Introduction

The advent of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technology has introduced a myriad of user-friendly tools and tactics such as image generation tools and deepfake audio generators for various malicious actors to generate sophisticated propaganda and disinformation narratives. In the past, online Islamic extremist networks have evolved and adapted their recruitment and radicalisation strategies. In the wake of the AI revolution, many fundamentalist subcultures have become increasingly digitally savvy, utilising memes and co-opting online trolling in their propaganda efforts.

This Insight explores one particularly alarming development: the use of AI by a coordinated, unattributed inauthentic influence network which uses fake accounts to spread a strategic narrative promoting the millenarian belief that the Islamic apocalypse is imminent. Hundreds of inauthentic accounts have posted and reposted hundreds of TikTok, Youtube, and Twitter videos that suggest that a man named Muhammad Qasim is directly communicating with Prophet Muhammad and God through his prophetic dreams. The videos not only promote Qasim but suggest that anyone who does not accept him should expect the “deepest depth of hellfire”.

Rooted in religious contexts, Islamic millenarianism predicts a future societal transformation precipitated by a cataclysmic event. This event is believed to signal the end of the existing world and the beginning of a new one. This new world is conceived as a ‘superior’ one because of its absence of ‘shirk’ — the sin of idolatry. Jihadists often interpret this as, for example, listening to non-Islamic music, associating with any non-Islamic group, and following anything other than Sharia law. This network reflects Islamic millenarianism, an ideology that represents an extremist conspiratorial worldview that purports the return of the messianic figure known as the Mahdi (the Guided One) – the final leader in Islamic eschatology. The flurry of social media accounts utilise image generation tools and audio deepfakes to spread sentiment supportive of Pakistan’s role in the Muslim world and disinformation regarding the arrival of Imam Mahdi, signifying the impending apocalypse on TikTok, YouTube, and Twitter. This disturbing development represents the adoption of emergent technologies by extremist elements that social media platforms must be prepared for.

Muhammad Qasim Dreams

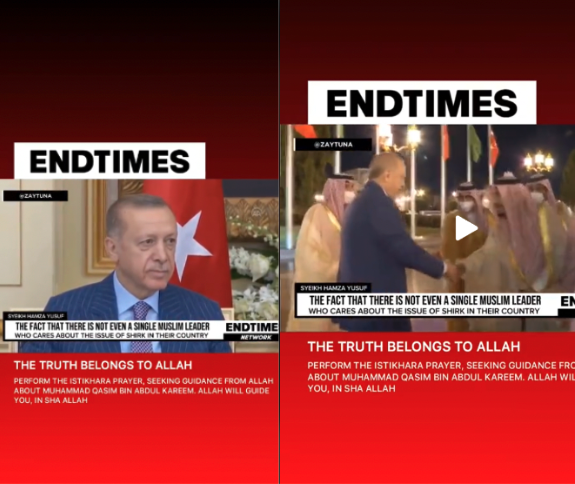

Muhammad Qasim is a 45-year-old man from Lahore who claims to be receiving divine dreams from Allah and Prophet Muhammad. Qasim’s descriptions of his dreams in these viral videos identify him as the sole legitimate Islamic leader while denouncing predominantly Muslim nations such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey as ‘apostates’ who have abandoned true Islam (Fig. 1). His objective goes beyond spreading millenarian beliefs; it aims to destabilise established Islamic authorities and nations. Pakistan is assigned a messianic role in achieving a ‘pure world’ devoid of shirk. His emphasis on ‘purity’ creates a stark division of ‘us versus them’, categorising people as ‘true believers’ or ‘idolaters.’ This separation fuels discrimination and potentially incites violence against those that deny Qasim’s legitimacy.

Fig. 1: Content destabilising perceptions of Turkey and Saudi Arabia

Qasim’s videos are available in several languages, including English, Urdu, Bangla, Arabic, Indonesian, and Malay, indicating that his target audience spans South and Southeast Asia, as well as English speakers. The objectives and motivations of the content creators remain somewhat elusive, other than their unequivocal support for Qasim as the prophesied Mahdi and their portrayal of Pakistan and its military as divinely ordained to initiate the apocalypse. The network seeks to elevate Pakistan’s theological significance. Moreover, it may also be an effort to enhance Qasim’s stature and rally support from fundamentalist Muslims worldwide.

AI-Generated Content: Amplifying Propaganda

The inauthentic network boosting Qasim includes rapid sequences of AI-generated images and audio deep fakes, sometimes overlaid with one another. Based on the style of the images – unrealistic faces, too many fingers, inaccurate lettering etc – these images appear to be developed through generative AI technology and serve to validate Muhammad Qasim as Imam Mahdi (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Examples of AI-generated images used by the network

Numerous inauthentic or fake accounts have been created across TikTok, YouTube, and Twitter solely for the purpose of boosting short-form, AI-generated propaganda videos disseminating disinformation surrounding Qasim’s identity as the Mahdi. Although it remains challenging to quantify the extent of this content’s impact on shifting people’s beliefs and opinions, we can assert that this network has commanded substantial attention on social media.

This network has built a following among Islamic communities across TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Despite some takedowns on TikTok for Terms of Service violations, the network continues to thrive; the network’s three most commonly used hashtags have over 540 million views on TikTok, with the #muhammadqasimdreams hashtag garnering over 68 million views. On Twitter, Furthermore, many bot accounts coordinate to spread inauthentic content utilising the hashtags #MuhammadQasimDreams, #MimpiMuhammadQasim, #Ibelievemuhammadqasim, #MuhammadQasimImamMahdi and #avoidshirk. Further evidence of cross-platform influence is the Muhammad Qasim PK YouTube channel, with ~319k subscribers. Across all platforms, the network utilises overlapping video content, consistent messaging, common AI-generated graphics and deep fake audio material.

This analysis of AI-generated content unveils the proficiency of this Islamic millenarian network in employing sophisticated techniques to disseminate its extremist narrative to fuel conspiracies about the Mahdi, retain global viewers’ attention, and rapidly produce content.

The Use of AI-generated Images to Amplify Muhammad Qasim

Fig. 3: The use of AI to legitimise Muhammad Qasim in TikTok and Youtube videos

In the videos circulated by the network, it is apparent that AI-generated images are used to glorify Qasim, depicting him in heroic postures, interacting with prophets, or being involved in spiritually significant events (Fig. 3). Even if an image appears artificial or exaggerated, it may still evoke emotional engagement, which can motivate users to share the content within their networks, increasing its virality. AI-assisted image generation enables malicious actors to circumvent traditional labour-intensive image creation methods such as Photoshop in order to produce impactful content more efficiently.

Jihadist propagandists have traditionally relied on pre-existing footage from movies or games or film their own content, often with limited resources. However, generative AI has enabled the instant creation of customised, thematic images. These images depict scenes of unity, the purity and wisdom of a millenarian leader, judgement day, battlefields, and even portrayals of catastrophic events suggestive of the apocalypse. By portraying Qasim as a heroic figure, the content creators leave a lasting impression of his greatness, reinforcing the belief in both the impending apocalypse and his authority as the Mahdi. With AI, these content creators can distribute visually appealing, emotionally engaging, and ideologically aligned content swiftly, amplifying the influence and reach of propaganda campaigns.

Leveraging Audio Deep Fakes

Audio deep fakes, or artificial recreations of human voices, are also utilised by the pro-Qasim network to amplify the narrative that Muhammad Qasim is the Imam Madhi. Some videos feature prominent Islamic scholars including Zimbabwe’s Imam Mufti Menk, Indian Televangelist Zakir Naik, and Americans like Imam Nouman Ali Khan and Yasir Qadhi. More recently, the group created an audio deepfake of former American President, Barack Obama endorsing Qasim as the Imam Mahdi. These videos overlay AI-generated voices in the background to accept the prophetic dreams of Qasim and his rise as the first sign of Judgment Day.

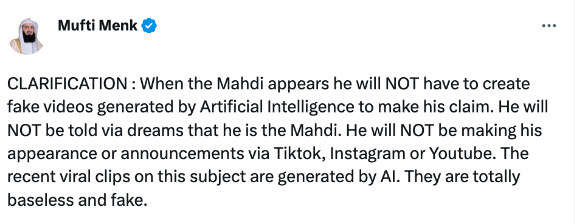

The quality of these early audio deep fakes is poor. This is most evident in an AI-generated audio clip of Mufti Menk purportedly endorsing Qasim as the “redeemer of Islam” (Fig. 4). Despite their subpar quality, these deep fakes have captured the attention of some of the key figures they’ve exploited, consequently propelling their virality. For instance, the prominent Islamic scholar Mufti has tweeted and posted on Instagram denying that he has declared Qasim as Imam Mahdi, calling out the videos as fake (Fig. 5). Yet, by doing so, he inadvertently amplified the network’s narrative. After gaining the scholar’s attention, dozens of videos were posted on Youtube and TikTok refuting Mufti’s claims about Qasim. This demonstrates how a successful deception does not require high-quality deep fake audio; even low-quality synthetic audio can create enough controversy to serve the network’s goal of amplification. A recent study has illuminated that humans are capable of distinguishing deep fake audio from real audio only 73% of the time. Even low-quality deep fakes without amplification from famous individuals can be a potent tool for groups aiming to use the voices of significant figures to spread chaos or further their agenda. In its latest videos, the network has demonstrated an advancement in its deployment of audio deepfakes. The network blends authentic audio from various Imams with synthetic voices within a single video (Fig.6). This masking technique obscures any inconsistencies in the fake audio, making it more challenging for listeners to distinguish between the real and the synthetic voices. This underscores the necessity for social media platforms to employ sophisticated detection techniques to safeguard the public from such deceptive tactics.

Fig. 4: Early Low-Quality Audio Deep Fakes of Imam Mufti Menk endorsing Muhammad Qasim as the ‘Imam Mahdi’

Fig. 5: Mufti Menk denouncing the AI-generated videos on Twitter

In its latest videos, the network has demonstrated an advancement in its deployment of audio deepfakes. The network blends authentic audio from various Imams with synthetic voices within a single video (Fig. 6). In another video, the network clipped a video of a CNBC interview between Musk and journalist David Faber and then blended synthetic audio with real conversations to make it seem that Muhammad Qasim and Imran Khan were the focus of the conversation (Fig. 7). These advanced masking techniques obscure any inconsistencies in the fake audio, making it more challenging for listeners to distinguish between the real and the synthetic voices. This underscores the necessity for social media platforms to employ sophisticated detection techniques to safeguard the public from such deceptive tactics.

Fig. 6: Genuine and Synthetic Audio Mixing of Prominent Imams to Endorse Qasim

Fig.7: Clipped video of an interview with Elon Musk

Moderation Challenges

Detecting AI-generated content has emerged as a key area of concern for social media companies amid the surge of synthetic content online. Companies like Google, Microsoft, OpenAI and others have pledged to focus efforts on digital provenance techniques such as watermarking to aid synthetic content detection. However, the effectiveness of such methods is questionable – the efficacy of watermarking is easily diminished when the content can be altered, compressed, cropped, or tampered with. This challenge is compounded when AI-generated content proliferates across multiple platforms, bypassing removal attempts, and building followings in various Muslim communities.

The images used by the network discussed in this Insight were clearly AI-generated and aid its agenda by employing a cost-effective approach to disseminate propaganda that elicits emotional reactions and generates likes, comments, and shares. There are many entities developing AI-generated technology that have not committed to watermarking their content, possibly due to limited resources, a lack of interest, or a perceived lack of regulatory consequences for not doing so. As a result, detecting AI-generated content at scale is a labyrinthian process which requires collaboration between a variety of stakeholders to secure digital provenance.

To address this issue, platforms need to collaborate with industry working groups and civil society organisations through robust knowledge sharing. By hashing or adding harmful content to shared platform databases, they can prevent replication and better address the spread of extremist networks like Qasim’s. As more inauthentic networks turn to generative AI, it will be necessary for social media companies to hash harmful AI-generated extremist content.

Content moderation becomes complex when the content contains specific religious and cultural nuances requiring subject matter expertise to decipher what is violative and what is reflective of the faith. In the case of Qasim’s network, spreading false information about being the Mahdi using fake accounts is violative, while content about the Mahdi as a concept is not. Despite these challenges, platforms must share indicators of concern between their threat intelligence and moderation teams to stay vigilant about the evolution of AI-generated content used in extremist communities like Qassim’s self-glorifying millenarian network.

Conclusion

The role of AI technologies in extremist propaganda represents the new frontier in the fight against influence campaigns and the rapidly evolving tactics of malicious actors. The campaign’s ability to exalt Muhammad Qasim as the Mahdi is not the only criterion to measure its success – the network’s adept use of AI-generated content, its ability to inspire fundamentalist Muslim audiences, and gain a significant amount of online attention must be considered. The Qasim network exemplifies the urgent need for improved detection and moderation strategies, enhanced digital literacy, and robust accountability strategies for technology companies to combat the proliferation of harmful AI-generated content at scale.

Daniel Siegel is a Master’s student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. With a foundation as a counterterrorism researcher at UNC Chapel Hill’s esteemed Program on Digital Propaganda, Daniel honed his expertise in analyzing visual extremist content. His research delves deep into the strategies of both extremist non-state and state actors, exploring their exploitation of cyberspace and emerging technologies. Twitter: @The_Siegster.

Bilva Chandra is a Technology and Security Policy Fellow at the RAND Corporation. Prior to RAND, she led product safety efforts for DALL-E (image generation) at OpenAI, spearheading work on emerging threats and extremism, and led disinformation/influence operations and election integrity work at LinkedIn. Bilva is a Master’s graduate of Georgetown Security Studies Program (SSP) and Bachelor’s graduate of the Georgetown School of Foreign Service. Bilva has been published in the Modern War Institute and The Strategy Bridge on AI topics and has participated in several panels and podcasts on extremism, disinformation, cyber, AI safety, and Responsible AI.