In 2022, the humanitarian organisation World Vision published a report warning about the spread of anti-refugee messaging, in particular as it relates to Ukrainians. The report’s lead author, Charles Lawley, stated that although disinformation campaigns have been largely unsuccessful, they would fuel resentment towards fleeing minorities and the authorities assisting them if left unchecked. A year later, tensions surrounding the arrival of Ukrainians are rising in host countries, including in the United Kingdom, where “inflammatory rhetoric – and action – against asylum seekers … is reaching a tipping point”. Last year, there was a petrol bomb attack on an immigration centre in Dover. In February 2023, there were violent protests against hotels housing asylum seekers in Knowsley, including stone-throwing and setting a police van on fire. This violence has been pushed by the far-right, who believe that asylum seekers are stealing accommodation from homeless British veterans, for instance, and mapping the areas where Ukrainian refugees seem to be staying.

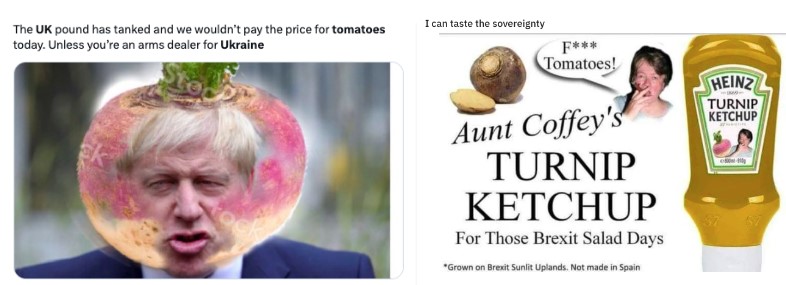

By analysing user commentary around post-Brexit memes on Twitter, Imgur, and Reddit, this Insight illustrates how these images are giving rise to violent speech targeting refugees and British democratic values. Memes have been shown to be crucial elements in the creation of digital hate communities. For example, memes used in alt-right circles have acted as harmful “units of cultural transmission” disguised as dark, politically incorrect jokes that attack progressive, democratic, and liberal thinking. The use of memes in online circles can thus be interpreted not just as an invitation to humorous fun, but also as a tool to draw users into ideologically-charged conversations, extremist or otherwise. In this case, post-Brexit meme culture seems to have become closely associated with the belief that UK and EU political elites are prioritising Ukrainian needs over those of Britain. This subject has been used as a means to spread harmful rhetoric against Ukraine, a phenomenon rooted in disinformation and collective anxiety that could feed aggressive nationalism and further increase the risk of violence against asylum seekers in Britain.

“So how is your Brexit going?”

Back in March 2022, then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson compared the Ukraine war to the Brexit vote. He said that Britons, just like Ukrainians, had the instinct “to choose freedom“. The comparison was harshly criticised by British and European politicians equally, describing Johnson’s words as “offensive” and “insulting” to Ukrainians, and a “national embarrassment”. In addition, the comment suggested that “the EU was itself a form of tyranny to be escaped from”. Johnson’s speech had the power to fuel and legitimise narratives that dismiss or even deny the tragic nature of Ukraine’s situation, while also demonising the European Union as anything but an ally. As a consequence, it enhanced Britain’s sense of victimisation and, in doing so, encouraged an unhealthy and populist form of nationalism – Britons first, and Britain above all.

Research has shown that in times of crisis, newcomers can be strategically attractive targets of hatred and oppression, becoming more likely to be exposed to violence. This violence can be encouraged by political leaders if they promote a sense of collective victimhood through populist rhetoric. Indeed, creeping inflation and recent shortages have watered the seed that Johnson’s populism planted in 2022. Only in the last month, dozens of memes have taken over the online sphere only to push for the idea that “UK [is] worse off than a warzone” or that Britain has “less stock than a country delved deep in an ongoing war”. And, to make the parallels between Britain and Ukraine sound even more legitimate, accusations that Russia was behind the Brexit-induced losses abound. In addition, claims that Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson were paid in fact by Russia, the KGB, and “banks” (Jews) to promote the Leave Vote are shared in ways that dissociate the British people from their actions, depicting Britons as victims not only of Russia but also of the elites who misled them for their own gains.

Anti-Russian discourse quickly becomes a violent rhetorical tool against the political establishment, with narratives encouraging the deaths of political leaders circulating online. Comments such as “God I f**king hope he gets done”, or “Get Nigel Done”, and “I’d pay good money to see that. What a c*nt” promote the idea that governments are corrupt and that only violence can bring the change that voting cannot, echoing the notion of accelerationism. Accelerationist justifications for violence have “suffused online white nationalist spaces” because the concept of accelerating the destruction of the (democratic and liberal) system is also closely related to the idea of a race war – necessary to avoid the ‘Great Replacement’ or ‘white genocide’. The idea is that in order to stop foreign invasion and subsequent replacement, established authorities need to be destroyed. Within this framework, conspiracy theories abound. Precisely, the post-Brexit meme culture has been infiltrated by the racist and anti-establishment QAnon conspiracy theory, which stems from antisemitic tropes about high-profile cabals and blood-drinking paedophiles represented by the liberal political elites, who need to be overthrown.

The post-Brexit meme culture blames Brexit losses on “a handful of inbred pedophiles”, and states that gains from the Leave Vote only benefitted “peadoes” [sic]. Lingering anti-vax sentiments also seem to influence fury against the state, with comments on Reddit such as “We’ve had enough of experts!” or “The whole system is gaslighting us!”, suggesting that the state has manipulated and controlled the British people to their benefit, and are choosing to “hand Ukraine billions” while “people [are] struggling in [the] UK”. The final proof that the elites at home and abroad are favouring Ukraine over Britain, even though the former has it “just a bit worse”, are… the tomatoes.

“The Great British Tomato Famine”

In February 2023, British Environment Secretary Thérèse Coffey urged Britons to “cherish” turnips amid food shortages. Shortages in Britain have been compounded by “high energy prices impacting UK growers, as well as issues with supply chains.” This has occurred as households struggle with food inflation “at a 45-year high”. In Ukraine, the war and adverse weather conditions in the fall caused a food deficit, with some experts talking about a new wave of 30-40% of price increases. That includes the price of tomatoes, which has seen an unprecedented rise in Ukraine “due to lack of imports from Turkey”. No one seemed to argue with that, until in late February journalist John Sweeney posted a video on Twitter reporting on the abundance of tomatoes in “Kramatorsk [Ukraine], 25 miles from Bakhmut.” The video has so far received 1.7 million views.

After Sweeney shared the images in Kramatorsk, the post-Brexit online culture shifted its focus to two main themes: 1) the EU favouring Ukraine and supplying it with tomatoes; 2) British politicians prioritising the sending of weapons to Ukraine while letting Britons starve. Those engaging with such narratives, especially the latter, might argue that humour was used as a resort in tough and complex times. But, as seen before on GNET, humour is also a useful tool in allowing individuals to dissociate from the content they share. In other words, using irony or sarcasm to spread disinformation, in this case targeting Ukraine and EU-UK political elites, can spread hatred towards refugees and sow distrust in the establishment. Memes emerging around both these themes, and the conversations developed around these, illustrate this fact.

“Incredible but true”, a user said, “Politicians ration tomatoes and lettuce while shipping weapons to Ukraine.” Brits online are “wondering if Ukrainians care about the poverty we suffer in the UK”, suggesting that perhaps Ukraine could “send us some fresh fruit and veg”. The “irrefutable facts” seemed to be that because “Ukraine is nice to the EU … they got the tomatoes” while the “UK [has] done Brexit and we got no tomatoes. (Or Turnips).” Countries in the European Union have no “empty shelves like the UK”, which makes the shortages in Britain either a choice orchestrated by the EU or the result of British political opportunism during Brexit.

British political opportunism plays a role now as well as it did during the Leave Vote, so the narratives go, namely by donating weapons and resources to Ukraine while British people struggle: “Ukraine [has] Tomatoes, but the UK doesn’t? Did we donate those as well, or did we exchange them for Turnips?”. It is only fair, say many in the mainstream online space, that “Ukraine return [the] generosity and send tomatoes to [the] UK”. What Britain needs is “humanitarian aid from Ukraine to [the] UK”. A user proposes launching a “Tomatoes for Tanks” programme. The proposal seems to repeat across platforms: “How about we send Ukraine arms, and they send us tomatoes?” From these conversations, it is clear that a sense of victimhood emerges as a result of narratives of imperilment combined with conspiracy theories and narratives around inequality. This sense of victimhood is crucial to understanding the potential of these memes for radicalisation, as feelings of unjust mistreatment prepare the individual for the acceptance of violence against a perceived enemy. Extensively used in right-wing populist politics in particular, these manifestations of victimhood can cut across partisan, ideological, and sociodemographic lines, strengthening a sense of collectivity, the ‘nation’, at the expense of the ‘other’.

Recommendations

Memes can constitute ‘borderline’ content that is harmful, but not illegal or violative. Because of this, memes are able to spread (coded) hate speech while remaining in the mainstream, rather than having to migrate to less regulated platforms. This means that deplatforming or banning content embedded in memes is especially difficult. While the takedown of borderline content should not necessarily be systematic, its impact could still be reduced through de-amplification. This involves reducing the impact of borderline content based on its potential to facilitate radicalisation and inspire violence, while protecting human rights and upholding the rule of law. If conducting de-amplification as a strategy against borderline content with potential for radicalisation, it is important that tech companies are fully transparent about their processes, so that users have the option to appeal and to mitigate the risk of unjustified or biased tech overreach.

The context of (dis)information is crucial, and so more focus on context rather than content is needed. A way to address this would be to identify clusters of data that work as radicalising tools only when displayed in combination. For example, the images of a tomato, a turnip and Boris Johnson are data points that separately would go unnoticed by most flagging systems. Now, these data points in the same picture could be related to, and ignite, a conversation against the British government in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Similarly, criticising paedophiles in the online sphere is rarely a reason to report a user. However, using the keyword ‘paedophile’ in a context where political elites are accused of being corrupt, is enough reason to report content, as it is likely connected to QAnon.

Collecting interdependent clusters of data as a way to nuance flagging systems would also assist with the identification of ideologically-intersected threats that do not neatly fit traditional categories or political binaries. In addition, this would assist with tailored interventions, diminishing the risks of regulatory figures being accused of being a source of grievance and so a target of violent extremist groups. Finally, since the same memes tend to reappear across (mainstream) platforms, it would be useful to incorporate clustered evidence in information exchanges about online threats and to add them to existing databases of harmful content.

Conclusion

This Insight illustrated how food shortages and rampant inflation in the UK have contributed to the increased presence of online disinformation and far-right content hostile to political elites on the one hand and vulnerable Ukrainian refugees on the other. Through the spread of memes, populist rhetoric and conspiracy theories intersect, resulting in the formation of an ‘us’ and ‘them’ worldview threatening established institutions and uprooted Ukrainian communities alike. As social inequalities deepen and, in turn, institutional responsibilities in the overall management of society become more critical, scepticism towards elites is likely to keep growing. As we learned during the pandemic, this scepticism can effectively be capitalised on by extremist individuals and groups to push for their own anti-democratic agenda into the mainstream with the aim to turn dissent into action.

In this context, post-Brexit memes as seen above can also constitute a threat to refugees, especially because current anxieties build upon nationalistic rhetoric that has been encouraged by populist political leaders since the Brexit vote. It is crucial to tackle not only disinformation, but to redress Britons’ sense of victimhood by nurturing a sense of agency at the individual level, and stressing the need for transnational cooperation at the national level. Allowing individuals to believe that Brexit was wrong but that putting Britain first is the way out promotes damaging (and incoherent) political thinking, and fuels the potential for alternative non-democratic action – even violence. Surely, that’s no one’s Brexit.