Introduction

This Insight draws on empirical research conducted in two localities in North Macedonia and a discourse analysis of online content. The research was implemented by ELIAMEP’s South-East Europe Programme in the context of the Horizon 2020 PAVE Project. The research identifies the online space, particularly social media, as a key radicalisation risk in the country. Malicious actors leverage the online space and new technologies to effectively disseminate their extremist narratives, posing serious threats to community security and public order.

This Insight examines the role of cyberspace in (de)radicalisation in North Macedonia. It investigates the role of virtual communities as a tool employed by radical groups to attract supporters, analysing both their targeting strategies and the online community’s reactions to their extremist content.

The Use of the Online Space by Extremist Groups

The online space is one important driver of radicalisation in North Macedonia. For jihadist, ethno-nationalist and far-right extremist groups alike, the internet has become the most important tool for communication, mobilisation, and propaganda. The social media strategy implemented by radical groups is granular in nature; every piece of their online strategy is structured and thought through, centring on maintaining a prominent presence on open social media platforms.

Most extremist narratives proliferate within closed groups on Facebook and Telegram. Some radical groups use specific websites archive.org and ok.ru to upload sermons by radical imams, teachings and statements, often translated into local languages. In recent years, online games have also been used to engage users and foster interest in the goals of radical groups with a view to their future recruitment.

The Role of Virtual Communities

Radical groups in North Macedonia are using the internet to promote involvement through the creation of virtual communities. Our analysis of Facebook pages and YouTube channels in both Albanian and Macedonian languages used by ethno-nationalists, radical Islamists and far-right extremists, reveals a deliberate strategy to radicalise social media influencers. The structure of these pages, their content, and the tone of their posts create a sense of online belonging based on rational and logical argumentation, reinforcing their common goals to expand their networks and mobilise their supporters.

These groups promote discourses that seek to dehumanise their perceived enemies (e.g., the West for the radical Islamist groups; Albanians, Greeks and Bulgarians for the ethno-nationalist Macedonian groups; ethnic Macedonians and Serbs for the Albanian ethno-nationalist groups; and immigrants or LGBTQ+ people for the far-right extremist groups). Membership is associated with various benefits, including a sense of belonging, special status or power. Members share common values, facilitating the expansion of their network by including new followers, members and sympathisers.

Virtual communities also serve as spaces to enhance interaction among supporters within their local communities. The use of chat rooms, mailing lists, and fora to facilitate communication between people who live close to one another allows radical groups to form both online and offline networks and bonds. This provides an effective means of publicising their ‘cause’.

Targeted Populations

Extremist groups in North Macedonia follow a common and predictable pattern in their online targeting. Radical Islamists mainly target the Albanian Muslim population but also adopt a pan-Balkan agenda. They focus on identifying vulnerable young Muslims who have experienced ethnic conflict, economic inequality, disillusionment with local politics, or frustration with Western integration. These populations are prime targets for radical Islamist propaganda claiming to protect Muslims from discrimination and injustice in the West.

The Albanian population is not the radical Islamists’ only target in North Macedonia; there are also pages and groups in the Macedonian language that advocate the superiority of Islam aimed at convincing ethnic Macedonians to follow their ideology.

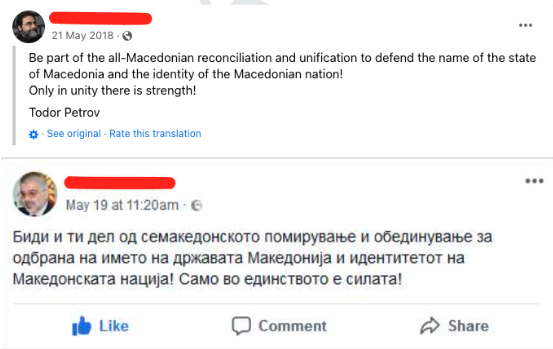

Fig. 1: Post on a nationalist Facebook group quoting far-right nationalist politician, Todor Petrov

Ethnic Macedonian nationalist groups advocate for the reconciliation and unification of all ethnic Macedonians (Fig. 1), regardless of their political affiliation, ideology, religion or other attributes, in order to protect national interests. They place emphasis on language and Orthodox faith as defining national characteristics. Their Facebook pages call for “Macedonians to stand up for themselves” against the global conspiracy and attempts to falsify their history and to stay “true to the cause, fight and die for the homeland”. Some groups go beyond ethno-nationalism; they promote anti-immigrant and anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, show support for far-right politicians like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán or and Slovenia’s Janez Janša, and condemn progressive values. In this context, ethno-nationalist extremism overlaps with political extremism.

The Albanian ethnο-nationalist groups target all the Albanian populations in the Western Balkans. Their content advocates for the unification of all Albanian-inhabited areas in the Western Balkans to redress the injustice allegedly done to the Albanian nation by the Western powers, which left the Albanian population scattered through the Balkans.

Community Reactions to Radicalising Content

Most of the analysed groups and pages serve as echo chambers for extremist content. Often, the comments go beyond reflecting agreement, instead amplifying and escalating even more extreme rhetoric. There are few attempts to express disagreement or debate, and when there is it is over specific details rather than the overriding message.

Members of ethno-nationalist, right-wing and Islamic radical groups react positively to content through likes, emojis, positive comments, and shares. However, the level of acceptance depends on the content and style of the posts. For example, posts that are less overtly extremist propaganda, such as videos of sermons by famous imams or ostensibly ‘patriotic’ statements, tend to be most popular and persuasive. Rejection or rebuttal, when it occurs, is based on logical arguments rather than personal insults to the author. This approach may potentially foster empathy and understanding, compared with the heated debates and threats that occur when commentators insult each other.

Posts by ethnic Albanian nationalists expressing the idea of Albanian unification are the most popular among online users. This material is widely followed by the Albanian diaspora in North Macedonia, Kosovo and South Serbia. The posts conveying political messages, including accusations levelled against the Albanian political parties for doing nothing to protect the rights of Albanians in North Macedonia are very popular, and trigger discussion with nationalist undertones. Among ethnic Macedonian nationalists, the most popular posts are those featuring anti-Albanian, anti-Greek, and anti-Bulgarian rhetoric. The commentators in these posts employ extreme language and hate speech and view opposition to these countries as a sign of genuine patriotism.

Online De-radicalisation

While many acknowledge the key role of cyberspace and social media in fostering counter-narratives aimed at deconstructing extremist narratives, this area remains unexploited by both governmental authorities and community-based NGOs. Community actors, including the police, lack the capacity to effectively engage with the online space, especially with chat rooms, gaming platforms and other open and dark spaces online. Local authorities often don’t have the subject matter expertise on how radical groups use the online gaming ecosystem to recruit supporters. It seems that extremists have introduced technological innovations faster than the official state authorities can respond to them, increasing their strategic advantage.

Some online spaces promote de-radicalisation. There are ethnic Macedonian and ethnic Albanian personalities advocating for peaceful coexistence in offline and online campaigns, and imams who publicly support the view that violence has no place in Islam. The North Macedonian P/CVE practitioners, who promote counter-narratives online, adopt a peer-to-peer approach, using personal messaging apps like WhatsApp to steer vulnerable people away from extremism.

However, these efforts are outnumbered by pages promoting radicalising content. The content that promotes positive messages garners lower reaction rates than posts, articles or commentaries that actively foster extremism. Not only is there less engagement with these posts, but commentators describe being less convinced by their messaging. One explanation to account for this is that the de-radicalising content is mainly formulated and circulated by state actors who are considered to be unreliable in the eyes of the local population. Despite this, our research indicates that counter-narrative content is still effective at increasing online users’ resilience to extremist propaganda. The low rates of engagement with these posts could be a result of users seeking to protect their identities.

Conclusion

This Insight argues that radicalisation prevention in North Macedonia requires authorities to harness the potential of cyberspace. The National Committee for Countering Violent Extremism and Countering Terrorism should develop an effective counter-messaging strategy, training local actors in how to produce persuasive counter-narratives. A cross-departmental entity should coordinate government efforts to counter violent extremist discourse. Moreover, effective media literacy and digital citizenship programs to enhance users’ resilience to radicalisation are essential. More structured and systematic research based on online content analysis in consultation with tech companies is necessary to understand the online extremist ecosystem in North Macedonia.

For a detailed report on the research done in North Macedonia see “Working Paper 5: Online and Offline (De)radicalisation in the Balkans” and “ELIAMEP Policy Paper 141: Understanding the Relationship Between Radicalisation and the Media in North Macedonia” produced in the context of Horizon 2020 PAVE Project.

Bledar Feta is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki, Greece and a Research Fellow on the South-East Europe Programme of the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), a think tank based in Athens. He is a member of ELIAMEP’s Horizon 2020 PAVE and GEMS projects’ research teams. He also provides consultancy services as a subject-matter expert in the field of radicalisation for different organisations, global analysis and advisory firms, and private companies, such as the Moonshot and the Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN). Twitter: @see-eliamep

Ioannis Armakolas, Ph.D. (Cantab.) is an Associate Professor of the Comparative Politics of Southeast Europe in the Department of Balkan, Slavic and Oriental Studies at the University of Macedonia, and Senior Research Fellow and Head of the South-East Europe Programme at the Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). He is the lead researcher in ELIAMEP’s Horizon PAVE and GEMS projects where he supervises research teams working on identifying and analysing key factors and trends in vulnerability to and resilience against violent extremism in the Balkans. Ioannis Armakolas has extensive experience as a consultant with USAID, DFID, RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network) and OSF projects in the Western Balkans. Twitter: @see_eliamep