Recruiter or Adviser?

One of the least understood elements of IS’s use of the Internet is ‘recruitment’.

If much has been written about the role of ‘online recruiters’, their activities are often described schematically and typically pictured as that of abusive men who lure young people to Syria.

Based on interviews we conducted with 80+ IS returnees in French prisons, the reality seems quite different. Some of them have actually participated in full-time ‘recruitment’ activities in different places and cybercafes in northern Syria. One jihadi described his duties as tantamount to ‘advising’ the already convinced and helping motivated European volunteers travel to Syria, rather than persuading fragile people to support IS: “There is no such thing as recruiters, ’cause when you are there (in Syria), you’re always being added on Facebook by people in France who wanna come, they come to me, I don’t have to “fish” them.” This differs from other methods used by on-the-ground recruiters in Europe who are more proactive, and this sort of comment has to be understood as referring to a period where IS controlled a good part of Northern Syria and Iraq (2014–2016).

At this time, IS employed hundreds of Internet contact persons who served as the ‘virtual’ air traffic controllers for convoys of potential volunteers. Present on social networks under pseudonyms and easily accessible to worldwide Internet users, these jihadis represented some kind of IS civil servants and performed from Syria the functions of hijra advisers or IS’s virtual immigration office.

The case of an IS ‘immigration’ adviser

One example among many is a 21-year-old young convert from Wattrelos in northern France, who joined IS just before the summer of 2014, as shown on his accessible virtual profile.

He operated on Ask.fm under the pseudonym of AbaMouslim and was active on it for about a year, from September 2014 to September 2015, until a short impersonal post noted his death. His profile specified he was living in ‘Dar al-Jihad’ (the land of Jihad, i.e. IS) while his picture represented a light shining into the dark, echoing IS symbolic and visual narratives. Ask.fm is an Internet platform particularly popular with teenagers and it follows a simple principle: strangers ask questions visible to everyone on the virtual wall of a given account, and its owner then has to decide whether he/she answers publicly or ignores the message. IS quickly and discreetly made the most of it to get in touch, inform or guide various audiences.

Over the course of a year, an ‘online adviser’ like AbaMouslim replied to 273 public messages. This figure is substantial since an important number of his posts invited the ‘asker’ to switch to a private messaging service (back in 2014 it was Facebook or Twitter; nowadays jihadist militants more commonly use apps such as Telegram, Signal, WhatsApp or even Instagram). Therefore, Ask.fm was used as an online meeting point for sympathisers and ‘advisers’, yet public activity on this platform only represented the tip of the iceberg.

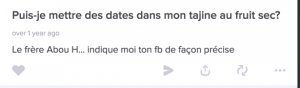

AbaMouslim’s answers take the shape of small arguments, benevolent advice and sometimes discussions with activists. Through the analysis of his account, we discovered that his missions were to: 1) reassure volunteers about the safety of their journey; 2) insist on the feasibility of the trip as long as it is organised in coordination with IS’s men in Syria; 3) inform volunteers about the need to segment their itinerary and to converge in Gaziantep in Turkey, where IS’s logistical support base appeared to be quite active back then; 4) specify that IS smugglers who navigate through Turkey’s border are professionals on the organisation’s payroll; and 5) recount some basic obligations of the Salafi-jihadist creed: it is necessary at all costs to leave the land of impiety (Europe) in order to pledge allegiance (wala) to the IS caliph. According to the Wahhabi principle of al-wala wal bara (allegiance and disavowal), as he put, it is impossible to be Muslim in Europe. The French adviser also used coded formulas, often referring to cooking. In this one for instance, one of his contacts asked: “May I add dates into my dried fruit tajine?” to which AbaMouslim replied “Brother Abou H., give me your precise Facebook account.” Several examples copy this same pattern- such language was probably employed to deliver ‘en route’ information to individuals who were already on their way to the Levant, without triggering social network monitoring algorithms. It also shows IS’s caution, providing (basic) guiding lines for online advisers to stay below the radar.

IS men like AbaMouslim did not ‘recruit’ but rather guided, informed and advised individuals who requested information and who deliberately wished to travel to Iraq or Syria. The link between them did not need to be personal, they just had to identify each other on the networks and speak the same language (which appears to be specific, a sort of Newspeak, of slang French mixed with Salafi-creed references).

The analysis of exchanges between activists in France and their correspondents based in Syria underlines that IS did have support base in Western Europe and that volunteers were not, in most cases, victims of IS propaganda but deliberately trying to join the organisation. Notwithstanding the fact that a minority of people had been ‘lured’ by IS, the vast majority of Europeans who reached Syria were most likely supporting the group. This, in return, highlights the importance of understanding doctrinal change within European Islam over the course of the past 20 years that could explain how 5000 European citizens (80% of them originating from France, the UK, Germany and Belgium) decided to respond positively to IS’s call after it created a so-called jihadi ‘caliphate’ in June 2014.

Understanding this major aspect will help further our understanding of the current ideological reconfiguration that has been happening both online and in real life within Salafi and jihadi circles in Europe and the Middle East.