In 2015 one of the key problems for social media platforms was the rise of Islamic State (IS), their supporters crowding spaces such as Twitter, in order to propagandise, recruit and build community. Fast forward to 2020 and the growing problem for social media platforms is the far-right; unlike IS supporters, they are less easily identified and the boundaries between their content and wider social media populations are more blurred.

The Internet provides rich data on online extreme movements, text and images. There is evidence that images are better remembered than words, and they can pack an emotional punch. Yet, as Conway and others have pointed out, academics studying extreme movements online have been slow to adapt theory or methods from other fields. The visual turn has not led to widespread in-depth study of the images posted by IS supporters. Yet images give us key insights about the online experience, and in two regards: identity and community.

In this Insight we draw on a dataset of Islamic State supporter profile pictures (avatar and banner) collated in 2015 with the research network VOX-Pol, to note patterns in image use, and ask, what lessons can be drawn from this data for the study of extremism on social media platforms now?

Lesson 1: Communities conform, but individuality still matters

Our sample consisted of some 80 IS supporters online, a sample small enough to enable an additional full textual analysis of tweets from these accounts. Each account actively identified as an Islamic State supporter at a time of mass migration to territories in Syria and Iraq. Approximately half of this group claimed to be women, half men. They used English as their main language, and were dispersed globally, some claiming to have travelled to Syria or Iraq to join IS, others in Europe, North Africa, or the Americas.

Profile image choices potentially had global resonance, therefore. Despite differences in locations, we found conformity around key themes. IS supporters – men and women – relied on: nature images (animals, landscapes, flowers); IS iconography (flags or logos); religious slogans or images (such as the Quran); and weapons.

However, unique visual identities within those themes were important. New avatars and banners remained consistent in style and tone, enabling users to find one another and projecting continuity in self-presentation. This was particularly important following suspension from Twitter, and an attempt to rebuild profiles after their return to the platform.

Lesson 2: Online behaviour is gendered in meaningful ways

Despite an overall visual conformity, our analysis of the dataset found the majority of pro-IS images organised around gendered division, mirroring gender as a fundamental organisational feature of Islamic State itself.

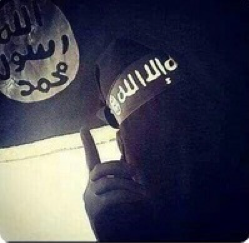

Pro-IS men and women shared visuals emphasising their gendered role, for example, men’s avatars portraying warrior masculinities contrast with the IS femininities – conformity in dress and appearance – women display.

| Avatars | Banners | Avatars | Banners | ||||||

| Theme | No. | Theme | No. | Theme | No. | Theme | No. | ||

| Women | Woman in burqa | 28 | Nature | 24 | Men | IS Fighter | 25 | Nature | 14 |

| Nature | 23 | IS Symbol | 15 | Nature | 10 | IS Symbol | 13 | ||

| IS Symbol | 15 | Religious | 12 | Weapons | 8 | Religious | 9 | ||

| Weapons | 8 | Weapons | 8 | Religious | 7 | IS Fighter | 8 |

Avatar Images from Women’s Accounts

Avatar Images from Men’s Accounts

The sample used avatar images as primary assertions of identity, aspiration and self-image. Unsurprisingly therefore, men’s avatars most frequently displayed male IS fighters and women used images of women wearing burqas, echoing the pride in the burqa emphasised in billboards within Islamic State. In both men and women’s profiles images of nature also featured. The nature code included lions, cats, camels, horses, seascapes, landscapes, the sun and moon. Women also used images of flowers, often roses, associated with the history of the Caliphate.

Banner images provided context to avatars, framing them within a particular visual discourse. Of the banner images, nature scenes were the most prominent for men and women (24 for women, 14 for men), and pointed to the importance of the jihad. A key aspect of the salafi jihad is that it promotes Shariah as God-given, not man-made. Nature scenes point to the beauty both of God’s creation, and Islamic State territory. For women, banners often showed romanticised landscapes of towns within IS territory, echoing sunsets featured in English-language IS propaganda magazines and aimed at women. Women also used lion images to communicate both support for jihad and their relationship with men. Lions and birds sometimes appeared in couples in images. Such images do not just communicate love, but also adherence to Islam, in which marriage to a Muslim is a duty.

Banner Images from Women’s Accounts

Banner Images from Men’s Accounts

Women’s profile pictures did not emphasise motherhood, however, a key aspect of life in Islamic State, and few images showed children. Many women’s kunyas (aliases) do use the honorific ‘Umm’, which means mother. This likely therefore signals single status and a willingness to meet IS men online and forge relationships in order to become IS mothers.

These images therefore tell a gendered story, conforming to and reproducing the key ideology of IS central to the state-building project: the differentiation and complementarity of men’s and women’s roles. Through the use of images, we see how supporters of an extreme ideology understand and represent their roles in ways that are likely to appeal to fellow supporters, both men and women.

Lesson 3: Women support violence

The fact that women support extremist groups still surprises some, despite decades of research. Weapons are featured in eight of the women’s avatar images, and Islamic State symbols in 15. Women’s Twitter profile pictures allowed them to express visual support of IS violence, even while their tweets indicated that they accepted armed jihad is for men alone.

Women’s banner images, complementing the main avatar, again demonstrate the commitment to violence, through the prevalence of IS flags and banners, and weaponry. Complementing images demonstrate the framing of this violence – through both religion, and relationships with male fighters. Religious images such as images of Quranic text, in Arabic and English, feature in more of the banner images (12) than profile pictures (9). There is however only one image of a woman using a weapon, as this is not consistent with the IS doctrine that armed jihad is primarily for men.

Lesson 4: Supporters are part of wider cultural milieus

Mostly the IS Twitter community cohered around IS values and a violent subculture of ‘jihadi-cool’, but some accounts deviated from the norms. Our sample shows a small minority of a total 13 (9 women, 4 men) pro-IS images displaying humour as a form of political jamming, and coherent with alternative forms of jihadi cool, also appealing to a wider youth milieu. These include the use of cartoons to mock Shia and the Iraqi police; playful cartoons portraying IS members as ninjas; joke scenes with animals, such as the ubiquitous IS kitten holding weapons.

Going Forward

For some, Islamic State is old news. The threat it posed was unique, but the lessons that can be drawn from study of the images associated with its online support groups are not. Image analysis provides insight into the projected values of online communities purporting to support extreme groups, and how supporters negotiate individual identities within these. This has implications for prevention. As Khawaja has noted, IS online profile images aided community members to find one another, but also aided Twitter to remove many IS accounts, at least in English. As social media platforms grapple with the more amorphous threats presented by the many different elements of the far-right, it will be more important than ever to analyse the ways groups use images to create identity and community, to distinguish threats from wider ‘noise’. The more we understand extreme cultures and communities online, the better able we are to negotiate and disrupt them.