Joshua Farrell Molloy is a research fellow of the Accelerationism Research Consortium (ARC). ARC is dedicated to a collaborative, empirical approach to understanding and addressing the threat of accelerationism to democratic societies. For more information on ARC’s research, please visit their website.

Introduction

The far-right accelerationist ‘Terrorgram’ network on Telegram is a neo-Nazi subculture centred on promoting white supremacist terrorism and connected to at least one deadly terrorist attack and two arrests in Europe. Terrorgram encourages violence by calling for attacks, glorifying far-right terrorists, and distributing instructional guides on bombmaking or infrastructural sabotage.

The most distinct characteristic of the subculture is its unique visual style which plays a major role in its strategy of glorifying militancy and terrorism. Sharp and visually appealing aesthetics define the Terrorgram brand and build subcultural cohesion. Their in-group formation is developed through the fetishisation of the terrorist image in propaganda and ‘terrorwave’ – a visual style in which the aesthetics of the militant are worshipped. This Insight will briefly explore the importance of the aesthetics of violence in this community and how it has been incorporated into both calls for violence and real-world terrorism.

Terrorwave

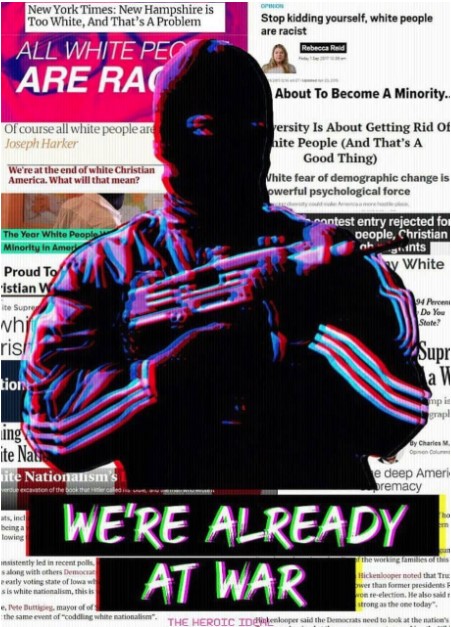

Edited ‘terrorwave’ graphics depicting militants in conflict or post-collapse environments first emerged on 4chan around 2018 but have persisted as a common style on Terrorgram. Journalist Jake Hanrahan has described terrorwave as removing “the reality of the violence war brings” while revealing how “bored young men in the West desire a violent past they’ve no perception of.” Content is often altered with a glitchy VHS-style effect to make it resemble old film footage, or with neon colour grading, emitting a sense of nostalgia (Fig.1). Militants and scenes from decades-old conflicts in Northern Ireland, Chechnya or the Balkans are regularly repurposed for accelerationist propaganda, while images from contemporary conflicts are often edited with VHS degradation to appear older.

Fig. 1: An iconic image of a Provisional IRA gunman repurposed for militant accelerationist propaganda.

The focus of these images is on what is perceived to be an attractive ‘fashionable’ style, rather than the ideological affiliations of militants. Graphics and art can include jihadists, criminals, leftist guerrillas or paramilitaries, with a common theme often being the appearance of a balaclava or mask. The Provisional Irish Republican Army’s distinct 1990s era urban guerrilla chic is particularly popular across Terrorgram and Siege culture, with images of masked IRA gunmen frequently used as templates for propaganda and edited to feature far-right symbols or slogans.

Terrorgram’s celebration of terrorism and militancy aesthetics distinguishes it from the broader far-right ecosystem, attracting those most drawn to violence. This feature has been noted as valuable by community members, with one channel admin declaring “you would achieve a lot more” with just “100 fanatics” [who supported militant accelerationism], as opposed to “10,000 weekend warriors.” Although few of those active within a “lethal subculture” will ever engage in violence, participants contribute to efforts to inspire future attackers through disseminating content glorifying terrorist action and collectively cultivating terrorism as a ‘style’.

The terrorist image beyond digital propaganda

Voices within the accelerationist milieu have explicitly engaged with the concept of the idealised terrorist image. Mike Ma, an influential figure and author of the accelerationist novel ‘Harassment Architecture’, has argued the difference between terrorists and killers who achieve iconic status and those who do not “depends on how well they were dressed”, singling out and praising the Columbine shooters and ISIS for their ability to ‘look good’.

Likewise, in ‘Hard Reset’, a Terrorgram zine promoting terrorist tactics, future attackers were urged to consider optics, stating: “The day is coming where your face is gonna be on the news in the form of a mugshot or an obituary. If you’re still fat or greasy that’s gonna be a huge problem”. The section suggested readers think about how they will look on “CNN”, their “Wikipedia article” or future “Saint Card” (the quasi-religious depiction of far-right terrorists as ‘Saints’), encouraging potential attackers to incorporate aspects of aesthetics into fantasies of and plans for violence.

Indeed, considerations for physical appearances already surface during terrorist attacks. The 2022 Buffalo shooter claimed in his manifesto the tactical gloves he wore during his attack were chosen for aesthetic reasons, stating that if “you aren’t trying to look cool, what the f**k are you even doing?” The same shooter also exhibited other symbols with deep meaning, decorating his rifle with white supremacist slogans and wearing ‘black sun’ patches on his plate carrier, drawing inspiration from the “cultural script” of the 2019 Christchurch mosque attacker before him, who displayed similar iconography.

Conclusion

Grafton Tanner writes, in our era across internet culture, “outdated styles are constantly being repackaged, reimagined and re-tooled to sate present thirsts”. This theme also presents itself in extremist propaganda, with Terrorwave imagery depicting a nostalgic dreamscape characterised by a wistful longing for an imagined fantasy world of violence. Likewise, in her work on far-right youth culture in Germany Cynthia Miller-Idriss has identified articulations of masculinity made through fashion: the soldier/warrior and the rebel/rule-breaker. Within Terrorgram, similar themes are merged in the idealised terrorist archetype constructed in propaganda, demonstrating how it can also be partly linked to broader far-right traditions.

Mass shooters and terrorists have long dressed up for violence, articulating symbolic meaning-making through their clothing, and visual content indulging in fantasies of violence, such as ‘tacticool aesthetics’, ‘loadout’ visual culture or jihadist digital art praising the militant is visible in other extremist spaces. However, Terrorgram is unique in the extent to which the aesthetics of violence dominates its subcultural cohesion and branding, with the broader visual ecology of the community playing an important role in the collective cultivation of terrorism as a ‘style’.

Much of this type of content is often not clearly branded with extremist logos or slogans, so also easily travels across mainstream platforms. This can make it challenging for tech companies to develop effective policies to counter it. Future platform moderation policies may need to develop a broader contextual understanding of the visual content to identify and categorise this type of material within extremist communities.

Joshua Farrell-Molloy is a Research Fellow with the Accelerationism Research Consortium. He holds an MA in Security, Intelligence and Strategic Studies from the University of Glasgow and his research focuses on the far-right, online extremist subcultures and foreign fighters.