Introduction

In December 2023, a British 22-year-old was sentenced to a minimum of 16 years in prison for planning a gun attack on a Christian preacher at Hyde Park’s Speakers’ Corner, a place renowned in London for attracting religious propagandists and influencers. The planning and organisation of the thwarted jihadist attack appear straightforward, as do the ideological motives behind it. The would-be perpetrator was found to have downloaded al-Qaeda publications and other extremist material and admitted to singling out the preacher for having attacked Islam. Yet, one element of the attack is particularly noteworthy: speaking to authorities, the attacker stated that he intended to wear a camera to livestream the shooting.

In this Insight, I analyse the characteristics and dynamics that make terrorists increasingly choose to record first-person videos of their attacks, allowing an audience to see their violence through their own eyes. After contextualising the rise of this technology, I differentiate between the use of body-worn cameras by terrorist groups and lone actors, indicating the underlying and fundamental differences.

Precedents: Body Cams in War and Terrorist Violence

The presence of wearable cameras in conflict areas is a recent development in the symbiotic existence of visual capture media and war, which began with the first photographs of mid-nineteenth-century battlefields. Although the first models of wearable cameras – or body-worn video (BWV) devices – date back to the mid-1990s, it was the introduction and rapid popularisation of the first digital GoPro models in 2006 that created the conditions for the creation of massive quantities of Point of View (POV) footage capturing violence and conflict. Notable examples of the use of BWV in this period include the 2011 raid that led to the death of Osama bin Laden, which was recorded by helmet cameras worn by the Navy SEALs who carried out the operation. While the raid footage has not been released, other contemporary POV combat videos have attained viral status on social media. In 2012, during Operation Enduring Freedom – the American-led combat mission in Afghanistan – a US Army soldier recorded a gunfight against Taliban militants in the Kunar province from his vest-mounted camera. The three-minute-long footage has, at the time of writing, 47 million views on YouTube, making it one of the most well-known pieces of content from the conflict.

The last decade saw BWV technology become almost ubiquitous in conflict areas, allowing for an unprecedented scale of documentation of ongoing violence. In this context, the technology also found widespread use by terrorist groups. Much of the growth (and later collapse) of ISIS was documented by the devices worn by its combatants. Published by propaganda channels and social media accounts and spread by news outlets and foreign observers, ISIS POV combat videos overlaid with (sometimes) autotuned nasheed chants, invoking war against ‘crusaders’ and ‘disbelievers’ – have captured the collective imaginary. They have gained something close to ‘memetic’ status – attaining, that is, post-contextual recognition and being spread as recognisable memes across discourses and platforms. Other groups of various persuasions and ideological allegiances have also increasingly shared videos captured by body-worn devices. Most recently, vast quantities of POV footage documenting Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel have flooded social media platforms, shaping global political discourse and documenting the group’s atrocities.

Another significant trend in the use of BWV devices by terrorists is exemplified by the rise of ‘lone actors’, such as the Speakers’ Corner jihadist. In 2019, the perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque attack wore a BWV camera, as did the Halle synagogue shooter seven months later and the perpetrator of the 2022 attack in Buffalo, New York. In 2021, the school attacker in Eslöv, Sweden, recorded his stabbing spree using his phone as a makeshift, helmet-mounted BWV device, seeking to directly imitate the Christchurch attack.

Why Do Terrorist Groups Use BWVs?

BWVs can be grouped among other tools for producing user-generated online terrorist propaganda. Factors such as the inherent ‘closeness’ of POV footage, reminiscent of first-person shooter (FPS) video games, and the cheap nature of the medium offer explanations for the popularity of BWV devices. On social media – where content is often uploaded first – these characteristics help it reach a level of virality. POV combat footage from terrorist groups is often immediately recognisable and could be considered a subgenre of war footage in its own right.

Moreover, the fact that the content is almost invariably first uploaded online, only to then ‘trickle down’ to traditional media broadcasters, lends such media an aura of authenticity that relies on the faster pace of online news streams compared to traditional, televised news cycles.

Terrorist groups use BWV devices in calculated ways to advance strategic goals as part of broader, often long-term, propaganda and communication efforts. Their ends include demoralising the enemy, increasing PR reach, inspiring supporters, radicalising target populations, and charging recruitment efforts. This is also clear from the fact that, despite their ostensibly authentic feel, POV combat videos shot by terrorist groups are often heavily edited and adjusted to serve the objectives listed above more efficiently. For instance, it is not uncommon to see Islamist groups heavily ‘videogamify’ their content. Various ISIS media include sounds and visual effects lifted directly from Call of Duty and other FPS franchises – such as ‘hit-markers’ (visual and sound clues that show when the player has shot an enemy), on-screen popups (such as bonus points), Heads-Up Display (HUD) elements (mini-maps, on-screen ‘objectives’ and inventories) and other visual effects (such as the highlighting of targeted enemies).

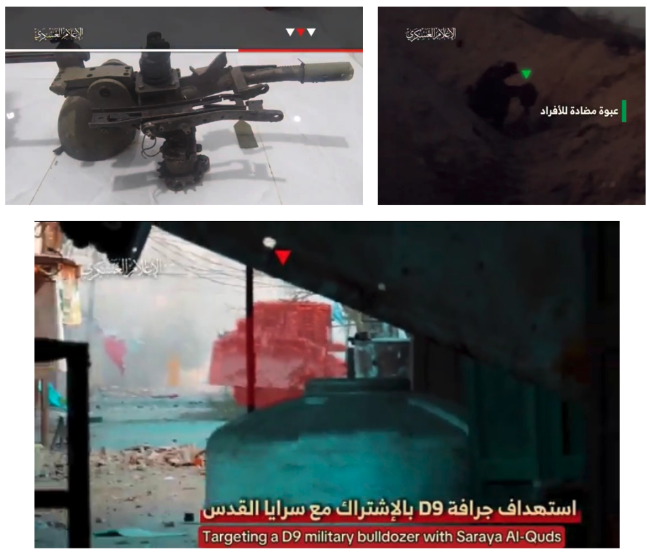

The Red Triangle

A prominent feature in Hamas’s BWV propaganda during the ongoing conflict in Gaza is an inverted red triangle popup indicating Israel Defence Forces (IDF) soldiers and vehicles engaged by fighters (Fig. 1). The symbol has been described in ideological terms, either as a shorthand for the Palestinian flag or as a dog whistle referencing Nazi-era patches sewn on concentration camp detainees to mark political prisoners. However, I suggest it is more correctly interpreted as a direct reference to FPS games, where red downward triangles often denote enemy players onscreen and on mini-maps. Upside-down red triangles are often shown alongside other video game-like elements in post-October 7 Hamas propaganda: downward green triangles signal friendly forces (as in FPS games like Battlefield), and IDF vehicles are often highlighted in bright red when targeted by RPG-wielding fighters (as in Fallout). A few videos even end with a ‘loading screen’, where images of weapons and ammunition are shown alongside a ‘loading bar’, foreshadowing future ‘missions’.

Fig. 1: A collection of screenshots of videos shared on X by Hamas-affiliated accounts and sympathisers, showing certain videogame-like features, such as green and red inverted triangles (denoting friends or foes), the highlighting of enemy targets, and a pre-mission ‘loading screen’ (top left).

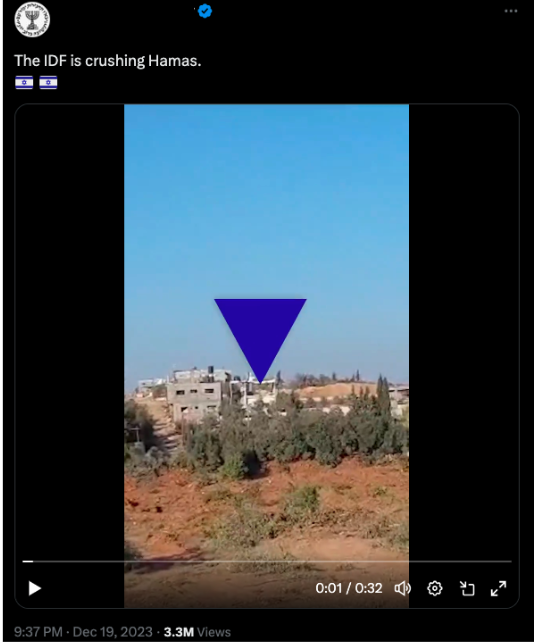

If this interpretation is accurate, the strategic aspects of Hamas’s BWV media and its relation to the gamification of terrorism become clear. Using video game-related symbols and the POV camera perspective, Hamas seeks to reach a mostly online, male, young to middle-aged audience. The widespread knowledge of the symbols discussed above, which do not have a specific linguistic or cultural connotation and are instantly recognisable to FPS players, allows the videos to attain memetic and viral potential internationally. Indeed, such has been the prevalence and attraction of the inverted red triangle on social networks after October 7 that IDF-affiliated and pro-Israeli accounts have increasingly promoted their own POV footage propaganda, this time featuring a blue inverted triangle to denote Hamas targets, in a somewhat awkward attempt at achieving a parallel virality in online discourse (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: An attempt by a pro-Israel account at appropriating the red triangle symbol on social media. It is notable that, in a way, this choice divorces the inverted triangle from its FPS-related context, therefore completely altering its fundamental appeal as a memetic sign, which partly justifies the failure of the blue triangle at equating the impact of its red counterpart.

The Role and Meaning of BWVs for Lone Actors

I argue that there is an important difference in the significance of BWVs for lone-actor terrorists compared to organised terror groups. In the latter case, media produced through body-worn cameras must be primarily considered from a strategic perspective akin to other propaganda. In contrast, the former has a more foundational function connected to the nature of contemporary stochastic, lone-actor terrorism. Various dimensions can be used to justify this claim. Here, I cover two: the individual nature of lone-actor terrorism and its live component.

Individuality: One-Man Band

The first dimension might seem self-explanatory, but it has important implications for the logic of media produced by lone terrorists. Independent from any overarching organisation, lone actors cannot produce media within the same context of long-term messaging campaigns or specific narrative-building efforts. Simply put, they get one chance at creating a piece of BWV content, and as their post-attack chances of survival are minimal, they cannot hope to control its reception.

Likewise, they are responsible for producing and spreading their own content. Regardless of its perceived authenticity, a POV combat video created by a terrorist group is, like other propaganda, the outcome of a vertically structured production process. A bare-bones view of this process sees at least three different steps requiring a hierarchical division of labour: the video is shot by a combatant, edited by another, and then shared by other affiliates on various media channels. Meanwhile, lone actors are simultaneously videographers, editors, and broadcasters.

Content Creators: Livestreaming Hell

This leads to the second component that sets lone-actor BWV media apart from that created by terrorist groups. As lone actors expect not to survive their attacks (or at least not to avoid arrest), the only way they can ensure the spread of their media is to livestream it, creating an interesting coinciding of entertainment and violence. While it is not necessarily wrong to say that combat footage can be considered a form of entertainment, in the case of lone actors, the functions of combatant and entertainer overlap. The Christchurch shooter and Eslöv school attacker both referenced the memetic slogan ‘Subscribe to Pewdiepie’ around the time of the campaign to maintain the Swedish YouTuber’s position as the world’s most subscribed channel. Using this otherwise unrelated slogan signifies the attackers’ self-awareness as content creators and shows that they consider the act of recording videos to be essentially the same as their ‘civilian’ counterparts.

Despite their content, videos from Christchurch, Buffalo and Eslöv are more similar to online vlogs than terrorist propaganda. With this point, I also seek to dialogue with an argument featured in another GNET Insight by Sam Andrews, which argues that visual similarity alone cannot support the gamification argument because POV terror videos lack the ‘interaction’ element of video games. My conception of lone actors as entertainers posits instead that POV videos are not meant to provide audiences with the same interactive experience as video games, but rather, with the more passive experience of viewing a gaming vlog. In other words, POV videos feel and function like watching someone else play a video game.

Conclusion: So What?

BWVs play an important but distinct role in terrorist attacks perpetrated by ‘traditional’ terrorist groups and lone-actor attackers. For the former, BWV footage mainly serves as a propaganda tool. BWVs are more fundamental for the latter, as they contribute to shaping the meaning of their violence by clearly assigning it a performative dimension and aesthetic. Understanding media showing lone-actor terrorist violence as ‘entertainment’ is a controversial position to take. Still, this frame is particularly useful to understand how such media products come to be meaningful to perpetrators and why they choose, with increasing consistency, to create them.

The Hyde Park case illustrates how lone actors of different ideological persuasions are equally drawn to the appeal of BWV technology. An analysis aimed at combating this form of terrorism should, therefore, look beyond ideology and other traditional dimensions and rather embrace more complex questions. For instance, the fact that lone-actor terrorists can be considered content creators who contribute to generating a brand of entertainment that is not fundamentally dissimilar from other online content in the way that it is uploaded, shared, and consumed should make us rethink the political realities favoured by social media.

Policymakers can also benefit from this Insight. Starting from the understanding that the creation and consumption of online material is an economic activity that responds to specific structural and algorithmic characteristics and incentives of social media, this perspective on live-streamed ‘terror-as-entertainment’ shows its deep links with the architecture of popular online spaces. Tackling the spread of hatred and terror online, therefore, cannot be limited to the ideological sphere. Rather, policymakers should increasingly seek to collaborate with private actors, firstly social media operators, to bring meaningful reforms to alter the mechanisms that create openings for the rise of ‘viral’ terrorist media online in the first place.

Manfredi Pozzoli is a master’s graduate in International Affairs at LSE and SciencesPo Paris, as well as a research fellow at Think Tank Trinità dei Monti, in Rome, and an analyst at the Nicholas Spykman Center for Geopolitical Analysis. His research interests include the intersection of social media and terrorism, especially in the context of Europe and North America, and the development of covert psychological operations in the Cold War.