On September 14, 2022, the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs questioned current and former executives from four of the biggest social media companies—Meta, Twitter, TikTok and YouTube—on online extremism and menacing content on their platforms. However, as became evident during the hearing, the representatives largely deflected the politicians’ questions on moderation and safety efforts. The discussion lacked a more nuanced understanding of the social media exploitation by right-wing terrorists, which is discouraging given the deep relationship between the leakage of recent mass shooters’ manifestos and livestreams on these types of online platforms.

The same day, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill into law that “will require social media companies to publicly post their policies regarding hate speech, disinformation, harassment and extremism on their platforms, and report data on their enforcement of the policies.” The lack of transparency surrounding tech companies’ business models, such as the role of algorithms in online radicalisation, continues to pose a threat to (inter)national security.

This Insight is based on the study “The Contagion and Copycat Effect in Transnational Far-right Terrorism: An Analysis of Language Evidence”, which was authored by Julia Kupper, Tanya Karoli Christensen, Dakota Wing, Marlon Hurt, Matthew Schumacher and Reid Meloy. It examined the interconnectivity of manifestos, attack announcements on online platforms, livestreams and writings on equipment used during ten contemporary terrorist attacks that were committed by extreme right lone actors. The findings of this evidence-based research were recently featured in Perspectives on Terrorism, and are highlighted in this article.

Fact Patterns, Motivating Forces and Tactical Implications of Attackers

Between 2011 and 2022, ten lone-actor terrorists motivated by race and/or ethnicity attempted or carried out multi-casualty incidents across North America, Europe and Oceania. The assailants self-radicalised in cyberspace and were influenced by an intricate far-right ecosystem of digital platforms and narratives, including the Great Replacement conspiracy theory and accelerationist beliefs. This was reflected in the operational approaches of their offences when they converted their virtual frustration into violent, real-world action:

- Anders Breivik attacked a government building in Oslo and a labour party youth camp in Utøya, Norway in July 2011 to target liberal officials and their families. He emailed his manifesto to thousands of extreme-right individuals and groups in the hours prior to his violent acts and intended to livestream the beheading of Norway’s former labour prime minister on YouTube.

- Dylann Roof attacked a Baptist church in Charleston, SC, United States in June 2015 to target the Black community. He published his manifesto on his website the “Last Rhodesian” before his attack.

- Robert Bowers attacked a synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA, United States in October 2018 to target the Jewish community. He leaked an announcement of his attack on Gab, a far-right Twitter clone.

- Brenton Tarrant attacked two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019 to target the Muslim community. He disseminated his manifesto and a link to his Facebook livestream on the imageboard 8chan before the attack.

- John Earnest attacked a synagogue in Poway, CA, USA in April 2019 to target the Jewish community. He also distributed his manifesto and a link to his attempted Facebook livestream on 8chan shortly prior to his attack.

- Patrick Crusius attacked a supermarket in El Paso, TX, United States in August 2019 to target the Hispanic community. He uploaded his manifesto on 8chan prior to his act of hate-fueled violence.

- Philip Manshaus attacked a mosque in Bærum, Norway in August 2019 to target the Muslim community. He did not author a manifesto but shared a link to his attempted Facebook livestream on the imageboard Endchan before his attack.

- Stephan Balliet attempted to attack a synagogue in Halle, Germany in October 2019 to target the Jewish community. He uploaded his manifesto to the imageboard Meguca and broadcast his livestream on Twitch, an online streaming platform.

- Hugo Jackson attacked a school in Eslöv, Sweden in August 2021 to target the non-white community. He distributed his manifesto to friends on Discord, an instant messaging platform, and livestreamed his attack on Twitch.

- Payton Gendron attacked a supermarket in Buffalo, NY, United States in May 2022 to target the Black community. He uploaded his manifesto on Google Docs two days prior to the attack and shared it, along with his journal logs and a link to his Twitch livestream, on Discord.

The Interconnectivity of Recent Extreme Right Terrorism Attacks

On the surface, these acts of violence appear to be unrelated; however, the language evidence the perpetrators compiled prior to or during their offences reveals contextual patterns across their pathways of intended violence and emphasises the interrelatedness of these events. During the radicalisation process, the subjects studied manifestos and livestreams from notorious self-starter role models, which encouraged them to commit their own acts of violence. Throughout the planning and preparation stages, the terroristic communications were used as a do-it-yourself guide for tactical advice. In the course of the mobilisation phase, the perpetrators compiled their own manifestos while announcing their plans on digital platforms and livestreaming the event during the implementation. Subsequently, these elements create a propaganda tool for sympathisers and an operational manual for future imitators, which is part of the perpetrators’ strategy to target their intended audience.

To examine a possible contagion or copycat effect, we assessed a variety of written and spoken components through a forensic linguistic lens. This included eight manifestos, seven attack announcements on online platforms, four livestreams and three writings on equipment used during the incidents. According to co-author Dr. Reid Meloy, the concepts of contagion and copycat should be separated: ‘contagion’ refers to an imitation of the act after a widely publicised mass attack, typically several weeks. ‘Copycat’ describes the imitation of the act and actor and can extend over months or years.

Textual Samples of Content Patterns

Manifestos

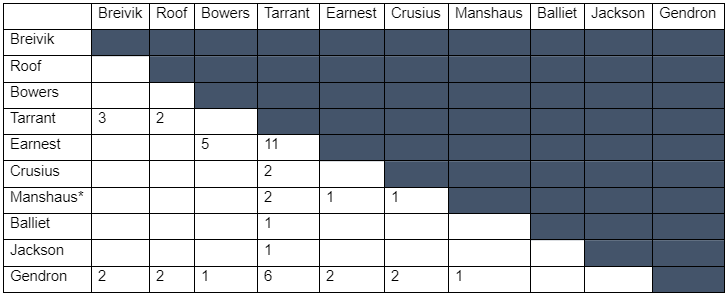

Multiple manifesto authors in our sample referenced the names of infamous predecessors that committed similar terrorist attacks in their writings. For instance, Brenton Tarrant alluded to Dylann Roof twice and Anders Breivik three times in his screed. John Earnest made remarks about Tarrant and Robert Bowers eleven and five times respectively in his manifesto, urging readers to “FIGHT BACK, REMEMBER ROBERT BOWERS, REMEMBER BRENTON TARRANT.” Patrick Crusius mentioned Tarrant’s name twice in his document, noting that “In general, I support the Christchurch shooter [Tarrant] and his manifesto.” Stephan Balliet alluded to Tarrant once in an unpublished document, claiming that “Is there anyone you want to thank? Yes, Brenton Tarrant.” Hugo Jackson made one reference to Tarrant in his writings and included a direct quote from him: “‘For the thousands of European lives’ – Brenton tarrant [sic].” Payton Gendron referred to Tarrant six times, with Breivik, Roof, Earnest and Crusius mentioned twice, and Bowers and Manshaus once.

Table 1: Number of mentions of previous perpetrators’ names across manifestos

[*Manshaus did not author a manifesto but referenced infamous predecessors in his online announcement of the attack]

Gendron’s pamphlet also included copying extensive amounts of structural components from Roof, Tarrant and Balliet, as well as plagiarising textual elements from previous communications. As such, he duplicated entire pages from Tarrant, only occasionally revising certain phrases to adjust the content to his mission. The examples below are from their self-interview sections, a meme format that has been repeatedly utilised in recent far-right manifestos:

- Tarrant: “Did/do you personally hate muslims? A muslim man or woman living in their homelands?” and “By living in New Zealand, weren’t you an immigrant yourself?”

- Gendron: “Did, or do you personally hate blacks? A black man or woman living in their homelands?” and “By living in the United States, weren’t you an immigrant yourself?”

Attack Announcements on Online Platforms

Within minutes prior to their acts of violence, numerous offenders in our study leaked short messages to announce their intended attacks on imageboards, such as 8chan. Several forms of thematic overlap were noted within these communications; for example, three perpetrators directly encouraged readers to commit similar attacks:

- Crusius: “Keep up the good fight.”

- Manshaus: “i was elected by saint tarrant after all (…) if you’re reading this you have been elected by me”

- Jackson: “You! Are the chosen one. and one that will maybe see this life. (…) I’m rootin for ya lads”

The theme of ‘selecting’ a subsequent imitator could have originated in Tarrant’s manifesto, who claimed that: “But I have only had brief contact with Knight Justiciar Breivik, receiving a blessing for my mission after contacting his brother knights.”

Livestreams

Four lone actors in our sample successfully livestreamed their attacks with a GoPro camera attached to a helmet, mimicking the idea of a first-person shooter video game. One of them was Hugo Jackson, who had the following quote written on his bedroom wall: “Hi my name is Anon, and I think the holocaust never happened. Feminism is the cause of decline of the West which acts as a scapegoat for mass immigration and the root of all these problems is the Jew.” This is a direct reference to Stephan Balliet’s opening statement during his live broadcast of an attempted mass shooting at a synagogue two years prior to Jackson’s attack.

Furthermore, three perpetrators wrote the names of previous extreme right terrorists on their equipment utilised during the incidents: Brenton Tarrant pencilled the names of attackers from Europe and North America on his firearms and magazines, including Pavlo Lapshyn, Anton Lundin Pettersson, Alexandre Bissonnette, Darren Osborne and Luca Traini. Hugo Jackson scribbled Stephan Balliet and Anton Lundin Pettersson on the mask that he wore during the event, while Payton Gendron wrote the names of Anders Breivik, Dylann Roof, Brenton Tarrant, John Earnest and Philip Manshaus on his weapons.

Conclusion

It is possible that we have entered the fifth wave of global terrorism. The interconnectivity of language evidence compiled by extreme right actors validates the theoretical argument that a resonant fifth wave has begun. Manifestos and livestreams appear to empower copycats and escort them through the stages of radicalisation, mobilisation and implementation, while the viral contagion is spread in a complex far-right online ecosystem. To identify and mitigate these threats, we need to take a collaborative approach: funding innovative programs and developing algorithms that can detect these digital signals, which can then be analysed by interdisciplinary threat assessment teams on the ground. Governments need to fund such work and legislate reforms that will compel the oversight of tech companies, who need to be liable for the content they host.