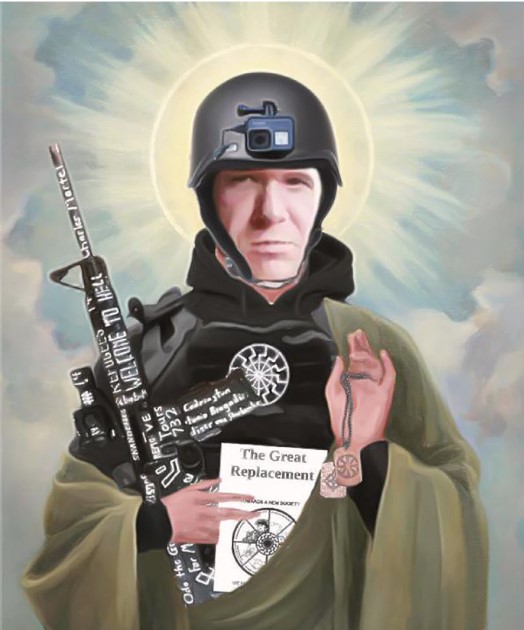

In the aftermath of the March 2019 Christchurch attack in New Zealand, shooter Brenton Tarrant was quickly ‘sainted’ by militant accelerationist subcultures online, who depicted him in visual propaganda as a Christian saint in the style of a religious painting (Fig.1). Since then, a collection of so-called ‘Saints’ has expanded, as the community has anointed other far-right terrorists as ‘Saints’, bestowing upon each new attacker a quasi-religious character. This deification is deliberate; it is meant to encourage further attacks by glorifying terrorist violence and sanctifying its perpetrators as martyrs – whether they are living or dead. Today, this ‘Saints Culture’ has emerged as a prominent vector for radicalisation and mobilisation to violence within the militant accelerationist ecosystem.

Fig.1: Brenton Tarrant depicted as a Christian saint

This Insight will analyse the phenomenon of Saints Culture, examining its evolution and situating it within the context of the broader milieu of militant accelerationist subcultures. In doing so, it will examine the lineage of these Saints and assess their significance as drivers of both online radicalisation and offline violence within online communities that promote militant accelerationism and the glorification of violence.

Origins of Saints Culture

Within extreme right subcultures, deification – being turned divine, either wittingly or unwittingly – by others is not a new phenomenon. Within extreme right subcultures, this practice has always been prevalent. The Nazis constructed martyrs out of figures like Albert Leo Schlageter, who was executed by the French in 1923 for sabotage or, most famously, Horst Wessel, a Nazi activist reportedly killed by communists in 1930. Both men became posthumous heroes of the Third Reich through ritualised commemoration.

Contemporary Saints Culture has its roots in this historical tradition but owes its more immediate origin to the cultic turn of national socialism by its remaining adherents in the 1960s. Savitri Devi, a Greco-French national socialist, began to argue in the 1950s that Adolf Hitler was in fact an avatar for Vishnu, the Hindu God who would bring an end to the Kali Yuga, the dark age of Hindu thought. Most national socialists did not worship Hitler as the actual reincarnation of God, however. The veneration of figures such as Robert ‘Bob’ Matthews, leader of The Order, a US-based white supremacist group, who was killed in a shootout with the FBI in 1984, was a more typical example of how an embryonic Saints Culture began to emerge within extreme right milieus. Matthews was celebrated by figures like William Pierce, leader of the National Alliance and author of ‘The Turner Diaries’ as the gold standard of militancy.

The immediate origins of Saints Culture can be traced to James Mason’s veneration of a plethora of racist killers, including Joseph Paul Franklin, many of whom he praised because he either knew them personally or admired the carnage they created. These killers whose names littered the pages of his newsletter Siege (1980-1986) were re-remembered when his writings, collected in the early 1990s, were digitised and disseminated to a new generation of extreme right activists from 2017 onwards in what became known as ‘Siege Culture’. Many of these figures – together with others drawn from a broader pantheon of school shooters, serial killers, terrorists and authoritarian leaders – were eulogised through the visual culture of the burgeoning accelerationist milieu.

Ideological Evolution of Saints Culture

The use of religious terms to reference neo-Nazi terrorists, whilst already evident during the 1980s, became central to Siege Culture, with Atomwaffen Division referencing Ted Kaczynski, Timothy McVeigh and Anders Breivik as their “holy trinity”. In parallel, the incel community also began referring to mass murderers as Saints around the same time. However, the referencing of terrorists as Saints began after the March 2019 Christchurch attack, with perpetrator Brenton Tarrant immediately elevated to ‘Saint Tarrant’. Subsequent far-right terrorist shootings in August in El Paso and in Halle that October led to additional attackers being similarly glorified. Extremists accompanied the veneration of new shooters with a retroactive anointment of pre-2019 far-right terrorists, such as Robert Bowers, who carried out the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, and the 2011 Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik.

As the Saints ecosystem coalesced around a unified vision for accelerationist violence, a broader pantheon of saints was gradually constructed. One of the primary drivers of Saints Culture is the Terrorgram community, a loosely connected network of Telegram channels and accounts that adhere to and promote militant accelerationism. By 2020, a list naming a total of 50 Saints first circulated on Telegram, featuring the addition of historical white supremacists, including James Earl Ray, the assassin of Martin Luther King, as well as far-right terrorists from the 1990s like the Olympic Park bomber Eric Rudolph and London nail bomber David Copeland. Notably, the list also named individuals with no clear connections to white supremacy, including cult leader Jim Jones, suggesting a fascination with violence itself also played a role in the selection of at least some killers as saints.

The Saints Calendar: Terrorist Attack Dates as Markers for Commemoration

The concept of militant accelerationist ‘Sainthood’ became more formalised in 2021, following the launch of Telegram channels devoted to Saints. These channels published monthly calendars celebrating the dates of far-right attacks and marked other milestones including the arrests, deaths and even birthdays of perpetrators. Propagandists also produced fact sheet graphics that broke down the details of each attack into easily readable paragraphs alongside the death toll and the number of wounded, attack method and status of each killer alongside a montage of their photos, pictures of their weapons victims and crime scenes. These graphics, which resemble collectable trading cards, are known as ‘Saints Cards’.

The highly-networked nature of Telegram facilitates Saint commemoration across Terrorgram, as Saint Cards are forwarded throughout the network on the anniversaries of attacks. Each card includes a ‘further reading’ section that directs users to manifestos, articles or documentaries so followers can educate themselves about each attacker and their crimes. The reappearance of links to additional crime scene photos or websites like ‘Murderpedia’ highlights how Terrorgram grafts a macabre fascination with violence and death to broadcasting a rolling curriculum.

The calendar-style promotion of Saints further ritualises the glorification, which aims to inspire future attackers with a steady stream of examples of Saints with high ‘scores’ to be beaten. In addition, some admins of channels have encouraged members to celebrate the anniversary of attacks by editing and sharing new visual propaganda glorifying attackers, illustrating the interaction between important dates and the participatory media culture of Terrorgram. As highlighted by Winkler et.al in their date-based analysis of extremist groups for GNET, symbolically significant dates can strengthen the collective identity of a group and provide important cues for audience members to reinforce beliefs and model their behaviours. The Saint calendar marks dates important for Terrorgram identity formation, inspires continued content creation and promotes future violence.

Terrorgram propagandists have devoted substantial resources to glorifying Saints. Last year, Terrorgram released the first major video production with a 24-minute-long documentary, ‘White Terror’, which celebrated 105 terrorists and killers they deemed to have acted for the cause of white supremacy. In the film, a ‘fashwave’ music track accompanied an edited montage of scenes from movies, CCTV and archival news footage while a female narrator detailed the crimes of Saints from 1968 to 2021 (although not all of those mentioned were known white supremacists). In addition, Terrorgram’s 261-page Hard Reset publication, a PDF zine promoting militant accelerationist tactics, referenced Saint Cards when calling for further attacks and hinted at the future publication of a ‘Saint Encyclopedia’. While the encyclopedia has yet to be released, its appearance along with the White Terror documentary and devoted Telegram channels highlights the centrality of Saints Culture as a core pillar of the Terrorgram subculture and propaganda efforts.

Real-World Violence and Saints Culture

In the case of the May 2022 supermarket attack in Buffalo, New York, it was the 2019 Christchurch Mosque attack that caused the Buffalo perpetrator, Peyton Gendron, to realise that “hope is not over, that our replacement can be overturned.” His embrace of antisemitic and white supremacist narratives such as the Great Replacement theory was crystallised by his single-minded fixation with Christchurch attacker Brenton Tarrant. Gendron’s personal idolisation of Tarrant would become evident in both the text of his manifesto and the execution of his attack, highlighting the multifaceted inspirational role of Saints in creating the next mass shooter. Analysis of his manifesto shows that 67% of Gendron’s document is identical to Tarrant’s manifesto, with significant sections focusing on ideology found to have been plagiarised directly from the Christchurch shooter. Like Tarrant, Gendron used a body camera to livestream his attack and ensured his manifesto and diary-style chat log were appropriately disseminated across receptive online communities. For both of these actors, these steps were crucial in both telegraphing their ideological alignment with the neo-fascist landscape as well as leaving behind a blueprint for the next Saint to follow.

This ‘propaganda by the deed’ approach observed in Gendron’s attack is also evident in the case of Juraj Krajčík, who shot two individuals and injured a third outside an LGBTQ+ bar in Bratislava, Slovakia in October 2022. Krajčík, much like Gendron, found motivation not only in localised conspiracies and extreme right narratives within Slovakia but also within the pantheon of Saints, namely Brenton Tarrant and Poway Synagogue shooter, John Earnest. Pertinently, analysis by the Accelerationism Research Consortium highlights not just the copycat effect of the actions of these two Saints, but the “contagion reaction” of Gendron’s May 2022 attack. According to this analysis, Gendron’s attack served as the direct inspiration, the “final nudge” for Krajčík to begin to seriously pursue a mass casualty attack in the name of Saints Culture and Terrorgram.

Krajčík’s attack also served as a unique instance of direct appeals to the Terrorgram network by one of the Saints. Krajčík used his manifesto to direct readers to Terrorgram publications Militant Accelerationism and The Hard Reset, and specifically addressed Terrorgram in his “Special thanks” section, in which he stated “You know who you are. Thank you for your incredible writing and art, for your political texts; for your practical guides. Building the future of the White revolution, one publication at a time.” Krajčík’s adulation of Terrorgram was well-received by the collective, which rapidly added him to the pantheon of Saints, anointing him as “Terrorgram’s first Saint”, and disseminating content which praised and honoured him.

Looking Ahead

As detailed within this Insight, the evolution of the Terrorgram community centred around a neo-fascist identity and the embrace of Saints Culture has been a central driver for radicalisation and mobilisation within the militant accelerationist milieu. The Terrorgram network provides a focused ecosystem for digital organising and community-building on Telegram, while the dualistic mobilising elements of Terrorgram propaganda and calls to action by Saints such as Brenton Tarrant and Peyton Gendron have created the conditions for a lone-actor pipeline of accelerationist actors to emerge from this ecosystem.

Copycat attacks, as well as attack elements inspired by previous Saints, are a central feature of the accelerationist Terrorgram network and Saints Culture. For these actors, preserving a record of their pathway to violence and sharing instructional material are often just as crucial as the attack itself. This trend is observed in Gendron’s pre-attack writings, which included a “guide of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) on how to carry out mass shootings to any potential future mass shooter.”

The glorification of Saints is likely to remain a core pillar of the Terrorgram subculture, as indicated by its propagandists devoting significant resources to producing Saints Culture content. As outlined above, this has encompassed both the glorification of each new killer and the historical revision of previously forgotten or more obscure attackers, to help construct a ‘lore’ of white terror. And, as further demonstrated by the repeated references in Krajčík’s manifesto, the concept of Sainthood within online communities like Terrorgram is likely to continue to serve as a mobilising concept for lone actors and provide powerful symbols for future terrorists.

This Insight’s findings align with the conclusions reached by Winkler et.al in their recent report for GNET, which highlights the need to incorporate date-based analysis into our understanding of extremist groups and movements. Given the prevalence of Saints Culture and the accompanying calendars which glorify and memorialise the dates of significant attacks and other events in this milieu, it is crucial that tech companies incorporate symbolically important dates into their algorithms for detecting harmful content online. As outlined in this Insight, symbolically important Saints Culture figures and their actions play an outsized role in community-building and inspiring violence. Therefore, future efforts to counter the growth of these movements require a nuanced and in-depth understanding of patterns of behaviour in digital extremist subcultures.

Joshua Farrell-Molloy is a Research Fellow with the Accelerationism Research Consortium. He holds an MA in Security, Intelligence and Strategic Studies from the University of Glasgow and his research focuses on the far-right, online extremist subcultures and foreign fighters.

Jon Lewis is a Research Fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, where he studies domestic violent extremism and homegrown violent extremism, with a specialization in the evolution of white supremacist and anti-government movements in the United States and federal responses to the threat. He is also the Director of Policy Research at the Accelerationism Research Consortium

Graham Macklin is a researcher at the Norwegian Center for Holocaust and Minority Studies affiliated to the Center for Research on Extremism (C-Rex), University of Oslo, Norway. He has long-standing research interests in fascist and extreme right-wing politics in Britain, North America and Europe and is interested more broadly in studying political violence and terrorism. He is the author of ‘Failed Führers: A History of Britain’s Extreme Right’ (2020).