Rachel Kowert and Elizabeth D. Kilmer are members of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN). The EGRN works together to uncover how malign actors exploit gaming, to build resilience in gaming communities to online harms, and to discover new ways to use gaming for good.

They work with Take This, a mental health advocacy organisation with a focus on the game industry and community. They provide resources, training, and support to individuals and companies that help the gaming community improve its mental well-being and resilience.

Content warning: This insight contains references to child sexual exploitation and violence

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on improving the safety of internet users of all ages, including in online gaming spaces (game-focused chat servers, forums, and games themselves). Concerns around hate, harassment, radicalisation to violent extremism, and child sexual exploitation (CSE) are all important topics in this conversation. Some scholars have identified similarities between a subset of radicalisation to violent extremism (RVE) processes and grooming for CSE. Though RVE and CSE grooming and processes can happen in a variety of online and offline spaces, greater awareness of these risks in gaming spaces in particular is important due to the ways in which many games facilitate relationship building with limited moderation.

The subset of individuals being intentionally recruited and groomed towards RVE can be effectively viewed as ‘grooming for violence’. The term ‘grooming for violence’ is used here to refer to individuals who have been targeted by an individual or group who work to build trust and a relationship with the goal of radicalisation to violence or to support violence. Broader discussions of the commonalities between grooming for violence and grooming for sexual exploitation may be especially valuable when working with game industry partners to improve the safety of gaming spaces for all users. Though the outcomes of these grooming processes differ, the process of and vulnerabilities to such exploitation significantly overlap. Recent research identifying child involvement in RVE underscores the importance of addressing this issue. Understanding similarities in grooming pathways may support prevention efforts, as well as re-centre players being groomed for violence as individuals deserving of support, as opposed to incorrect assumptions that they have consented to the process. This Insight will outline the commonalities between grooming for violence and radicalisation, emphasising processes relevant to gaming spaces.

Understanding the Overlap in Grooming for Violence and Grooming for Sexual Exploitation

Before we begin, it is important to clarify what we are referring to when discussing grooming for child exploitation and grooming for violent extremism. Grooming for child sexual exploitation is typically defined as a process in which perpetrators build trust and a relationship with a child over time to prepare them for sexual abuse or sexual exploitation. In this process, the children being exploited are often treated as clear victims who need to be protected from exploitation by adults with nefarious intent.

Most definitions of radicalisation to violent extremism generally include the concept of an individual’s development and engagement with increasingly radical content over time, leading them to endorse or engage in politically motivated acts of violence. The process is not always linear, nor is there a single process for radicalisation. Further, not all individuals in an RVE process are children being intentionally groomed and exploited by an individual or group. However, to ignore this subset of targeted and groomed individuals is problematic – children being groomed for violence are also victims who need protection from exploitation by adults with nefarious intent. Failing to recognise this is particularly problematic when discussing strategies for prevention and support for individuals being groomed for violence.

In the following section, we will illustrate similarities in the processes of grooming for sexual exploitation and violence, including target selection, perpetrator similarities, and the process of grooming itself. Though there is no single process of grooming, whether it is for sexual exploitation or violent extremism, there are meaningful overlaps in both risk factors for individuals as well as the grooming process. These are discussed in more detail below.

Vulnerability Similarities

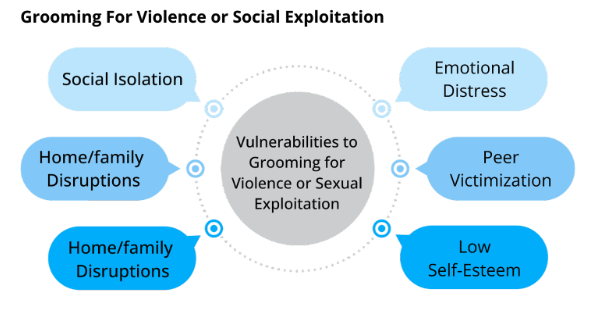

Fig. 1: Vulnerabilities shared between targets of grooming for violence or sexual exploitation.

Similar personal and environmental characteristics can leave individuals more vulnerable than their peers to grooming for sexual exploitation or radicalisation. Environmental vulnerabilities include poor social networks, social isolation, peer victimisation, and poor connections with family. Further, the relative anonymity and lack of moderation in many online spaces are an additional vulnerability. Personal vulnerabilities can include low self-esteem and emotional distress. These vulnerabilities alone are not enough to predict an individual’s likelihood of being groomed for violence or sexual exploitation, nor are they the only risk factors commonly associated with either. For example, perceived in-group superiority and perceived in-group threat are risk factors for radicalisation to violent extremism, but there is no research tying them to grooming for child sexual exploitation at this time.

Perpetrator Similarities

Perpetrators of grooming for violence and sexual exploitation are often perceived as charismatic and well-liked within the communities they inhabit, which may support their efforts in making targets feel special and important in the early stages of the grooming process. Though some perpetrators may be well-liked, research has suggested others face social isolation and rejection in broader social networks and have a history of poor interpersonal relationships. Similar to grooming targets, there is no specific constellation of traits or experiences that can be used to reliably determine who will perpetrate.

Process Similarities

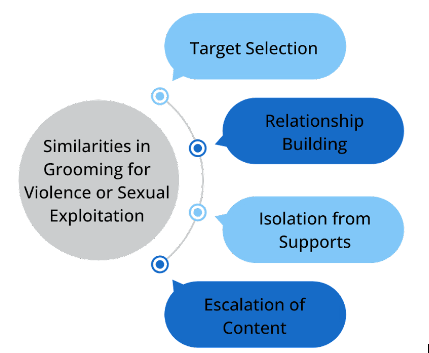

Fig. 2: Process similarities in grooming for violence or sexual exploitation.

Target Selection

Grooming for sexual exploitation and grooming for violence starts with the identification of a target or group of target individuals. Targets are typically chosen based on their availability, ease of access, and individual preferences the perpetrator has. To illustrate how target selection can start in a gaming space, the basics of a team-based multiplayer game can be considered. In many such multiplayer games, players are matched in a team for an activity. Games like this allow players to meet many other individuals and start any potential relationship with a shared experience and teamwork. Those who identify shared likes and dislikes or otherwise enjoy each other’s company can choose to continue playing together. This setup allows individuals low-stakes opportunities to make new friends and opportunities for perpetrators to identify potential targets. Perpetrators may start with several targets if some are not a good fit or reject the perpetrator’s efforts.

Relationship Building

Early in communication with the perpetrator, targets are engaged in relationship-building opportunities, and often the perpetrator works to make the target feel special and validated. Playing online games together can support the development of relationships, and the anonymity of these spaces can help to shield the perpetrator’s true identity from the target if needed.

Secrecy and Isolation from Supports

When building the relationship, the perpetrator may seek to isolate the target from existing supports further and move their communication to more private channels. Perpetrators often encourage the target to keep their relationship or the content they share a secret through cajoling or threats.

Escalation of Content

Over time, the perpetrator will provide and/or solicit more explicit or extreme content with the target, and the relationship itself may include more overt themes of coercion and control. The length of time and speed of escalation differ widely by case, from days to months.

Detection Challenges

In both grooming and radicalisation processes, the initial interactions between target and perpetrator are typically designed to be positive. Additionally, there may not be any sexually explicit or overtly extremist content shared in the initial phases of relationship building (especially in public spaces). As such, common moderation and detection strategies involving explicit keywords or phrases may fail to detect early-stage grooming interactions. Further, because of these factors and the likelihood for perpetrators to choose socially isolated and disconnected targets, their targets may not recognise the perpetrator’s behaviour as dangerous or problematic. Fear of negative consequences from the perpetrator, caregivers, or law enforcement can lower the likelihood of children reporting these experiences. The combination of these factors leads to significant challenges in detecting grooming behaviour in the early stages.

Key Caveats

This Insight is intended to increase awareness regarding similarities that exist between grooming for violence and grooming for sexual exploitation to support the development of effective prevention and mitigation strategies in gaming spaces. In addition to similarities between these processes, there are important differences, such as certain vulnerability and risk factors and manipulation tactics utilised by perpetrators. Processes related to grooming and radicalisation are complex and context-dependent, and strategies to address these issues should be mindful of the complexity and limits of current research.

Much of the research on grooming for sexual exploitation or violence (and radicalisation to violent extremism broadly) relies on the use of small sample sizes and case studies. It is important not to overgeneralise whole populations inappropriately; when such generalisations happen, it can infringe on the human rights of historically marginalised groups through detection strategies that disproportionately (and inaccurately) target individuals of such groups. Policies and tools designed to reduce the presence of grooming for sexual exploitation or violence must keep in mind the well-being of targets of grooming in addition to the larger community to avoid compounding harm.

Conclusions

Improving the safety of our online spaces, especially the gaming spaces occupied by youth, is necessary in our increasingly online society. Understanding the vulnerabilities and processes that lead to real-world harm is key to supporting this aim. Viewing youth being groomed for violence as needing similar care, respect, and support to those being groomed for sexual exploitation will support the development of more effective, person-centred strategies to improve the safety of our online spaces.

Gaming and tech companies interested in supporting online child safety and improving their moderation policies should consider increasing CSE and RVE-specific training of their moderation and community management teams and consulting with experts to support the development of detection and diversion programs. Further, companies should examine their games’ community for norms that may make it easy for perpetrators to hide and groom potential targets. The normalisation of hate and harassment in many gaming communities may make it easier for perpetrators to operate undetected. Developing effective detection and mitigation strategies will require a multidisciplinary approach, including developers, researchers, and other subject-matter experts and stakeholders.