Introduction

The 2019 terrorist attack in Christchurch, New Zealand revealed the importance of the transnational circulation of memes for online extremist mobilisation. During the attack, the terrorist streamed a video on Facebook which started with a car ride, during which he was listening to a war song celebrating Serbian combatants and their leader Radovan Karadžić in the fight against Bosnian Muslim and Croatian adversaries. The song, recorded during the wars in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, constructs a new narrative of the wars and locates the first instance of the so-called European ‘white genocide’ in the Balkans. The song was later coopted by extremists and turned into an Islamophobic meme titled ‘Remove Kebab’. The Christchurch attacker referred to himself as a “kebab removalist” in his manifesto and painted the slogan on the semi-automatic rifles used during the attack.

The role of memes in far-right movements is well documented in scholarly literature. One of the most popular memes of the American alt-right, Pepe the Frog, received significant media and scholarly attention, unpacking its origins, meaning and symbolic use in far-right networks (Krämer et al., 2020; Miller-Idriss, 2019). The Remove Kebab meme received much less scholarly attention (with some exceptions), despite its popularity on far-right platforms like Gab.

This Insight unpacks the process behind the creation of the meme, which has served as a tool for radicalisation and incitement to hatred and violence against Muslims. In particular, I am interested in the processes of memetic transformation, imitation, iconisation and narrativisation, which turned the war song into an Islamophobic symbol in digital media.

From Bihac to Petrovac Village: The Far-Right in Former-Yugoslavia

During the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, the far-right flourished. Radical right parties and extremist organisations in Croatia (Croatian Party of the Rights, Croatia Pure Party of Rights) and Serbia (Dveri, Zavetnci), as well as Islamist organisations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, are still active in the region. These groups have embraced the use of social media, sharing with other far-right groups the conviction that “solving the conflict is only possible by eliminating ‘the other’, metaphorically or literally”. The current resonance of the Serbian radical right with other far-right groups rests on shared Islamophobic sentiments and the narrative of ‘freeing’ Europe from Muslims. This Insight focuses on the Remove Kebab meme and the meaning creation and transformation of a patriotic, turbo-folk song ‘From Bihać to Petrovac Village’ into a far-right meme after it was uploaded on Youtube in 2006.

According to Knowyourmeme, the song was recorded in the town of Knin, in today’s Croatia, between 1993 and 1995, during the wars in former Yugoslavia. The video features four soldiers in uniforms playing a folk song in honour of the then-president of Republika Srpska (RS), Radovan Karadžić, later convicted of genocide in Bosnia. The song was part of the broader turbo-folk genre, described as “the Serbs’ exotic and hyper-sexualised ‘soundtrack for genocide'”. The lyrics illustrate an existential crisis, depicting a threat to Serbian land posed by the enemies – Croats and Bosnian Muslims – and proposing a heroic defence. The song calls upon Karadžić to lead the Serbs into battle and to show their fearlessness. The video is amateur in design and production, confirming that bad videos make good memes, as they invite parody and edits.

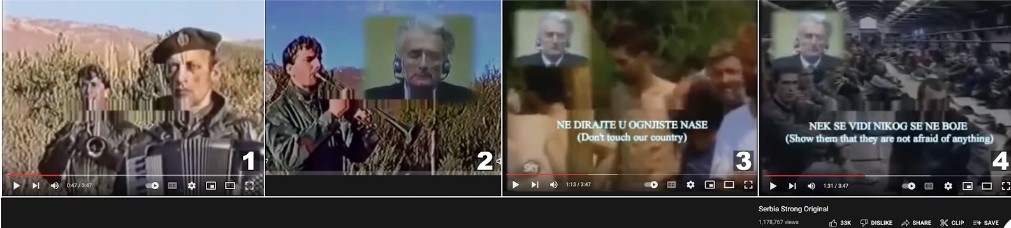

The first variation of the song was uploaded to YouTube in 2006 as a ‘remix’ with inserted images of Karadžić in the courtroom of the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The video also included a set of iconic images from the Bosnian war – the camps of Trnopolje and Manjača (Fig.1, Frame 3 & 4). In August 1992, these images were published in prestige outlets, from the cover pages of Time Magazine, the New York Times and the Guardian, causing serious outcry and sparking debates on the coverage of the Bosnian genocide in Western media. If this version was created by Croatian film director Pavle Vranjican, as claimed in some internet forums, then the effect of the iconic images was to contrast the heroic narrative of the lyrics with a visual depiction of the atrocities. Hence, this remix changed the meaning of the song, turning it into a parody critiquing the original, derisive of the goal declared in the song.

Fig. 1: Video ‘Od Bihaća do Petrovca sela’ edited with iconic images from the war in Bosnia

In response to this version, another remix of the video was uploaded under the title ‘Serbia Strong/God is a Serb’, where the atrocity images were removed and the lyrics were translated into English. This version was directed towards the promotion of Serbian war efforts, although some comical elements – such as clips of Karadžić sipping coffee – remained.

In March 2019, after the Christchurch attacker’s direct reference to the song, the original video, with 9 million views, was removed from YouTube. Despite this, the video is constantly reuploaded by other users, and there are currently dozens of different versions still available on YouTube. Between the ‘Serbia Strong’ remix and the Christchurch attack, another significant transformation took place, turning one image from the video into an icon accompanied by the Remove Kebab slogan, which thus became a far-right meme and symbol of the fight against ‘white genocide’.

From War Song to Meme

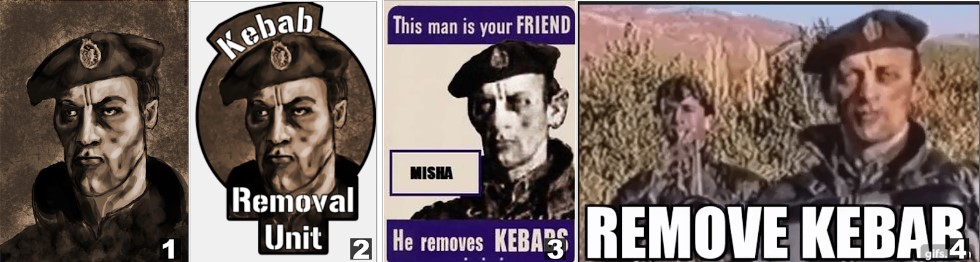

The second process of transformation that enabled the universalisation and virality of the meme was its transformation from a video to an image. One of the most popular variations of the meme was created in 2011 by an art student, who created their own artistic version and added text (Fig. 2, frame 1). The slogan, ‘Remove Kebab’, goes beyond the meaning intended in the song; ‘remove’ explicitly invokes physical expulsion, while ‘kebab’ metonymically stands for any Muslim, enabling the transition from particular enemies in war to the universalised other.

Fig. 2: Examples of Remove Kebab/Serbia Strong meme

In another iteration (Fig. 3), an illustration of a Serbian soldier popularised on 4chan, is inserted onto violent images of atrocities during the Yugoslav wars. Such examples include images of a mass burial site in Srebrenica (Fig. 3, Frame 1) or an image showing a Serbian soldier kicking the dead body of a Bosniak woman in the town of Bijeljina (Fig. 3, Frame 2). This is an iconic image of the Bosnian War, often praised as revealing the true nature of the war.

Fig. 3: Memetic use of iconic photographs from the war in Bosnia [graphic scenes of violence have been blurred]

Although some intention vis-à-vis memory creation is already visible, to fully understand the narratives that are only signalled in the memes, one needs to analyse the broader social context within which they are produced, namely the imageboard forums and the broader far-right community. Following Ruth Wodak (2015), I focus on four categories, namely (i) threat, (ii) enemy, (iii) reversal of victims and perpetrators and (iv) solution.

The transition of the threat to Serbian land from specific ‘Ustasha and Turks’ – as enemies are called in the song, referring to Croatian fighters and Bosnian Muslim forces – to the threat Muslims supposedly pose to Christian countries worldwide, constitutes the key transformation that makes the Remove Kebab meme indispensable for the far-right globally. Serbia is depicted as the first victim of white genocide, losing its territories in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo to Muslims and exemplifying the main threat Europe is facing. The genocide in Srebrenica is framed as a defensive battle, fought on behalf of white, Christian Europe, turning the atrocity into a moment of pride and glory, and the perpetrators into victims.

Within the meme, the glorification of genocide against Muslims and its transformation into a source of pride comprises visual cues, like the illustration of the soldier over the Srebrenica burial photo, and textual formulations praising Karadžić. Several threads on 4Chan/pol describe Karadžić as “one of the great heroes and martyrs of today’s age” who “removed a lot of kebab”. Similarly, the manifesto of Anders Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 terrorist attack in Oslo, paints Karadžić as a true European hero and “honourable Crusader” for his efforts to “rid Serbia of Islam”. It is within this broader context that, in far-right circles, Serbian war criminals become defenders of Europe against Muslim invasion.

Global Circulations

As the meme went viral, Remove Kebab was shared and reappropriated around the world. Aside from the disturbing instance of the Christchurch shooter playing the song in his car before the attack, other examples include a video of five Chinese soldiers singing the song (Fig. 4, Frame 1), and an incident involving a Chicago police radio getting hacked and jammed with the song (Fig. 4, Frame 2 & 3).

Fig. 4: The global circulation of the Remove Kebab song

These examples, although revealing its widening use, did not secure the meme’s popularity and global visibility. In September 2019, a Twitter user shared a video of the famous YouTuber Pewdiepie playing Minecraft while in the background the ‘Serbia Strong’ song is being played. With over 100 million subscribers and 10 million views on this video alone, the gaming community might be considered one of the vehicles for the virality of far-right memes, as documented by Angela Nagle in the case of the alt-right.

The creation of the Remove Kebab meme, its virality and worldwide circulation reveals the extent of the reach of far-right digital networks. At the same time, it points to the labour of far-right actors who are continuously transforming the content and securing its circulation. Finally, it shows the creation of a new memory of the Yugoslav wars, which are depicted as an instance of ‘white genocide’, while violence against Muslims and the genocide in Srebrenica are evaluated as examples of the heroic defence of Europe. Digital media facilitated this broad memetic protest, turning Remove Kebab into a potent symbol of Islamophobia and incitement to violence worldwide.

Katarina Ristić is a lecturer and senior researcher at the Global and European Studies Institute (GESI), Leipzig University, working on the intersection of history, memory, and media studies. Holding a PhD in history from the Faculty of History, Arts and Regional Studies of Leipzig University (2013), she studied philosophy at the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Belgrade (2004). Her latest research focuses on the visual memory culture and transnational memory activism in digital media.