Introduction

The Islamic State’s (IS) shock and awe campaign launched at the turn of 2014 proved to be one of the major threats to international security emanating from cyberspace. Compared to the earlier manifestations of digital jihad, its productions gained unprecedented quality and popularity worldwide. Effectively, IS‘ online activities were widely perceived as one of the core factors contributing to its global recruitment success. To address this threat, counter-terrorism stakeholders, such as governments and internet firms, have launched multiple P/CVE programs designed to tackle IS’s online appeal. These programs were combined with kinetic attacks against key media operatives of Daesh by the U.S.-led coalition and apprehensions of individuals engaged in supporting IS’ online presence. By 2016, the online activities of IS were visibly reduced, manifesting in decreased output and popularity. This reduction was confirmed by multiple studies that tracked IS’ operations in various online environments. However, with the increasingly evident wavering of IS’ digital capabilities, academic attention shifted elsewhere. Thus, only a handful of studies attempted to closely follow how the Islamic State online propaganda campaign evolved in recent years.

This Insight summarises the findings of a research project mapping the evolution of the pro-IS information ecosystem on the surface web between December 2020 and June 2021. This study focused on exploring the most important IS propaganda dissemination channels, learning their functions, and understanding how channels mutually reinforced the group’s outreach. The complete results of the project can be accessed in the full paper published by the Security Journal.

Methodology

This study utilised a combination of open-source intelligence techniques and limited content analysis and focused exclusively on the surface web. Dark web locations, social media profiles or channels in communication apps were only considered if they were visibly interconnected with or advertised on the surface web. A classic three-stage approach to identifying terrorist domains was used. In the first phase, the study utilised advanced search operators combined with IS-related terminology in English and Arabic. This solution allowed identifying some of the core domains in the information ecosystem of Daesh. In the second phase, all URLs discovered and positively verified for containing IS content were subject to data scraping. The study focused primarily on external links, allowing us to understand which internet addresses were interconnected with a given domain. Reverse IP lookup was also used to identify other domains co-hosted on the same server. This allowed the internal structure of the ecosystem and the mutual interconnectedness of some of its elements to be examined. In the final stage, all newly identified internet locations were subject to similar web scraping. All addresses were coded in the database as either primary – detected with search engines and thus easily accessible for the audience – or secondary communication channels – discovered in stages II and III with web scraping tools.

This investigation was carried out in two phases. The first covered the turn of 2021 (December 2020-February 2021) while the second focused on the IS’s activities in May and June 2021. The findings of both investigations allowed the creation of two separate maps of IS communication channels. These channels were subject to comparative analysis to learn how IS’ information ecosystem on the surface web evolved over six months.

This project had three caveats. First, mapped both active and inactive domains that could be positively verified to contain propaganda supporting the agenda of Daesh were mapped. Second, all outgoing links to a single file-sharing service from a detected URL were coded as one record in the database. Third, upon publication, real internet addresses were removed from both databases and maps. Codenames were used in their stead.

Islamic State’s Information Ecosystem at the turn of 2021

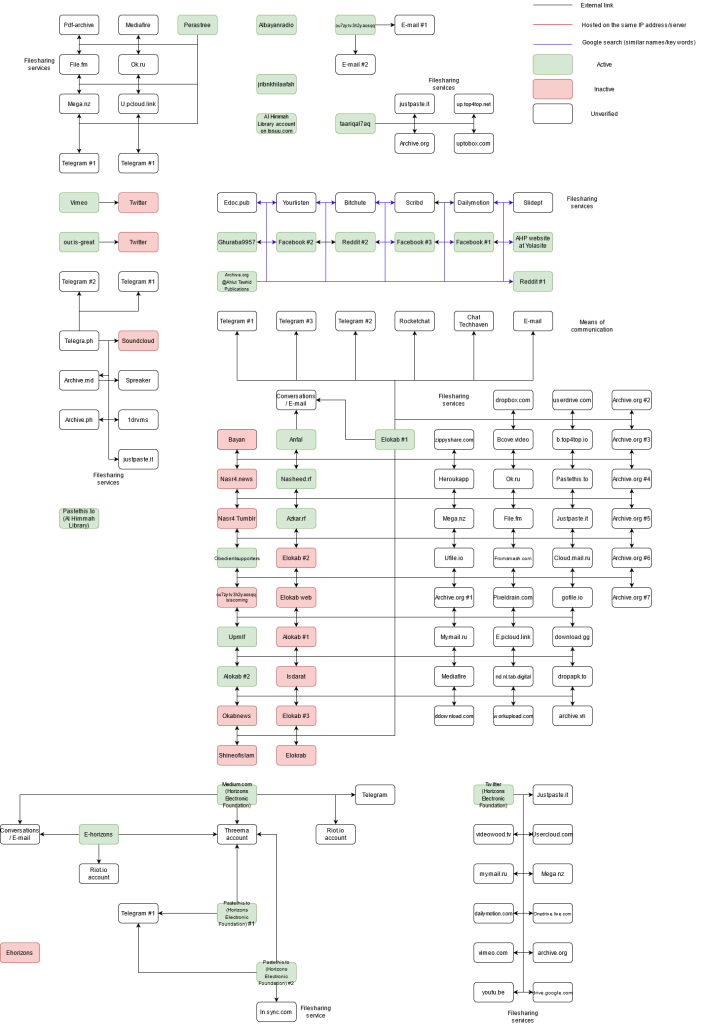

The first phase of the investigation carried out between December 2020 and February 2021, discovered a total number of 130 primarily Arabic URLs directly associated with IS, including 28 standalone websites and blogs, nine social media accounts, 74 file-sharing services and 19 other communication channels. As expected, classic OSINT techniques proved to be inefficient in collecting the most valuable technical data related to the identified domains. All of the channels were professionally anonymised, which indicates the advanced OPSEC standards adopted by the pro-IS propaganda machine. Still, it was possible to map the ecosystem’s structure based on extracting external links, leading to other pro-IS internet addresses (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Simplified map of the Islamic State’s information ecosystem on the surface web as of December 2020-February 2021

The information ecosystem has several interesting features. First, unlike at the apogee of its campaign in 2014-2015, the identified ecosystem proved to be overly centralised. A large part of the ecosystem (51 unique communication channels) was interconnected with Elokab, a standalone domain run by IS supporters. The ecosystem contained a massive number of propaganda productions supporting this VEO. The webpage also served as a hotspot for networking of pro-IS internet users. New posts were met with their numerous comments, which consisted of, among others, links redirecting supporters to other pro-IS websites. Aside from these features, Elokab admins uploaded new releases on multiple file-sharing and streaming services simultaneously, which made them more resistant to content takedowns. Last, Elokab made a significant effort to advertise pro-IS groups on privacy-oriented messaging apps like Conversations or Telegram.

Another essential element of the pro-IS ecosystem at the time was run by Afaaq Electronic Foundation (AEF), which specialised in creating cyber security instructions for IS members and followers. A constellation of its websites, pastebins, and social media profiles was detected, although some sites had already been banned. AEF also showed significant interest in advertising their channels or profiles on messaging apps like Threema and Telegram.

Other elements of the ecosystem consisted of more or less interconnected communication channels, including inactive but still unbanned traces of Ahlut-Tawhid Publications activity, pro-IS blogs in several languages (Somali, Farsi), as well as instances of activity from the official propaganda cells of Daesh: al-Himmah Library and al-Bayan Radio.

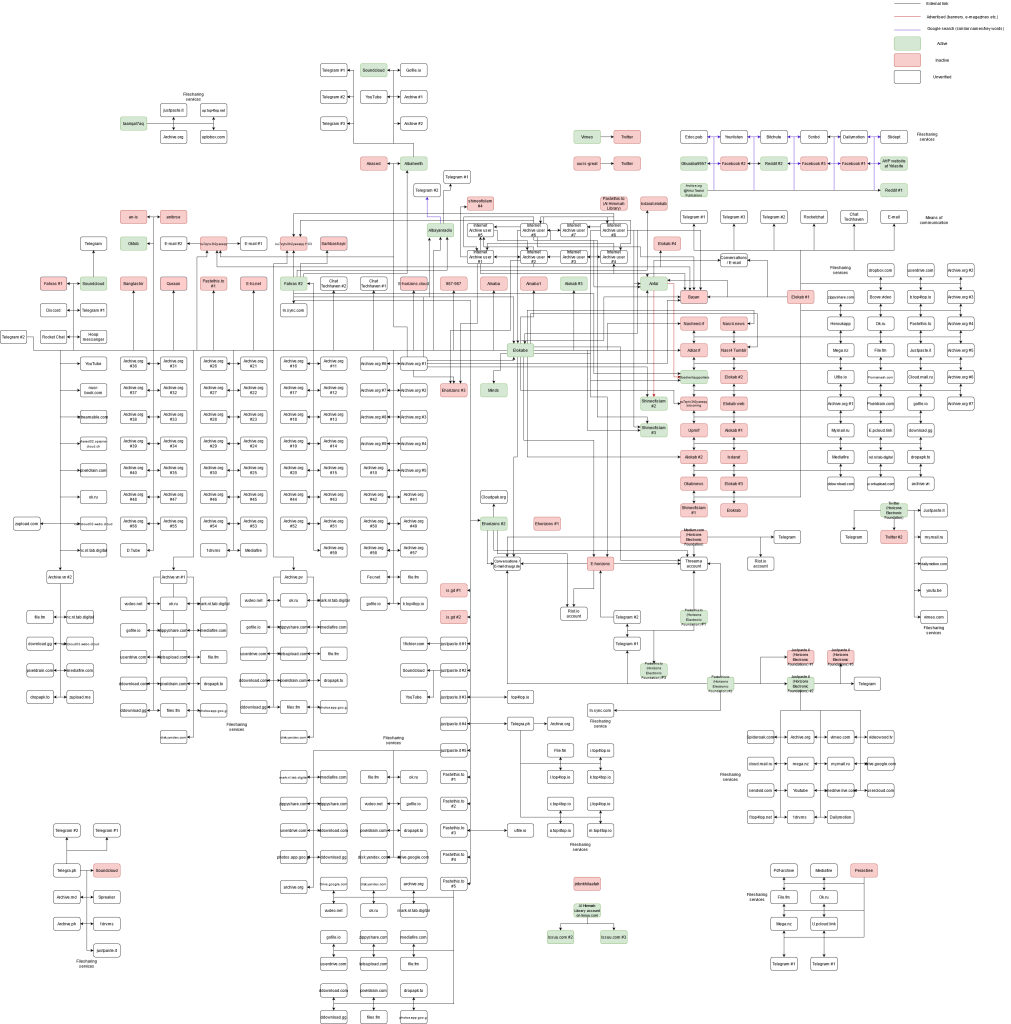

Mapping the pro-IS Ecosystem in mid-2021

The second phase of the investigation in May and June 2021 provided surprising findings. Our investigation detected 386 active and inactive communication channels, including 130 from the first phase. This constellation comprised 56 standalone websites and blogs (15 active), 12 social media accounts (4 active), 238 file-sharing services and 35 other communication channels. Thus, within several months, the ecosystem gained 256 primarily Arabic internet addresses. Collected data suggests that most of these URLs were run by the supporters of Daesh, although activities of official propaganda bureaus could also be spotted (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Simplified map of the Islamic State’s information ecosystem on the surface web as of May-June 2021

There are several notable features of the pro-IS ecosystem in mid-2021. First, a significant number of the previously detected communication channels were banned/inaccessible at the time. This included channels run by Afaaq Electronic Foundations and pro-IS blogs, such as Perastree. Only a handful of these sites survived takedowns, including AlBayanRadio and Anfal. This indicates that the P/CVE community were actively tracking and removing IS propaganda.

Second, the new ecosystem was still concentrated around one of the new mirrors of Elokab (Elokabe). As previously noted, Elokab was a hotspot for propaganda dissemination and networking for the followers of Daesh. However, the Elokabe-related network was much more developed compared to the earlier period, with 134 interconnected URLs. Most URLs were advertised in the comments below each new post. Among others, users of Elokabe shared external links leading to Fahras (‘index website’) that aggregated links to other pro-IS domains. Elokabe also redirected visitors to various blogs and standalone domains, including Shine of Islam and Albaheeth. Interestingly, Albaheeth utilised advanced means of avoiding detection from law enforcement agencies. For instance, Albaheeth used generic visuals related to Islam mixed with pro-IS content. The domain also utilised peculiar punctuation of Arabic terms, which helped circumvent search engine queries. Elokabe also redirected visitors to file-sharing services and one social media profile at minds.com.

Third, similarly to the first phase of research, Afaaq Electronic Foundation had a significant presence. Aside from one standalone webpage, the AEF network consisted of profiles and link aggregators located on a broad spectrum of pastebins, file-sharing services and channels in communication apps, such as Threema and Conversations.

Finally, this investigation phase discovered a network of eight mutually interconnected profiles on the Internet Archive. Surprisingly, the ecosystem fulfilled two functions at the same time. As expected, the ecosystem shared thousands of old and new propaganda productions of the IS. The ecosystem also advertised links to other pro-IS communication channels on the surface web, including, for instance, the websites of AEF. Overall, the whole constellation was designed in a way that maximised access to propaganda and connectivity between various parts of the information ecosystem of Daesh.

Conclusions

The findings from this study demonstrate that the crisis of the Islamic State’s online campaign is more or less over. The group proved capable of rebuilding a significant part of its former presence on the surface web, but in a new, previously unknown form. In contrast to 2014-2016, when the official propaganda machine of Daesh was responsible for leading propaganda efforts, the new, easily accessible ecosystem seems to be primarily run by unofficial media cells and individual supporters. This shift undoubtedly increases the resilience of the group’s propaganda machine. However, at the same time, this shift to unofficial accounts may backfire in reducing followers’ trust in information provided by pro-IS communication channels. IS has experienced trust-related scandals in their ecosystem in recent years that demonstrate this risk.

Other significant changes relate to the nature of the dissemination channels utilised. In contrast to the apogee of the IS campaign, the pro-IS community seems to be much less present in mainstream social media. This shift may be considered a significant success of the content takedown solutions adopted by these services. Instead, IS now prefers encrypted, privacy-oriented communication apps and standalone websites. Moreover, IS are increasingly interested in using file-sharing services, confirming the findings of Stuart Macdonald et al.

Finally, most detected communication channels utilised Arabic as their primary language. English and other languages were relatively uncommon. The dominance of Arabic language channels demonstrates that while the pro-IS community was capable of rebuilding a large part of its former presence in this part of the internet, they could not produce large quantities of propaganda productions dedicated to influencing Western audiences again. Thus, the potential impact of these media efforts seems to be more concentrated on traditional targets of digital jihad, namely users originating primarily from Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia.