Introduction

Since the emergence of QAnon as a conspiracy theory in 2017, some self-proclaimed QAnon adherents have committed violent extremist acts. In particular, the participation of QAnon supporters in the 6 January storming of the US Capitol in 2021 exposed the potentially violent character of the conspiracy. Such evidence has led researchers in terrorism and violent extremism studies to investigate the complexities of the QAnon movement and its relationship with violence.

In studying the conspiracy’s diverse and composite facets, scholars have noted that QAnon’s religious dimensions might play a role in individuals’ radicalisation towards violence. Indeed, QAnon’s alleged religious dimensions, especially those connected to Christianity, strongly influenced the active violent participation of QAnon supporters in the storming of the US Capitol and the 2022 Freedom Convoy in Canada.

In this Insight, we present our analyses of QAnon’s religious dimensions and their influence over affiliates’ propensity to violence. Findings are drawn from 121 images collected from QAnon Telegram channels over 18 months in 2020-2022. The visuals were analysed through semiotics and hermeneutical approaches, exploring the theological themes underlying QAnon religious narratives and interpreting their symbolism. Our study argues that QAnon religious imagery can be categorised into a series of types, all influenced by Christian theological themes. The visuals reveal a close relationship with US radical Christian evangelicalism and Christian liberation theology movements. On this basis, we note that QAnon’s religious dimensions can play an important role in boosting radicalisation and mobilisation to violence.

QAnon Religious Imagery

We analysed 121 images collected from QAnon Telegram channels, detecting the presence of four main categories of religious imagery: (1) purely religious; (2) QAnon-focused; (3) political; and (4) pop cultural. One or more of these types were often co-present within a single image. Here, we present six images as illustrative examples. The full results of our study are explored in greater detail elsewhere. The first category of images identified conveys purely religious symbolism, strongly shaped by Christian theology. Three recurrent themes characterise the religious imagery: the emphasis on Jesus as a saviour and protector; the portrayal of an eschatological battle between good and evil; and anti-Semitic tropes.

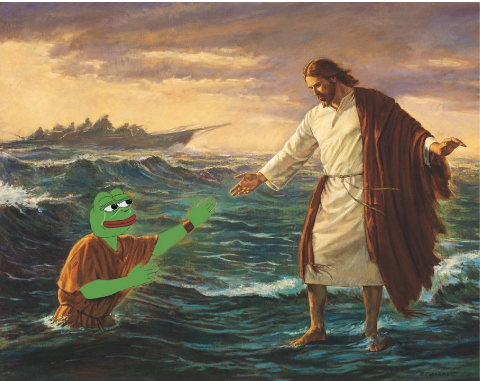

Fig. 1 is a prominent example of the theological emphasis on Jesus. The visual highlights the divine power of Jesus to save his believers, referring to one of the miracles performed by Jesus and narrated in the gospels:

Then Peter got down out of the boat, walked on the water and came toward Jesus. But when he saw the wind, he was afraid and, beginning to sink, cried out, ‘Lord, save me!’ Immediately Jesus reached out his hand and caught him. ‘You of little faith’, he said, ‘why did you doubt?’

Jesus, who walks on water, seems to metaphorically represent Q/QAnon, while the apostle Peter, portrayed in the image as Pepe the Frog, likely refers to a QAnon supporter. Paralleling the gospels’ account of the miracle, the image depicts a stormy sea. In the gospels, as Jesus saves Peter, the wind ceases, and the other apostles awaiting on the boat acknowledge and worship Jesus as the Son of God. Likely, the visual conveys the idea that the conspiracy has the power to save its believers in troubled times. The rescue of Pepe the Frog – a QAnon supporter – will lead other individuals to believe in the conspiracy and its supernatural power.

Fig. 1: Jesus walking on water and giving his hand to Pepe the Frog.

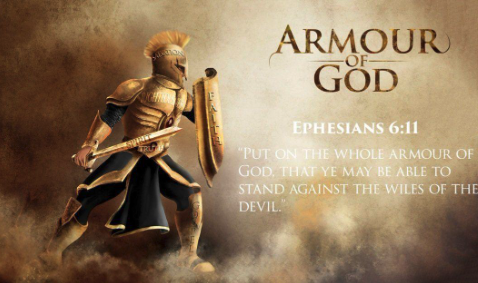

While numerous other images emphasise the figure of Jesus, other visuals convey broader Christian theological themes. In particular, images like Fig. 2 highlight the fight between good and evil by citing the sacred scriptures. The visual quotes Ephesians 6:11, a passage referring to the theological concept of spiritual warfare. Spiritual warfare entails individuals’ engagement in a fight against evil through adopting and practising Christian values. Hypothetically, the image encourages QAnon followers to stand by their values and conspiratorial truth and engage the evil in a spiritual battle. While the image’s meaning seems metaphorical, the overall narrative strongly adopts the language of warfare.

Fig. 2. Image quoting Ephesians 6:11.

The contrast between good and evil conveys additional meanings. Indeed, as Fig. 3 shows, the representation of Satan also implicitly spreads anti-Semitic tropes. The arms of Baphomet, popularly interpreted as the representation of evil, report two evident marks highlighted in red by QAnon followers: the words ‘solve’ and ‘coagula.’ The Latin words, which translate to ‘dissolve’ and ‘coagulate’ respectively, are references to QAnon beliefs concerning Satanic blood drinking. Indeed, the conspiracy affirms that the world is run by a Satanic cabal kidnapping children and harvesting their blood. QAnon claims can be seen as a variation of the long-established anti-Semitic blood-libel conspiracy theory, which accuses Jews of kidnapping and murdering Christian children to extract their blood and bake bread for Passover.

Fig. 3. Baphomet as drawn by Eliphas Lévi with the words ‘Solve’ and ‘Coagula’ highlighted in red by QAnon affiliates.

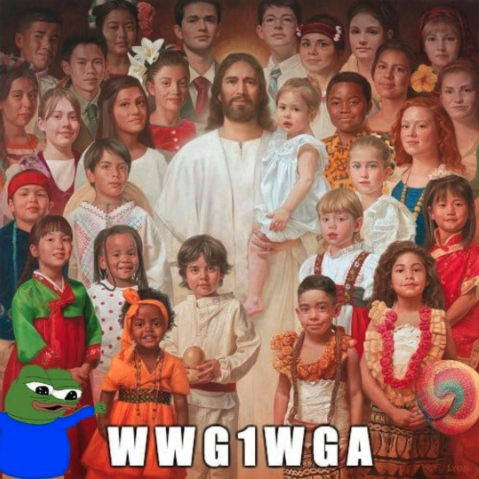

The second category of visuals collected is characterised by explicit QAnon symbolism infused with religious significance. As Fig. 4 shows, typical QAnon slogans such as WWG1WGA (‘When We Go One, We Go All’) are present in the imagery and mixed with both religious (Jesus) and pop cultural (Pepe the Frog) symbolism. The children depicted in the image provide an additional reference to QAnon narratives. Indeed, as previously noted, the conspiracy emphasises the need to protect children from a supposed Satanic cabal which sacrifices them in ritual murders.

Fig. 4. Image depicting Jesus Christ among children and Pepe the Frog and reporting the acronym WWG1WG.

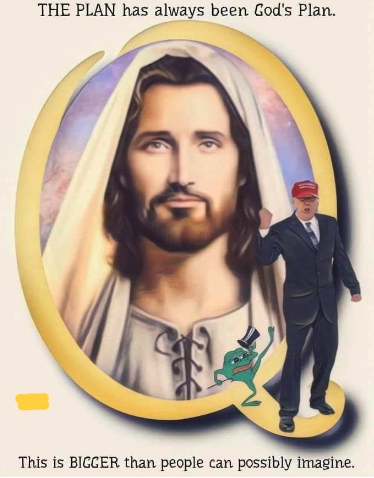

The third category of images merges religious themes with political narratives, mainly connected to US domestic politics. An illustrative example is Fig. 5, which mixes Christian theological themes, QAnon symbolism, and Trumpism. QAnon symbolism is conveyed through the letter ‘Q’ circling Jesus, which likely refers to the mysterious figure of Q, the author(s) of the Q-drops. In addition, the words ‘THE PLAN’ possibly refer to the notorious QAnon slogan ‘Trust the Plan’. In the image, however, ‘THE PLAN’ assumes simultaneously a religious and political significance. Indeed, the plan is ‘God’s Plan’ but simultaneously Trump’s plan as the former President. The overall meaning is that Trump’s political agenda encapsulates God’s plan.

Fig. 5: Image employing religious, QAnon, political and pop culture symbolism.

The fourth and last category of visuals heavily draws upon pop cultural symbolism. Pepe the Frog is among the most used pop cultural symbols (Figs. 1, 4, 5 & 6). Nonetheless, our study also notes the use of other pop cultural references like the white rabbit, deriving from both the Alice in Wonderland novel and the Matrix movies. The Pepe the Frog meme is also a tool for the QAnon community to connect to broader socio-political digital environments, as the meme has indeed been appropriated by the far-right.

QAnon as a Pseudo-Christian Extremist Movement

Our study expands on the argument that QAnon religious extremism is intertwined with US radical Christian evangelicalism. However, we make the case for paralleling QAnon pseudo-Christian extremism with liberation theology movements rather than with general US radical Christian evangelicalism to better account for QAnon supporters’ religiously inspired political violence.

This comparison acknowledges that QAnon and liberation theology movements differ ideologically. Indeed, far-leftist views have historically influenced liberation theology movements, while QAnon is usually associated with the far-right. Furthermore, liberation theology movements have not shared QAnon’s blatant anti-Semitism. However, despite these differences, QAnon shares key commonalities with liberation theology. Highlighting these similarities can help explore the influence of QAnon pseudo-Christian extremism on individuals’ radicalisation pathways.

The term ‘liberation theology’ encompasses a range of Christian-inspired social movements from Latin America, Africa, among US Black communities, Palestine, to East Asia that have developed since the 1960s. At the core of liberation theology is the dichotomy of oppressors vs oppressed, the emphasis on Jesus as a saviour and protector, and the theological need to take socio-political action to free the oppressed from socio-political injustice. This action-oriented ideological framework stems from the writings of key thinkers, including Paulo Freire, a prominent Brazilian philosopher, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian Dominican priest and Catholic theologian.

Freire’s work and his reflections on the systemic injustice and oppression characterising society deeply impacted Latin American Christian theologians. His calls to achieve a revolution “with neither verbalism nor activism, but rather with praxis, that is, with reflection and action directed at the structures to be transformed” triggered deep theological and socio-political reflections in Gutiérrez.

By reflecting upon the figure and message of Jesus, Gutiérrez merged theology and socio-political action, affirming that a “direct, immediate relationship between faith and political action encourages one to seek from faith norms and criteria for particular political options”. In his views, Jesus’ life conveys a model of praxis that leads to liberation through socio-political direct action against elites. Within this framework, the sacred scriptures serve as a tool for interpreting the reality of injustice and vice versa. The promise of salvation in them points to the primary role of Jesus as the saviour of the oppressed. However, Christ is not simply a spiritual protector and the way to remit from sins. Indeed, he also is a socio-political leader who guides believers in a fight for social justice and equality.

QAnon pseudo-Christian extremism shares key features with liberation theology’s religious-political framework. In a similar vein to liberation theology, QAnon emphasises the love of Jesus for the oppressed (QAnon followers), promises salvation and liberation from the perceived current political turmoil, and exhorts affiliates to engage in direct socio-political action. Furthermore, similarly to liberation theology, the conspiracy emphasises the importance of the sacred scriptures in interpreting current events, especially the oppression characterising society.

On top of this, QAnon’s attempt to merge theology and socio-political action manifests the concept of praxis outlined by Freire and, especially, Gutiérrez. Indeed, the visuals convey the idea that the theological-political message of Jesus ultimately resonates through the political agenda of the former US President Trump. The political agenda of Trump, viewed as a socio-political messiah ordained by Jesus, exhorts individuals to reflect on the unjust society they live in and act to liberate it from supposedly evil forces.

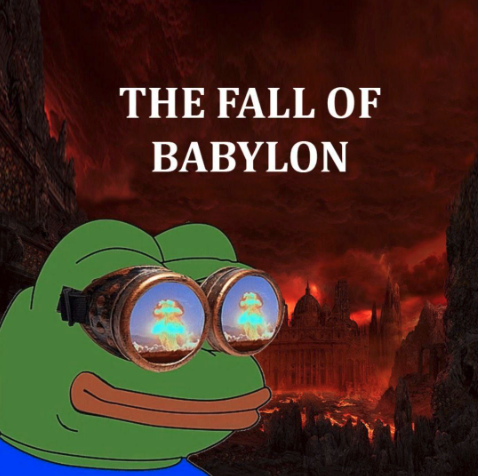

Fig. 6 is a prominent example and the ultimate symbol of the religious-inspired violent socio-political struggle QAnon affiliates engage in. The image depicts the US Capitol as Babylon, the ancient city that, according to the Bible, was conquered in the 6th century BCE by King Cyrus, whom God chose to allow the return of the exiled Jews to Jerusalem. Hypothetically, the visual conveys an implicit reference to former US President Trump. Indeed, Christian groups supportive of Trump have paralleled him and Cyrus, looking at Trump as a modern-day liberator. Through these lenses, the storming of the US Capitol, likely referred to in the image, becomes an event of religious and socio-political significance. It is a prophetic religious-political promise of liberation from the oppressors and salvation of the oppressed.

Fig. 6: Pepe the Frog and the US Capitol depicted as Babylon, a reference to nuclear war.

Conclusions

QAnon’s religious imagery is predominantly influenced by Christian theological themes infused with a wider set of narratives, including QAnon concepts, US politics and Trumpism, New Age, and meme-culture. The merger of these narratives creates a form of pseudo-Christian extremism focused on personal and socio-political liberation from perceived evil and oppression. By comparing QAnon with liberation theology, it is possible to better understand the movement’s strong connections with political extremism and aggression.

Our study highlights how the digital weaponisation of Christian themes by violent extremists represents a concerning yet underreported threat. Social media platforms and tech companies should evaluate such dangers, for instance, by acknowledging how religious symbols commonly associated with positive themes can be misused to harden barriers against perceived out-groups or to incite violence. To adopt an approach that is mindful of freedom of expression and, especially, freedom of religion, there is a need to conduct a threat assessment concerning content moderation policies. Any such evaluation should involve numerous stakeholders, including experts from the field of religious studies and representatives of religious communities.

Nicolò Miotto works as a Project Assistant at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), where he supports implementing projects on the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their means of delivery. Prior to joining the OSCE, he was a visiting scholar at Macquarie University, where he researched terrorism and violent extremism. His research interests include terrorism and violent extremism, arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation, and new and emerging technologies.

Dr. Julian Droogan is an Associate Professor at the Department of Security Studies and Criminology, Macquarie University (Australia) and the Editor of The Journal of Policing, Intelligence, and Counter Terrorism.