Introduction

The use of online memes is a cultural stamp of the alt-right community; the packaging of political ideology into humorous or ironic media shared within a collective as a set of inside jokes and references is a key tool in the radicalisation process. Drawing on existing research, this Insight identifies three central ways that memes contribute to alt-right culture. First, the use of humour in the form of memes as a collection of ‘inside jokes’, particularly at the expense of an externalised group, intensifies an ‘us vs them’ narrative which promotes social othering. Second, the ‘memeification’ of real-life violence also facilitates a process of desensitisation by presenting extreme content as ironic or light-hearted, making it more consumable and allowing the radicalisation process to occur in a more subtle manner. Third, the ironic edge of meme culture is intentionally useful in its ability to mask serious ideological claims as ‘edgy’ jokes, eschewing any responsibility when external forces attempt to hold alt-right groups accountable for online abuse. In order to combat this specific form of hate and radicalisation, steps should be taken to recognise forms of violent extremism which act as ‘dog whistles’ – that language which is encoded or meaningful only to members of the alt-right, and thus act to incite violence within ‘in-groups’ without provoking reaction from ‘out-groups’.

The Communal Value of Humour

In order to understand the use of memes in far-right radicalisation, one must understand the communal value of humour. Greene and Day’s commentary on the subject states that “through collective laughter, satire can help build a sense of community for those in on the joke”. In situations where a group shares humour, they are drawn closer as a collective. When members of a group believe themselves to be in on an exclusive joke, it “fosters greater social affiliation”, and promotes a tighter sense of community among them.

The alt-right benefits from this aspect of shared humour through meme culture. According to the NSPCC guide on factors which increase vulnerability to radicalisation, individuals who are isolated or feel rejected from mainstream society are most at risk. Individuals who are lonely and long for a sense of community or belonging are vulnerable to the alt-right’s attempts to provide relief from feelings of social rejection.

Humour at the Expense of the ‘Other’

The exclusionary nature of the communal space which is made through shared meme culture is intensified further by the fact that the jokes made by the in-group- are often at the expense of the out-group. Alt-right humour is often shrouded in memes which make light of violent events – even glorifying them in many cases. An effective example of the exclusionary effects of in-/out-group humour within incel communities is seen in the meme culture which emerged off the back of the 2014 Isla Vista shooting. The phrase ‘going ER’ (referring to the shooter, Elliot Rodger) emerged in alt-right communities as a ‘memeified’ term for committing acts of misogynistic violence, specifically ones similar to the 2014 massacre. Here, it is important to emphasise the comradery derived from sharing in-jokes as a group – specifically ones made up of references which seem vague or unnoticeable to outsiders. Communities form surrounding the killing as individuals threatening to ‘go ER’ or referring to Rodger as the ‘supreme gentleman’ (a term coined in Rodger’s manifesto) make subtle yet not overly violent nods to the attack that only those in the know would notice. As a result, this memeification of violence means that individuals are able to root their exclusionary humour in a sense of comradery – a collection of references, vague enough to only be understood by a certain few, turning acts of violence into pop culture references. This renders humour an efficient tool in radicalising individuals into a single tight community within the alt-right characterised by its opposition to the social others whom they mock.

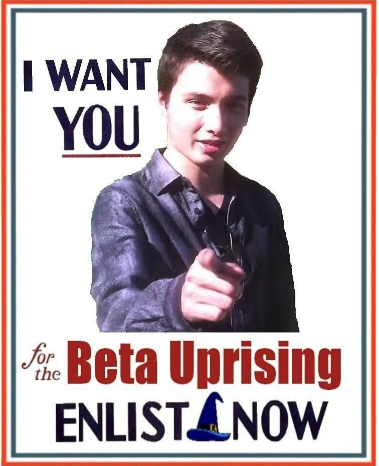

Fig. 1: An Elliot Rodgers meme, a parody of the war-time ‘I want you’ US army recruitment posters, replaced by an invitation to join the ‘Beta-uprising’.

A Tool for Desensitisation

As well as acting as a tool to intensify a communal ‘us vs them’ narrative amongst alt-right groups, memes can be used as an effective desensitisation tool. The gamification of the 2019 Christchurch shooting is one example of a violent event being popularised as a piece of alt-right culture, resulting in the desensitisation of violence towards minority groups.

In the 2019 Christchurch mosque attacks, the perpetrator, a far-right white supremacist, live-streamed his attack. The video was then gripped by the online alt-right community, and edited and recreated in various manners. Examples include a recreation of the shooting in a playable Roblox version, as well as an edited version of the livestream superimposed with a ‘kill count’ and ammo level, akin to a typical first-person shooter video game. Both of these recreations display a certain level of empathetic distance from the event itself, trivialising the atrocity and detracting from its gravity.

Fig. 2: A screenshot from the livestreamed attack with the Call of Duty title logo pasted over it, an example of gamification.

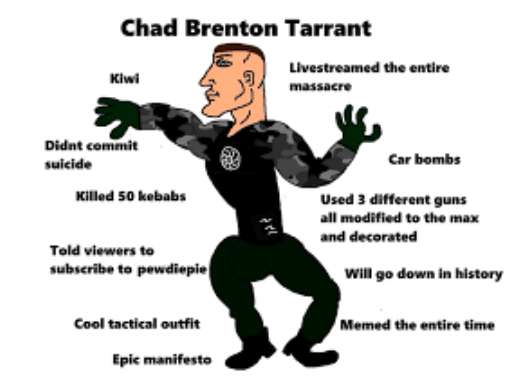

Fig. 3: A popular ‘Chad’ meme of Brenton Tarrant referencing other popular alt-right memes within it

This desensitisation through the memeification of violence towards minority groups is an important part of a radicalisation process; the sharing and understanding of meme culture is not only a marker of belonging for the alt-right community but also exists as a tool in and of itself to dehumanise and devalue minority groups. Linking back to the vulnerability of new members, the pressure to join the group ‘in-joke’ – no matter how egregious – is high enough that humour acts as an effective tool to push individuals to desensitise themselves to violence towards others for the sake of being part of a community. By taking content like the Christchurch video and making it part of an array of group in-jokes, the alt-right creates an environment in which users are desensitised to gore and violence, specifically against minority groups. In turn, this intensifies the dehumanisation of minority groups, further contributing to the hate and violence towards them from extremists.

Eschewing Responsibility

Adjacent to the use of memes online, humour more broadly can be employed as an effective form of damage control for the alt-right. In cases where alt-right ideology is scrutinised in the public eye as being offensive or damaging, responsibility is evaded if the content is claimed to be said in jest rather than sincerely. This can be explained by comparing the use of humour by the alt-right to Schrödinger’s Cat; a cat placed in a radioactive box is both dead and alive until the box has opened. In the same way, it could be argued that statements made by the alt-right are simultaneously meant jokingly and sincerely depending on the intended audience.

In November 2016, Richard Spencer, an American neo-nazi and white supremacist, ended a conference with the words “Heil Trump, heil our people and heil victory”, which was met with a Nazi salute by the crowd. Spencer, when questioned about the reaction from his followers, declared that the Nazi salutes were “clearly done in a spirit of irony and exuberance”. The salutes, then, until criticised, sit in a purgatory between sincerity and jest. In a similar way, in a recent BBC interview (removed the day after its publishing), Andrew Tate claimed that his comments about women’s bodies belonging to men were a joke, and should be contextualised as such. However, Tate’s reticence to disassociate himself from those who embrace and promote his misogynistic rhetoric implies that he only presents his ideologies as ironic when faced with opposition.

Hateful ideological statements or actions often exist within a grey area in far-right discourse, categorised as satirical or authentic dependent on the audience. This duality allows notions to exist simultaneously as ironic and sincere, oscillating between the two depending on the context in which they are discussed and inhabiting the space of both ‘edgy humour’ and tangible claims. For instance, when new members of a far-right group are exposed to a Nazi salute, the act loses much of its gravity when done ironically, compared to when it is carried out earnestly. Consequently, this ever-shifting cloak of irony becomes a powerful tool for desensitising individuals to the weight of hateful far-right actions and values.

Combatting the Issue – Hearing the Dog Whistle

The tendency for violent extremism to manifest through humour makes it difficult to monitor and combat; inside jokes become dog whistles, meaning that coded language is used to convey violent messages to an intended group in a way which is less detectable to outsiders. In order for tech companies to combat the issue of hate shrouded in humour, it is proposed that policies should place focus on the nuances of dog whistles on platforms. Moderation technologies which only target overtly violence-inciting content are insufficient when dealing with alt-right memes which often exist within the ‘legal but harmful’ category.

Figures 1 and 2 above are not overtly violent; an individual who did not know Elliot Roger, or had not seen the footage of the Christchurch shooting, could scroll past such memes without much thought. They exist with little meaning unless one understands the implications and references embedded in the imagery and language. In order to break down the dynamic between humour and authenticity within the alt-right, tech companies must push policies which recognise content which sits within a grey area of legality.

Conclusion

Humour in the form of memes serves as a powerful weapon for the alt-right, effectively facilitating radicalisation by ‘softening’ extremist ideologies through ironic engagement in exclusive ‘in-jokes’. These communities thrive on widening the social and empathetic distance between the in-group and the out-group – typically made up of minorities – who are consistently the butt of such ‘jokes’.

Individuals susceptible to radicalisation often pursue a sense of community or belonging they may lack in real life. Thus, the alt-right’s shared in-jokes contribute to an appealing sense of group identity. The memeification of the Christchurch shooting video, and the self-proclaimed irony of Andrew Tate and Richard Spencer’s hateful beliefs, demonstrate the alt-right tactic of disguising offensive content and ideas as jokes rather than sincere expressions, dampening their potency to those who would find them offensive or abusive. In doing this, Schrödinger’s Cat idea is reinforced, as alt-right ideology tends to exist in a state of both irony and sincerity until it is met by a recipient. If that recipient is within the alt-right in-group, the statement holds genuine meaning. If they are a critic, reducing the ideology to a joke makes it more challenging to hold them accountable for the spread of hatred.

While identifying and removing content which sits within the grey category of ‘legal but harmful’ is difficult, platforms which identify harmful content exclusively as that which is overtly violent fall short of encompassing the full scope of alt-right culture. There must be an understanding that alt-right violent content exists within its own selection of coded memes and references. As with any form of encoded language, the true meaning, and the harm it causes, is only challenged once policies are made to ‘hear’ such dog whistles.