Research has overwhelmingly found that central offline events influence online activity and highlight an important interaction between people’s on- and offline worlds. Less is known about the connection between these two environments and the practices of extreme right-wing communities in particular, and extremist communities in general. Instead, empirical studies have tended to focus on how critical events influence the life trajectories and activities of the extreme right in the offline world, the association between the text and messaging of terrorist groups and offline actions, and the link between U.S. presidential rhetoric and political violence. Some recent research has also considered the impact of trigger or galvanising events, such as riots and terrorist attacks, on hateful content online. The role of political elections as trigger events has also become an area of research in part because of the rising popularity in far-right politics and ideologies in the Western world. The primary focus of this scholarship has been on the relationship between tweets about the 2016 U.S. presidential election and hate speech on Twitter as well as the growth of alt-right networks on Twitter and 4chan in response to Trump’s election victory. But in light of these important contributions, less is known about the extent to which divergent presidential election results trigger or mobilise the extreme right online.

This study sought to assess the role of presidential election results as triggering events affecting the posting activities of participants within an extreme right online community, as research has shown a connection between social-political events and spikes in racially-motivated actions, both online and offline. Our emphasis here is on whether political defeat and deprivation or political victory and encouragement (i.e., the 2008 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections of Obama and Trump, respectively) impacts users’ posting activities on Stormfront, the largest white supremacy web-forum.

On the one hand, many theories argue that political defeats motivate the losing side to increase their mobilisation. Research in this regard has found that online activity in general and hateful activity in particular increased in digital platforms of the extreme right following Obama’s election victory in 2008 as a result of a perceived political defeat. Research also suggests that it is common for right-wing extremists (RWEs) to express the need to be prepared to mobilise during times of social-political uncertainty, oftentimes by participating in paramilitary preparations and stockpiling firearms, among other necessities. Here discussions about the right to bear arms, for example, are commonly found in online communities of the extreme right, including following the election of the first African American president who was perceived by the extreme right as supporting gun control.

On the other hand, well-established models claim the winning side may feel encouraged and thus increase their mobilisation. Such perspectives are supported by previous research findings in that, within extreme right-wing digital spaces and in online discussions, online activity and hateful activity increased following Trump’s election victory in 2016 as a result of a perceived political victory. Reports also suggest that Trump, who during his election campaign was concerned about protecting the rights of gun owners, was supported by the extreme right in part because of his stance on gun rights. Indeed, the right to bear arms is rooted in extreme right-wing ideologies.

While the two competing perspectives noted above have well-established theoretical foundations in the terrorism and criminology literature, what remains unknown is which may be more influential in mobilising the extreme right online: (1) political defeat, deprivation, and/or strain, or (2) political victory, and encouragement? We examine these diverging perspectives by measuring the effect of the 2008 and 2016 election victories of Obama and Trump on the volume of postings (i.e., total posts, RWE posts, and firearm posts) on Stormfront via ARIMA time series using intervention modeling. We analysed all open source messages that were posted on the forum 120 days before and 120 days after each election event, which consisted of 765,573 posts for the 2008 election and 256,867 posts for the 2016 election. Several conclusions can be drawn from this analysis.

First, and surprisingly, we found no significant change for firearm posts on Stormfront following either presidential election. Perhaps the forum is not a hotbed for discussions about firearms generally, which to some extent is surprising given that previous research suggests that ingrained within extreme right-wing ideologies is an unrestricted right to own firearms for personal liberty and survival purposes as well as the need to be prepared for attacks, oftentimes through paramilitary preparations, training, and stockpiling supplies including firearms – especially during times of economic and social uncertainty. This finding does, however, align with Holt and colleagues who conducted a content analysis of thousands of posts from eight RWE forums and similarly found few firearm-specific posts and a small portion of posts related to anti-gun control sentiments. On the other hand, the extreme right is a diffused movement encompassing virulent racists, and those with less racist tendencies who are most fearful of the federal government. It is possible the virulent far-right racists gravitate to Stormfront, while perhaps those most concerned about firearms are attracted to more specific gun focused sites. Regardless, this finding requires further exploration.

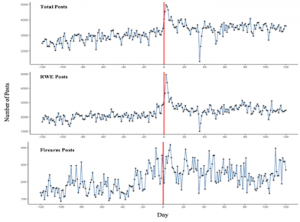

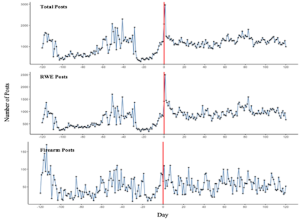

Second, the results of the current study reveal similar posting patterns on Stormfront following the two presidential elections, with a significant and sizeable increase in the total posts and RWE posts following each intervention event (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Time series plot of postings on Stormfront during the 2008 U.S. presidential election.

Notes: The vertical line indicates the election day in 2008. The x-axis is 120 days prior- and post-election. The series for Firearm Posts has a Y axis that is much lower than Total Posts or RWE Posts.

Figure 2. Time series plot of postings on Stormfront during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Notes: The vertical line indicates the election day in 2016. The x-axis is 120 days prior- and post-election. The series for Firearm Posts has a Y axis that is much lower than Total Posts or RWE Posts

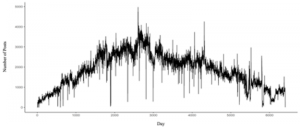

This suggests that there is a link between the general political climate, the current administration, and posting activity of the extreme right on Stormfront. While this finding aligns with empirical studies that have measured the impact of key social events on hateful sentiment and activity of the extreme right online, whether it is the impact of trigger events or U.S. presidential elections, this is a noteworthy finding because, despite the fact that posting activity on Stormfront has been decreasing for quite some time (see Figure 3), forum users in our study were responsive to two opposite events that produced similar results. On the one hand, when presidential candidates (e.g., Trump) make political claims that are in support of the views of the online users, they may collectively believe that their viewpoints are not at the fringes and may feel empowered. On the other hand, when candidates (e.g., Obama) make political claims divergent from the views of online users, they may feel marginalised and express the need to mobilise against the perceived threat. But regardless of each event, in response to each election, Stormfront users melded together for the purpose of collective action.

Figure 3. Distribution of postings on Stormfront from 2001 to 2017.

Most notably is that the number of postings for all three impact measures is much higher for the 2008 election than the 2016 election, and the postings are noticeably elevated during the Obama election year compared to those during the Trump election year. In other words, the extreme right on Stormfront appears to be emboldened by Trump in the run up to the 2016 election and their persistence after his election victory supports that assessment, but the online community is much more active both before and after the Obama administration took the Oval Office. Empirical studies have similarly found that Obama’s election victory in 2008 amplified racial threat effects among white Americans as well as resulted in an increase in the advocacy of hostility and violence on several hate blogs. Researchers have likewise noted that the fear of political and cultural change on part of the Obama administration served as a “tipping point” for the extreme racist right-wing movement specifically or far-right movements more broadly. Our analysis of both election results lends empirical support for this claim: during times of political defeat and, by extension, uncertainty that threatens the existence of the white race, online discussions from the extreme right are driven by perceived harms in the offline world (i.e., Obama as president) much more so than external events working in their favour (i.e., Trump as president).

Together, political defeat and deprivation seems to have a bigger impact on the mobilisation of the extreme right online than political victory and encouragement. But this begs the question of whether these escalations are restricted to the online space or whether it is also mirrored in offline behaviour. Future research should attempt to assess this important on- and offline dynamic by addressing the question of intention relative to action, perhaps by comparing the list of users who were active during either election year with existing data on those who have engaged in both legal movement activity (e.g., rallies, leafletting) and violence offline. Comparing these authors’ online presence may provide the much-needed insight into online activities that may emerge in the offline world and aid law enforcement and others charged with maintaining public safety.

For much more on these findings and the nature of the study in general, we encourage you to read the full manuscript which was recently published in Deviant Behavior.

Ryan Scrivens is an Assistant Professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University (MSU). He is also an Associate Director at the International CyberCrime Research Centre (ICCRC) and a Fellow at VOX-Pol and GNET.

George W. Burruss is an Associate Professor in and Associate Department Chair of the Department of Criminology at the University of South Florida.

Thomas J. Holt is a Professor in and Director of the School of Criminal Justice at MSU.

Steven Chermak is a Professor in the School of Criminal Justice at MSU.

Joshua D. Freilich is a Professor in the Criminal Justice Department and the Criminal Justice PhD program at John Jay College, CUNY.

Richard Frank is an Associate Professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University and Director of the ICCRC.