Introduction

Research continues to study how terrorist organisations exploit, or could potentially exploit, artificial intelligence (AI) for recruitment, propagandising, online account preservation, communication, and attack-planning purposes. In his study, Miron Lakomy found that while “chatbots had little use in facilitating access to terrorist content online,” they provided “sophisticated information” that could be useful for creating explosives and offered limited capabilities to those wishing to produce visual propaganda. A 2023 Tech Against Terrorism report documented a “pro-IS tech support group” sharing a guide informing users how to protect their privacy when using AI content generators and pro-IS supporters using AI to transcribe speech-to-text messages from IS leadership. The report also noted pro-Al Qaeda and Hamas accounts disseminating visual propaganda created or enhanced by AI. Daniel Siegel and Mary B. Doty noted how extremists could use generative AI to enhance visual/audio creativity through “customisable content that is both visually appealing and persuasive.”

As demonstrated by the aforementioned studies, the exploitation potential of AI by extremist actors is vast and diverse. To provide a deeper understanding of this pertinent subject, this Insight specifically focuses on the visual propaganda aspect by exploring a preliminary data set of 286 pieces of AI-generated/enhanced propaganda created or shared by pro-IS accounts across the following platforms: Instagram, Meta, Pinterest, and Pixiv. The first section provides an overview of the data, the qualitative analysis coding process, and the meaning of each qualitative code. The following discussion section examines relationships between the various codes and the wider implications that can be drawn from the data. The conclusion summarises the findings, reviews study limitations, and proposes points that those in the tech sector might consider.

Data and Methodology

Data Collection

To find AI images created by IS supporters, I first identified public pro-IS Instagram accounts through keyword searches and noted profile photos and posts that included AI-generated visual content. As I continued the exploration process, I noticed similar images that appeared repeatedly on multiple user profiles and timelines: cartoons of masked IS fighters with a blurred IS flag in the background. To find the source of this propaganda, I scrolled through various IS accounts’ ‘following’ lists. The person behind the account, who will be referred to pseudonymously as ‘IslamicState_Supporter’, posted a wide variety of content on Instagram and the account bio listed links to mirror or back-up accounts on Instagram and other platforms.

Public comments by pro-IS supporters asking about the AI content and IslamicState_Supporter’s responses confirmed that this individual was a) the original creator and b) had indeed incorporated AI into the propaganda creation process. Although a large part of the data originates from IslamicState_Supporter, I also screenshotted posts from other pro-IS accounts featuring AI images. The following includes the breakdown of the accounts and data:

*Pseudonyms are used for all listed account usernames

IslamicState_Supporter (overall total): 215

Description: This account’s cross-platform posting history consisted of original content incorporating the usage of AI.

- Instagram: 31

- Pinterest: 105

- Pixiv: 25

- Meta: 54

CampFundraising_Account: 28 pieces of data

Description: This account’s posting history focused on sharing news updates from the camps in Eastern Syria, promoting fundraisers allegedly organised by camp residents, and occasionally featuring AI-generated content. The AI content was not original or explicitly pro-IS.

IslamicState_Art: 19 pieces of data

Description: This Instagram account’s posting history included a variety of original content that appeared to be a mixture of hand-drawn artwork and images further enhanced by AI. Although many posts appeared to be exclusively hand-drawn images, this data set only included those that used AI capabilities.

Tawhid_Account: 9 pieces of data

Description: This Instagram account’s posting history featured AI-generated content and preferred incorporating a ‘traditional painting’ aesthetic for the images. It might be original content, and only one image was explicitly pro-IS.

Miscellaneous Accounts: 14 pieces of data

Description: Content from these Instagram and Pinterest accounts was gathered from various random pro-IS accounts that did not regularly feature AI-generated content.

Total number of collected images: 286

Coding Methodology and Codes

After saving the data, I reviewed each image and narrowed it to an overarching list of codes per the qualitative coding process outlined by Kurt Braddock:

- Identified a “general feel” for the content

- Generated an initial list of codes

- Consolidated similar codes into one larger code

- Organised any remaining codes while making sure that “all codes within each theme are conceptually similar” and “all themes have identifiable differences”

- Quantified the codes

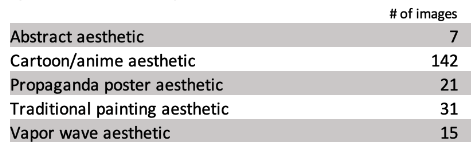

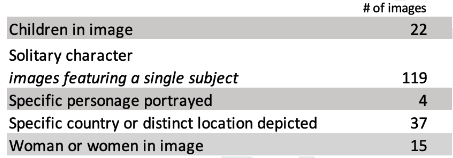

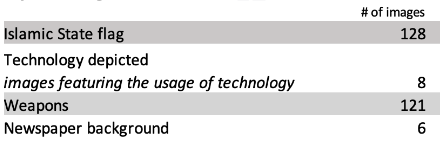

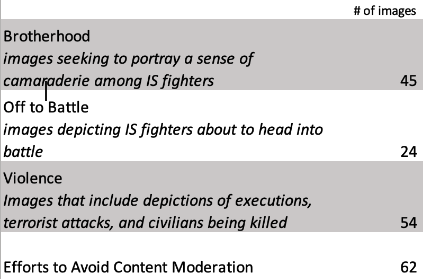

The codes for this data set include the following:

Style: Notes the artistic style of the content

People and places

Objects in Image

Other Themes

Preliminary Discussion

Content created by IslamicState_Supporter is overrepresented in the dataset, which impacts the coding outcomes. However, the fact that this individual has a vast amount of content compared to other pro-IS accounts provides an interesting case study of how AI capabilities can facilitate the mass generation of AI-enhanced extremist propaganda. As demonstrated by IslamicState_Supporter, the user can control the outcome creatively, particularly when combining AI capabilities with hand-drawn art and photo editing software programs. For further context, it is important to mention that IslamicState_Supporter directly stated their intention to create a diverse array of unique content, allowing us to understand the purpose behind the AI-centred propaganda initiative clearly.

When considering the full data set, the various codes help compartmentalise and identify elements in these AI-generated images, offering opportunities to consider pro-IS supporters’ creative and/or decision-making processes when making or reposting content.

Style

The cartoon/anime aesthetic was the most preferred image style, followed by content designed to appear as if it was created by traditional painting methods. Notably, the least popular category was ‘abstract aesthetic’ (Fig. 1), demonstrating gravitation toward realistic content. The emphasis on more realistic depictions may reflect supporters’ efforts to concretely solidify images of IS as a current reality through visual representation as opposed to abstract ‘artistic’ references to a so-called caliphate whose glory days have gone by.

Fig. 1: Example of the ‘abstract aesthetic’

People and places

The propaganda included images of various people and places to convey a variety of narratives. For example, IslamicState_Supporter often created or reposted images of a solitary IS mujahid engaged in different activities: holding an IS flag with a weapon at his side, standing or sitting alone right before carrying out a terrorist attack or engaging in an execution. Content featuring women tended to portray them as being in a silent moment of reflection, alone or with other women. Images of children primarily presented them as victims of war or young IS fighters participating in various violent activities, including beheadings. A handful of content depicted specific well-known individuals, including Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi and Abu Mohammad Al Adnani.

Although many commenters complimented posts in this category – especially ‘art’ that they identified as original – the AI-generated propaganda was not free from criticism. Some pro-IS supporters complained about the style being un-Islamic or haram; in response, the original posters stated their belief that it was not haram unless it included faces. Interestingly and perhaps in response to audience feedback, the recent majority of IslamicState_Supporter’s AI propaganda now only incorporates the IS flag. Only time will tell if negative criticism has led the propagandist to cease content depicting people.

Finally, images focused on identifiable locations or countries mostly sought to deliver hostile visual messaging to IS’s enemies: the United States, Europe (France and Italy), Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, China, and international coalitions. 8 of the 37 in this category showed AI renditions of Qubbat Al Sakhra (Dome of the Rock) with the underlying message that IS will march upon Al Aqsa and claim victory. In short, including specific geographies could portray either hostile messaging or hopes for victory to fellow supporters.

Objects in Image

Islamic State flags and weapons constituted the two most commonly-included objects in the AI-generated content. Although using an IS flag arguably increases the risk of receiving an account ban, the fact that it appeared in 45% of the posts shows the importance placed on promoting the ‘IS brand’ and quickly establishing the individual’s ideological affiliation to both in-group and out-group audiences. Of the 121 images featuring weapons, nearly 76% also used an IS flag, indicating propagandists’ efforts to link IS with shows of force, strength, and menacing threats to adversaries. AI does not reproduce IS flags, but this did not pose a hurdle. Although it is unclear what process the propagandists used to include IS flags, AI programs can create similar designs that would only need slight editing (Fig. 2), and in other instances, they make the exact replication of the flag when fed certain keywords (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 and 3: AI program’s approximate depiction of an IS flag and AI program’s exact depiction of an IS flag

A handful of images showed electronic devices (phones, laptops, etc.), added newspapers as the background ‘wallpaper’ behind the image’s main subject, or sought to imitate/promote the IS-linked news outlet, Amaq News Agency. Although media-centred items constituted a smaller proportion of the data, their visual presence speaks to the recognised importance that media and electronic devices play in propagandising, recruiting, and connecting fellow supporters with one another (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Partly AI-generated image of an IS supporter on a computer in front of a flag created by an IS supporter

Other Themes

As data collection continues, codes will evolve, but a preliminary coding revealed some other common themes, including brotherhood between IS fighters, depictions of men heading into battle, violence, and victimhood. Portrayals of executions composed 44%, and terrorist attacks comprised 33% of the data set, leading to a sum total of 77% of the content being designed to broadcast violence toward out-groups. Interestingly, images under the ‘off into battle’ category emphasised a sense of brotherhood and togetherness instead of focusing on IS fighters eliminating their enemies. Enemies were not even shown in these images, and the primary subjects were the IS ‘soldiers’ themselves.

Efforts to Avoid Content Moderation

Approximately 22% of the images used the content evasion strategy of blurring the IS flag in the background or overlaying a sticker. IslamicState_Supporter applied this method widely to images uploaded on their Instagram and Meta accounts but notably provided unaltered clear versions on Pinterest and Pivix.

Conclusion

The already-decentralised nature of pro-IS online communities fosters environments that encourage independent creativity, and, with the assistance of generative AI, supporters have an enhanced ability to create new visual content efficiently. In the context of this study, many pro-IS supporters valued creativity, as demonstrated in an instance where one original content creator posted a poll asking for input on which AI art styles people preferred and what they wanted to see next. The exchange created from the poll demonstrated the value of audience input and the creator’s effort to make fellow supporters feel a sense of agency in content outcomes.

Initially, content in the dataset could seem repetitive – such as images repeatedly featuring IS flags. In fact, IslamicState_Supporter received some critical comments suggesting the need for content diversification. However, a closer examination still captures deeper narrative nuances influenced by the overall colour scheme/style of the image itself, the decision on the part of content creators to include certain objects (such as a weapon, flag, or book), and the specific activity of the primary subject featured in the images.

As previously mentioned, IslamicState_Supporter’s content skewed the breakdown of the preliminary thematic patterns, which is a limitation in a certain way. However, expanding the data set beyond this one account and reviewing initial findings is still helpful for several reasons. First, including other accounts and posts demonstrates the emerging diversity of content and narratives that IS supporters seek to share through generative AI-based images. Secondly, this is an ongoing data collection process, and as it expands to include other sources, the diversity will provide a more accurate overview of the types of content being produced. Finally, it highlights how much content a dedicated pro-IS supporter can produce with AI tools. That being said, the top three code categories (‘Islamic State flag’, ‘Weapons’, and ‘Solitary character’) reflect the mindsets of the unofficial propagandists included in this data set, and they heavily placed an emphasis on conveying bolder imagery.

In terms of some ideas for future research avenues, research concerning pro-IS visual propaganda created or enhanced by AI could cross-compare identified narratives with those found in official propaganda, note gendered messaging conveyed through imagery and aesthetics, or compare how the overall objective of an account influences how it designs AI-based visual content. It would also be interesting to compare the narratives produced in supporter-created ‘art’ with studies, such as Charlie Winter’s work, that have documented themes conveyed in official visual IS propaganda.

The following points may be helpful to those in the tech sector looking to counter the production and dissemination of AI-generated terrorist content:

- Relying solely on AI programs to produce extremist images may be limiting. However, AI combined with original art and photo editing apps produces a much wider array of creative possibilities.

- Identifying word combinations that most effectively enable the creation of AI-generated images for extremist purposes would aid in restricting its creation at the source.

- Generative AI could increase the weight extremist groups place on disseminating their content to the public because it would act as an original reference for AI to recreate similar images.

- Gaps in content moderation efforts may lead IS supporters who create AI-based propaganda to gravitate towards certain platforms and build a repository for these images while applying counter-content moderation strategies to partially blurred or covered versions they share on sites like Instagram or Meta (as demonstrated by the IslamicState_Supporter case).

- Individuals who create extremist content with the aid of generative AI undergo a trial and error process, which includes experimenting with keyword strings that tend to create the desired images successfully. Even if content moderation efforts detect words such as ‘Islamic State’, there are easy ways to work around this with alternative phrases. Identifying these alternative word combinations that result in the generation of explicitly extremist visuals is important.

- The harm done by AI reproductions of racist images on a general level is of concern first and foremost, but in addition, it is necessary to consider how bias tendencies aid extremists in their efforts to create visual and text-based propaganda, whether white supremacists or pro-IS for example.