Introduction

Extremist groups increasingly target ethnic Tajiks for recruitment through sophisticated online propaganda campaigns, resulting in some of the world’s most horrific terrorist attacks over the past year, including those in Kerman, Iran and Moscow, Russia. An ethnic Persian people of central Asia, the largest Tajik populations exist in Afghanistan, where over 11 million comprise more than a quarter of the population, and Tajikistan, where just over 10 million comprise the country’s vast majority. For over a decade, the authoritarian government of Tajikistan and extremist groups in Afghanistan have waged an ideological war for the hearts and minds of Tajik people living on both sides of the border, with terrorist groups, including the Taliban-aligned Jama’at Ansarullah (JA) and the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), recruiting ethnic Tajiks to carry out massive attacks both regionally and globally. This Insight explores the various ways terror groups in the region seek to recruit and co-opt ethnic Tajiks using online propaganda, and possible measures platforms can take to address this growing challenge.

The Tajik Taliban and the Al-Qaeda Media Nexus

In 2021, the Afghan Taliban handed control of the Tajikistan border districts of northeast Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province to JA, an al-Qaeda-affiliated group formed in 2006. For years, JA has maintained a hostile relationship with the Emomali Rahmon authoritarian government in neighbouring Tajikistan, where the group came to prominence following a September 2010 suicide attack on a police station that killed two officers, two civilians, and wounded 28 others. Since then, JA has regularly focused on cross-border operations, including attacks, border raids, and online propaganda aimed at recruiting people within Tajikistan. JA publicly aligned itself with the Afghan Taliban following the latter’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, earning the unofficial title of Tehreek-e-Taliban Tajikistan (TTT). JA’s ideology is primarily a mix of the Taliban’s brand of radical Islamism mixed with Tajik ethno-nationalism.

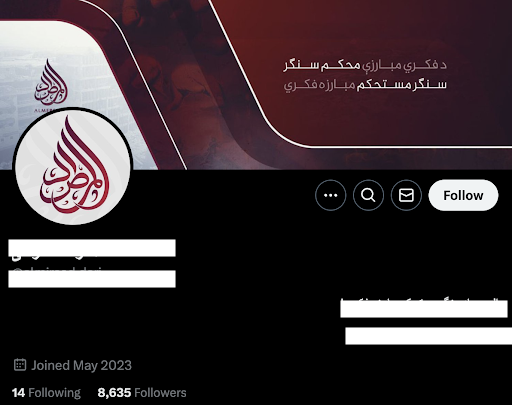

JA maintains an active presence on Telegram. In an October 2021 post on Telegram, Mahdi Arsalan, one of JA’s top leaders, declared his group’s readiness to invade Tajikistan. According to a November report from the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), JA members ‘continue to speak in Telegram channels about continuing Jihadist activity against the government of Emomali Rahman’. The group also benefits from the Taliban’s broader media nexus, including the reportedly Al-Qaeda-operated al-Mersaad media campaign, which produces Tajik language pro-Taliban content that mirrors news coverage on X and Telegram. Al-Mersaad’s coverage includes regular criticism of Tajikistan’s Rahmon government, referring to the president by his Soviet-era name ‘Rahmonov’ and labelling him a ‘communist’. The campaign also blames the Rahmon regime for the rise of its ideological rival, the ISKP, which also runs an extensive propaganda campaign to radicalise ethnic Tajiks on both sides of the border.

ISKP’s Recruitment of Ethnic Tajiks Produces Global Consequences

The ISKP targets and recruits ethnic Tajiks using an extensive online propaganda campaign, recruiting individuals to carry out notable attacks inside Tajikistan as well as launch attacks on the country from neighbouring Afghanistan. The group has also recruited Tajiks for international attacks, with major attacks in Kerman, Iran and Moscow reportedly perpetrated by ethnic Tajiks from Afghanistan and Tajikistan, respectively. On 8 April, Italian police arrested a Tajikistan national with alleged ties to the Islamic State (IS) at Rome’s Fiumicino International Airport. On 14 June, US authorities arrested eight Tajik nationals with alleged ties to IS who had illegally crossed the southern border. According to former US Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia David Sevney, although the total number of Tajiks in the ISKP is ‘fairly small’, they form a ‘fairly large portion of the more aggressive and successful fighters.’

Ideologically, the ISKP shares JA’s criticisms of the Rahmon government but also extensively criticises the Taliban and their affiliated groups for their lack of aggression and ideological purity. In this way, the group targets disaffected members of JA and other extremist groups, such as the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), for recruitment. The ISKP’s al-Azaim Foundation is the largest contributor of propaganda for the group and functions as part of a broader constellation of sixteen other competing but aligned groups that produce translated content in Tajik and several other languages for a global audience. The ISKP even uses AI-generated newscasters to broadcast propaganda via its Khursan TV channel on Teleguard, a Swiss alternative to Telegram.

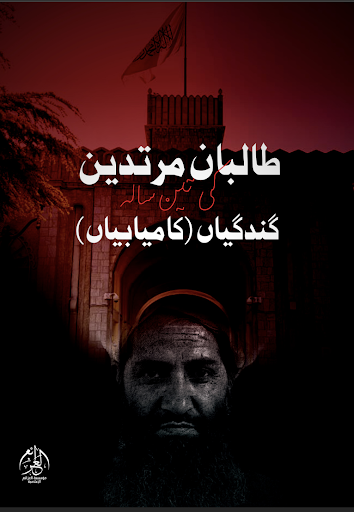

This extensive media ecosystem produces propaganda in the form of online print magazines and videos with narratives focused on criticising both the government of Tajikistan along with the Afghan Taliban and JA. For example, videos produced by these outlets frequently criticise Rahmon’s dictatorial and nepotistic rule, with many featuring faked images of the president’s humiliation and death. The ISKP also focuses much of its propaganda on the Taliban and its affiliated groups. On 24 November, the ISKP’s Voice of Khorasan publication released an issue on RocketChat extensively devoted to criticising the Taliban’s three years of de-facto control over Afghanistan titled ‘Three Years of the Taliban Apostates’ Filth’.

Figure 1: The cover of the 24 November issue of Voice of Khurasan titled ‘Three Years of the Taliban Apostates’ Filth’.

Fertile Ground for Radicalism to Take Hold

Tajikistan’s regular crackdowns on religious freedom and other civil liberties, and a desperate economic situation on both sides of the border, have produced fertile ground for radicalism to take hold among ethnic Tajiks. Since 2009, the Rahmon government has adopted increasingly repressive tactics aimed at curbing extremism, including only permitting state-sanctioned religious activities and widespread surveillance of religious organisations. Measures have also included informal bans on hijabs for women and beards for men, leading to reports of police publicly and forcibly shaving men in some instances. Such repressive measures likely play a role in driving radicalisation in the country. Meanwhile, Tajikistan’s economic situation produces little opportunity for the public, with a recent government report noting that most citizens do not earn enough money to afford basic necessities. Moreover, the economic situation on the Afghan side of the border is even worse, with a 7 March United Nations report noting that Afghanistan’s economy has ‘basically collapsed’. In this way, crackdowns on religious freedom in Tajikistan and a spiralling economic situation on both sides of the border create a situation for extremist propaganda to take hold among disaffected Tajiks living in both countries.

Although Tajikistan’s government has sought to limit the public’s exposure to online extremist content using widespread Internet censorship, these measures have been broad in scope and have not stemmed to presence of extremist content in recent years. Instead, these efforts have served to hide the Tajikistani army’s use of deadly force by shutting down opposition media while indiscriminately cutting off Internet access in some 200,000 people living in the troubled Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (GBAR) for extended periods. Although such measures may limit some exposure to extremist online content at the expense of human rights, the recent involvement of Tajik nationals in terrorist attacks demonstrates extremists’ ability to reach them on both sides of the border effectively.

Figure 2: Al-Mersaad (also spelled Al-Mirsaad, Arabic for The Watchtower) operates openly on X, producing pro-Taliban content in the style of a media outlet. This Dari language account is one of several operated by the campaign, which also operates X accounts in English, Arabic, Uzbek, Russian, and more. The campaign’s slogan is ‘Stronghold for ideological struggle.’

Recommendations

Addressing extremist content aimed at ethnic Tajiks requires a tailored approach, including content moderation in the Tajik and Dari languages, which are mutually intelligible but use different scripts. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) allow for automated content moderation, and these systems should continue to be programmed with advanced Tajik and Dari language capabilities. Although large platforms such as Facebook, X, Instagram, and TikTok have systems to limit extremist content and continue to advance in this area, other platforms such as Telegram and RocketChat are much more limited in their moderation. Apple and Google have successfully pushed Telegram to adopt stricter content moderation policies by threatening to expel it from their app stores. Still, extreme content continues to proliferate on the platform. In this way, further pressure is needed to bring companies like Telegram, Teleguard, RocketChat and others into compliance with best practices regarding content moderation.

The legal basis for limiting the content of the pro-Taliban media channel al-Mersaad, which operates extensively on X and Telegram, is much less clear as the group does not publicly align itself with the Taliban regime or al-Qaeda, which experts believe operates the channel in secret. In this way, further research demonstrating that designated terrorist groups operate al-Mersaad would be invaluable in shutting down the pro-Taliban campaign in the future.