Introduction

In a GNET Insight from November 2023, Jonathan Sarwono identified the presence of an extreme right TikTok community based in Southeast Asia (SEA) that actively produces propaganda through memes seeking to promote the racial superiority of Austronesians, an ethnolinguistic group which includes large populations in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, among other places. According to Sarwono, this community, primarily consisting of users from Maritime Southeast Asia, draws inspiration from the aesthetics and narratives of the Western extreme right meme subculture, adapting them to fit the region’s socio-cultural and political milieu.

This Insight builds upon Sarwono’s research by analysing how the Western extreme right meme subculture influences users from Maritime and Mainland Southeast Asia in promoting ethno-religious supremacy. It aims to (1) identify direct Western extreme right influences on the Southeast Asian extreme right community; (2) investigate efforts to localise Western extreme right meme culture by incorporating regional symbols, lexicon, and historical narratives; and (3) examine instances where users deviate from the stereotypical extreme right profile, instead expressing sympathies towards other ideologies across the extremist spectrum.

Background

Recent studies have highlighted that a significant portion of extremist and hate speech content stems from the Western extreme right. However, it is important to note that Southeast Asian users are not immune to such content, primarily due to structural issues like recommendation algorithms. For example, TikTok’s algorithm tends to suggest hateful content following engagement with a single post and recommends content based on geographical proximity. This poses challenges, especially when such online communities are active within Southeast Asia.

As early as 2021, analyst Munira Mustaffa identified various types of SEA-based extreme right online communities on mainstream social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, and encrypted platforms such as Telegram and Discord. These communities ranged from “politically conservative nationalist actors” to supporters of “pan-Asian movements.” Two key points should be emphasised from her findings. First, Nazi and fascist ideologies have historically existed in Southeast Asia. Second, despite variations in specific beliefs, these communities consistently articulate ethno-religious aspirations, frequently pushing for establishing a ‘pure’ homeland either nationally or regionally.

From Hitler to Atomwaffen: Influences from the Western Extreme Right

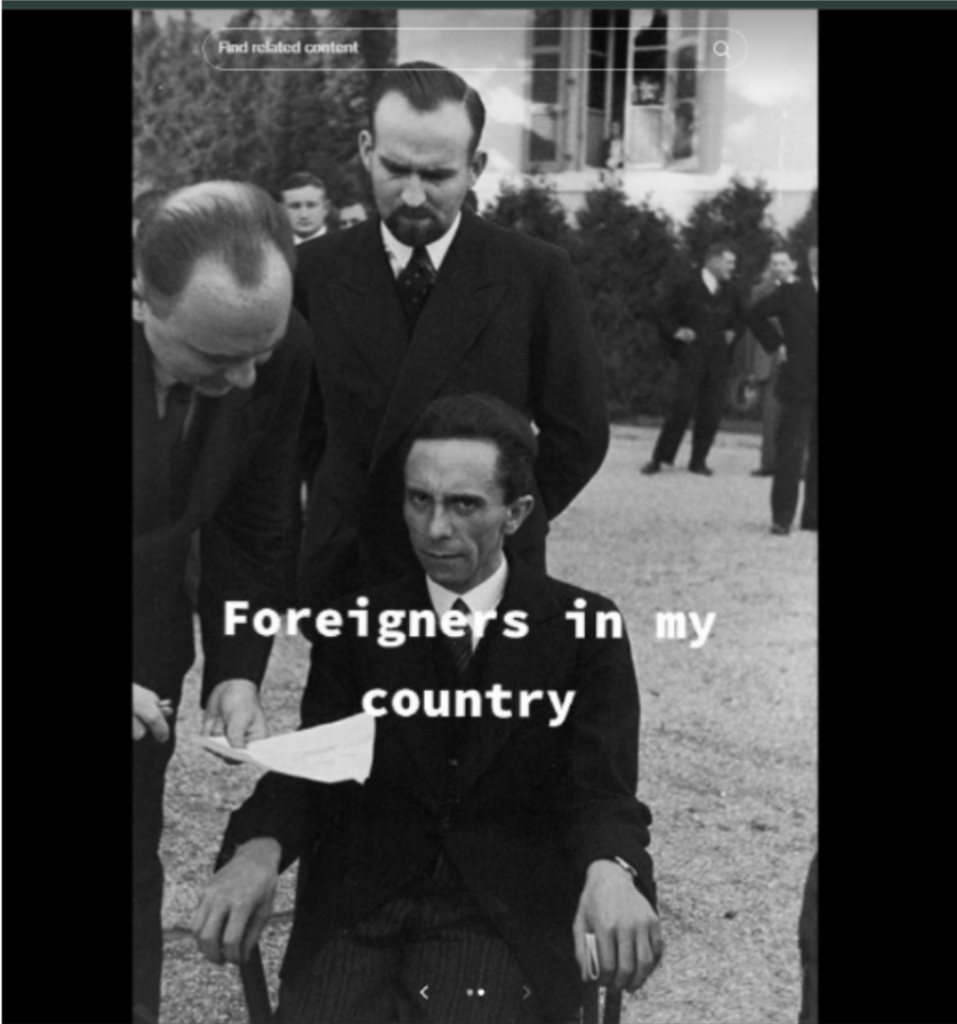

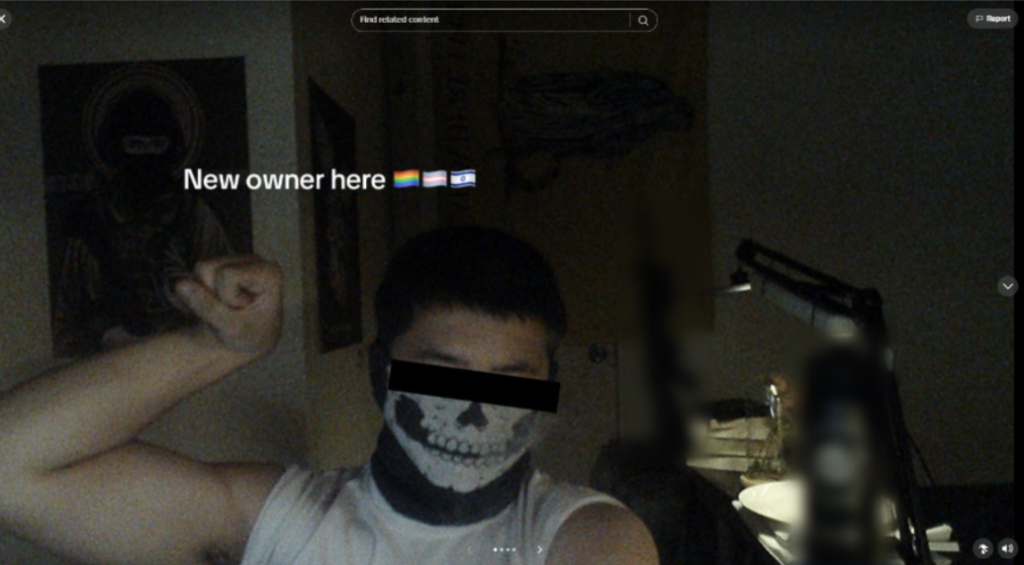

An examination of the Austronesian supremacist TikTok accounts in Maritime SEA unveils content that explicitly includes references to Western extreme right figures and symbols. For example, one self-described “Filipino nationalist” user posted a slideshow featuring the infamous before-and-after picture of Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels upon discovering that his photographer was Jewish. The meme portrays Goebbels transitioning from a smiling expression with the caption “Me having a great day” to a frowning one, accompanied by the caption “Foreigners in my country,” to convey the user’s nativist and xenophobic views (Fig. 1). Other posts include a video with quotes from Adolf Hitler translated into Bahasa Indonesia, a slideshow showcasing and celebrating Third Reich architecture with Hitler’s speech as the background sound, and a user’s selfie wearing the trademark skull mask of the accelerationist neo-Nazi organisation Atomwaffen Division (Fig. 2), among many others.

Fig. 1: Meme of Goebbels on TikTok

Fig. 2: Filipino Nationalist TikTok user posing with a skull mask

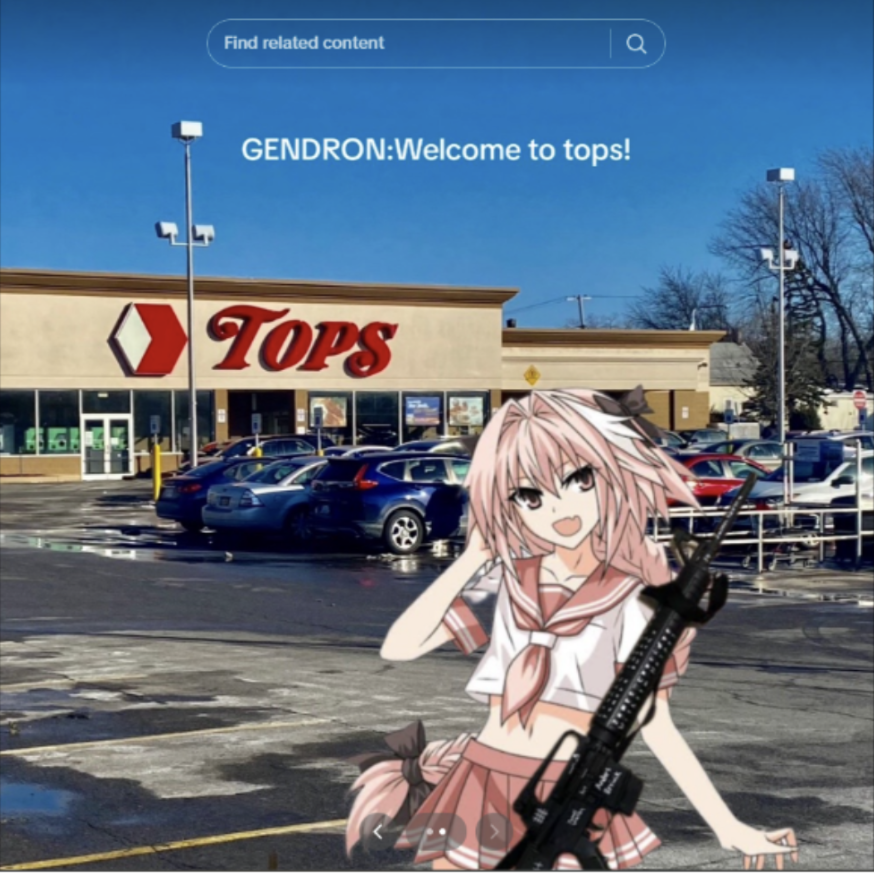

Similar observations can be made about extreme right users in Mainland SEA. For instance, one Myanmarese user posted a snippet of what appears to be a video of Joseph Goebbels’ Total War speech, partially obscured by a Christmas filter, accompanied by the caption “Sweet Kind Heart Man Saying Merry Christmas. How cute”. The video and accompanying caption ironically portray a controversial Nazi historical figure as harmless, reflecting the concerning normalisation of extremist figures and ideologies. Aside from historical references to Nazi Germany, there were also references to contemporary extreme-right figures and incidents. For example, one user from Thailand posted a slideshow featuring a seemingly innocuous picture of a US-based Tops Friendly Markets store on the first slide before displaying an anime character labelled “Gendron” saying “Welcome to Tops!”—a clear reference to the white supremacist shooter Payton Gendron, who carried out the attack in Buffalo, New York in 2022 (Fig 3).

Fig. 3: Anime meme referencing the Buffalo, NY shooting

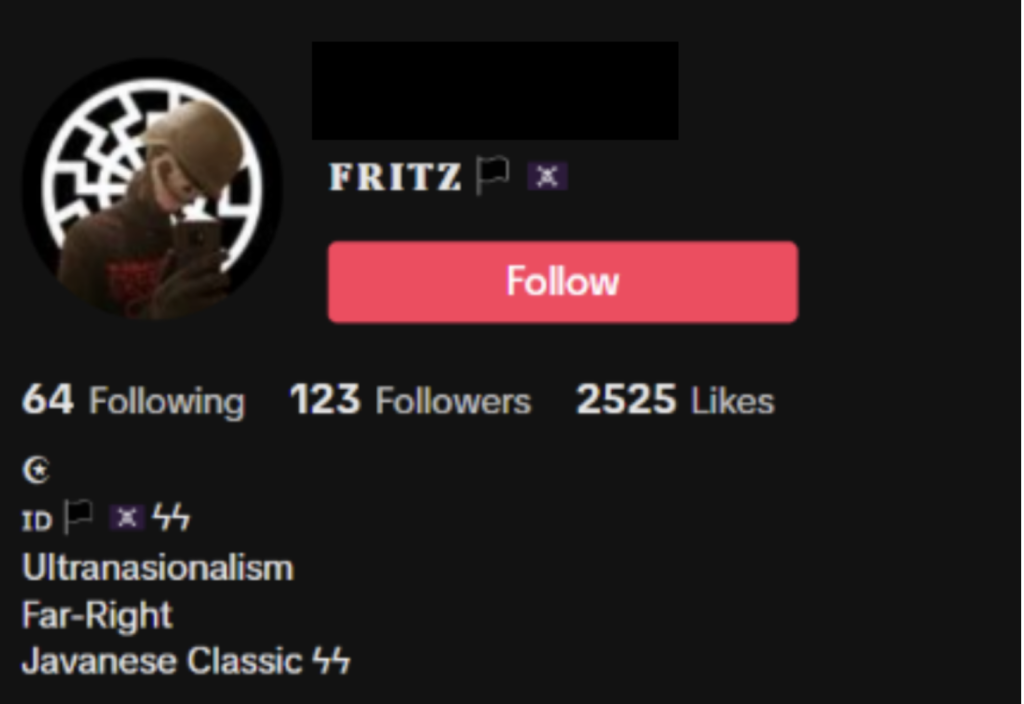

It should be noted, however, that these influences extend beyond the content they create to their display pictures, usernames, and captions. The display picture of one Indonesian user featured an individual adorned German stahlhelm helmet and a skull mask, incorporating the sonnenrad or black sun symbol—frequently associated with neo-Nazis and white supremacists—as the background (Fig 4). In their bio, the user described themselves as a Javanese supporter of “Ultranationalism” and the “Far-Right,” interspersed with another neo-Nazi symbol, the SS bolts. Several accounts also make reference to Nazi figures such as Paul Hausser and Erwin Rommel or include portions of the neo-Nazi numeric symbols, 1488.

Fig. 4: Javanese TikTok user with the sonnenrand symbol in their bio

Localising Extreme Right Symbols and Narratives

While the mentioned instances highlight the direct appropriation of symbols and figures from the Western extreme right, it is important to recognise that the SEA extreme right community goes beyond mere imitation. Sarwono noted discernible efforts by these users to adopt and modify these elements to fit their local context. For instance, the Austronesian supremacist TikTok community appears to draw inspiration from the Western extreme right’s online meme subculture, specifically trends such as “Yup! Anotha Aryan Classics” and “Save Europe.” These trends propagate white supremacist ideas through memes, blending fascist beliefs and aesthetics to reinterpret history or imagine an ethnically ‘pure’ homeland. A cursory search of the TikTok hashtag “#austronesianclassic” unveils a variety of Austronesian supremacist content, demonstrating a clear influence from both the online Western extreme right meme subculture and the distinct local context.

Symbols and Figures

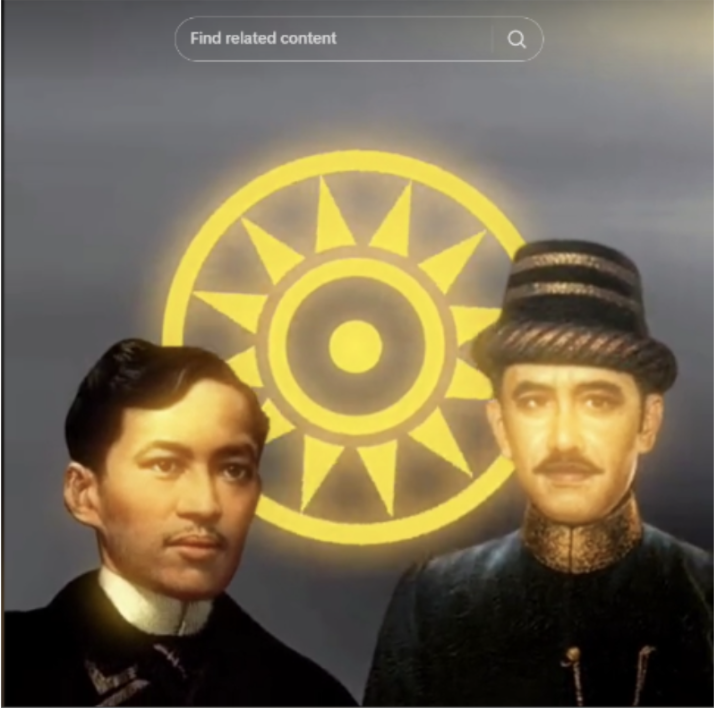

To convey their supremacist beliefs to a local audience, these Austronesian supremacist users frequently integrate historically and/or culturally significant symbols and figures into their content. For example, the previously mentioned sonnenrad is often substituted with other similar yet locally relevant symbols, such as the Surya Majapahit, or the Majapahit sun, emblem (Fig 5) and even the eight-rayed golden sun found on the Philippines flag. Apart from venerating Nazi and white supremacist figures, some users co-opted historical figures from their own heritage whom they perceive as embodying their beliefs. This includes Filipino nationalist and pan-Malayan advocate Jose Rizal and Sultan Iskandar Muda of Aceh (Fig 5). Furthermore, seemingly innocuous regional household items like rice are repurposed as dog whistles; a Filipino user shared a meme of a Filipino man surrounded by rice, along with a Tagalog caption that translates to “6 million? All I can do is 271 thousand,” a subtle reference to the conspiracy theory that the number of Holocaust victims has been exaggerated (Fig 6).

Fig. 5: Austronesian supremacist meme featuring culturally significant symbols and figures

Fig. 6: Filipino meme undermining the Holocaust

Narratives

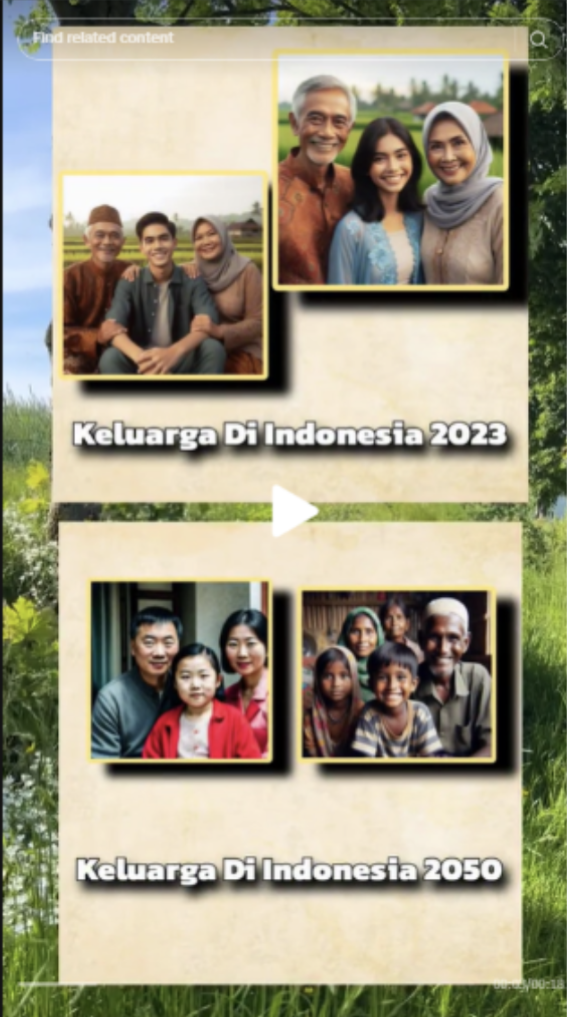

Efforts at localisation also extend to the narratives used in their memes, with the most prominent one centred on anti-immigrant and xenophobic themes. For instance, an Indonesian user reproduced the extreme right ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory, depicting Indonesian families in 2023 as mainly Austronesian and suggesting that by 2050, they will be replaced with what appears to be Rohingyas and Chinese (Fig 7).

Fig. 7: Indonesian Great replacement meme suggesting ethnic replacement by Rohingya and Chinese immigrants

Other memes go as far as to call for violence against these communities. One Indonesian user shared a meme depicting an Austronesian man hammering an Arab and a Chinese with the phrases “Totally Amazing Day” (TAD) and “Totally Cheerful Day” (TCD), which are dog whistles that translate to “Total Arab Deaths” and “Total Chinese Deaths”, respectively (Fig 8). Similarly, another user shared a meme comparing the arrival of Rohingya refugees to the Dutch colonisation of Indonesia, which drew praise from many commenters who wrote, “Totally Refreshing Day” (i.e., Total Rohingya Deaths). These variations are derived from the original term TND (“Total Ni***r Deaths”), which was first popularised by the online Western extreme right community.

Fig. 8: Meme calling for violence against Chinese communities in Indonesia

Localisation in Mainland SEA

Extreme right accounts in Mainland SEA similarly draw influence from the Western extreme right meme subculture in their attempts to propagate ethnic supremacy locally. In an effort to express ultra-nationalist and Islamophobic views, one Myanmarese user posted a slideshow that made use of the Wojak and Yes Chad memes. The first slide shows a Rohingya Muslim Wojack character saying, “We need diversity. Let us in,” while the second slide shows a map of the different ethnic groups of Myanmar with a Myanmarese Chad character saying, “This is enough diversity that we need”.

It’s Complicated: Presence of ‘Salad-Bar’ Ideologies

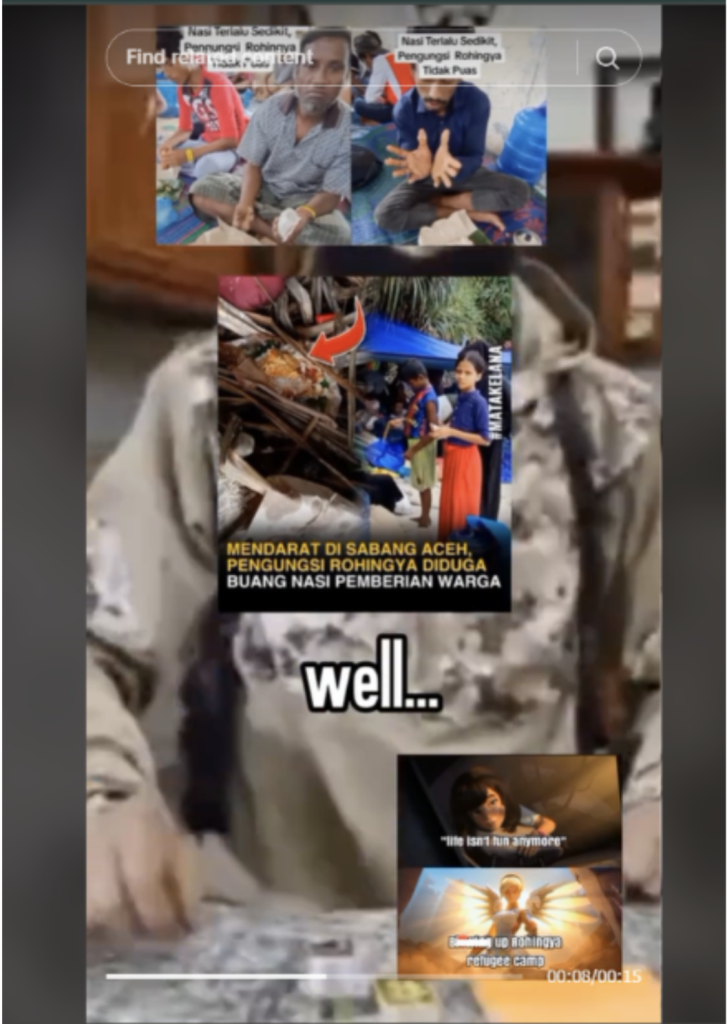

The Insight has demonstrated how the narratives and aesthetics of Western extreme right meme subculture influence an extreme right online community in Southeast Asia. However, it does not suggest that the community is monolithic. There are extreme right users, particularly in Maritime Southeast Asia, who are also sympathetic towards extremist Islamist ideologies. For example, an Indonesian user was observed producing extreme right content, particularly celebrating violent clashes between Indonesian students and Rohingya refugees in December 2023. This was seen in a TikTok post featuring a screenshot of a YouTube feed covering the incident with the caption “TRD confirmed,” followed by the SS bolts. Concurrently, this user has displayed sympathies towards Islamist extremism on their profile. Indeed, the user posted news snippets detailing the conditions of Rohingya refugees, accompanied by an Islamic State (IS) bomb-making tutorial as the video background— not only an explicit call to violence against the refugee community but also revealing their access to IS content (Fig 9).

Fig. 9: A screenshot depicting the conditions of Rohingya refugees, accompanied by an Islamic State (IS) bomb-making tutorial as the video background.

Similarly, a Malaysian user was found valorising Hitler and producing similar anti-Rohingya posts while simultaneously celebrating the actions of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev — one of the perpetrators of the 2013 Boston bombing — as a win. Interestingly, the user appears to express disdain for the Western extreme right in another post, highlighting the higher death toll in the 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombing by IS compared to Brenton Tarrant’s 2019 Christchurch shooting.

These examples shed light on two key aspects of this segment of the community. Firstly, despite their strong opposition to extreme right (Christian) white supremacists, they incorporate Western extreme right aesthetics and narratives into their content. Secondly, they also integrate extremist Islamist visuals and references within these posts to advocate for the ethno-religious supremacy of Austronesian Muslims. This marks a departure from the approach of other extreme right users within the Austronesian supremacist community, who seem to prioritise their national identity in shaping their understanding of Austronesian supremacy.

This contrast was evident in a TikTok meme posted by a self-proclaimed Indonesian “nationalist socialist,” emphasising that differences in colour and creed are not issues in Indonesia, as diversity is part of its cultural heritage. However, the user also suggests that problems arise when Muslims associate their faith solely with being Arab or when Hindus associate their faith solely with being Indian, revealing deeper nativist and ultra-nationalist beliefs.

In short, users from the extreme right online community in Southeast Asia appear to interpret the ethnic supremacy they advocate for differently, influenced by their unique blend or ‘salad bar’ of distinct extremist ideologies that they subscribe to. Such complexity is best described in a meme shared by one Indonesian user. When faced with the statement “I hate your personality,” the user responds with “Which one?” alongside a range of personalities, including Jihadi John, Omar Mateen, Hitler, Goebbels, and Suharto (Fig 10).

Fig. 10: A screenshot from a TikTok depicts a grid of nine men, fictional characters, and real-life terrorists.

Conclusion

While the often-violent rhetoric of the Southeast Asian extreme right community on TikTok might not immediately pose a security threat, the normalisation of such narratives should concern policymakers in the long term. To address these challenges, social media regulators should involve regional analysts familiar with local terminology and symbols when regulating regional forms of extreme right content. This approach can improve effectiveness in combating the spread of extremist narratives and ideologies online. Further research is necessary to fully understand the challenges these online communities pose in both Maritime and Mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in understanding how the emergence of these subgroups is influenced by Western extreme right meme culture or reflects domestic right-wing politics.

Saddiq Basha is a Research Analyst at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research, based at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).