Over the past several years, there has been increasing attention paid to the use and exploitation of digital platforms by networks of homegrown violent extremists, terrorists, and other non-state actors. While the electronic bulletin boards and listservs of the 1990s were replaced by more interactive platforms (i.e., Web 2.0), the need to secure, conceal, and anonymise operational planning grew in importance. This brief exploration will examine how these practices are being developed and promoted by clandestine networks of violent actors, focusing on the far-right.

Despite not representing a new approach to knowledge transmission, in the last few years, digital platforms including Telegram, Discord, Gab, and VK have become lightning rods for the far-right. In their short lifecycles, these far-right digital communities have moved towards greater professionalisation through the production and distribution of OPSEC training advice and materials. As of May 2020, there are at least four Telegram channels focused primarily on promoting digital and physical security practices from a far-right, neo-Nazi, and/or fascist accelerationist perspective. These are briefly listed below without identifying information to avoid amplifying their readership:

- Channel #1: ~3,500 subscribers, and describes itself as “Everything privacy, security, and opsec related. VICE review: ‘…one well known neo-Nazi channel that provides tradecraft to evade authorities online.’”

- Channel #2: ~2,700 subscribers, and describes itself as “Ham Radio lit for fashy shit.”

- Channel #3: ~600 subscribers and no channel description

- Channel #4: ~120 subscribers, and describes itself as “Intel organization by volunteers to destroy the enemies of the white race”

All of these channels, to varying degrees, circulate a mixture of practical, security-themed advice, and anti-Semitic, racist, and related far-right memes, articles, and commentary. All of these channels are available to anyone, without verification (i.e., public), if the user possesses the correct address.

Some of these entities function largely to replicate and redistribute information and guidance from established sources, yet some have emerged as content producers, such as “OPSECGOY,” who began distributing their guide, Privacy Checklist: A privacy & security goys™ checklist, in March 2020.

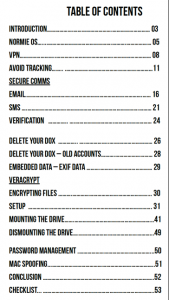

This 54-page guide features discussions of:

- “normie tier operating systems” (i.e., Windows, Mac OS as opposed to Unix/Linux variants),

- text message, email, file, and full disk encryption,

- using Virtual Private Networks (VPN) and securing internet browsers (e.g., understanding browser fingerprinting),

- using the Onion Router (Tor) network, various browser add-ons, and privacy-conscious search engines (e.g., they suggest SearX),

- removing one’s listing from data brokers,

- removing metadata embedded in media files (e.g., EXIF),

- managing passwords securely,

- faking device identifiers such as MAC addresses (i.e., spoofing), and

- generating disposable telephone numbers to register for online services.

The guide ends by thanking the reader and encouraging follow up using email encryption (e.g., PGP or web-based services such as ProtonMail), accessing materials via a ‘dark web’ onion address, or via Telegram. There is also a cryptocurrency address, managed by Monero, for those seeking to send financial contributions.

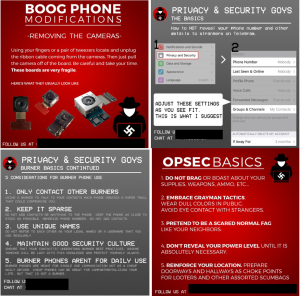

The OPSECGOY network has also produced and circulated dozens of infographics designed to demonstrate a variety of skills as shown below:

The stylised square blocks are carefully branded with the groups’ logo and include contact details. Amongst the graphics located, they detail a variety of skills including:

- Basic behavioral OPSEC (e.g., avoid bragging, blend in, harden location)

- Modifying cell phones (e.g., removing cameras, microphones, and batteries)

- Acquiring and using disposable cellphones (i.e., burners)

- Advanced digital security practices (e.g., verifying encrypted file signature, encrypting DNS, securing Telegram, password generators)

- Maintaining online anonymity through VPNs, Tor

The infographics and OPSEC guide were circulated on a series of far-right Telegram channels and continue to be produced on a regular basis. As platforms such as Telegram respond to far-right networks utilising their services, channels are occasionally banned, and users removed. In response, activists have created aggregator bots which gather ‘banned’ channel content and rebroadcast it on not-yet-banned channels, effectively circumventing any censorship. When Apple moved to prevent some far-right channels from displaying on iOS devices, activists shared numerous detailed workarounds to allow continued access to banned material.

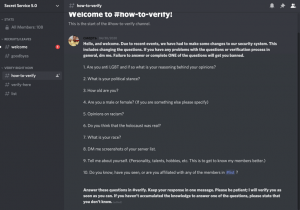

Other platforms such as Discord, which has been shown numerous times to house neo-Nazi and other far-right groups, provide further evidence of a focused, adaptive concern with promoting security, and resisting external infiltration. In a review of several dozen far-right Discord chat servers and Telegram channels, I observed increasingly-rigorous innovations attempting to vet and screen potential new members. In a typical example, one chat server (now offline) whose avatar was a hooded Ku Klux Klan member seated in front of a noose, required potential participants to answer a series of questions to establish their political views and identity, and to provide a screenshot of the other chat servers the user is subscribed to.

The chat server’s owner presents these questions, writing: “due to recent events, we have had to make some changes to our security system.” This speaks to the need for groups to engage in near-constant innovation to avoid identification, disruption, and infiltration by opponents.

Other groups amongst the far-right have shown similar desires to advance their security posture, such as the April 2020 announcement by the National Socialist Agency (NSA) that “the time has come for us to take things up a notch,” and to establish their own “intelligence agency.” The NSA states that its objectives are “identifying and prioritizing enemies, infiltration, sabotage, [and] disinformation,” and noted that participation with the group was restricted to “opsec legend[s].”

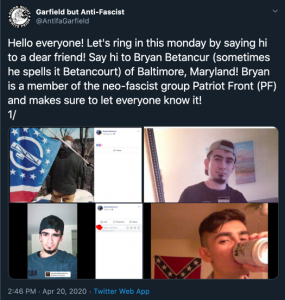

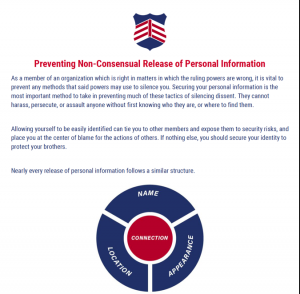

Other far-right groups have produced guides similar to OPSECGOY’s, some of which are designed exclusively for intra-group distribution, and thus circulated only on ‘vetted’ platforms, such as invite-only spaces hosted using Rocket Chat, Discord, Gab, and Telegram. One such ‘not for publication’ guide published by Patriot Front, and (ironically) tilted Preventing Non-Consensual Release of Personal Information, is distributed to the group’s approved members to help limit their exposure. This six-page guide was produced in response to the many Patriot Front members who have been exposed (i.e., doxed) by anti-fascist, and other researchers and thus represents a reactive approach to data leakage and poor OPSEC.

The Patriot Front guide is focused on members maintaining separation between their real name, physical location, appearance in photographs, and their activity with Patriot Front. As the author(s) remark:

Your real name should be withheld in all cases, your specific location of residence should be restricted, and your appearance should be guarded, all in line to keep your enemies from establishing a final connection with the organization. It is vital to compartmentalise these aspects of information from each other, as well as making as many of them as completely inaccessible as possible.

The guide encourages members to compartmentalise and silo their lives—separating one’s “identity in activism” (i.e., fascist activities) from one’s “real online identity.” The publication offers a scattered assortment of guidance for selecting usernames, avoiding linkages with one’s phone number, and maintaining anonymity in digital and “IRL” (in real life) settings.

The Patriot Front guide briefly details standard OPSEC practices such as concealing identifying information in photographs (e.g., tattoos, logos), safety and masking at public events, and how to meet potential new group members. For this last task, key to grow the network, the author(s) advice includes:

- Meet in public

- Arrive early and scout the area

- Park a distance away, out of view

- Know what the person you are meeting will be wearing so you can “see him before he sees you”

- Mitigating possible surveillance, watch for cameras and recording devices

- Ask about their personal political history and aspirations

- Do some “light activism” (e.g., posting stickers)

The Patriot Front guide ends by listing online practices (e.g., Tor, VPN, disabling Bluetooth/WiFi, avoiding Google, not leaking metadata) as well as various data brokers that activists can contact to have their data removed. The guide has gone through several versions, with earlier, shorter versions leaked and distributed by anti-fascist activists.

As these movements continue to operate, we can expect further innovation and hardening of these practices, as well as a further push towards what the FBI terms ‘going dark.’ The dual use of technological innovations by violent non-state actors is not a new challenge, though the consumer-level promotion and adoption signals a more serious focus by movement strategists and technical experts. Following more active periods of disruption and repression by law enforcement, we can expect these efforts to increase. Such a surge of interest in OPSEC could be seen after a series of arrests targeting members of neo-Nazi accelerationist networks Atomwaffen Division, Feuerkrieg Division, and The Base in early 2020. Following these arrests, Telegram’s far-right channels were abuzz with talks of securing communications, detecting infiltration, and avoiding detection. Numerous accelerationist factions announced their dissolution in the immediate aftermath of the arrests. As efforts to identify, disrupt, and make arrests amongst these networks continue, the resulting arms race of innovation is likely to continue in lockstep, as activists try to stay one step ahead of law enforcement and intelligence officials in a never-ending race towards opacity, anonymity, and operational security.