Introduction

Swatting is named after the ‘Special Weapons and Tactics’ groups of law enforcement officials in the United States – known by the acronym ‘S.W.A.T.’. The major goal of a caller who originates these fictitious disasters is to generate a massive law enforcement response to an unsuspecting victim. In many cases, these false calls are aimed at a country’s localised educational system such as its schools, and can be cross-border generated. Swatting is effectively an attack on a nation’s political system and has several nexus points to global violent extremism and terrorism today.

The paradox about a Swatting call is that there is not an actual attack – considered legal in many jurisdictions – since this type of communication is not an actual posed threat. Unlike a called-in bomb threat, the Swatting caller is not making a threat but rather relaying information about a fictitious threat and its ongoing fake hazards. It does not state there will be an attack at a school but rather claims that the attack is already occurring – when, in fact, it is not.

Should Swatting be Considered Terrorism?

The answer today is largely ‘maybe’ or ‘depends’. And much of that is tied up in the global debate over what the definition of terrorism really is. Brett Raffish made many salient points on this – and the mission of GIFCT to disrupt both terrorist and violent extremists (VEs) – in his 2021 Insight. Can terrorists and VEs generate terror, even death by others, by simply making a phone call or generating a deep fake video? The answer to that question is ‘yes’.

The aim and result of a Swatting call is two-fold: to exhaust local public safety resources and create novel real-world life safety hazards; and to terrorise the individuals and organisations for whom the Swatting call is targeting. Failing to protect and prevent the adverse impacts from Swatting calls and continuing to respond to them without any countermeasures for validation, de-escalation, and recovery is a recipe for disaster. This Insight will analyse the threats from Swatting – potentially tracked from terror groups – and their global hazards.

What may have started decades ago as a revenge act between school-age rivals, Swatting calls are now part of criminal acts. Local law enforcement groups – the primary first responders to Swatting calls – are already cognisant of and countering additional hazards, such as:

- Testing/Probing local response capabilities: Many times, the person making the Swatting call monitors the incident response as it unfolds.

- Misdirection of resources: This affects already-lean local law enforcement groups who are required to respond to one geographic area while a real attack occurs elsewhere. Emergency Responders are now trained to view attacks as potentially complex and coordinated.

- Generating response fatigue: Repeated Swatting calls to the same location (sometimes multiple calls in the same day) will generate mutual aid requests for force multipliers and additional resources needed to investigate the Swatting calls.

There is evidence that foreign actors – with possible links to foreign terrorist organisations – are capable of generating large-scale Swatting attacks simultaneously across multiple jurisdictions. While many Swatting calls have their origin in one country, the actual Swatting call is made by an individual or group in another country. The initial idea of harming someone else by sending law enforcement to their location is being actualised via the dark web and cryptocurrency for payment methodologies; both are certainly the lair of extremists and making Swatting calls is an easy and apparently risk-free funding source for them. Swatting calls have been prompted by real-world active assailant attacks and may also be linked to potential election interference.

The threat landscape is only becoming more complex and challenging for local communities to protect and prevent adverse impacts from occurring. This is the aspect of moving the curated threat intelligence gathered through international resources, passed on to homeland security analysts and counter-intelligence experts, and finally to local emergency management professionals, including but not limited to law enforcement officials. Most governments are failing at this last transfer point when it comes to immediate interdiction and disruption for real-world life safety threats. While there may be collaboration and coordination on actual life safety threats to individuals and organisations in one country from a real-world attack by a foreign national or group, the agility and frequency of Swatting calls do not fit the standard protocols and practices of the current counter-intelligence model. The technology to create harm is outpacing the protections needed to thwart such attacks. Governments are far behind the criminals, and the public continues to bear the risks.

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

It is not only individuals but organised extremist groups that can use generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). The threat may have its origin (including targeting) in one country, and then the execution of the Swatting call may be made by an extremist group in another country. Swatting calls can also be carried out entirely in one country by a single individual, aimed anywhere in the world. US intelligence sources note that Swatting calls can fit into any extremist group’s existing disinformation/misinformation campaigns through:

- The spread of false or misleading images to alter public perception of facts, disseminate violent extremist media or messaging, and support false narratives.

- Impersonation of humans to gain unauthorised access to sensitive information, spread disinformation, and/or convince victim(s) to take specific actions based on false narratives, using for example:

- TEXT- To enhance, amplify, and legitimise violent extremist messaging with grammatically correct language in multiple languages for dissemination to a global audience.

- VIDEO- To create customisable AI-generated features that recite text-to-voice as well as text-to-video features. AI-enabled video alteration technology includes functions that enable face swapping or overlaying facial features onto those in already existing videos.

As GenAI moves more into realistic video and audio, what is fictitiously reported as a real attack at a school becomes something a human emergency response dispatcher in a call centre (where these calls are predominately directed) cannot easily dismiss as a false flag operation. The entire audio of a Swatting call can be generated in an untraceable AI-originated voice for free, and with a few more clicks, a realistic video can be produced, as well. Both the 911 system in the United States and the 999 system in the United Kingdom have been receiving internet-based calls and now can also receive video calls intended for sign language users: these can provide additional elements of critical real-time intelligence for incident management. However, this enhanced capability comes at a cost: the need to keep up with (and counter-attack/disrupt) the technology of fictitiously created incidents generating misinformation and disinformation.

What may be a block to implementing anti-Swatting technology and shifts in policies/protocols for response is that many jurisdictions may not recognise Swatting calls as being actual criminal activity. Their view of ‘better to be safe than sorry’ discounts the potential hazards which Swatting calls can and do generate. While the caller is not making an actual threat – they are diverting resources, causing mental and health stress/trauma, and rendering government services ineffective. Swatting calls have been treated as a nuisance – even considering them misinformation/disinformation does not raise the threat level for local law enforcement actions and reactions. The genesis to interdict and/or disrupt criminal activity generally requires a crime to be (or about to be) committed. In the US (and most likely other countries), the factors which qualify an “expressed or implied threat” for suspicious activity reporting (SAR), are described as “communicating a spoken or written threat to commit a crime that will result in death or bodily injury to another person or persons or to damage or compromise a facility/infrastructure or secured protected site.” Swatting is technically not making a real or even a fabricated threat. It is falsely relaying an imagined threat. Only recently did the FBI start tracking Swatting calls.

Yet, Swatting can have the same effects as a real attack: massive police and other first responder movement towards a potential threat, which can then have its own risks and hazards as well. Some law enforcement officials believe that ‘out of an abundance of caution’ they need to respond to Swatting calls as if it was a real incident: even if they receive confirmation from the Swatting call victim – such as a school – that no threat exists. That mentality wastes valuable resources, puts people at risk of life safety hazards, and demoralises both the responder and the intended target.

Shift towards Anti-Swatting

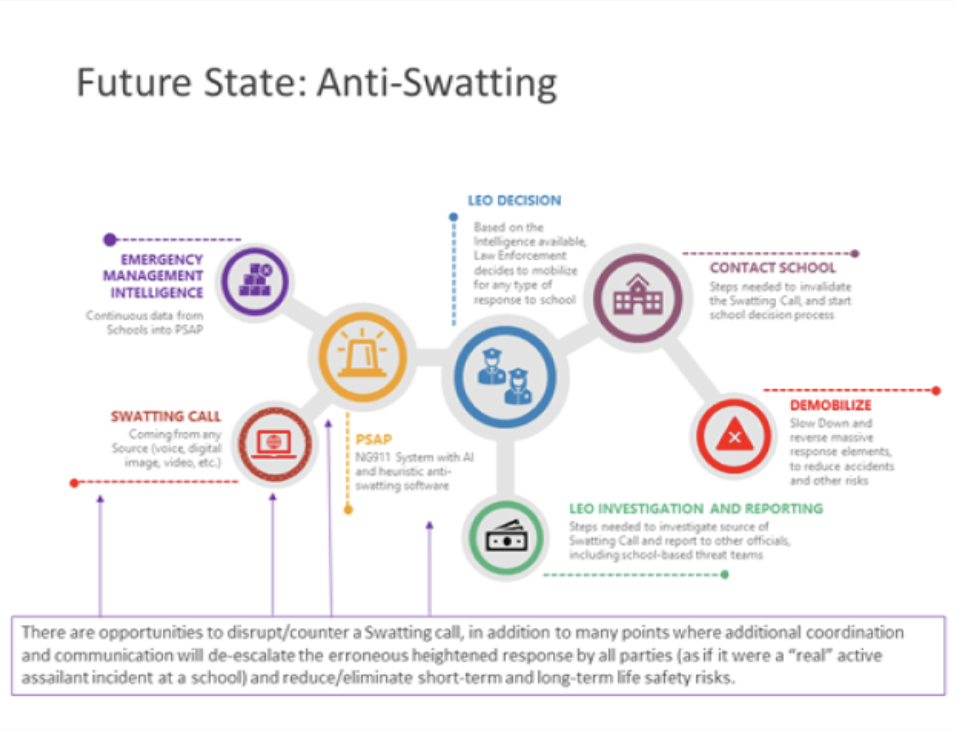

Research is now underway in phases to work through how to interdict and disrupt the adverse impacts of Swatting calls (including those made through texts and videos). The next step in this process is to focus on sets of solutions for the Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP). These are the locations and systems that receive these calls, texts, and videos to then dispatch first responders. Following an emergency management agile and continuous improvement process of planning, organising, equipping, training, and exercising for this problem statement – both in these phases or modules and as a complete system – researchers will eventually produce a universal model, which can be implemented in any country.

Figure 1. Future State: Anti-Swatting. Source: Barton Dunant. Copyright 2024. Used with Permission.

The challenge of Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) calls has been the reduced capability to filter and to trace the true geographic location of the caller, as compared to traditional landline calls with caller ID. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) add additional complexity to this challenge. PSAPs cannot arbitrarily refuse inbound VoIP calls, as many households no longer have landlines, and many cellular carriers use a mix of radio bandwidth and internet use for their growing capacity.

As for videos, the PSAP practitioner’s use of deepfake recognition tools must become more agile and directly connected to their PSAP dispatching software suite. While there have been advances in the techniques and training used to recognise potential Swatting calls by sounds and deepfakes by the human eye, the steps, reminders, and, most importantly, time involved are limited for a PSAP dispatcher. Seconds count, and ‘yellow’ and ‘red’ flagging tools must be integrated into workflows.

Researchers are also considering several open questions: Will there need to be a balance between the public’s ease of access to a PSAP and the potential for harm? Are there data privacy issues here? Can texts and video chats be limited to IP addresses in the same physical jurisdiction as where the threat is supposedly happening? Will VPN calls to 911 or 999 need to be prohibited or marked as unverified? Should multi-factor authentication be applied to calls for lifesaving?

A piecemeal approach for an overall solution is a prudent course of action. Adding digital fingerprints to both hardware and software may be part of a long-term solution. On the other hand, retraining for PSAP operators to be better trained to distinguish and correctly action on those red and yellow flags (systemically presented or intuitively generated) can be implemented now, to reduce the massive response to an unsuspecting and unaware site, the target of a Swatting call. Akin to computer viruses, this is an agile threat in our volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world, which requires even more agile and heuristic solutions, immediately.

Michael Prasad is a Certified Emergency Manager® and the executive director of the Center for Emergency Management Intelligence Research. He has held emergency management director-level positions in the United States and worked for and volunteered with the American Red Cross, serving in leadership positions on more than 25 disaster response operations, including Superstorm Sandy’s response and recovery work. He researches and writes professionally on emergency management policies and procedures from a pracademic perspective, advises non-governmental organizations on their continuity of operations planning, and provides emergency management intelligence analysis for the National Security Policy and Analysis Organization at American Public University. His first book, entitled Emergency Management Threats and Hazards: Water, is scheduled to be published by Taylor & Francis/CRC Press in September, 2024. He holds a Bachelor of Business Administration degree from Ohio University and a Master of Arts degree in emergency and disaster management from American Public University. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the official position of any of these organizations.