Introduction

When discussing social harms in online gaming spaces, the term “toxicity” frequently takes centre stage. It is often used as a catch-all phrase to describe a broad spectrum of harmful behaviours, ranging from casual trash talk to more severe offences such as hate speech, sustained harassment, grooming into offline violence, and the dissemination of violent extremist propaganda.

Alongside the rise of this term, “toxic gamer culture” has emerged as a related concept, referring to systemic issues within gaming communities, including the cultural normalisation and perpetuation of even the most harmful behaviours within gaming spaces. While these terms are widely used in discussions about online harm, they have often been treated in isolation—examining only a single facet of toxic behaviour or focusing on one specific consequence of toxic gamer culture. This narrow approach overlooks the complexity of online interactions, which are shaped not only by gaming culture but also by a range of social, psychological, and structural factors.

A recent research project led by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), funded by the Canadian Resilience Fund, and conducted with members of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN) offers a more comprehensive analysis of toxicity in gaming spaces as the first large-scale study to examine the intersection of gaming, social identity, gender, and geographic context (across seven countries, Australia, Canada, Germany, France, Indonesia UK, US). Via a comprehensive survey of 2,244 players and analysis of 15 million+ posts on gaming-related platforms, this study examines how toxic behaviours, gamer culture, and socio-cultural influences intersect to create vulnerabilities. In particular, the research explores how these vulnerabilities can be exploited by malign actors seeking to radicalise, recruit, and groom young people for violence. By adopting a multi-faceted perspective, this new study sheds light on the deeper mechanisms that enable harm in gaming spaces and highlights how gaming spaces operate as sites of potential exploitation. In this Insight, we will discuss some key findings from this project relating to the prevalence of harm and gendered norms and socialisation processes across geographical contexts.

Key Findings

Prevalence of harm

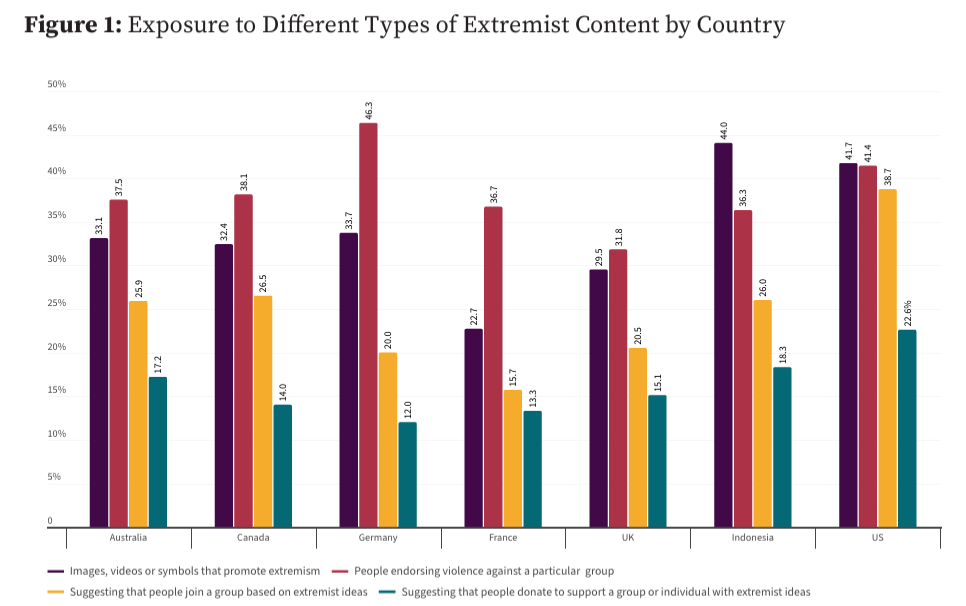

The study found that exposure to harmful content—including extremist material, hate-based discrimination, and harassment—is widespread in gaming spaces. Across the seven countries studied (Canada, the U.S., the UK, Germany, France, Australia, and Indonesia), a significant portion of gamers reported encountering such content. The kind of exposure varies, with most players reporting they encountered endorsements of violence against specific social groups (38%), images, videos or symbols promoting extremism (33%), or content suggesting they join extremist groups (25%).

Exposure to Harms Charting from Full Report.

Younger gamers (ages 18–28) reported higher exposure rates than older gamers (29–44), with men more likely to come across extremist content, while women were more frequently subjected to gender-based harassment. Misogyny was particularly prevalent, reinforcing toxic socialisation patterns that could lower resilience to radicalisation.

Geographically, exposure trends varied. In North America and Europe, far-right narratives and anti-LGBTQ+ hate speech were more commonly reported, while in Indonesia, exposure to violent jihadist extremist content was more pronounced.

The findings also highlight the normalisation of toxicity within gaming communities and the intersection of social identity factors—gender, nationality, and age—shaping vulnerability to radicalisation. While most of the respondents believe toxicity in games is unacceptable, 30% reported that they felt it was normalised. Males were more likely to find it acceptable than females.

Exposure to extremist sentiment can have significant consequences. First, individuals adjust to the norms of their culture (even across digital spaces). As such, the normalisation of extremist language in games puts players at risk of being socialised into extreme ideologies from the broader gaming community. The saturation of extremist language in gaming spaces also makes this environment more vulnerable to direct forms of exploitation, such as propaganda dissemination and recruitment efforts by organised groups.

Cross-cultural findings

While extremist content in games has been preliminary researched and discussed within a US or UK context exclusively, it is prevalent across jurisdictions. Looking across geographical contexts, Indonesia (44%) was found to have the highest proportion of respondents exposed to images, videos, or symbols prompting extremism, while France (22.7%) had the lowest. Germany (46%) led exposure to content endorsing violence against specific groups. However, the US had the highest rates of encountering content suggesting they join extremist groups (38%, as compared with 15-26% in the other countries). Further country-level differences are discussed in the full report.

In a forthcoming journal article, we also analyzed our survey data to assess the overall resilience of players against extremism and violence. In doing so, we found that the more complex a player’s “gamer identity” is – how well it reflects their many identity facets of age, religion, nationality, gender, and ethnicity – the more resilient they are against overall extremist approaches. Building communities that support diverse, complex gamer identities is key to supporting resilience; promoting singular, monolithic ideas of a homogenous “gamer identity” is not. Likewise, helping to create online gaming interactions across people from different backgrounds fosters resilience. We also found that a willingness to stand up for other people being targeted by hate online improves resilience against violent extremism. Conversely, supporting toxic hate and harassment-related beliefs and behaviours reduces that bulwark.

Gendered norms and socialisation

From socialisation to radicalisation, this research also highlighted the overlapping importance of identity, exposure, and experience. Gendered norms play a prominent role in shaping socialization within gaming spaces, with male respondents reporting that they were more likely to engage in or be exposed to extremist content, while women face higher rates of harassment and exclusion. Female respondents were also more likely to deem “toxicity” in games as unacceptable (68%) than males (50%), and extremist content in games specifically (72% females, 63% males), reiterating gender differences in the experiences of harmful and hateful content in these spaces.

Drawing on previous work in this space, we know that this kind of hostile environment can normalize misogyny, fostering an ecosystem where extreme ideas become more accepted over time. Additionally, every prior study to examine misogyny and support for violent extremism or terrorism has found a clear correlation. Prolonged engagement in this kind of environment can contribute to a socializing effect in which players are gradually exposed and indoctrinated to more harmful and extreme ideologies that promote violence.

What Can We Do?

The gaming industry is not equipped to adequately prevent, detect, or moderate extremist content in games. While the specific kinds of tools and strategies will likely need to be tailored to each particular organisation, studio, or gaming surface, there are commonalities across the space, making industry-wide conversations about these topics critical. Taking this into consideration, there are several strategies that companies could adopt. Building on recent guidance from the GIFCT Gaming Community of Practice Working Group, including threat one-pagers and a new prevent-detect-react framework, these include:

Prevent

Set policy

Step one is to concretely prohibit the use of terrorist and violent extremist language, iconography, and sentiment in gaming spaces. Several game-adjacent platforms have already specifically prohibited these actions in their games (e.g., Activision Roblox) whereas other studios do not yet directly note extremism in their terms of service or code of conduct. Clear community guidelines, rules that are well-defined and consistently enforced, are a necessary foundation for both community reporting and establishing cultural norms for gaming communities.

Build community support models

The role of community management is critical in shaping community norms. Community management roles are consistently underfunded, undervalued, and excluded from trust and safety discussions. However, frontline moderators and community managers play a pivotal role in maintaining safe and positive (and fun) spaces in gaming and digital communities. Many of these digital community leaders report feeling underprepared to handle the complexities of managing online spaces. There is currently a dearth of preventative approaches that include educational support and training for community leaders in games, such as community managers (one notable exception being this new initiative from Discord).

Red teaming for games

Red-teaming is a term originally from info/cyber security used to describe efforts to exploit one’s own products via internal adversarial testing in order to develop mitigation measures (see previous GIFCT outputs on red teaming against terrorist and violent extremist actors). In gaming surface contexts, this would come in the form of built-in checks during the game design process around the leveraging of the content and community by extremist groups. Similar to sensitivity reads for content warnings and accessibility reads to ensure accessibility, we suggest a read dedicated to detecting vulnerabilities across both content and technical capacities in the game, and then make adjustments if needed.

An example of what red-teaming can do can be seen in the marketing of Wolfenstein 2 (Bethesda). Wolfenstein 2 is a game whose content could have been leveraged by extremists for propaganda; however, the developers got out in front of that process with a marketing campaign that pushed a strong counter-narrative. This campaign, which has since come to be known as the ‘Punch a Nazi’ marketing campaign, was hugely successful in preempting the leveraging of their content and demonstrating how marketing efforts can shape community expectations – and helping to promote the end product. Failing to do so, as Far Cry V did and subsequently saw dramatic exploitation of in-game content by white supremacist groups, also carries consequences.

Other prevention approaches include improving awareness of online extremist and terrorist exploitation of games for players, parents, and studios alike; designing influencer campaigns to help promote positive in-game behaviour and norms; and partnering with mental health and psychosocial support groups to help guide intervention, mentorship, and pro-social in-game behaviours. These are detailed in the Prevent, Detect, React framework, as well as in new prevention guidance (Implementing Positive Gaming Interventions: A Toolkit for Practitioners) from our research project team.

Detect

Basic moderation detection strategies, such as machine-moderated word lists of hateful and extremist terms, are the bare minimum for multiplayer online games; however, not all games even have these tools, and they rely solely on player reports.

While detection efforts have grown in the last few years, there is still room for improvement. For example, despite some automatic censoring measures implemented by Steam to filter out offensive language, it is still easy to find posts that convey hateful or extremist sentiments. Additionally, while these detection systems may partially censor slurs and other keywords, often the underlying intent of a message is only apparent to trained human readers, highlighting the limitations and strategic obfuscation of automated moderation systems. Linguistic challenges across geographics – different languages with inadequate ML tooling – also hinder machine-based approaches. Improving both machine moderation – via image, voice, and text detection – as well as trust & safety team training and easy user reporting tools that can be used in-game are critical. Equally, sharing signals and new techniques being used by organised threat actors across platforms and services should be prioritized: the GIFCT Hash Sharing Database and Tech Against Terrorism’s Terrorist Content Analytics Platform do this in part but can be improved. Free or affordable tools to help smaller studios and game creators keep their games safe should also be prioritised via initiatives like ROOST, a new set of AI open-source safety tools.

React

Many games have an integrated player reporting (sometimes called user reporting) system where players can submit reports based on violations of the terms of service or code of content, which can include extremist content. However, estimates suggest that less than 10% of the active player base will submit reports. In our research, we found that while 90% of players know how to report on one platform, only one in three (36%) know how to report across all the platforms they use. And, worryingly, a similar share (33%) do not feel they are heard when they file a report. Easier reporting systems that provide feedback loops to users are a must, along with providing users categories to flag extremist, terrorist, or violently targeted hate attacks.

We also know anecdotally that user reporting is necessary but is insufficient in and of itself to address platform, game, or service-level community norms. This does not mean we should not include these systems (we absolutely should), but rather we should consider other potential reactive approaches. For example, transparent feedback pipelines for the reporters and offenders. Research has found that when offending players are given feedback, there are large reductions in repeat offending behaviour.

The limitations of reactive approaches also reiterate the need to prioritise the prevent and detect approaches.

Conclusion

The intersection of online games, offline identities, and cultural norms can create grounds for the reinforcement of toxic behaviours and the propagation of extremist ideologies, leading into targeted violence. The normalisation of these actions, coupled with the reinforcement of misogynistic stereotypes and harassment in games, highlights a pressing need for interventions that can address these dynamics. Understanding the scope and consequences of extremist behaviour in games and scaling up trust and safety efforts to prevent, detect, and react to it is crucial for fostering positive player experiences, protecting vulnerable users, and ensuring the long-term health of gaming communities. A well-designed trust and safety approach that includes moderation and clear content policies, alongside support for moderators and their communities, will not only minimize harm but amplify the positive experiences within gaming communities.