Introduction

Elections in fragile democracies are often the targets of terrorist exploitation. Notably, general elections that took place in Pakistan in February of this year were marred by militant attacks. Months before the polling day, various terrorist groups began espousing and producing anti-election propaganda. The groups used online spaces, such as Telegram and Rocket.Chat, and offline methods, like graffiti and flyering, to disseminate their propaganda to the public. Terrorists also committed violence against political figures and election offices around this time, with the attacks multiplying in the lead-up to election day, making electioneering nearly impossible in the provinces of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Due to the increasing number of attacks and threats of violence on election day, voter turnout declined almost 5%, from 52.1% in 2018 to 47.6% this year.

This Insight analyses the modus operandi of the terrorist groups involved in these activities such as the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF) and more. Mainly, this piece examines their use of multimodal and multilingual propaganda, and acts of terror, such as suicide bombings and assassinations, to influence elections. It concludes with recommendations on how best to counter these democracy-disrupting threats.

Anti-Election Propaganda and Threats

Militant groups in Pakistan began issuing anti-election propaganda when talk of conducting general elections started in mid-2023. They communicated their messages through video statements, graffiti, posters, magazines and booklets. In their propaganda statements, the ISKP, BLA and BLF warned the political parties and citizens against taking part in democratic activities and threatened to strike election targets. Their propaganda was multi-lingual: published in Pashto, Urdu, and Balochi (Fig. 1).

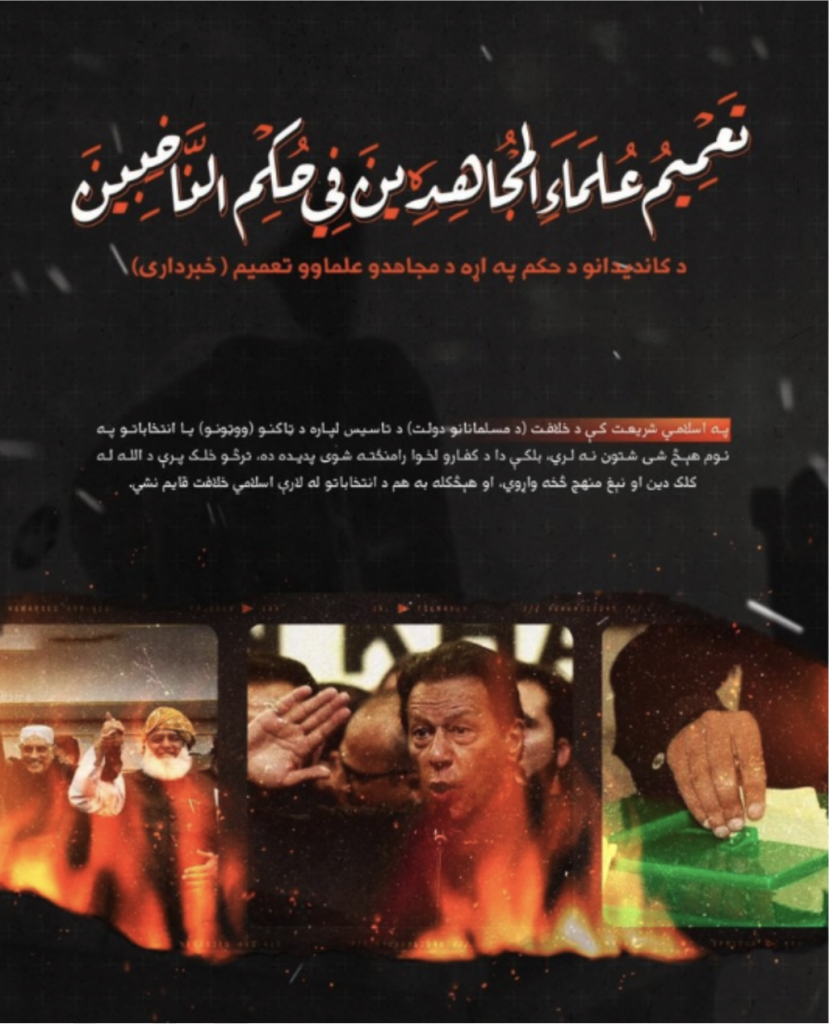

Fig. 1: ISKP’s Al-Azaim media released a Pashto magazine aiming to discredit Pakistan’s general elections.

ISKP, the regional franchise of the Islamic State (ISIS), was the most active in this regard. Its propaganda was specifically aimed at Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Fazl (JUI-F), a religio-political party in Pakistan. However, the group did not limit its propaganda to JUI-F; it warned everyone against participating in democratic activities. ISKP’s animosity towards the JUI-F stems from the latter’s ideological ties with the Afghan Taliban, as both are associated with the Deobandi school of Islam. This ideology is in contrast to ISKP’s Salafi ideology. Moreover, the Afghan Taliban have led several brutal operations against ISKP in Afghanistan and have executed many of its fighters and leaders – reducing the group’s numbers significantly. These factors have turned JUI-F into ISKP’s main target in Pakistan.

The group’s first major issue of anti-election propaganda came in the form of a 27-page booklet titled ‘Proofs of Disbelief in Elections’ published in August 2023 by the group’s media house, Al-Azaim Foundation for Media Productions and Communications. ISKP shared it to various groups on Rocket.Chat. The platform is similar to Slack, enabling jihadist groups to converse with their supporters and disseminate propaganda via servers they control and operate. ISKP’s members also exploit X (formerly Twitter) to bolster their cause, despite the platform’s continuous efforts to remove accounts affiliated with the group.

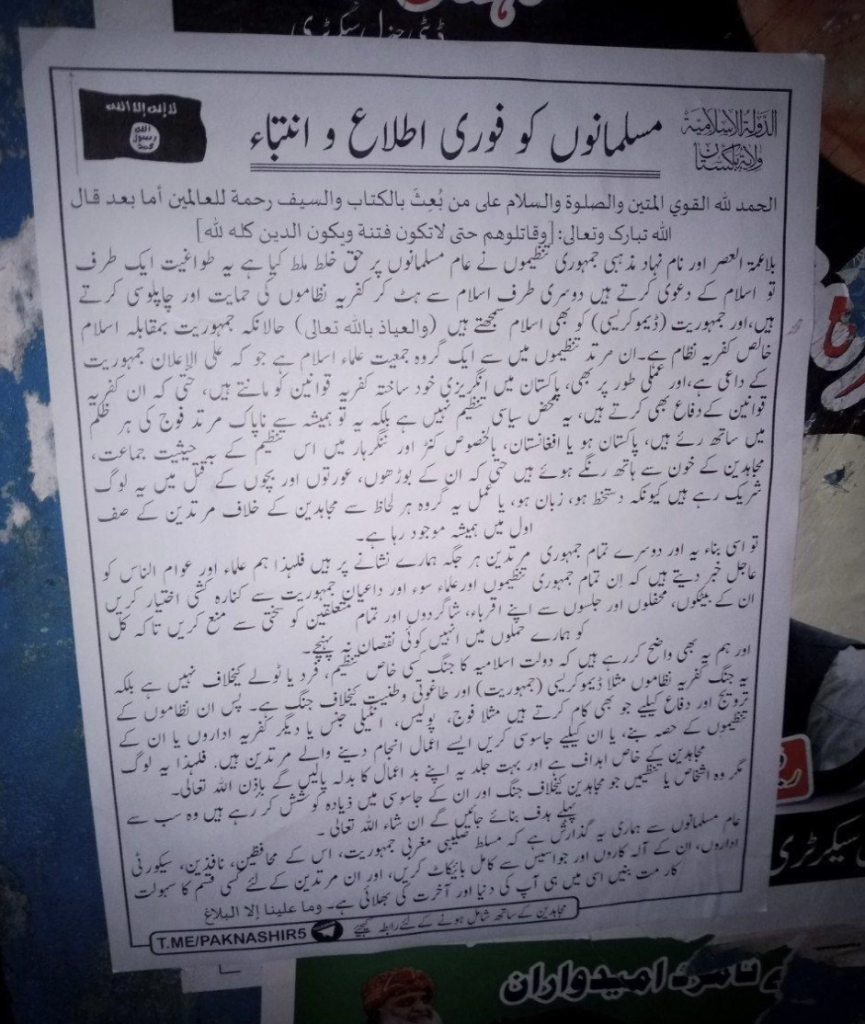

While the ISKP continually issued statements online, members and sympathisers also put posters on walls across cities in Pakistan warning against taking part in elections. Its statements and messages urged citizens to boycott elections and threatened to carry out attacks on election targets (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: ISKP’s poster on a wall in Bajaur tribal district threatening to carry out attacks on election targets.

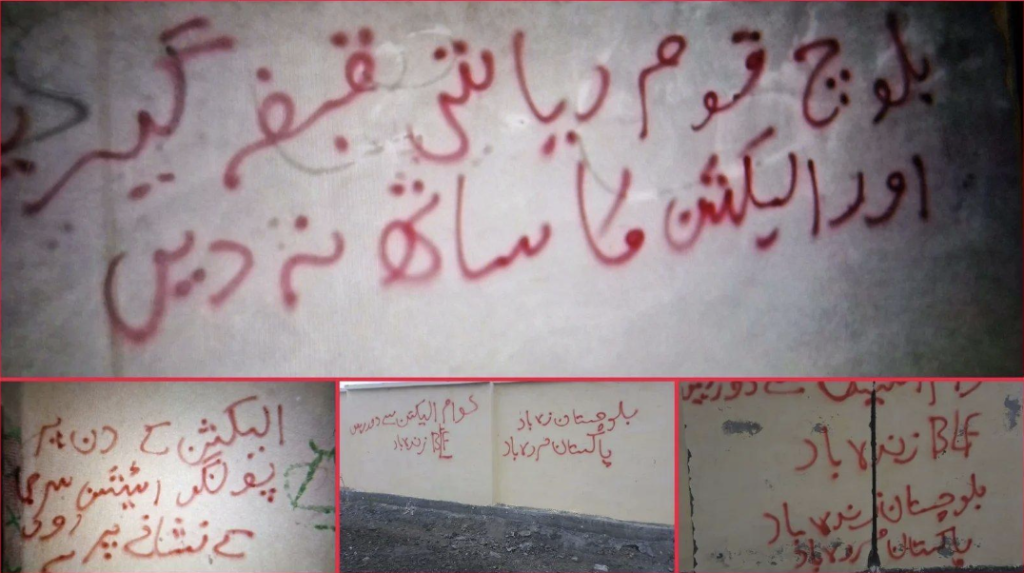

Other groups, such as the BLA and BLF also issued graffitied statements urging people to boycott the elections (Fig. 2). Both the BLA and BLF are separatist groups that seek the separation of Balochistan from Pakistan. Importantly, these groups do not believe in parliamentary politics and are part of the Baloch Raji Ajoi Sanghar (BRAS) alliance. BRAS aims to consolidate the factionalised Baloch separatist movement and orchestrate concerted attacks against Pakistani security forces and Chinese targets, especially on infrastructure projects associated with the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The alliance was formed in 2018 in Balochistan and was announced on a Twitter account.

BLA used Hakkal Media, its media arm, to spread its online propaganda. Hakkal Media used to operate only on Telegram channels but now also uses WhatsApp, with nearly 2,000 followers. This is a concerning development; unlike Telegram, which fewer people in Pakistan use, WhatsApp is used widely and can be accessed on almost every mobile phone in the country, particularly among young people.

Fig. 2: BLF’s graffiti on a wall urging the Baloch people to boycott elections.

Pre-election Terrorist Violence

Similar to the anti-election propaganda, terrorist attacks on electoral targets in Pakistan also ramped up ahead of the elections. Groups like the Islamic State Pakistan Province (ISPP), ISKP, BLA, and BLF intensified their anti-election terrorist operations as the elections drew closer. The first major attack on election-related targets was a suicide bomb blast on 30 July 2023 at JUI-F’s political convention in Bajaur, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. ISKP claimed the attack, which killed 56 people. Most of the JUI-F members have been killed by the ISKP. The party’s senior leader, Hafiz Hamdullah, was attacked twice before the elections, once in September 2023 and then again the day before the election. He survived both attacks.

Other politicians from different political parties were also targeted. For instance, a bomb blast ripped through the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s rally on 30 January in Sibi, Balochistan province – killing 4 and injuring 6 others. The attack was claimed by Islamic State Pakistan Province (ISPP). In another incident, ISKP militants shot and killed an independent candidate and social activist, Rehan Zeb, in Bajaur. As a result, polls were postponed in the slain candidate’s constituency. These attacks were aimed to stop the electoral process, which the ISKP and other jihadist groups believe is un-Islamic.

To create fear on the eve of elections, ISKP bombed two election offices in Balochistan, killing 30 and injuring many others. On the same day, BRAS carried out 20 attacks, mainly on the election campaigns in the province. By creating fear and panic, the terrorist groups aimed to tarnish the elections and thereby upend democracy in the country to achieve their aims, which in the case of ISKP is the establishment of a Caliphate as an alternative form of government in the country and the separation of Balochistan from Pakistan for the Baloch separatists.

The imminent threat of violence in Balochistan on the polling day particularly alarmed the authorities. Of the 5,028 polling stations in Balochistan, only 961 (approximately 19%) were designated as ‘normal’ by the authorities; 2,337 were declared ‘sensitive’, and 1,730 were classified as ‘highly sensitive’ due to the high risk of terrorist violence. Due to widespread insecurity, Balochistan’s interim Information Minister, Jan Achakzai, warned that internet services would be temporarily suspended in areas with polling stations marked as ‘sensitive’ on election day. Social media platforms were considered disruptive, as there were concerns that terrorists would use platforms to heighten their communications on polling day. These concerns were valid as the terrorists normally use the internet and social media platforms mainly for secure communication and planning in Pakistan. However, the internet shutdown failed to prevent terrorist attacks as the BLA carried out 43 attacks on election day across Balochistan.

Election Day Violence and Interference

Despite the interim government suspending mobile services across the country on polling day, terrorist groups carried out 51 attacks, killing 12 and injuring 39. In some areas, militants also took over the polling stations and tampered with the ballot boxes and papers. For instance, the head of Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) in Karachi, Hafiz Naeemur Rehman, called attention to the fact that armed terrorists took control of several polling stations in the presence of police and rangers, causing injuries to JI workers and tampering with election materials. The politician cited instances of fake voting with ballot papers found outside polling stations and armed men occupying polling stations across the city. The leader of the National Democratic Movement, Mohsin Dawar, also alleged that the Taliban took over the polling station in Tappi, North Waziristan district.

Terrorist violence and interference in Pakistan’s elections demonstrate the fragility of this democracy. While the terrorists used basic, mainstream social media platforms to damage the democratic process this time, the situation could escalate significantly when they gain access to emerging, advanced technologies. This would facilitate easier dissemination of propaganda and coordination of attacks, posing a greater threat. In this scenario, they could have even more power and influence over the country’s law enforcement agencies and could interfere more easily in future elections. This scenario is plausible due to the rapid adoption of new technologies by terrorists, creating challenges for counterterrorism authorities in preventing the dissemination of propaganda and the execution of attacks.

Conclusion

For Pakistan to counter terrorists’ influence on their elections, a robust and proactive strategy is required. While militant groups commonly use Telegram for online propaganda, exploiting WhatsApp’s channel feature has added a new dimension to their online propaganda. Although the general public rarely uses Telegram and is largely safe from terrorist propaganda, WhatsApp’s channel feature helps extremist actors bring their propaganda to a far wider audience. As nations like Pakistan find it increasingly hard to battle terrorists’ online propaganda, this new dimension will make it impossible to prevent the terrorist content from reaching the wider public – unless social media companies or instant messaging apps develop further strategies to assist security agencies. WhatsApp should set certain requirements for making channels to prevent the militants from having online space to spread their message. Other communication and social media platforms should also clamp down on terrorists’ online presence and allow accounts and channels only when they are verified as being free of radical content.

Notwithstanding this, there is no effective security infrastructure in Pakistan that could have deterred the militants from targeting elections and politicians on polling day. Therefore, along with a sophisticated counter-propaganda apparatus, Pakistan also needs a robust counterterrorism infrastructure. Only a holistic approach in cooperation with the social media companies will ensure that future elections in the country are secure and free of terrorists’ interference.

Osama Ahmad is an Islamabad-based freelance journalist and researcher. He writes about democracy, human rights, regional security, geopolitics, organized crime, technology, gender disparities, political violence, militancy, conflict and post-conflict, climate change, and ethnic nationalism. His works have been published by The New Humanitarian, The Jamestown Foundation, FairPlanet, South Asian Voices, The Express Tribune, The News on Sunday, and The Friday Times. He tweets at @OsamaAhmad432.