar vein, some posts featured a sycophantic, yet comedic, admiration for fascist leaders, presenting them as cute and loveable (Fig. 6). In general, such memes seek to trivialise extremist content, not least by drawing from the comparative mainstream of meme culture. In the process, this content contributes to the broader memetic struggle waged by factions on the extreme right.

Figure 6. Sample of memes expressing a crush on the fascist leaders or casting them in peculiarly cute manner.

Implications for Content Moderation

The identified posts highlight important gaps in content moderation. Broadly, they reveal the need for TikTok’s trust and safety team to expand and update the range of flagged imagery and terms associated with hateful and extremist content. This necessitates an attentiveness to how extremists deploy historical referents not simply from Italy and Germany, but the wider transnational history of twentieth-century fascism, from minor fascist ideologues and movements to the titles of their ideological tracts.

With that said, TikTok will need to fine-tune its capacity to distinguish between content designed for genuine educational or other benign purposes, versus those that betray an ideological admiration or hateful intent. For example, searching TikTok for videos of Mosley will return a number that features the actor Sam Claflin, who played the villainous BUF leader in the BBC series Peaky Blinders. In this case, an outright ban on searches for Mosley may not be desirable. In fact, it appears that TikTok has already implemented a tiered system of moderation to address this type of problem, albeit only in regard to some terms already flagged. For instance, querying TikTok’s search bar for Léon Degrelle returns a redirect message, which encourages users to ‘verify the facts and trust credible sources when seeking information about the Holocaust and its legacy’. No content is displayed, but rather a link to the aboutholocaust.org website. This intervention is understandable: Degrelle is an obscure figure, confined largely to extremist circles. By contrast, Hitler’s name appears in a range of benign educational, pop-culture, or political (yet not necessarily extremist) contexts. It may be for this reason that the app still provides users with results for ‘Hitler’, albeit prefaced by a cautionary banner to ‘consult trusted sources to prevent the spread of hate and misinformation’.

There are four challenges that TikTok must confront in seeking to redress such violative content without curtailing benign material. First, there is a need for TikTok to more thoroughly address content that makes problematic recourse to historical fascist referents by expanding and refining its existing moderation protocols. Those involved in developing TikTok’s moderation policies are not, of course, oblivious to wider historical references. TikTok has expressed its commitment to continually update its designation of ‘dangerous and hateful individuals and organisations’. Indeed, the existing system flags several such terms associated with historical fascist movements, including Vidkun Quisling, head of the Norwegian Nasjonal Samling and Nazi collaborator; Ante Pavelić, leader of the Croatian Ustaše; and the aforementioned Degrelle. However, as the foregoing discussion demonstrates, not least the hundreds of posts identified in the process of this research, there is considerable space for improvement.

TikTok would be sensible to extend its moderation procedures to a raft of additional terms, in particular Codreanu, Primo de Rivera, Mosley, Third Positionism, and Falangism (alongside logical deviations, e.g., Falange, Falangismo, etc.). This will necessitate expanding its hashbank of flagged keywords and automating the removal of identified hateful content; affording effective training material for human moderators to identify such content; and – as in cases where the mainstream obscurity of an ideologue almost ensures that any content is of a dubious character – applying warning banners or outright limiting the searchability of relevant hashes.

Second, while moderation tools must be cautious not to stifle benign content, text-based technologies and human moderators must learn to successfully identify harmful content that all too often proclaims, disingenuously, to be apolitical or merely educational. This may necessitate greater levels of human intervention.

Third, if TikTok is to rely on its hashbank, it must remain abreast of, and endeavour to pre-empt, the sidestepping of moderation procedures. For example, barring the search of certain hashes does not foreclose the ability to adopt flagged names in one’s username, nor does it prevent the search for slight variations on the hash.

Finally, the presence of pro-fascist material raises lingering issues about the algorithmic recommendations applied to users’ ‘For You Page’ (FYP), the centrepiece of TikTok’s vertical content feed. In 2023, TikTok stated that changes in its moderation procedures aimed to prioritise the regulation of violative content based on the severity of harm posed, allowing for a more rapid removal of the most ‘egregious content’. Simultaneously, the viewership of comparatively ‘low-harm content’, of which presumably much of the ‘lawful but awful’ posts discussed herein fall, would be reduced by making them ineligible for display on users’ FYP.

There are two prospective problems here. First, this preventive approach is demonstrably not always applied. TikTok’s algorithm continues to feed users problematic content based on their prior searches and watch history. It was found that this even included posts featuring the aforementioned Rex leader, despite TikTok having already flagged his name in connection with Holocaust denialism.

Second, even after several posts were determined by TikTok to violate its Community Guidelines, the content remained on the platform. Rather than removing the material, it was only at this juncture that such posts ostensibly ceased to be ‘recommended to others’. While TikTok’s Community Guidelines are quite thorough in their coverage of hateful beliefs and ideologies, a policy gap is potentially present. Until as late as May 2024, content that may be made ineligible for FYP was clustered into four categories: behavioural health, sensitive and mature themes, integrity and authenticity, and regulated goods. Importantly, though, the content identified in this Insight fits into none of the above, but rather TikTok’s section dealing with ‘Safety and Civility’, under which ‘hateful behavior, hate speech, or promotion of hateful ideologies’ is expressly prohibited. This should render it ineligible for the platform, not merely users’ FYP. As of May 17, TikTok’s Community Guidelines have been updated to expressly make hateful content ineligible for FYP. While this could be a positive development insofar as it expressly grants moderators greater flexibility in dealing with violative content, it may also lead to cases, such as those mentioned above, where moderators err towards the less severe of two options: ineligibility rather than removal.

Kye Allen is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford. His dissertation explores the history of Anglophone fascist international thought during the twentieth century.