The Link Between Combat Sports and PMC Wagner

With a worldwide consolidated fan base, Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) has grown in popularity in Russia and the ex-Soviet countries since the early 2000s, driven by the success of local promotions, international stars like Fedor Emelianenko, and the rise of dominant fighters from regions like Dagestan and the Caucasus, such as Khabib Nurmagomedov. Government support and increased media coverage have further cemented MMA’s status as one of the most popular sports in the region. Due to their cultural importance (historical, cultural, and socioeconomic), combat sports have become an extremely thriving element for homegrown extremisms in Russian society. But as MMA has grown in popularity, it has presented serious security issues, as extremist organisations use it for recruiting and propaganda. The combat sports environment has become a breeding ground for various types of violent extremism across the ideological spectrum, from jihadism to the extreme right. Among the most proactive organisations, PMC (Private Military Company) Wagner has established a recruitment system based on a network of gyms and sports centres specialising in combat sports. PMC Wagner enrols fighters with promises of financial rewards, career opportunities, and shared ideological views such as nationalism or patriotism. For fighters from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, joining Wagner offers a lucrative alternative to pursuing an uncertain career in professional sports.

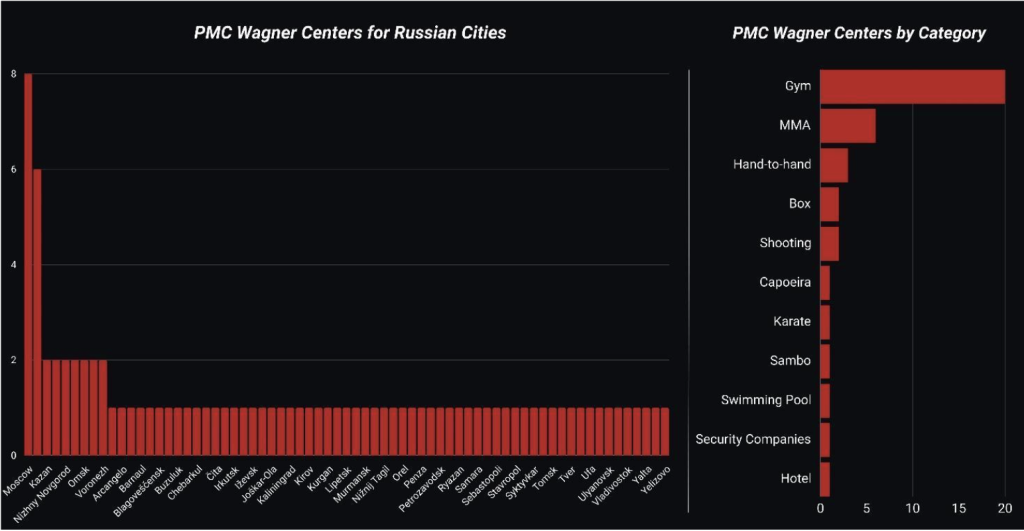

This Insight examines the recruitment supply chain developed by PMC Wagner, which exploits the combat sports environment and analyses the key elements influencing its operation. Our research reveals how PMC Wagner has used combat sports to build a recruitment, advertising, and promotion system. Through an in-depth analysis of the pro-Wagner online ecosystem, particularly on Telegram, we partially reconstructed the recruitment supply chain and observed the connection between Wagner and the combat sports community. This link is evident in the information disseminated within the ecosystem, which reaches recruitment centres, mainly gyms and sports facilities. From this initial data collection (Figure 1), a portion of the Wagner recruitment network appears to reflect the deep-rooted cultural importance of combat sports in Russian society.

Figure 1: Summary of the data collected within the main official Telegram channel of the PMC Wagner.

It is important to note that the recruitment network setup is a typical bottom-up system. The gyms shared by the Wagner channels are not centres built by the PMC but specialised and already active sports centres and gyms that are well-known in the environment and, above all, have pre-existing advertising systems. In practice, Wagner exploits the networks that each centre had already implemented. These centres aligned themselves with Wagner for ideological reasons, such as ultranationalism and right-wing extremism, and formed a significant part of the recruitment network.

Social Networks Analysis

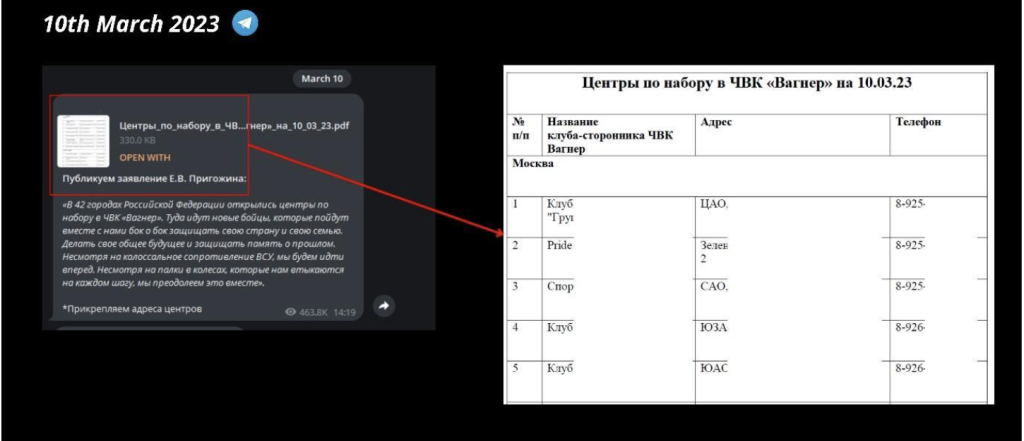

On 10 March 2023, the official Telegram channel of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the now-deceased founder of Wagner, published a PDF with a list of fifty-eight recruitment centres by city and address, with a telephone reference. From this document, it was possible to extract the names of the gyms involved in the group’s recruitment. Furthermore, the social media of the gyms were examined to conduct a more in-depth and evidence-based investigation. The first evidence that emerges from the study is the centrality of MMA competitions and the role of each fighter.

Figure 2: Screenshots taken from Prigozhin Telegram channel, with the PDF of the recruitment centres.

This raises the question: What are the key events where recruited forces can be best utilised? The answer lies in tournaments—gatherings where offline and online propaganda converge. These events offer opportunities to recruit additional manpower and expand the pool to include fighters not directly affiliated with PMC Wagner.

On the one hand, we observe how Wagner practically delegates part of the recruitment to the Wagner centres, setting them up as megaphones of pro-Wagner and pro-violence propaganda; on the other hand, we note that the social media of these centres become more active during national and international tournaments. During these events, the fighters and Wagner centres’ social media profiles maximise their communication and promotion activities. Wagner-linked gyms and fighters cross-promote sporting and paramilitary events (Figure 3). Fighters’ participation in tournaments helps identify those who align ideologically or need financial stability.

Figure 3: Screenshots taken from pro-Wagner gyms, promoting the Russian MMA Federation (on the left) and encouraging recruitment (on the right).

The Insight’s second piece of evidence shows how pro-Wagner events are primarily promoted via MMA contests. Wagner uses MMA competitions as forums for propaganda. Wagner-affiliated fighters participate in these events, which receive widespread social media coverage, expanding the group’s audience and impact. PMC Wagner has established an online and offline recruitment network that is infused with pro-violence societies and extremist ecosystems such as the far-right, ultranationalists, and also jihadists. It is interesting to note that despite these conflicting ideologies, Wagner’s recruiters exploit the economic needs of already violent and radicalised subjects by attracting them with the prospect of leading an ‘adventurer’s life’. This narrative is recognisable in Prigozhin’s movie production, which aims to mythologise the figure of the mercenary Wagner. The extremist ideology becomes a merely attractive and functional tool for recruiting new mercenaries.

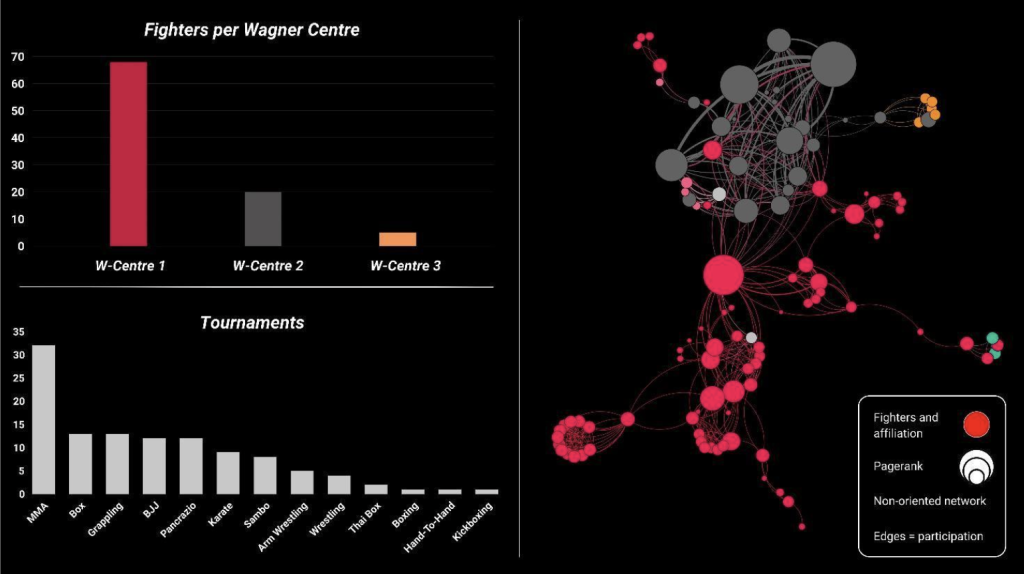

Once it was established that the competition and fighters are the key elements of the propaganda and that the centres act as the supporting infrastructure of the system, a one-mode social network analysis was conducted (starting with the two-mode involving fighters and tournaments), we focused exclusively on the fighters to identify the most active participants in combat sports tournaments, both online and offline, and to determine which Wagner-affiliated centre they were associated with.

Figure 4 illustrates the main cluster of the Wagner-related fighter network. The size of the nodes (representing fighters) indicates their PageRank level. This measure determines the relevance of each node based on the number of incoming relationships and the importance of the connected source nodes. Generally, the assumption is that a node’s importance is influenced by the pages linking to it. In other words, PageRank reveals the popularity of specific nodes within the network and their capabilities to interact with other important (popular) nodes.

The social network analysis reveals that more than 60% of the fighters come from the same Wagner centre (Figure 4: W-Centre 1). One fighter participated in multiple tournaments and served as a link to several other gyms.

Figure 4: Summary of the data collected on the active fighters, members of Wagner centres and those involved in Russian and international tournaments from 02/2022 to 06/2023.

Although it might seem that W-Centre 1 and the fighter with a high PageRank are community leaders, this would be a misunderstanding. Given the structure of the Wagner recruitment system and its methods, the supply chain is leaderless and horizontal, relying on physical presence at tournaments rather than centralised leadership.

Conclusion

The rising popularity of MMA in Russia, driven by a combination of historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors, has given rise to significant security concerns. This study reveals how PMC Wagner has exploited the combat sports landscape for recruitment and propaganda, establishing a sophisticated network that merges ideological indoctrination with financial incentives. The network allows Wagner to attract individuals with advanced combat skills, mobilise them efficiently, and extend its influence within Russia and internationally. The analysis highlights the pivotal role of MMA tournaments in PMC Wagner’s recruitment efforts. These events serve as crucial aggregation points where offline and online propaganda converge, allowing Wagner to attract recruits and expand its influence. Fighters participating in these tournaments gain visibility and act as bridges to other gyms, facilitating the spread of Wagner’s message and recruitment drive. While it is noteworthy how Wagner’s leadership has capitalised on the popularity of the combat sports arena and selected allied centres, understanding the full impact of this recruitment strategy requires on-the-ground insights. This deeper knowledge would provide a clearer picture of how these alliances contribute to Wagner’s recruitment success and overall operational reach.

Tech companies can play a significant role in disrupting the PMC Wagner recruitment supply chain by monitoring, regulating, and taking proactive actions on their platforms, where much of the group’s recruitment and propaganda efforts take place. Platforms need to invest in AI and machine learning systems capable of identifying extremist content and recruitment patterns. These systems can analyse not only text but also images, videos, and metadata to detect signs of extremist activity, such as coded language, symbols, or recruitment narratives embedded in content. These automated systems should be complemented by human moderators to review flagged content. For instance, many pro-Wagner narratives are driven by prominent MMA figures, influencers, or fighters who act as brand ambassadors for the group. Removing these influencers from platforms like Instagram, Telegram, and VK will help dismantle their digital recruitment network. Moreover, real-time monitoring is important for dynamic threats such as extremist recruitment. This could include tracking trending topics and discussions that might indicate recruitment efforts or coordinated campaigns. Platforms can also set up alert systems to notify moderation teams of potential flashpoints or spikes in extremist activity, allowing for a faster and more targeted response to emerging threats.