Over the past three years, the threat of extremists and terrorists making 3D-printed guns has changed from a hypothetical to a realised scenario. Since 2019, there have been at least nine examples of extremists, terrorists, or paramilitaries making, or attempting to make, 3D-printed guns in Europe and Australia. This unprecedented surge in cases gives a glimpse of a future where such occurrences may become routine. While we have already seen their proliferation among criminals, we are now witnessing extremists worldwide searching for, downloading, sharing, and manufacturing 3D-printed gun designs.

Analysis of these recent cases reveals four insights. First, 3D-printed guns have gained traction among the far-right—accounting for all but one case—with examples appearing in five countries. The only exception is a dissident republican paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. Jihadists, meanwhile, are noticeably absent. Second, many of these cases also involve attempts to make explosives, meaning that 3D-printed guns have supplemented—and not replaced—existing threats. Third, 3D printing is not a shortcut to acquiring a gun, as the process still involves considerable time and effort. It remains to be seen whether their arrival has shortened the attack planning process. Fourth, at least one extremist had joined the leading 3D printing gun forum, using it to obtain guidance on his firearms and explosives, seemingly unbeknown to its moderators.

Nine Examples of Extremists Attempting to Make 3D-Printed Guns Since 2019

The nine cases vary in severity, from individuals possessing the CAD designs (which depending on the jurisdiction, can be illegal) to manufacturing and attempting to use them. All occur in countries where there are relatively strict gun laws: Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK. The FGC (‘Fuck Gun Control’, available in either 9mm or .22 calibre) is the most prominent, featuring in at least five cases. The FGC-9 was first released in March 2020.

The nine cases are:

- October 2019, Halle, Germany: Stephan Balliet, a 27-year-old white nationalist, killed two people using improvised homemade weapons. He posted his designs and manifesto online, stating his intention was to prove their “viability”. His main gun had only a small, cosmetic 3D printed component (the trigger cover). Other firearms, such as a hybrid 3D-printed Luty submachine gun, had more.

- August 2020, Paulton, UK: Dean Morrice, a 33-year-old white nationalist, was arrested for attempting to make explosives and a 3D-printed gun. He had also shared Balliet’s manifesto online. He was convicted in June 2021.

- September 2020, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain: a 55-year-old, known only by his initials ‘J.M.’, was arrested for having a 3D printing gun workshop. Police found 19 3D-printed pistol frames, multiple melee weapons, and explosive precursors. He also had over 30 far-right documents and manuals on urban guerrilla warfare, alongside a holster with a Nazi symbol. It is unclear if he planned to sell or distribute the weapons to other like-minded extremists.

- December 2020, Essex, UK: Matthew Cronjager, a 17-year-old white nationalist, was arrested after trying to secure conventional firearms and 3D-printed guns (an FGC-9 and a Cheetah-9 Hybrid SMG) from an undercover police officer. He planned to kill a non-white friend, and was convicted in September 2021.

- May 2021, Keighley, UK: Three members of a far-right cell were arrested for attempting to make a PG22, a rudimentary 3D-printed gun, as well as explosives. Daniel Wright, Liam Hall, and Stacey Salmon were convicted in March 2022. Another man, Samuel Whibley, was convicted for sharing terrorist material, including gun designs, with them.

- September 2021, Orange, NSW, Australia: A 26-year-old white nationalist—who cannot be named here due to a non-publication order—was arrested after attempting to make an FGC-9. Although the maximum sentence was 14 years, he was given an “intensive community corrections order with supervision for two years.”

- November 2021, Falköping, Sweden: 25-year-old Jim Holmgren was arrested for possessing explosive precursor material and 3D printed gun components. He was a former Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM) member. Police found far-right documents and a purported manifesto.

- February 2022, Schouwen-Duiveland, Netherlands: A 33-year-old man was arrested for making an FGC-9. He had also bought ammunition. Four Nazi flags were found in his house, as well as a Flemish Movement flag.

- April 2022, Belfast, Northern Ireland: Four members of Óglaigh na hÉireann (ÓNH), a dissident republican paramilitary group, attended an Easter Sunday commemoration. One member read a statement while two others brandished FGC-22s (a .22 calibre version of the FGC-9). It was the first time a paramilitary group was seen with 3D-printed guns in Northern Ireland.

[Photos by Dieter Reinisch]

This list excludes the 15-year-old girl in the UK who was arrested in October 2020 for possessing 3D-printed gun designs and documents on explosives. Authorities later dropped the charges after determining she was a victim of trafficking and sexual exploitation. Also excluded is the case of 24-year-old Artem Vasilyev in Adelaide, Australia. At his home, police found an FGC-9 and guides on making explosives. Even though he was charged in September 2021 with terrorism offences, it is unclear from public reporting or police statements whether he holds violent extremist ideas.

The Prevalence of the Far-Right

Eight of the nine cases involve individuals linked to white nationalist or far-right ideologies. Their prevalence has some tentative explanations. Far-right forums and chat groups regularly share digital libraries of ideological and instructional material on improvised weapons and explosives. These libraries may make it more likely for users to come across 3D-printed gun designs. Another factor is the emphasis far-right ideologies place on stockpiling weapons and supplies for a hypothetical ‘race war’. Such preparation can increase the chances of someone coming across—or actively searching for—3D-printed gun designs. Firearms also have a strong cultural draw, as they regularly feature in the iconography and imagery of the far-right.

Another possible explanation is precedence. One far-right terrorist attack has already involved 3D printed components: Stephan Balliet’s attack in Halle, Germany. On Yom Kippur in 2019, he tried to enter a synagogue and kill the worshippers inside using homemade, improvised weapons. Yet Balliet could not get past a locked door, his weapons repeatedly malfunctioned, and his explosives were ineffective. Though he did kill two people, the attack was regarded as a failure among the far-right—not least by Balliet himself. Nonetheless, his manifesto and livestream have resurfaced on the computers of later plotters (such as Dean Morrice and Jim Holmgren). His example possibly inspired them, or served as a lesson of what not to do.

Balliet’s main homemade gun used in the Halle attack, 9 October 2019

A hybrid 3D-printed Luty submachine gun which Balliet had made for his attack

Jihadists are Noticeably Absent

In contrast, there is no known example of a jihadist attempting to acquire or make 3D-printed guns in Europe. While cases may simply not have made their way to the public domain, the absence begs the question: where are the jihadists? There is no definitive answer here. One possibility is that jihadists are much more reactive to propaganda, which thus far has encouraged other attack methods such as stabbings, TATP explosives, and vehicle rammings. A wave of such attacks in Europe has only reinforced those methods, meaning that future attackers may emulate these tried and tested methods rather than experiment with 3D printing. Gun designs also do not appear to be shared in jihadist spaces as much as they are in online far-right ecosystems. Those explanations notwithstanding, why jihadists have not yet attempted to use 3D-printed firearms remains a mystery.

The Continued Fascination with Explosives

Even in these nine examples, 3D-printed guns are not always the sole focus. Explosives remain highly desired and feature in five cases; all obtained their guidance from online manuals. The underlying issue here is therefore the prevalence of instructional material online. They may be taking inspiration from infamous terrorist attacks, such as the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, the 2011 Norway attacks, or those of the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. Holmgren, for example, asked questions in one online forum on how to make various explosive materials and had precursor chemicals at home. Dean Morrice, meanwhile, had stockpiled enough precursors to produce 680kg of thermite. The Keighley cell also had “an active interest in the manufacture of explosives,” with precursors and instructions found in their homes. The same is true for ‘J.M.’; alongside his arsenal of 3D-printed guns, he was reportedly testing explosives in the mountains of Tenerife. The advent of 3D-printed guns has therefore not displaced traditional threats, but supplemented them.

The Keighley cell’s attempt to make explosives

3D Printing a Gun is Not a Shortcut

These cases also show that 3D-printing does not currently present the ‘path of least resistance’ for a would-be attacker looking to obtain a weapon. Printing and assembling a gun still involves considerable time and energy. There are several necessary steps: acquiring the correct printer, software, and polymers; sourcing the most suitable designs; printing and assembling the components (some parts, such as firing pins or recoil springs, cannot be 3D printed and so would need to be sourced elsewhere); buying or making ammunition; and finally testing the gun for accuracy and reliability. The need to avoid detection by the authorities only compounds these practical challenges. No one operates at maximum efficiency, and each step in the process can frustrate or dissuade those less committed.

However, we do not know the number of extremists who considered—and ultimately abandoned—the idea of using 3D-printed guns or components. The Buffalo shooter is perhaps the only known case in point, although there are likely other examples. On two occasions, Payton Gendron wrote in his online diary how it might be possible to 3D print a component to allow a semi-automatic gun to fire automatically. Ultimately, he did not proceed with this idea (his first thought was to use pliers or a hydraulic press instead). Gendron could accomplish his goals with legally obtainable firearms, after all.

The 3D-Printed Gun Movement

The movement behind 3D-printed guns is diverse in its aims and motivations. Not everyone is involved for ideological reasons, though there is a broad libertarian undercurrent of opposing State intervention into citizens’ lives. While the general aim is to ensure anyone can make a firearm, the main forums and communities do not actively encourage violence against the State (or other groups). Beyond the universal right to bear arms, they do not endorse extremist ideologies or groups. In a Popular Front documentary, JStark, the founder of the leading network behind new 3D printed gun designs, shared his thoughts on extremists:

“We kind of don’t like extremists because they usually start a fierce conversation or debate … We like to discuss actually designing firearms, and actually advancing the cause [of the right to bear arms] … But in general, we do not like racists, we do not like xenophobes. We just like people who are for the cause of the right to bear arms and for freedom of speech”.

Ideological or political discussions are discouraged in the group’s chatrooms and are moderated and censored when they occur. However, this does not mean that the network cannot be exploited by extremists who remain incognito. When asked about the risk of extremists infiltrating the community, JStark replied:

“So basically, we let everybody in but if they act up we kick them [out] … If they never talk about politics, if they never show indication of xenophobia or of being zealots, how the fuck are we supposed to know that we have to kick them out? But if they do show that they are extremists, racists, Islamic terrorists, then we would kick them out immediately”.

Extremists Using the Principal 3D-Printed Gun Network

At least one violent extremist has already exploited this lax security. Jim Holmgren, a 25-year-old white nationalist, was arrested on 4 November 2021 at his farm in Falköping, Sweden. Police found 50 tonnes of precursor explosives on the farm, where he lived alone, though a portion of those belonged to his neighbour. There were also far-right paraphernalia and documents, including a purported manifesto paying tribute to Anders Breivik. According to his indictment (not in the public domain), Holmgren bought a 3D printer in January 2021 and tried making three semi-automatic 3D-printed firearms. His house was littered with parts for the ZBC-21 (a bullpup carbine, also known as the Urutau, in beta testing), FGC-9, and FGC-22. He also experimented with several other designs, such as the PG22, Covid-22, SpaceJunk V2, and Songbird.

He had sourced the files from the foremost 3D-printed gun community, where he was an active poster in its various RocketChat rooms. Holmgren asked questions about making 3D-printed guns and conventional explosives, and was also involved in chatrooms exclusively for beta testing. He used three different usernames. None appear to have been used contemporaneously, suggesting that he either lost access to accounts and created new ones or wanted to switch accounts to avoid surveillance. (His final username had 129 logged visits between June and November 2021). As none of his posts revealed his ideological leanings or ultimate intentions, the administrators and moderators were seemingly oblivious to his attack planning. Those intent on making designs accessible to the public may merely see this as a necessary ‘cost’ of spreading the message.

Holmgren was charged with “gross public destruction” (grov allmänfarlig ödeläggelse) rather than terrorism, as he had no fixed plan or target. Though he was acquitted of this in June 2022, he was convicted of a weapons charge and violating laws on explosive and flammable goods. He is currently awaiting sentencing.

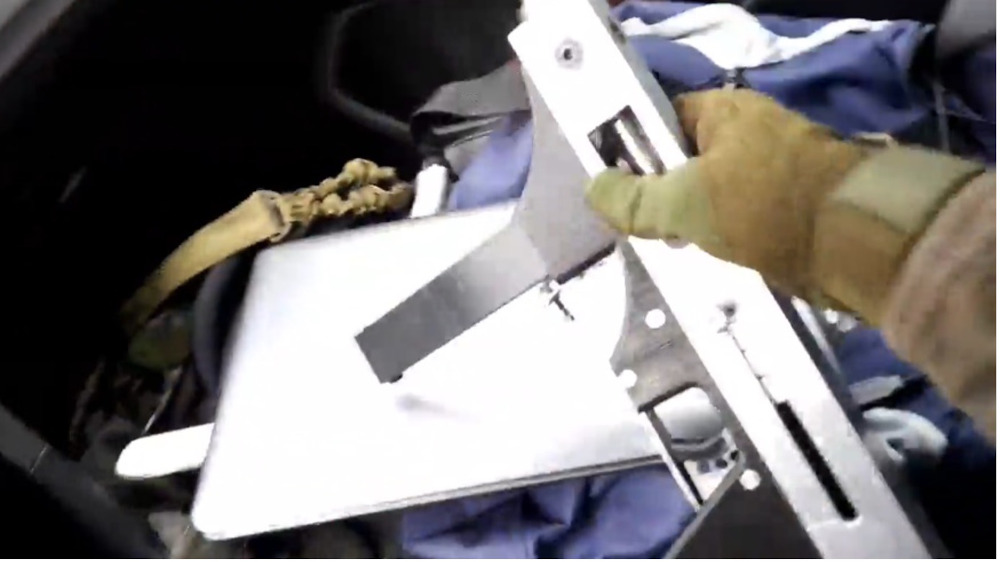

Jim Holgren’s 3D printer, alongside some firearms components

Tactical Innovation in Terrorism

Tactical innovation in terrorist attack planning can rely on a ‘breakthrough moment’. That can be via the release of propaganda or a high-profile attack, which signals to other extremists that this new method works. Jihadists saw this occur with vehicle rammings, which were first encouraged in Al Qaeda’s Inspire magazine in 2010. Several attacks followed. The highest profile was the July 2016 attack in Nice, where Mohammed Lahouaiej Bouhlel used a 19-tonne truck to run over scores of people at the seafront promenade, killing 86. Copycat attacks in Berlin, London, Stockholm, and Barcelona used a similar modus operandi. Another breakthrough occurred with far-right terrorists using livestreams to broadcast their attacks. Copycats followed the example of Brenton Tarrant, who live-streamed himself killing 51 people at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, in March 2019. The effect was enormous, and subsequent far-right attacks in Poway, Bærum, Halle, and Buffalo all involved perpetrators who also attempted to livestream their shootings.

Maintaining Perspective Amid the Alarm

3D-printed guns have not yet had this breakthrough moment. However, the recurrence of plots since Halle shows that such a breakthrough may not be necessary. Despite this flurry of cases, it is essential to maintain perspective. Improvised, homemade firearms—and documents instructing people how to make them—have long predated the rise of 3D printing. The vast majority of the hobbyists and enthusiasts of 3D-printed guns likely have no intention to use them for terrorism. Even then, the greatest threat does not appear within this community but rather from existing extremists coming across—or deliberately searching for—their designs.

Prospects

That said, it remains to be seen whether the pace of cases will slow down. The technical knowledge needed to make a gun is decreasing, and 3D printers are relatively inexpensive. Tried and tested designs are freely posted online, with step-by-step instructions on printing, assembling, and testing the guns. Regulation also does not appear able to restrict the component parts and materials. Beyond any technical aspects, 3D-printed guns are moving into the mainstream. They are found across social media and can potentially become, if they are not already, cultural mainstays and highly-desired items in extremist—and criminal—subcultures. The situation today is far from what it was when they first emerged a decade ago, when they were bulky, unreliable, and only a niche interest. There is no going back to an era before 3D-printed firearms. The technology is only improving, and it is here to stay. Extremists, terrorists, and paramilitaries are realising that too.