Introduction

Founded in 2009, Artkos has since emerged as one of the leading English-language publishers of Eurasian, identitarian, and New Right books. Alongside reissuing tracts by classic figures of the far right, such as Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist, Arktos has published numerous books by an array of contemporary ideologues, including Alexander Dugin, Tom Sunić, and Jason Reza Jorjani. In 2012, the anti-fascist Searchlight magazine reported: “It will be interesting to see how the reputable mainstream printers Lightning Source [a unit of Ingram Content Group] feel about having such a dubious client as Arktos”. A close inspection of the back matter in Sanctuary Press’ books, a publishing house which primarily reprints material from the ideologues of the interwar British Union of Fascists, reveals that Arktos is not alone among the questionable users of Ingram’s services. Indeed, even Anders Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 Oslo attacks, specifically called for the use of such services, including Ingram’s Lightning Source, to distribute his manifesto.

In November 2021, almost a decade after Searchlight voiced its concerns, Ingram notified Arktos that it would terminate its services. Arktos relied on Ingram for the production and distribution of its books. After an unspecified mistake allowed Arktos to continue printing via Ingram throughout 2022, a termination notice was emailed to Arktos Chairman, Daniel Friberg, in February 2023.

This is not Arktos’ first experience with what it has belittled as “obtuse attempts at deplatforming”. One of the group’s Kickstarter campaigns had previously been closed and its Twitter account was suspended from 2021 until March 2023. Arktos’ deplatforming by Ingram was, however, the most serious challenge that the publishing house has confronted since its inception. Against this backdrop, this Insight interrogates the implications of Arktos’ deplatforming and its response thereto. It emphasises Arktos’ central role in propagating ostensibly highbrow New Right literature and highlights the comparatively neglected nexus between online print-on-demand providers and the dissemination of far-right and white supremacist material.

Free Speech and Putin’s Lackeys

Arktos has framed its deplatforming as part of a broader “War on Dissident Thought” and “one of the greatest attacks on free speech to date”. Artkos Chairman, Daniel Friberg, has cast Artkos in the role of David, while Ingram, “the world’s largest book distribution monopoly”, is characteristically depicted as Goliath.

Recourse to the supposed inviolability of free speech has been a common preserve of the far right. Arktos’ supporters have mimicked this narrative. The national socialist websites Nordfront and Frihetskamp condemned Arktos’ deplatforming, a position similarly espoused by sympathisers on Telegram and Twitter. Some users have reckoned with the inevitability of Arktos’ deplatforming and the need to create an independent far-right publishing ecology. For one supporter on Telegram, “Antelope Hill and Counter-Currents will end up cancelled from global distribution too. Everything will end up virtual only.” Paul Gottfried, editor-in-chief of the paleoconservative magazine Chronicles, likewise presented Arktos’ deplatforming as “an ominous sign of the disappearance of intellectual freedom in the West” under a supposed “woke tyranny”. Unlike other commentators, Gottfried also called attention to what he believes to be the hypocritical stance of Ingram. While stifling the New Right, Ingram continues to publish so-called “terrorist tracts” that support BLM’s “racist ideology”.

As an adjunct to announcing its deplatforming, Arktos promoted the March 8 launch of its new website (see Figure 1). Supporters responded with enthusiastic anticipation and expressed their loyalty to the publishing house. As one Telegram user added: “We either support publishers like Arktos, Antelope Hill, Counter Currents, etc. or they cease to exist.” On Twitter, numerous fellow travellers—including the aforementioned Russian Eurasianist Alexander Dugin and white nationalist Tom Sunić, alongside the far-right publishing house Antelope Hill and the Swedish traditionalist think tank Motpol—posted about or otherwise retweeted news of Arktos’ deplatforming. For instance, one user praised Arktos’ pioneering role in “dissident publishing” and implored their followers to “pls support them”. As another supporter posted, one ought to assist Arktos’ “amazing work” against a “gang of censorious harpies”.

Fig. 1: Arktos advertised the release of its website across various social media platforms

One voice stands starkly apart, namely Colin Liddell, a mainstay of the alt-right. In a post on NeoKrat, Liddell alleged that the timing of Ingram’s “highly unusual act of deplatforming” was no coincidence, but a product of pressure applied by “Western Deep State agencies’’ due to Arktos’ “pro-Kremlin ties”. Yet, given Arktos’ plight, this narrative has seemingly gained almost no traction; after Liddell shared the article, the only two likes on the post were from his own accounts.

Undermining Distribution

Arktos’ deplatforming carries serious distribution-related implications for the group. Arktos hosted the 2017 ‘Identitarian Ideas IX’ conference in Stockholm and participated in the meetings of the so-called London Forum. Such events provide crucial opportunities to sell books and interact with a transnational network of far-right agitators. Yet, in an inherently international market, the digital realm will be central. The loss of Ingram’s printers and attendant distribution network poses a potentially acute challenge for Arktos. In turn, Arktos has assured its readers that it is in the process of offering more books. As Friberg claimed: “We are currently undertaking a comprehensive overhaul of our operations to reinstate all titles for distribution as soon as possible”.

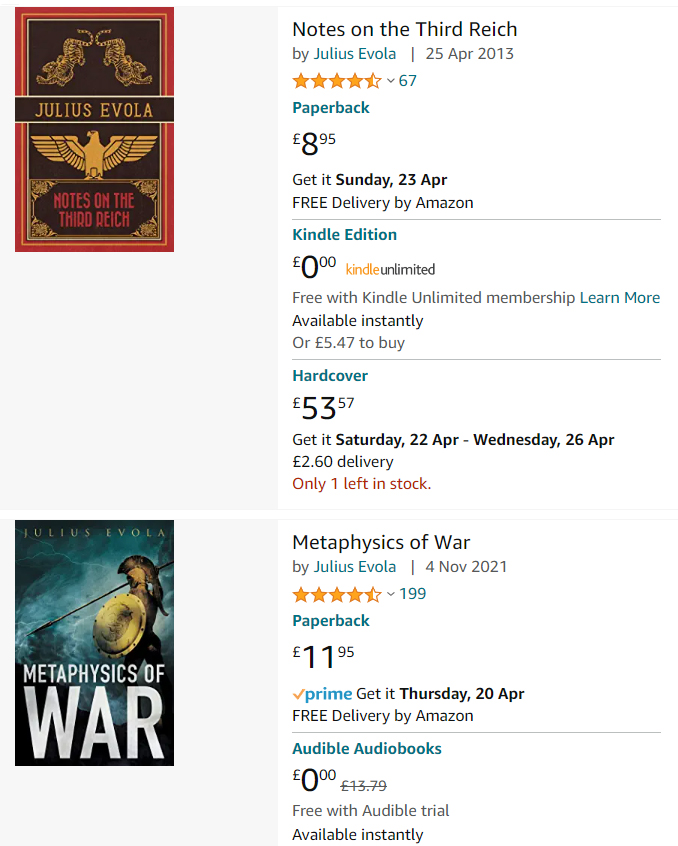

Arktos also applauds itself for serving as the foremost publisher of Alexander Dugin, Julius Evola, and the broader European New Right. Beyond the content of its books though, one of Arktos’ key assets has been its capacity to produce aesthetically impressive volumes. Arktos has sought to uphold what it calls the “highest quality in all senses, from outer aesthetics to inner content”. Excluding its audiobooks and eBooks, large swathes of its material had ceased to be accessible. While some texts could still be purchased on Amazon and the Swedish online book retailer, Adlibris, the available range on Arktos’ online store conspicuously declined, albeit a vast array of its paperbacks are steadily returning to the Arktos website (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2: A range of Arktos’ books that are available on Amazon as of April 2023

Subscribing to the Far Right

Arktos inaugurated a new website on March 8, one of noticeably professional quality. The group has adopted and displayed a pithy new tagline, “Making Anti-Globalism Global Since 2009”, capitalising on its prominent status and longevity as a publisher of New Right material (see Figure 3). Furthermore, Artkos’ new aesthetic is a far cry from the defunct altright.com and stands visually apart from its closest rival in style and content, the American-based Counter-Currents. Artkos’ recent overhaul may be fuelled by its deplatforming, but also compounded by internal schisms within the far right and an anxiety to avoid losing ground to Counter-Currents after a public breakdown of relations in 2019.

Fig. 3: Slogan featured on Arktos’ homepage

This stylistic transformation has been accompanied by a reprioritisation of content. Arktos’ hitherto focus on commissioning original or translated books has been increasingly coupled with, or even transplanted by, the publication of short-form online pieces. Articles previously featured in its webzine, Arktos Journal, appear to have altered from an innovative supplement to the main attraction (see Figure 4). Arktos has declared its commitment to present daily material on “topics that will inform, inspire, and entertain”. The remit of its articles is expansive; one needs only note its list of “15 Homogeneous European Cities Worth Exploring”, a twist on the conventional travel op-ed.

Fig. 4: Daily content featured on the Arktos website

In lieu of the decline in Arktos’ prior capacity to readily print books, the publishing house has turned its attention towards alternative revenue streams, notably revealing alongside the advent of its website a subscription-based model. Arktos has promised additional content, exclusive events, and the provision of a free monthly eBook or audiobook, contingent on the form of membership purchased: bronze, silver, or gold. Artkos has also declared an intent to double its output and relaunch its faltering podcast, the ‘Interregnum’, upon reaching 500 subscribers.

Arktos has been vocal in promoting its new system, even implementing a launch discount to entice subscribers. The group has also utilised its presence on several mainstream and alternative social media platforms, which it uses almost exclusively to advertise its products. Arktos’ Facebook profile has garnered approximately 40,000 likes, alongside 3,500 Instagram followers. Meanwhile, Artkos has approximately 1,500 followers on Gab and 2,800 Telegram subscribers. Each platform receives regular, increasingly daily, updates showcasing its newest material.

This subscription-based service has been coupled with additional funding sources. While Arktos previously crowdsourced individual projects, it has now turned towards general donations, with a preference for cryptocurrencies, to rebuild its distribution network and reinvent Arktos as a “think tank” and “complete media operation”. In addition, merch emblazoned with far-right iconography has been a staple since Arktos’ inception. In 2010, the Artkos homepage read: “Turn your revolt into style”. While the website until recently still advertised an Arktos mug and “Julius Evola T-Shirt”, such products are currently unavailable, and the digital shop is otherwise empty. Lastly, the new website alludes to what it intends to be a flagship initiative – ‘Arktos University’. However, beyond a somewhat innocuous statement that it is “coming soon”, precisely what this university entails is shrouded in mystery.

Conclusion

Artkos publishing house has demonstrated an ability to evolve and innovate. Since its foundation, Artkos has transformed from a self-professed “obscure start-up company to one of the major pillars of contemporary traditionalist and anti-globalist literature”. However, at the core of this transition has been its production and sale of books which was made impossible with Ingram’s decision to terminate Artkos as a client in 2023.

While Arktos has endeavoured to redress its current predicament by reinvigorating its website and increasingly prioritising daily content production—shifting from its original role as a publishing house to an online think tank—it is evident that Ingram’s cancellation of Arktos’ account had imposed a significant setback on the latter.

Arktos has managed to gradually reinstate the distribution of many of its paperbacks. While it is unclear how this has been achieved, it is likely that Arktos simply migrated to another print-on-demand provider. While Breivik’s directions are a testament to the ability of white supremacists to manipulate the ubiquitous distribution networks, ready accessibility, and comparative lack of moderation associated with print-on-demand services, the case of Ingram should provide a countervailing example of the impact that deplatforming can hold for distributors of far-right material. However, in order to militate against migration among mainstream providers, more rigorous practices of content moderation and cooperation between such services, including the likes of Lulu.com and Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing, will be required.

Kye Allen is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford. His dissertation explores the history of Anglophone fascist international thought during the twentieth century.

@KyeJAllen