For over a year, neo-Nazi networks have been exploiting readily available AI voice-cloning tools to produce English-language versions of Adolf Hitler’s speeches, circulating them on TikTok, X, Instagram, and YouTube. These AI-generated videos have collected over fifty million views according to a report published by ISD in September 2024, subtly normalising extremist ideology by recasting Hitler as a misunderstood leader and embedding antisemitic or conspiracist narratives into emotionally engaging content, while continuing to elude platform moderation. This Insight examines how these deepfakes are created, how they spread extremist messages without overt symbols, assesses the effectiveness of current platform responses, and offers evidence-based recommendations for stakeholders operating under the Digital Services Act.

The Genesis and Technical Architecture of AI-Generated Hitler Speeches

Since January 2024, extremist content creators have been making use of commercially available voice-cloning services, most notably ElevenLabs, to produce high-quality English versions of Hitler’s speeches, originally delivered in German. The process is easy; users simply need to take short audio clips from archival recordings, upload them to the cloning platform, and within minutes, they receive an English-language version that retains the original speaker’s rhythm and vocal tone. These clips, which usually do not exceed 30 seconds in length, are then combined with visual material and ad-hoc soundtracks, both carefully chosen. The music genres paired with Hitler’s speeches are usually popular ones, especially among the younger audience, who constitute the primary target of the neo-Nazi networks creating these AI-generated videos.

The visual strategy employed by loosely coordinated clusters of neo-Nazi content creators, including identifiable networks such as “NazTok” (documented by researchers at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue), operates with a clear intent to avoid automated content moderation across TikTok, Instagram, X, and YouTube. While all four platforms deploy automated moderation systems to manage the immense volumes of user-generated data, the sophistication and reliability of these systems remain uneven: TikTok and Instagram extensively use AI-driven image and symbol detection, while X and YouTube pair machine learning classifiers with large teams of human moderators who review flagged content. YouTube’s leadership on disclosure requirements for synthetic and altered content is particularly notable, and users are required to label manipulated content at upload.

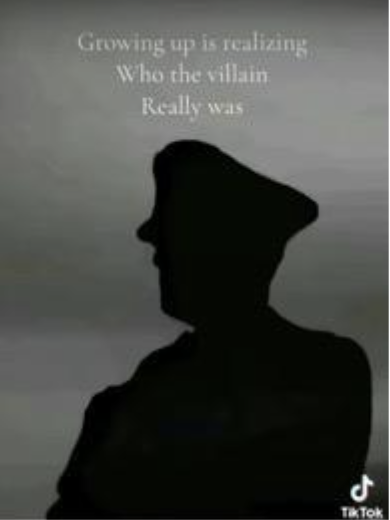

While these types of policies represent important progress, research suggests that enforcement and compliance sometimes fall short. This is because the creators of the AI-generated videos adopt a minimalist style that reduces the likelihood of triggering the filters used by platforms to identify and remove extremist and violent content. There is no direct incorporation of Nazi iconography, such as swastikas or SS runes; instead, creators include subtle chiaroscuro silhouettes of Hitler, often blended with soft backgrounds. One TikTok video exemplifying this technique featured a silhouette accompanied by the caption “Growing up is realising who the villain really was”, a sentence that is widely interpreted within extremist circles as a coded reference to antisemitic conspiracy theories. Moreover, this type of dog-whistling language makes enforcement exceptionally difficult. The video gathered 548,000 views before being removed by the platform, following external reporting. The video has since been reposted by multiple users, with the most recent upload dated 21 October 2025.

Figure 1. TikTok video example: Hitler silhouette with caption “Growing up is realising who the villain really was.”

The origins of these deepfakes can be traced back to January 2023, when ElevenLabs released a beta version of its voice-cloning platform. Within days, the company admitted it was facing “an increasing number of voice cloning misuse cases” after users on 4chan created audio clips using synthetic voices of public figures to read passages from Mein Kampf or spread racist messages. ElevenLabs later introduced safety measures, such as consent verification and account monitoring, but these have not been enough to stop extremists from abusing the technology. By October 2025, the company had partnered with the Japanese non-profit AILAS to develop stronger voice identification tools, yet extremist groups continue to exploit the platform to produce propaganda.

Viral Dissemination and Algorithmic Complicity

The spread of AI-generated Hitler speeches across social media is not only driven by a combination of emotional design – meaning the deliberate pairing of music, pacing, and aesthetic visuals to evoke strong reactions in the viewers – but also by the way platform algorithms work. Specifically, according to TikTok’s official For You feed Eligibility Standards, the platform’s recommendation system monitors user behaviour signals such as likes, shares, watch time, and comments, treating these as indicators of positive engagement and continuously refining suggestions to show users more similar content. TikTok explicitly states in its Community Guidelines that it does not allow hate speech, hateful behaviour, or promotion of hateful ideologies, and that such content – including material from violent extremists – is made ineligible for the For You feed. Nevertheless, users’ “For You” page – TikTok’s personalised feed designed to help discover a variety of content and creators – can still be filled with related images and videos when extremist content evades detection, creating reinforcement loops that draw individuals who began with only transient exposure into deeper engagement with such material. Research conducted by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue showed the extent of this trend in mid-2024. AI-generated Hitler content and posts glorifying Nazi ideology reached millions of views across most mainstream social media platforms. On X alone, a small number of posts attracted a considerable number of views in a matter of days. One video posted in February 2024, showing real war-time footage paired with AI-generated English audio from a 1935 Hitler speech, was viewed nearly eight million times and is still available as of October 2025. Similar videos on YouTube also gathered large numbers of views and demonstrated persistent accessibility.

Covert Incitement: Violence Without Explicit Exhortation

Although AI-generated Hitler speeches rarely contain explicit calls to violence, they act as powerful tools of ideological normalisation and emotional radicalisation. They work not through open incitement but by gradually reshaping perception and lowering moral resistance to extremist beliefs. This process tends to unfold through three main dynamics: historical revisionism, emotional manipulation, and social reinforcement.

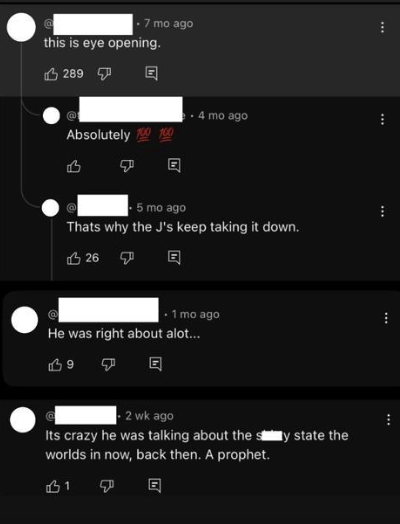

Many of these videos try to rewrite history by presenting Hitler as a misunderstood figure rather than a dictator responsible for genocide. By scrolling through the comments on X or YouTube, it’s very easy to find people insisting he was “right”, calling him a “Prophet”, or claiming the Allies invented lies to destroy his reputation. Some even suggest that his speeches were hidden from the public to “silence the truth”, or that they are removed because they are “eye opening”. Once this kind of revisionism takes hold, it chips away at historical reality and opens the door to extremist thinking.

Figure 2. Comments from users under AI-translated Hitler speeches on YouTube. The first comment and its subsequent replies appeared under a video uploaded one year ago, with the latest reply dating back four months. The second comment was posted in September 2025, under the same video. The third comment appeared in October 2025, beneath a newer AI-translated Hitler speech uploaded in July 2025. All comments remained publicly accessible until October 2025, when YouTube removed the videos and related threads following reports of Hate Speech policy violations.

The emotional packaging of these videos does the rest of the work, because the speeches are often paired with idealised or stylised visuals that purposely give a sense of belonging. That emotional appeal lowers viewers’ guard and makes them more receptive to the underlying ideology, even when they might not be fully aware of it.

Around this content, the comment sections become part of the radicalisation process itself, because they often function like an informal recruitment space where open praise of Hitler goes unchallenged and even gathers support. When users see others endorsing the same views, it creates the illusion of legitimacy and community. Extremist actors further exploit this by coordinating campaigns on platforms, where users are instructed to like, share, and repost content to boost its visibility and create a false image of organic popularity.

Platform Responses

All platforms examined for this Insight officially prohibit hate speech and the promotion of violent ideologies, yet enforcement against AI-translated Hitler speeches remains inconsistent. This inconsistency stems largely from the fact that much of this content falls into what researchers and tech policy experts term the “lawful but awful” or “borderline violative” category: material that is deeply troubling but does not explicitly violate platform rules as written. GIFCT’s 2023 analysis of borderline content – which remains the operative framework as of 2025 – identifies this challenge: content that “comes close to violating policies around terrorism and violent extremism” or “brushes up against a platform’s policies” without clearly crossing the line. Therefore, if no obvious Nazi symbolism or violent images are included, the filters may not flag the content as something that is violating the community guidelines. While GIFCT’s updated 2025 Incident Response Framework has strengthened cross-platform coordination for responding to clear terrorist events, the challenge of borderline content that normalises extremist ideology remains an area requiring continued policy development.

Enforcement action varies by platform.

- TikTok has taken a very strong stance against such content, removing many AI-translated Hitler videos and even redirecting searches for certain hate slogans to educational material. The platform’s 2025 enforcement report shows it removed 189 million videos globally for Community Guidelines violations, with 99.1% detected proactively and 94.4% removed within 24 hours.

- Instagram has implemented some warning labels, but little beyond that. Significantly, Meta – Instagram’s parent company – relaxed its hate speech moderation policies in January 2025, eliminating third-party fact-checkers and shifting to a user-reporting model that reduces proactive content removal. The EU subsequently charged Meta on 24 October 2025 with failing to provide adequate mechanisms for users to flag illegal content, under the Digital Services Act.

- YouTube’s hate speech policy explicitly prohibits hateful ideologies such as Nazism, and the company removes content once notified. The platform’s effectiveness remains reactive, with detection and removal following external reporting – an industry-wide challenge for all major platforms when confronting ‘borderline’ or symbol-light extremist media.

- X continues to host and recommend content that openly eulogises Hitler or echoes neo-Nazi propaganda, with algorithms quickly steering users toward more extreme content after just a few clicks. Research published in September 2025 by the Center for Countering Digital Hate and Jewish Council for Public Affairs found that X has become “one of the most effective tools for spreading antisemitism in history”, with hate speech remaining 50% higher than pre-Musk acquisition levels.

Another issue is that even when content is removed, it quickly resurfaces elsewhere. Videos taken down from TikTok reappear on Instagram, and clips deleted from YouTube are uploaded again on Telegram. Extremist networks rely on this “platform hopping” to stay online, taking advantage of the lack of coordinated moderation or shared tracking systems across companies.

Recommendations

This situation calls for a coordinated strategy that brings together advanced detection technologies and public education initiatives. The videos described in this Insight confront both the technical tools used to create and distribute synthetic propaganda and the social environments that allow it to circulate and influence audiences; any response must address both sides of the problem.

On the technological side, platforms are in urgent need of better tools for detecting AI-generated audio. Even though progress has been made in watermarking techniques, small embedded signals that help identify manipulated audio, their adoption remains limited, and the largest part of current moderation systems focus only on images and symbols, leaving synthetic speech largely undetected. Industry-wide standards for tracking and verifying audio deepfakes do not yet exist, and without shared protocols, tracing the original source remains difficult. Nevertheless, platforms could independently decide to collaborate with initiatives like the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), in order to build common detection systems rather than working in isolation.

Linked to the idea of collaboration, an equally important point to address is the need for cooperation between platforms. Extremist audio content that is removed from one site quickly reappears on another within hours, as previously stated. The creation of shared databases of known extremist material could make it harder for AI-translated propaganda to migrate across the internet. GIFCT’s Hash-Sharing Database (HSDB), operational since 2017, provides an established model: member companies share “perceptual hashes”, digital fingerprints of terrorist and violent extremist content, enabling rapid cross-platform identification and removal without sharing user data or original content. By looking at the legal domain, the Digital Services Act already requires major online platforms to address systemic risks, including disinformation and illegal content, which provides the lawful basis for a more structured cross-platform coordination.

However, while the Digital Services Act introduces transparency rules, it does not clearly define deepfakes, nor does it impose consistent obligations on AI providers, such as voice-cloning companies. Updating hate speech and counter-terrorism legislation to explicitly cover synthetic media would close the loopholes that are currently being exploited by extremist actors. Additionally, requiring transparency reports from AI voice-cloning services, similar to those that are already required from social media platforms, would also improve accountability.

Measures to counter the phenomenon could also directly involve the target audience by promoting stronger tools that help them recognise manipulated media and resist emotionally exploitative propaganda. Digital literacy programmes should teach users how deepfakes work and how extremist movements use them as recruitment tools. Schools, civil society groups, and platform safety teams could work together to design useful and accessible resources. Plans for an EU-wide AI literacy framework, expected in 2026, as stated by the European Parliament, offer a promising foundation for the creation of such counter-measures.

As a final recommendation, making instruments such as browser extensions and verification apps that detect synthetic audio easy to access, and integrating them into platforms by default, would provide an additional layer of defence against AI-generated extremism. These tools are already being developed, and wider deployment could help people examine suspicious content before sharing it.

—

Daria Alexe is a Master of Science student in Intelligence and Security Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. She has previously worked as a geopolitical analyst and holds a Double Bachelor of Arts in Global Governance and Political Science, as well as a Master of Arts in Prevention of Armed Conflicts and Terrorism. Her work focuses on international security, terrorism, and CBRN threats, conducting intelligence and geopolitical analysis on extremist networks and illicit activities in high-risk contexts.

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.