This Insight examines the return of 325, an insurrectionary anarchist zine, and the renewed prominence of anti-technology positions in its 13th issue, titled “Back to Basics.” This 76-page-long document, originally released in March 2025 with the PDF online version circulating later in September, articulates a worldview that regards advanced technologies not as neutral tools but as a totalising system of domination, a “mega-machine” that both enslaves and alienates. This framing has increasingly tangible consequences as similar narratives appear in communiqués claiming attacks on technology-related infrastructure and supply chains. The current trajectory of insurrectionary anarchist anti-tech discourse and practice reflects a deeper unease with the accelerating pace of technological change that intersects with pre-existing anarchist, primitivist, and eco-extremist traditions.

325’s Revival

325 has long served as a hub for the dissemination of insurrectionary anarchist theory, analysis, and propaganda. Founded in 2003, it developed into a “clearing house of general news, reports, communiques, publications, event listings, etc.” from informal anarchist affinity groups. While it initially covered issues ranging from anti-capitalism and anti-civilisational perspectives to support for prisoners and other causes dear to anarchists, the most recent issues – in particular, issues #10, #11, and #12 – shifted the focus to anti-technological topics. Despite the appearance of non-violent discourse, the zine frequently features insurrectionary texts, including claims of responsibility for actors’ violent acts and sabotages. This practice of sharing information and knowledge is intimately linked to the principle of “reproducibility”, that is, the idea that one’s actions can inspire other people, thereby propagating the conflict.

The seizure of its hosting server, nostate.net, by the Dutch police in November 2020 seemed to have sealed its fate. Yet in 2025, 325 resurfaced on various anarchist-affiliated websites and blogs with its 13th issue (henceforth #13), titled “Back to Basics.” #13 opens by stating its intention to continue “the anti-tech analysis that we have been developing” in the previous issues. In doing so, it reflects a deep continuity with earlier anarchist critiques of technological civilisation, while also combining it with updated targets and grievances. The exact reason why 325 resurfaced this year remains unclear. Although anarchist anti-tech positions have continued to circulate on other platforms in the last few years, the revival of the zine can be interpreted as further evidence of the growing entrenchment of these ideological beliefs within the anarchist milieu.

The Machine-led Totalitarianism of the Prison-Society

Issue #13 presents a vision of technology as inherently destructive and totalising. Artificial Intelligence stands as the most visible expression of this trend: a form of power that, rather than liberating humanity, binds it ever more tightly into systems of surveillance and exploitation. Technology, in this framework, is not merely a collection of tools but a living, expanding system that imposes its own logic upon society, posing a material, ontological, and existential threat simultaneously.

This position draws from a long-standing current within insurrectionary anarchism, at the heart of which lies the notion that technology forms an autonomous and enslaving system. According to this perspective, no government, corporation, or class truly controls technology. Rather, technology itself dictates the terms of human existence. The outcome of this is a “prison-society,” a totalitarian system of pervasive surveillance and control in which freedom becomes impossible. As one contributor to #13 puts it, “the new humans being raised in the nurseries of the new order are sung lullabies of the technocratic propaganda machine,” effectively preventing resistance by annihilating any capacity for critical thinking.

The insurrectionary anarchist critique of technology also identifies a human component in this system of domination. These “techno-elites” – an amalgamation of socio-economic, political, and technological elites – are said to embody the interests of technology; yet, even as they benefit from the technological system, they remain ultimately subservient to it.

The arrival of the Technological Singularity – the predicted moment when AI surpasses human intelligence – represents the culmination of this purported totalitarian project. As technological civilisation is portrayed as irreformable, the only possible response to this is to pursue and accelerate its collapse.

Figure 1: An essay featured in issue #13 that focuses on the existential threat posed by AI.

This commitment resonates with a broader constellation of anti-technology actors, such as eco-extremists and eco-fascists. Although these milieus diverge ideologically, they converge on a shared conviction that technology represents an existential threat. Across these movements, technology is portrayed as an all-encompassing “mega-machine” that comprises physical infrastructure, an ideological force promoting perpetual progress, and the human component (“cogs in the machine”) that sustains it. Resistance is framed as both material and spiritual: a struggle that aims to ensure humanity’s survival, but also to protect the environment.

A pervasive sense of apocalyptic urgency underlies this worldview. The acceleration of technological change is interpreted as a sign of impending catastrophe, whether social, ecological, or existential. Given this worldview, violence against the machines – and the humans who maintain them – becomes both a moral imperative and a strategic necessity; a means to hasten the downfall of technological civilisation and reclaim our human agency and truer relationship with nature.

“Back to Basics”: The Core Arguments

Issue #13 echoes pre-existing anarchist tropes that depict technology as the defining structure of domination: the mega-machine. It describes technology as “a weapon, a doctrine, a god,” conflating it with civilisation itself. Contributors such as John Zerzan, an influential anarcho-primitivist, argue that the technological society constitutes a “global, totalizing civilization” that must expand to survive: “like cancer, civilization must grow or die.” In line with previous anarchist documents, three dimensions of domination emerge within the mega-machine.

The first is physical: the everyday technologies – “[f]rom smart CCTV (…) to border area and wilderness surveillance infrastructure based off-planet through satellites” – that constitute the material fabric of control. The second is ideological: the “dogma of growth and profit” that pumps lifeblood into the mega-machine, rationalising and justifying its relentless expansion. The third is human: individuals who have been “programmed, obedient, submissively producing, consuming, destroying, dying.” With this realisation comes a call to participate in one’s apparent own liberation. Alongside these so-called ‘enslaved individuals’ stands a small clique of techno-elites made up of “almost exclusively male coders and scientists, the futurists and transhumanists, the greedy politicians and entrepreneurs” – who, as one contributor writes, play “Russian roulette with our existence using algorithms for bullets.”

Environmental collapse and destruction are also central motifs of the issue. The zine argues that advanced technology, particularly AI, demands immense ecological sacrifice, consuming vast resources and causing irreversible damage. The relationship between technology and nature is framed as a struggle between the mechanical and “the wild, the organic, the untameable.” This narrative, long familiar within eco-extremist circles, casts technological progress as inherently anti-natural and, therefore, anti-human.

The threat, however, extends beyond the environment. Humanity itself faces extinction or transformation, according to 325. Issue #13 envisions a future where human beings either perish or evolve into a post-human hybrid, Homo Technologicus or Humanity+, absorbed into the machinery they once controlled. This apocalyptic horizon, centred on the approach of the Technological Singularity, provides both emotional intensity and moral justifications for violent resistance. The confrontation with the mega-machine cannot be delayed or moderated; instead, it must be accelerated, forcing the system toward collapse.

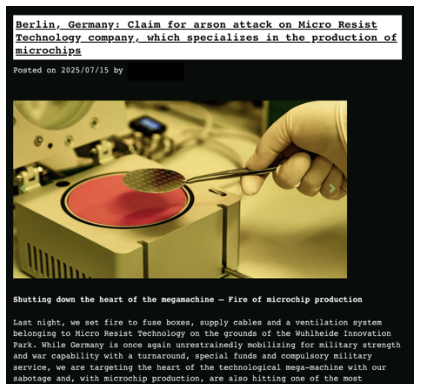

The practical expression of this accelerationist strategy is articulated through the “hit where it hurts” logic. Back to Basics urges militants to study the technological system in order to identify its weak points and disrupt its vital functions. For example, one essay identifies semiconductors – such as microchips – as a strategic weak point, citing Mustafa Suleyman’s “The Coming Wave” to argue that microchips constitute the “heart” of the technological order. This analysis mirrors real-world events: in June 2025, an anarchist cell called M.R.M.D (micro resist – mega damage) claimed responsibility for an arson attack on Micro Resist Technology in Berlin, explicitly describing the act as an attempt aiming at “stopping the heart of the mega-machine.”

Figure 2: An excerpt of the communiqué claiming responsibility for the attack against Micro Resist Technology in Berlin in June 2025 (communiqué posted in July 2025).

Although the zine does not explicitly reference him, this logic appears to draw heavily on the legacy of Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber, who, after all, published an essay titled “Hit Where it Hurts.” Previous issues of 325 had already positioned Kaczynski as a precursor of the contemporary anti-tech struggle, arguing that the anti-tech fight that anarchists are waging is part of the same struggle that the Unabomber launched in 1978. The new issue sustains that lineage while reaffirming the principles of leaderless resistance and informal organisation.

Consistent with tradition, #13 concludes with an extensive chronicle of claimed anarchist attacks worldwide, consolidating its function as both an ideological and operational node within the network.

Between New Elements and Persistent Tensions

Despite its strong continuity with earlier issues, Back to Basics introduces some notable innovations. Among these is the advocacy of 3D-printed firearms – a technology that is already popular among various extremist milieus. In the essay Revolutionising Power: 3D Printed Firearms for the People, the author argues that such weapons embody the anarchist ethic of self-reliance and decentralisation. By enabling individuals to manufacture weapons outside the control of states or corporations, 3D printing is framed as both a technical and symbolic act of liberation; an inversion of the technological hierarchy they seek to destroy.

Figure 3: A snippet of the essay advocating for the adoption of 3D printed firearms.

One might wonder how technology like 3D printing can be endorsed within a network that is fundamentally anti-technological. The answer to this question is twofold. First, the necessity to “fight fire with fire” justifies resorting to technology in order to destroy technological civilisation. Second, it is not uncommon to see anti-technology anarchists distinguish between “small-scale” (or tools) and “large-scale” (or organisation-dependent) technology. According to this distinction, which hails from the Unabomber, large-scale technologies rely on the division, organisation, and exploitation of labour as well as the extraction of resources to function. Contrastingly, small-scale technologies can be operated by individuals or small communities without relying on external assistance. From this perspective, 3D printed firearms would constitute small-scale technologies as they would allow anarchists to arm themselves without having to rely on any third party.

Another revealing aspect of Issue #13 is its subtle traces of conspiratorial thinking. Though less developed than in far-right milieus, this issue appears to allude to conspiracy theories in a few passages, without, however, providing a full-fledged discussion or explicitly mentioning any “well-established” theory. When talking about the techno-elites, phrases such as “they are already drinking the blood of their own children in order to evade death” bear a close resemblance to QAnon theories. Although the meaning behind it remains vague, this kind of phrasing exudes a conspiracy-leaning ideology, suggesting that fragments of broader conspiratorial narratives may be filtering into anarchist discourse.

Other topics discussed in #13 explore the gender dimension of the technological system, which is described as “patriarchal” – not least because of the role of the “almost exclusively male coders and scientists.” This observation also serves as a powerful reminder of an unresolved tension within the insurrectionary anarchist worldview. On one hand, humans are portrayed as powerless cogs within the mega-machine; on the other, certain humans – the techno-elites – are endowed with considerable agency and moral responsibility. This oscillation exposes an ambiguity: while it is said that domination resides in the system itself, the centrality of the techno-elites emerges time and again, owing to their role in building and sustaining the system.

In addition to discussing the above topics, Back to Basics situates the insurrectionary anarchist anti-tech struggle within contemporary debates on ‘green’ technology, data colonialism, and the changing nature of warfare due to advancements in military technology. It connects local struggles from Chile to Italy, presenting a global narrative of resistance to the technological order and, more broadly speaking, oppression. While its framing recycles familiar anarchist critiques of technology and civilisation, it also demonstrates an evolving nature adapting to new technological realities, as the discussion of semiconductors shows. This contributes to ensuring continued resonance within the insurrectionary anarchist milieu.

Policy Recommendations

The evolving landscape and characteristics of anti-technology extremism – both within and outside insurrectionary anarchism – warrant close scrutiny. Monitoring both the online discourse and the practical dimension of this phenomenon could lead to the establishment of a “shared threat library” of anti-technology violence, not unlike the Hash-Sharing Database developed by GIFCT. This initiative, which should connect academia, tech companies and stakeholders, and law enforcement, would highlight current trends and dynamics while also acting as an early-warning indicator system when new trends – like targeting semiconductors – emerge.

–

Mauro Lubrano is a Lecturer in International Relations in the Department of Politics, Languages, and International Studies at the University of Bath. His research focuses on anti-technology extremism, leaderless resistance, and innovation processes in violent non-state actors.

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.