Introduction

In today’s digital age, falsehoods travel faster than real news and garners instant traction. Through well-curated dis and misinformation campaigns, mischievous online actors can exploit a particular community’s emotions and cognitive biases to shape their perceptions around particular events. Unfortunately, online misinformation campaigns are now a standard part of any modern political upheaval.

In August, Bangladesh witnessed a flood of dis and misinformation campaigns by online Hindutva groups in the wake of former Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s ouster and the Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus’ take over as the head of the new interim government. During the transition period, political uncertainty followed as police, involved in alleged torturing and shooting at student protesters, went on strike and withdrew from the streets in anticipation of reprisal attacks. The unrest that followed due to the law enforcement vacuum in a rapidly evolving political situation left people vulnerable to fake news. This Insight examines online Hindutva groups’ use of X to exploit Bangladesh’s political unrest by fabricating and subsequently employing sensationalist claims, doctoring images and disseminating old videos of unrelated events. Unfortunately, the misinformation campaigns not only created an atmosphere of intimidation for Bangladesh’s beleaguered Hindu community, but also created challenges for the new caretaker set-up.

Hindutva-peddled Fakes News, Rumours and Conspiracy Theories

The political and information vacuums following Hasina’s resignation allowed angry protesters and criminals to ransack offices, residences and properties of the Awami League’s (AI) Muslim and Hindu leaders. However, online Hindutva groups framed attacks on Bangladeshi Hindus as communal rather than political in a bid to stoke sectarian tensions. They pushed lurid and unverifiable claims and proliferated doctored photos and footage on social media to create an impression that Hindu genocide is occurring in Bangladesh.

The social media monitoring tool, Brandwatch, geolocated most of the accounts peddling misinformation campaigns and malicious propaganda about Bangladesh’s political developments to those based in India.

As the largest religious minority, Hindus constitute 8% of the Muslim-majority 170 million population in Bangladesh. Historically, Bangladesh’s Hindu community has supported Hasina’s party for its secular credentials, viewing it as the vanguard of its religious freedom and communal interests in the country. Soon after Hasina’s dismissal, unverified claims of 500 attacks against Bangladeshi Hindus across 52 districts spread through social media platforms, many of which were picked up by some mainstream Indian news channels as well. In Bangladesh’s uncertain political environment, differentiating religious from political became extremely difficult. Nonetheless, online Hindutva groups deliberately framed Bangladesh’s political developments through a narrow communal lens to push the Hindu victimhood narrative. However, this is not to deny Bangladesh’s past communal fault lines where Hindus have been victimised when a government fell. For instance, Hindus were disproportionate victims of the 1971 Independence War, in which up to three million people were killed.

Hasina is a close Indian ally, and Hindutva groups see her fall as a strategic loss. She portrayed herself as the protector of Hindu and Indian interests in Bangladesh. That is why Hindutva groups unleashed a fervent propaganda campaign to generate the notion that in post-Hasina Bangladesh, “Islamists” will be on the loose to kill Hindus. This fear-mongering and racist disinformation seeks to demonstrate that Bangladesh still needs Hasina. Otherwise, the country will become a so-called Islamic State.

On one hand, such misinformation campaigns have heightened fears of Bangladesh’s Hindu community amid an uncertain political atmosphere. On the other hand, they are creating challenges for Yunus’ caretaker regime, which is trying to navigate Bangladesh through one of the most critical phases of its history. Hindu nationalists are portraying Hasina’s ouster as a tragedy for Bangladesh’s democracy, conveniently overlooking her 15-year authoritarian rule to deny agency to a bottom-up student movement.

Using Hashtags to Circulate and Sustain Disinformation

Searching #Bangladesh on X unveils a slew of malicious propaganda campaigns with sensationalist claims, such as the persecution against Hindus in the form of genocide, mass killings and rapes of Hindu women after Hasina’s ouster. Graphic videos of doubtful veracity and pictures of unrelated events were shared about the fate of Bangladeshi Hindus. Online Hindutva accounts deliberately mischaracterised the political violence in Bangladesh as communal or overexaggerated it to cater to their right-wing Hindu nationalist community in India.

Subsequently, notable Indian X accounts, including social media personalities, stepped in and reshared these narratives for wider circulation and dissemination. These accounts were promoting Islamophobic content, and promoted the unfounded notion of Bangladesh’s takeover by Islamists after Hasina’s ouster, where jihadists will have a permissible environment while the Hindu minority will suffer. These accounted for misquoted incidents of political violence against Bangladeshi Hindus as religiously motivated to strengthen their narratives. Some of these accounts are massive in their size and outreach and were later picked up on other social media platforms like Facebook.

Hashtags such as #HindusAreNotSafeinBAngladesh, #SaveHindusinBangladesh, #HindusUnderAttack and #allEyesOnBangladeshiHindus were used to sustain and perpetuate false narratives and rumours. Some of the videos and images shared using these hashtags went viral, drawing millions of likes and reshares. This was done to reinforce the perception that Hindus are a besieged community in Bangladesh and justify the otherisation of Muslims in India.

Figure 1: Hindutva protest outside UK’s Parliament against Hindu genocide in Bangladesh

Bangladeshi Hindu Toolkit and AL Student Wing’s Leaked WhatsApp Message

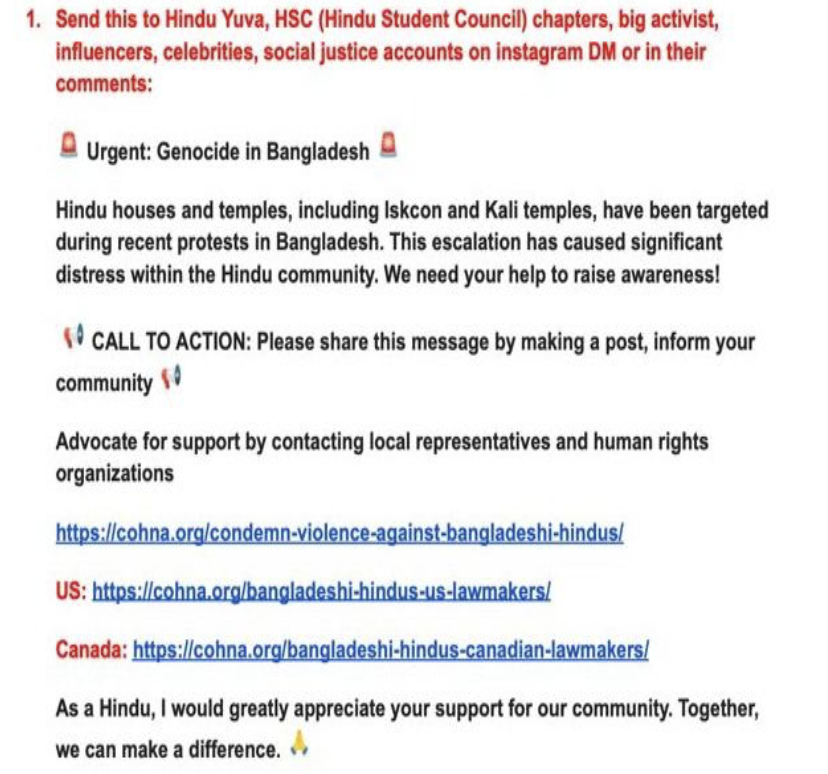

A document, titled the ‘Bangladeshi Hindu Toolkit,’ exposed by Bangladeshi academic and dis/misinformation expert, Farhana Sultana, revealed the extent of the meticulous planning and efforts invested by Hindu far-right groups to spread misinformation. The document detailed instructions and an action plan for online campaigns, protest demonstrations and vigils in important Western capitals by alleging that “Hindus are facing genocide” after Hasina’s fall in Bangladesh (Figure 2). The document provides in-depth instructions on narrative-building and creating posts and placards for which overexaggerated figures were fed. At the same time, it also urged Hindu far-right leaders to reach out to media and human rights organisations in the US, UK and Canada, as well as meet politicians and lawmakers in Europe and the US to sway their opinions.

Figure 2: An image of the “Bangladeshi Hindu Toolkit” document circulating on various social media platforms

Figure 3: A montage of pictures showing far-right Hindu activists demanding justice for Bangladesh’s Hindu community

Likewise, a leaked WhatsApp message from AL’s student wing, Bangladesh Chhatra League, revealed that it was working in tandem with online Hindutva groups to sow chaos. The leaked message disclosed plans by some elements of the Bangladesh Chhatra League to sporadically target Hindu temples in Bangladesh in false flag operations to reinforce the narratives of communal violence against Bangladeshi Hindus. Furthermore, they also conspired to participate in protests, posing as victims of their own violence to amplify Hindutva propaganda. Reportedly, the Bangladesh Chhatra League planned to carry out organised violence against minorities from 14 August to stage a coup on 15 August to reinstall Hasina.

Misleading Narratives, Doctored Images and Unrelated Videos

By now, fact-checkers have exposed and debunked numerous misleading posts and false narratives of online Hindutva groups promoted on X and other social media platforms.

To showcase attacks on Hindu properties, Hindutva accounts mass circulated a video of a burning house, which they falsely claimed belonged to Bangladeshi Hindu cricketer and the Test team captain, Litton Kumar Das. The post received over a million views and several shares with identical claims. However, the house actually belongs to a Muslim cricketer and a former captain of the Bangladeshi team, Mashrafe Mortaza, who was an AL lawmaker.

Figure 4: Mashrafe Mortaza’s house set on fire by angry protesters

Likewise, some Hindutva accounts on X asked India to prepare for a mass exodus of Bangladeshi Hindus escaping persecution. Some even suggested Indian military intervention to save Bangladesh’s Hindu community. A Hindu right-wing organisation, Vishwa Hindu Parishad, appealed to the ruling Hindu nationalist Bhartiya Janata Party to prevent “jihadis” posing as refugees from entering India. One video claiming to show a jihadi mob attacking Hindus was actually taken during student protests against the civil service quota by AL supporters. Such narratives have also falsely propagated that Islamic fundamentalists will rule Bangladesh after Hasina’s resignation. As a result, India tightened border controls by increasing patrols and monitoring. Though hundreds of Hindus arrived at the Indian border requesting to cross, it was nowhere near the exaggerated claims circulating on social media platforms.

Another video circulating on X malignly maintained that angry protesters had ransacked the Hindu Navagraha Temple in the southeastern Chattogram district. However, the footage was of a burning police station, not the temple. Republic TV, one of India’s most-watched mainstream news channels, also broadcast this misinformation.

Figure 5: Awami League office torched by protesters behind Navagraha Temple

Impact and Analysis

On 9 August, in reaction to misinformation spread by online Hindutva groups about developments in Bangladesh, Hindu Raksha Dal, a right-wing Hindu organisation, attacked Muslim workers living in shanties near a railway station in India’s Ghaziabad district. They accused them of being Bangladeshi nationals who were targeting the Hindu community. Reportedly, a mob of 13 vigilantes carried out house searches and inquired residents if they were Hindus or Muslims. Thereafter, Hindus were spared, while Muslims were beaten brutally.

Figure 6: A right-wing Hindu activist ransacking tents belonging to Muslim residents in Ghaziabad

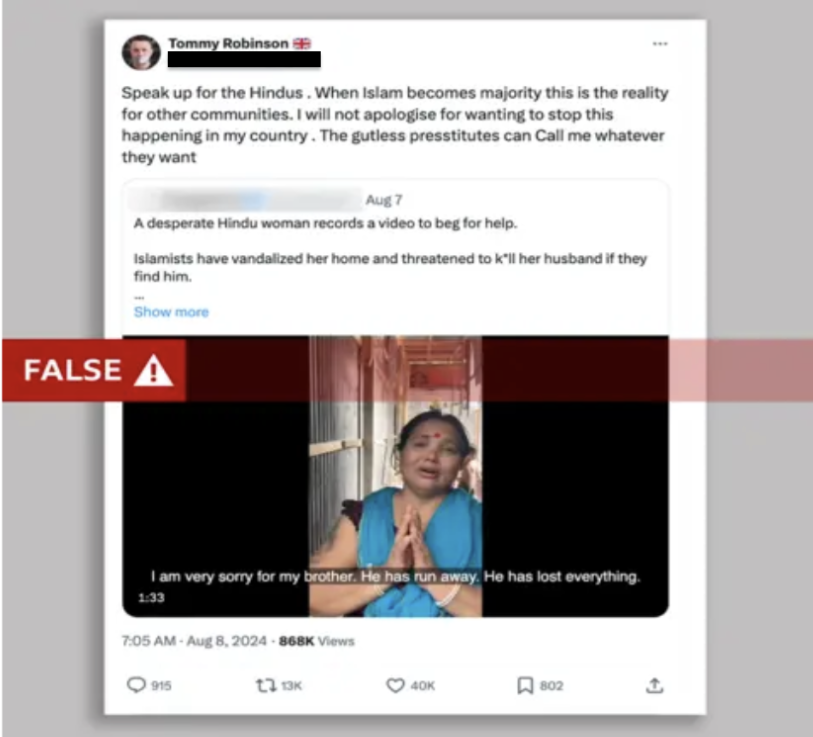

The UK’s most prominent far-right figure and anti-Islam campaigner, Tommy Robinson, has reshared these Hindutva groups’ misinformation campaign, claiming that a Hindu genocide is taking place in Bangladesh. In an X post, he wrote, “Speak up for Hindus. When Islam becomes majority, this is the reality of other communities. I will not apologise for wanting to stop this happening in my country. The gutless presstitutes call me whatever they want.”

However, this is not the first time that Hindutva groups’ misinformation have found a receptive audience in the UK. Such propaganda campaigns have fueled social and communal tensions during the 2022 Muslim-Hindu civil unrest in Leicester. Hindutva groups in India escalated tensions on the ground in Leicester by spreading dubious claims through X hashtags like #HindusUnderAttackinUK and WhatsApp forwarded messages.

Figure 7: Picture of a Hindu woman seeking mercy from angry mobsters shared by Tommy Robinson on his X profile

Concluding Recommendations

In fluid political situations, misinformation campaigns can easily sway public opinions and perceptions. On one hand, such malicious campaigns cause real-world harm. On the other, they undermine the reputations of social media and big tech companies. The arrest of Telegram founder Pavel Durov in France underscores the growing frustration of governments with various social media companies whose platforms have been used as destabilising tools. Telegram has become a digital safe haven and a den for violent extremist groups of all hues and stripes. Keeping in view what happened in Bangladesh, social media companies need to invest more in their content moderating capabilities with strong regional and local linguistic capabilities. Artificial Intelligence-enabled moderation algorithms are not sufficient to counter the growing risk of misinformation. Following the 2021 Christchurch mosque attack in New Zealand, content moderators and linguistic experts were hired. However, during the recent rightsizing efforts in tech and social media companies, the first axe fell on content moderators.

At the same time, social media and tech companies should forge collaboration with third-party actors like local content moderators and organisations with political and social knowledge of different regional countries. The tasks of such organisations should be to flag malicious content and hate speech in local dialects, especially during political, religious and social turmoil. Critically, some of the harmful material and hate speech propagated in local and regional languages stay on different social media platforms for longer durations and act as inflamers and fomenters in crisis situations. Linguistic capabilities for content moderation are necessary but not sufficient to prevent infodemics. People with regional expertise will help companies with a nuanced and contextual understanding of local developments in countries like Bangladesh to remove harmful and malicious content. Finally, in rapidly evolving political and communal situations, adding warning labels to misleading content is not going to be sufficient, such material should be removed or blocked to avoid the misuse of social media platforms as agent provocateurs.

Abdul Basit is a Senior Associate Fellow and head of the South Asia desk at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. His primary research focus is on South Asia’s insurgent, militant and religious movements and groups.