Introduction

Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT) is a transnational terrorist organisation that advocates for the establishment of a global Islamic Caliphate. Although it publicly rejects the use of violence, HT’s ideological propaganda has frequently served as a conduit for radicalisation, often facilitating individual pathways into terrorist networks. In contrast to jihadist groups such as the Islamic State (IS), al-Qaeda (AQ), and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—which engage directly in armed insurgency and acts of terrorism—HT does not operate as a militant organisation and officially disavows violent methods. Instead, it has adopted a decentralised organisational model, lacking an operational base, and focusing on the dissemination of ideological narratives, political mobilisation, and the strategic use of digital platforms to advance its objectives. The United Kingdom has played a prominent role in HT’s international outreach; according to a report by the Nixon Center, its British branch is among the group’s most active and influential arms. In January 2024, the UK government formally designated HT as a terrorist organisation, citing growing concerns over its role in radicalisation and its exploitation of online environments to propagate extremist ideologies.

Building upon this global context, it is pertinent to consider the group’s influence within specific national settings. In recent years, the relationship between Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) and violent extremism in Indonesia has come under increasing scrutiny. Investigations have revealed that more than 25 convicted terrorists, including Bahrun Naim—a key figure within ISIS networks—and Munir Kartono, had prior associations with HTI before joining ISIS. While HTI does not directly engage in acts of violence, it has played a formative role in shaping extremist worldviews. This characterisation is echoed in international assessments of the broader Hizb ut-Tahrir network, which has been described as an “incubator for extremism” and a “conveyor belt” to terrorism due to its doctrinal teachings and ideological propaganda. Furthermore, large-scale demonstrations held in 22 cities on 2 February 2025 were suspected to be affiliated with HTI, indicating the organisation’s continued activity in the digital sphere despite its legal proscription.

HT strategically uses digital platforms to propagate its caliphate narrative and recruit sympathisers. This raises a critical question about the extent to which exposure to HT/HTI’s digital content operates as a pathway to violent extremism. Therefore, this Insight examines how HT/HTI leverages technology to sustain its ideological campaign, the ways in which such propaganda facilitates radicalisation processes, and the implications for governments and technology companies seeking to mitigate this influence.

The Digital Strategies of Hizb ut-Tahrir

Founded in 1953, HT long predates the digital age, yet the group has strategically adapted to the online environment since the early 2000s. HT has shifted much of its activity online by creating websites, some of which remain accessible to this day, to spread its ideological narrative and expand recruitment efforts. In addition, the group maintains an active presence on global platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Although banned in countries such as the UK and Indonesia, HT continues to operate across these digital spaces by hosting content on servers located outside restricted jurisdictions and by frequently changing domain names to avoid blocking. These strategies allow the group to circumvent national bans and sustain ideological outreach to global audiences.

Figure 1: A screenshot of a biweekly tabloid used by Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) as a key instrument for ideological outreach following its 2017 proscription. It remains accessible online.

Figure 2: Examples of HT’s social media accounts.

In Indonesia, HTI recalibrated its activities into a digital movement following its official disbandment in 2017. Since then, its online operations have been primarily channelled through its newsletter — a hybrid offline and online publication officially affiliated with HTI. Rather than functioning as a personal blog, the platform operates as a structured propaganda outlet, disseminating the caliphate narrative while simultaneously contesting the Indonesian state’s classification of the organisation as extremist. In addition, its newsletter regularly publishes commentary on both global and domestic socio-political issues, consistently framing them within HTI’s ideological perspective and reinforcing its broader political worldview.

In 2024, Indonesia’s National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) reported blocking over 180,000 pieces of extremist content, much of which was attributed to ISIS, HTI, and Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD). This underscores HTI’s persistent efforts to leverage digital spaces to maintain influence, circumvent legal prohibitions, and sustain recruitment pipelines.

HTI’s digital operations reflect a broader phenomenon within Indonesian Islamic movements, described as Islamic clicktivism. This form of digital activism employs social media, hashtags, memes, and coordinated online campaigns to shape religious and political discourse. The Aksi Bela Islam (212 Movement) exemplifies this trend, having used digital platforms to establish new forms of religious authority outside of traditional organisations such as Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah. This development illustrates how non-traditional actors increasingly mobilise mass support and disseminate religious narratives rapidly within Indonesia’s digital landscape.

Figure 3: A focus group discussion held by GeMa Pembebasan at the Bandung Institute of Technology, illustrating recruitment efforts through campus-based discourse.

Comparable digital tactics are evident in Bangladesh, where HT remains a persistent threat despite being banned since 2009. The group has continued its activities by distributing anti-state propaganda and recruiting university students through online platforms and virtual conferences. For example, in 2023, the HTI-affiliated group Gema Pembebasan held a series of discussions, such as “Khilafah: Sistem Pemerintahan Islam yang Baku” (Caliphate: The Definitive Islamic System of Governance) and “Pemilu 2024: Pesta Rakyat atau Pesta Kapitalis?” (2024 Elections: People’s Celebration or Capitalist Spectacle?), featuring student leaders and Islamist speakers. These events were publicly advertised via social media and illustrate how virtual and hybrid forums remain central to HTI’s recruitment strategy post-ban.

In Indonesia, a comparable pattern has been observed in the activities of Gema Pembebasan, an HTI-affiliated youth wing that has reportedly infiltrated university campuses. To evade law enforcement, HT frequently shifts between digital platforms and strategically disseminates its materials through decentralised online networks, often targeting environments with limited surveillance. Moreover, Bangladeshi authorities have traced financial support for HT from international sources, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and Pakistan. These findings highlight HT’s transnational operational model, sustained by digital networks and diaspora funding streams.

HT/HTI’s continued digital influence is strongly linked to its internal doctrine. A key element is the concept of tabanni (Arabic for “adoption”), which requires members to fully accept the organisation’s ideas without questioning them. According to Heriansyah, this doctrinal practice is enforced through structured halaqah (Arabic for “study circles”) sessions, where questioning or disputing the materials is systematically prohibited. Such mechanisms consolidate internal ideological unity while shaping HTI’s external communication strategy.

Figure 4: A 2024 edition of the newsletter, affiliated with HTI, featuring a headline that frames the caliphate as both admirable and obligatory—reflecting the group’s continued ideological messaging post-proscription.

HTI relies on one-way content dissemination, such as e-books, doctrinal texts, and narrative videos, to reinforce beliefs rather than encourage dialogue. This fosters algorithmically reinforced echo chambers, where repeated exposure strengthens radical views and heightens the risk of self-radicalisation, especially among younger, digitally native users. HT and HTI also distribute these materials through dedicated websites and forums, enabling long-term ideological indoctrination and sustaining a transnational digital presence that resists state bans and offline crackdowns.

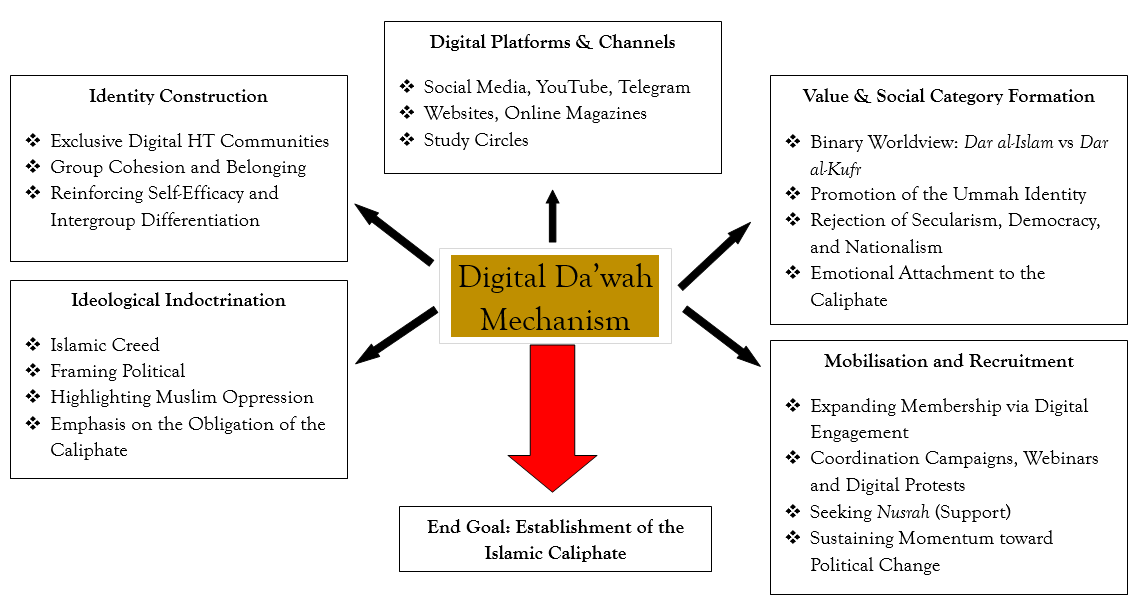

Figure 5: Hizb ut-Tahrir’s Digital Da’wah Mechanism: A structured process of ideological dissemination, identity construction, and mobilisation, aimed at establishing the Islamic Caliphate

From Ideology to Extremism: The Radicalisation Pathway

HT’s digital strategy is not solely aimed at disseminating ideas but also functions as a potential pathway towards violent extremism. While HT consistently positions itself as a non-violent movement, the group’s rigid ideological framework and binary worldview contribute to the gradual erosion of alternative perspectives, increasing susceptibility to radicalisation.

The concept of tabanni, which compels members to adopt the organisation’s ideas uncritically, is outlined explicitly in an internal doctrinal manual published by Hizb ut-Tahrir in 2000 through its affiliated press in London. This reinforces a cognitive environment where external viewpoints are delegitimised. Through repeated exposure to highly curated digital content, members are conditioned to internalise a dichotomous worldview—dividing the world into Dar al-Islam (the land of Islam) and Dar al-Kufr (the land of disbelief). This framing fosters not only a sense of victimhood but also the moral justification for rejecting existing socio-political orders, particularly democratic and secular systems.

Algorithmic amplification further exacerbates this process by increasing user exposure to ideologically consistent content. Social media algorithms promote material aligned with prior engagements, creating ideological echo chambers that normalise extreme views. HT-affiliated digital platforms regularly publish emotionally charged narratives linking Muslim suffering to the absence of Islamic governance. For example, an article written for the Central Media Office of Hizb ut-Tahrir, published in 2023, asserted that “It is only the Khilafah that will unify the Muslim Ummah, tear down the borders that divide the Muslims and mobilize the armies to liberate Al-Aqsa and the prisoners.” This framing positions the caliphate as the singular path to dignity, justice, and liberation, repeatedly reinforced through digital channels to emotionally mobilise audiences and validate anti-system sentiments.

In Indonesia, this ideological conditioning is evident in the case of Bahrun Naim, whose early exposure to HTI’s anti-democracy narratives preceded his involvement with ISIS. These narratives also brought him into contact with Munir Kartono, an individual whose radicalisation pathway illustrates the intersection between personal grievance and ideological indoctrination. Munir’s resentment stemmed from the economic hardship his family endured during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, which led to his mother becoming a factory worker and his father being perceived as irresponsible. His anger towards his family and the government eventually found ideological reinforcement through HTI’s narrative rejecting democratic systems.

This connection was further solidified when Munir and Bahrun Naim jointly engaged in online fundraising activities between 2010 and 2015, which they perceived as a form of jihad. Their collaboration culminated in Munir’s direct involvement in financing a suicide bombing at the Surakarta City Police Headquarters (Mapolresta Surakarta) in July 2016, resulting in the death of Police Brigadier Bambang Adi Cahyanto. This case exemplifies how HTI’s ideological narratives can act as an enabler, creating conditions conducive to further radicalisation and operational collaboration with violent extremist networks.

This pathway is not unique to Indonesia. As observed in Bangladesh, HT’s digital indoctrination similarly lays the foundation for extremist escalation, targeting educated youth through sophisticated messaging and gradual recruitment mechanisms. Financial and operational connections to transnational networks further enable HT to maintain this model across multiple regions.

Ultimately, while HT does not directly engage in acts of violence, its digital activities construct an ideological infrastructure that lowers the threshold for violence by cultivating a worldview in which confrontation with existing political systems is both inevitable and justified. This blurring of boundaries between non-violent extremism and violent radicalisation presents significant challenges for counter-terrorism efforts, particularly in the digital domain.

The Role of Tech Companies in Countering HT’s Digital Influence

HT’s strategic use of digital platforms presents significant challenges for technology companies. While avoiding explicit incitement to violence, HT persistently spreads anti-democratic, sectarian, and caliphate-centric narratives that fuel radicalisation. By exploiting moderation policies focused narrowly on violent extremism, HT’s content circulates widely across social media, websites, and encrypted channels.

The group’s use of “borderline content”—material that undermines democratic systems without directly promoting violence—places it within what the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) describes as the “lawful but awful” grey zone. Such narratives often evade moderation yet contribute to radicalisation pathways. Addressing this requires platforms to adopt more nuanced approaches that balance ideological risk with free speech protections.

Algorithm-driven systems further intensify the problem by amplifying emotionally charged content. HT’s narratives—focused on Muslim victimhood, oppression, and calls for Islamic unity—gain disproportionate visibility, reinforcing echo chambers and normalising extremist worldviews.

Tackling this challenge demands proactive strategies beyond content removal. Platforms must strengthen detection tools to identify ideological patterns linked to non-violent extremism and regularly audit algorithms that exacerbate exposure. Collaboration with governments, researchers, and civil society is essential to monitor HT’s evolving digital tactics and support credible counter-narratives that challenge its binary worldview.

Transparency around how borderline content is handled is equally vital, alongside monitoring HT’s use of digital fundraising and encrypted communications. Ultimately, confronting HT’s influence requires a systems-level response that disrupts its digital resilience and prevents the normalisation of extremist ideologies online.

Recommendations and Conclusion

To counter HT’s digital influence, technology companies need to prioritise the detection of non-violent extremist material that fosters sectarianism and undermines democratic principles. This issue became especially urgent in the lead-up to Indonesia’s 2024 elections, as HTI intensified its digital activity, using online platforms to delegitimise democratic participation and promote the caliphate as the only political alternative. This requires not only refining detection systems but also auditing algorithmic processes that may elevate such narratives. It also necessitates investment in human content moderation across diverse languages, as much of HT’s digital messaging operates in non-English contexts where automated systems often fall short.

HT’s transnational and decentralised structure underscores the importance of coordinated efforts between digital platforms, governments, and civil society organisations. For example, governments can provide regulatory frameworks and intelligence-sharing mechanisms, while civil society actors—including educators and grassroots organisations—can assist in identifying localised HT messaging and supporting targeted counter-narratives. Such collaboration ensures that interventions are contextually relevant, responsive to ideological nuances, and sustained beyond short-term content takedowns. Supporting locally grounded counter-narratives is equally critical to weaken HT’s ideological reach and reduce vulnerability to radicalisation.

Platforms must clarify their moderation policies on borderline content, particularly material that exploits the ‘lawful but awful’ space identified by GIFCT. Monitoring HT’s use of digital fundraising channels is also essential to weaken its operational resilience. Any response should strike a careful balance, limiting the reach of extremist narratives without undermining legitimate speech online.

Muhammad Makmun Rasyid is a Member of the Bureau of the Prevention of Extremism and Terrorism (BPET) at the Indonesian Council of Ulama (Majelis Ulama Indonesia) and serves on the Central Board of the Nahdlatul Ulama Scholars Association (ISNU). He has authored 15 books on Islam, including a counterterrorism trilogy in Bahasa Indonesia: Menangkal Bahaya Radikal-Terorisme: Upaya-Upaya Teologi dan Ideologi di Indonesia (Preventing the Dangers of Radical-Terrorism: Theological and Ideological Efforts in Indonesia, 2023), Api Pemikiran Abdullah Azzam: Dari Idealisme Bergeser ke Jihadisme (The Fire of Abdullah Azzam’s Thought: From Idealism to Jihadism, 2024), and Desentralisasi Terorisme (Decentralisation of Terrorism, 2025). He has also written a trilogy countering Hizb ut-Tahrir’s caliphate narrative, including HTI Gagal Paham Khilafah (HTI’s Misunderstanding of the Caliphate; 2016), Say No to Khilafah Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (2020), and Mabuk Khilafah: Para Tokoh di Balik Miskonsepsi Penafsiran Khilafah (Caliphate Intoxication: The Figures Behind the Misinterpretation of Khilafah; 2022)