Near the end of January, Islamic State fighters began their siege on Ghweran Prison in Hasakah, Syria followed by a nearly-week long battle by Syrian Democratic Forces to regain control over the prison. CNN reported it as the “biggest coordinated attack by ISIS since the fall of its so-called caliphate [in 2019].” Coordination involved the use two suicide bombers in what Craig Whiteside described as a “surge operation.” Despite IS claims in their weekly Al Naba editorial that it freed hundreds of prisoners with a fighting force of only 12, the exact numbers currently remains unknown. Researchers have expressed concern over the likelihood of similar future attacks given that IS is aware that the SDF remains under resourced and strained but they caution against drawing conclusions that this marks the start of a renewed insurgency.

Regardless of the true numbers of prisoners IS succeeded in freeing, the event has re-invigorated IS supporters in online spaces and as Charlie Winter highlights, the symbolic significance cannot be overlooked. This Insight will focus on a component of unofficial propaganda outputs posted by IS supporters throughout Telegram and contextualise it within qualitative research frameworks.

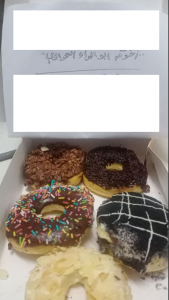

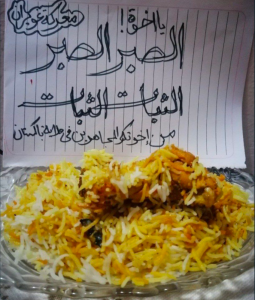

Days after the siege began, pro-IS communities circulated handwritten short messages and longer letters expressing their excitement over news about the attack on Ghweran Prison. Many senders included their country of origin and placed their notes in front of various types of food. A pro-IS channel that reached a following of 19K+ subscribers acted as a major collecting point for these notes and letters. It provided information for a direct contact bot and cautioned supporters in Arabic, “I wish the honourable brothers who sent us pictures of congratulations and blessings for what happened in Ghweran not to share them on social media! When you send us pictures, we change some settings for your safety…” Another post stated, “The congratulations of Muslims from all over the world continue to reach us [and] the lions of Hasakah…your brothers in the land of Sudan, Somalia, Idlib, Aleppo, Iran, Jordan, Baluchistan, Algeria, and even from the Sultanate of Oman are watching you.”

In addition to messages shared by this channel, photos of handwritten notes further seek to add a sense of connected unity and intimacy across virtual networks despite geographical distances between those who submitted content. Posting an anonymous message of support from an untraceable account constitutes a lower threshold of participation than taking a picture of a personally hand-written note next to a meal you are about to consume. Additionally, although many users understand how to maintain operational security online, there is still room for making a mistake which increases personal risk to a certain degree. For example, there have been cases where individuals forgot to remove geolocation tags or identifiable markers in the background.

This pattern of note-sharing behaviour may recall online IS communities’ actions preceding Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s 16 September 2019 final speech where supporters posted handwritten renewed-ba’yahs (pledges of allegiance). It will be interesting to see if future instances of personalised message photos occur and if so, this may indicate a pattern of specific online behaviours demonstrated by IS supporters that are directly tied to real-world events they deem ‘noteworthy’ – pun intended.

I collected a total of 40 notes and letters with users claiming to be from 12 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, India, Iraq, Lebanon, Maghreb (no specific country mentioned), Pakistan, Palestine, Syria, Sudan, and one message in Spanish (no specific country listed). One post claimed messages were also from Belgium, Libya, Somalia, Tunisia, and Turkey but since I did not see the actual notes, I do not have archived photos for them. Some included references to Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. The following are examples of the various messages which were often paired with food:

Placing this developing phenomena within qualitative research, ‘notesharing’ can be classified within Michael Krona’s category of “collaborative identity through participatory media” where “more autonomous supporters and independent entities of the virtual caliphate” find new and creative ways to formulate a “collective identity processes.”

Online words of encouragement, whether through text or photos, are quite separate from forms of material support and it occupies an aspect of what Thomas Hegghammer terms “jihadi culture” defined as “products and practices that do something other than fill the basic military needs of jihadi groups.” Heggammer offers two primary functions of “jihadi culture”: 1) “it serves as a resource for costly signs” and 2) “cultural products and practices serve as emotional persuasion tools that reinforce and complement the cognitive persuasion work done by doctrine.” In this case, the notes and letters convey the clear message that IS remains and supporters all over the world pray for its success (i.e. Heggamer’s second point).

A particularly noticeable aspect of the sample images above includes a focus on food in the background. In her book Hate in the Homeland, Cynthia Miller-Idriss describes the symbolic meaning food carries because of its ability to “embed messages about identity, tradition, culture…” and she identifies a gap in the research on extremism regarding how it can “play a role in extremist identities.” For these IS supporters, many of the food items reflect the countries they claim to be from (i.e. identity, tradition, and culture) in their handwritten message. Table settings convey an inviting welcoming sense to fellow adherents and the presence of these various meals in conjunction with the notes express celebration for an accomplishment that should be enjoyed over food. [As a quick aside, it is worth mentioning that Amaq photo releases have included images of fighters bonding around and sharing food with one another from various wilayat.]

In addition to the handwritten messages circulated before the release of al Baghdadi’s final speech, these notes and letters mark another cluster of data points where repeat behaviours by pro-IS supporters can be observed. Following future posting trends will allow for greater insights on decentralised online identity formation of extremists and how ‘jihadi culture’ forms in this wider context.