Introduction

In the 1990s, debates raged about whether first-person shooter (FPS) games could cause violence. Following the 1999 Columbine shooting, politicians and the media linked popular FPS games like DOOM with antisocial and violent behaviours. While there is still no evidence for this, today we are witnessing a resurgence in interest in links between FPS games and violence. Even though there are significant gaps in our knowledge, counterterrorism police and security agencies have begun to express worry that FPS games and the communities surrounding them are fertile ground for terrorist recruitment and that the perceived violent themes of these games attract persons with a profile that is vulnerable to radicalisation.

This interest has grown further in the wake of the 2019 Christchurch attack. The attacker made reference to popular gaming figures and streamed the attack on Facebook using a helmet-mounted camera, producing propaganda with a first-person view. This event in particular galvanised further research into the links between gaming and extremism, with some researchers pointing to a special link between first-person propaganda (FPP), FPS games, and video gaming audiences.

Lakhani and Wiedlitzka (2022), for instance, argue that the livestreamed Christchurch attack “gave the feel…of an FPS”, and posit that the similarity is purposeful in order to better drive engagement with extreme ideologies. Comparable positions are adopted by others, including Macklin (2019) and Schlegel (2021). However, while the idea that the Christchurch attack, and the Buffalo and Halle attacks that followed in 2022, were purposefully orchestrated to look like an FPS has gained traction, the theoretical and evidential basis for such claims warrants further scrutiny. Likewise, the linked thesis that the style of the videos produced by the Christchurch, Buffalo, and Halle attacks produces game-like interactions (ie. that they are gamified) needs further exploration.

In The ‘First Person Shooter’ Perspective: A Different View on First Person Shooters, Gamification, and First Person Terrorist Propaganda I argue against the posited links between FPP and FPS. Instead, I argue that 1) FPP does not look like an FPS game; 2) interaction with this media is not akin to an interaction with a video game; 3) the choice of the first-person shot in FPP is more likely a technical choice than one that rests on a desire to look like an FPS and 4) that this calls in to question many of the arguments that FPP is gamified. This Insight summarises these arguments.

On Visual Similarity

One of the core arguments linking FPP and FPS is the visual similarity that stems from the use of ‘helmetcams’. Typically, in FPS games, the player can also see the hands and weapon of the character, and occasionally other body parts, such as the torso and feet when looking down. Both media use a perspective that gives the audience a view ‘through the eyes’ of the game character or person. Galloway (2004) calls this the “grammar” of the FPS – the combination of “a subjective camera perspective, coupled with a weapon in the foreground”. The similarities when comparing images produced from the Christchurch, Halle or Buffalo attacks to some FPS titles can be quite stark.

This apparent similarity is due to the commercial success of FPS games series such as Call of Duty, one of the most popular FPS titles to date. Games like Call of Duty pride themselves on realistic depictions of warfare, hiring military consultants to ensure that the battles depicted are as visually true-to-life as the limitations of video gaming allows. Such games form their own sub-genre of ‘military-sim’ or ‘arcade-realism’, and mostly draw on a wider culture of pro-war militarism that emerged following 9/11. These games do indeed look like first-person terrorist propaganda, as they generally follow a realistic and militaristic aesthetic and emphasise violence.

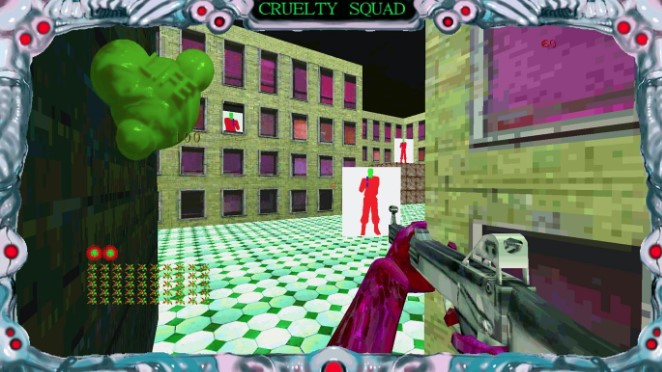

However, the success of Call of Duty masks the diversity of the genre, which also includes games that emphasise puzzle solving, exploration, or stealth instead of violence, and can use cartoonish, abstract visuals. The genre is replete with examples of games which disrupt Galloway’s grammar and that experiment with and explore the limits of the genre. Titles like Cruelty Squad and Neon White do not seek to be realistic, instead revelling in visual styles which actively court difference (Fig 1 & 2). Such games demonstrate that one of the joys of gaming can be the exploration of ideas and possibilities which do not seek to be realistic, but instead are imaginative, and their success shows that gaming audiences have as much an appetite for the abstract as they do for the realistic. More importantly, games like Neon White and Cruelty Squad do not look like Call of Duty, nor do they look like FPP.

Fig. 1: Neon White (2022)

Fig. 2: Cruelty Squad (2021)

Drawing a straight line between FPS and FPP collapses a medium into only those parts which are most hegemonic. As Järvinen (2002) argues, “game genre equals hybridity, because game genres are complex sums of interaction and rule mechanisms, audiovisual styles, and popular fiction genre conventions”. We should not be reductionist in our analyses and ignore the necessarily hybrid and evolving nature of the medium. While some FPS games do share a visual similarity with FPP, this does not mean that there is an immediate relationship. Rather, they have similar objectives – to bring the viewer as close to real life as possible with the limitations of technology. Some FPS look like FPP because they have invested vast sums of money in appearing as realistic as can be achieved. If our only linking of FPP and FPS is an aesthetic similarity, then we must acknowledge how limited that link is.

Exploring Other Possibilities

There are also other reasons why we should reject the explanation that FPP and FPS have a relationship due to visual similarity. The footage itself is not just limited in its aesthetic similarity to FPS; it is also not like a game at all.

In the first instance, video games require interactivity. This is the primary difference between video games and other electronic media. Without an element of play, the footage is fundamentally lacking in any ‘game’ element. Without play, there is also little difference between the footage produced by the Christchurch attack and films which utilise first-person camera shots. This is commonly found in science fiction films like Terminator and Predator, alongside horror films like Psycho, which use the first-person ‘killer viewpoint’ to simulate the horror of being watched and stalked. These shots fundamentally highlight alienation; while we temporarily inhabit the bodies of characters in these films and see ‘through their eyes’, we cannot control their actions. Video games, on the other hand, highlight connection, allowing us to control our avatars.

The difference between first-person views in video games and in cinema rests on this locus of control. As Fiske (2006) argues, “games are played with the body, and excess of concentration produces a loss of self, of the socially constructed subject and its social relations”. In film, we do not have this bodily connection between the avatar and the viewer, resulting in a break in identification. Research by Trepte and Reinecke (2010) further supports the different effects of the two mediums, noting that the psychological effects of watching media can be emotional or cognitive, while the effects of gaming are also embodied.

While FPP might remind us of popular video game franchises, the effect of viewing is not ‘game-like’. This is not to say that viewers will not identify with the perpetrators, however, those that identify with the footage already likely identify with the killer’s ideology, and are not ‘played’ into doing so. Even if the visual similarity between FPS and FPP were absolute, it would still lack that behavioural aspect of interaction and the bodily aspect of immersion that Fiske describes. For this reason, FPP, despite the visual similarity to a video game, is still video media.

The production of FPP footage is also much more likely to be a result of primarily practical, technological concerns than it is to be a result of an attempt to ape video game aesthetics. Helmetcams have already proven their use in capturing extreme sports and combat footage. The most popular camera, the GoPro, is designed to be fixed to a helmet and much footage produced by this camera is clearly captured this way. The cameras also produce social footage; a history of sharing helmetcam footage is embedded in the cultures that designed and adopted the technology. Thus, the technology comes pre-prepared as something which is focused on social sharing and propagation.

There are also practical reasons for choosing a head-mounted position when using a helmetcam. Research by Suss et al. (2018) points out that mounting in other positions such as the shoulder or the chest can easily obscure footage. The head-mounted position is the least likely to be obscured, and the most likely to be pointed in the correct direction.

These arguments call into question whether such footage is gamified simply by our immediate association between first-person cameras and FPS. Visual similarity is, however, not the only association with video games that has caused some to analyse FPP as a form of gamification. During and following these attacks, some users comment on ‘high scores’ or ‘kill-death ratios’ of shooters, drawing comparisons with video gaming. The Halle attacker listed ‘Achievements’ for his attack, drawing a more direct comparison with similar objectives found in many video games.

However, while this references video games, it does not necessarily indicate a purposeful aping of video gaming for the explicit purpose of speaking to a video gaming audience. As Kupper et al. (2022) note, 7 out of 10 attackers in their study attempted to livestream their attack, and borrowed elements from previous significant attacks, indicating a copycat effect as much as any thoughtful attempt to appeal to video game cultures. Likewise, the imageboards and online forums which celebrate terrorist attacks and draw up high-score lists are – as with wider online cultures – steeped in the cultural knowledge that has come with video games now being ubiquitous.

As with referencing other cultural products, referencing gaming could easily be users signalling their knowledge or applying known cultural frameworks to social events. These forums are also well known for employing ironic and dark humour, and might just as easily create high-score lists to signal their misanthropy as they would to genuinely be trying to gamify attacks. Importantly, there is little indication that these users are creating a game when they comment on FPP, and very little evidence that anyone is ‘playing’.

Moving Forward

At the moment, all we know is that FPP might look like certain, specific, games. To go beyond this is to apply a framework of analysis based on speculation and aesthetics. Even with this, the aesthetic comparison is, in my view, weak. The real danger we face here is not just being wrong about a shared relationship between FPP and FPS, but stigmatising a community and drawing the security and surveillance apparatus of the state into a place it does not belong and is likely to do damage. Indeed The European Union Counter-Terrorism Coordinator (2020) has already argued that the predominant player base of games involving violence and war is young, potentially isolated or disenfranchised men, whose psychological profiles could make them prone to radicalisation.

Many other security agencies are also increasingly interested in gaming communities. It is therefore imperative that the research we produce on the relationship between gaming, extremism and terrorism is robust. While there might be a relationship between FPS and terrorist propaganda – and indeed, some terrorist and extremist groups have purposefully developed such games – our current framework of analysis is lacking. While research is still in its infancy, it is important that robust frameworks for analysis are developed and that we critique our initial assumptions. More evidence will emerge as further research is completed, but as we move forward, we must ensure that the foundation of this research is conceptually solid.