Introduction

Research on extremism and counter-terrorism has long underscored the role of music in reinforcing far-right extremist ideologies and serving as a gateway to radicalisation. With the rise of generative AI music platforms like Udio and Suno AI, online extremists have gained new tools to create and amplify hateful music with unprecedented ease. Reporting by The Guardian this past summer revealed that Suno AI-generated songs circulated within Facebook groups may have contributed to a recent wave of far-right violence in the UK. Against this backdrop, this Insight examines how far-right communities have used AI platforms to reshape the landscape of online music propaganda. By analysing interactions on 4chan’s politically incorrect (/pol/) board, where users generate and spread hateful music through AI, this Insight investigates how the far-right exploits music platforms, the risks posed by it, and presents policy recommendations for tech companies to counter this harmful trend.

Background: Generative AI and Extremist Music

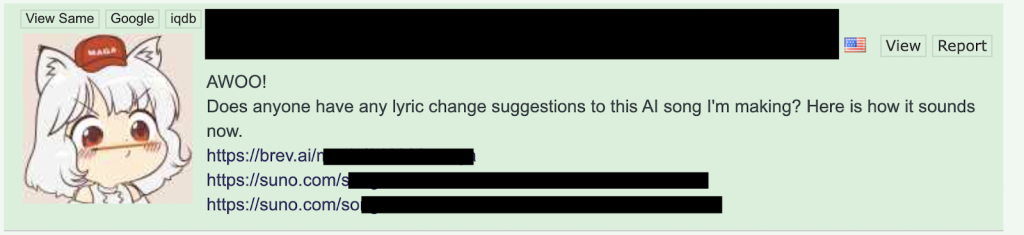

Following the release of generative AI music platforms in late 2023, 4chan’s politically incorrect board (/pol/) has emerged as a hub where users collaboratively produce hateful and propagandistic music. Thousands of posts have been dedicated to generating music propaganda on the website since the release of Suno AI, with further thousands of comments and music files. These threads openly encourage users to “weaponize and influence listeners” across the internet (see Figure 1). Some threads are ideologically focused, centring on themes such as “anti-Semitic music” or “racist music”, while others are dedicated to generating various forms of propaganda music, ranging from themes such as about the US elections to conspiracy theories. As one user reflects, the aim is to “make songs, make videos for them, upload to YouTube” and leverage platform algorithms to boost reach, thus increasing the potential for radicalising audiences across social media.

Figure 1. AI music thread encourages users to weaponise and influence listeners

Above all, 4chan AI music threads provide a space where ideologically aligned users experiment with tech platforms, post results, discuss challenges, receive feedback, and refine their creations while gradually increasing the quality of their hateful content. The threads contain detailed instructions that allow the most amateur user to produce high-quality music propaganda in a matter of minutes. When more expert help is needed, experienced users offer newcomers tailored guidance and tips on overcoming technical obstacles. For instance, in a 4chan thread, a novice user complained about the melody and rhythm of the song he tried to generate. Another user then advised: “Try pasting it into Chat GPT to help with lyrics or rhymes. Add labels like Verse 1 and Chorus. For Suno, the musical style prompt can be tricky; try adding ‘bluegrass banjo’ for more twang and less pop-country”. They then share links to their audio files, seeking feedback on results, often detailing the prompts and platforms used in the process. In this way, users are able to learn from each other and successfully generate hateful content by way of collective effort.

Figure 2. 4chan user asks for guidance to improve AI song

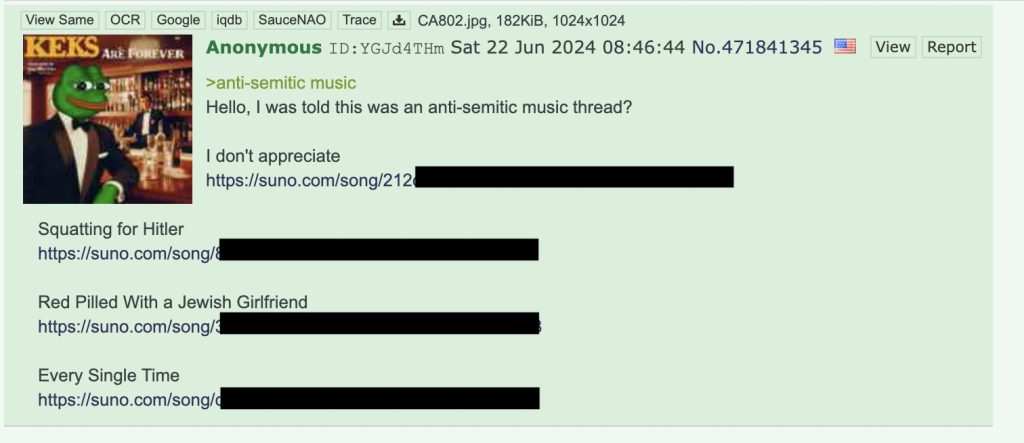

The themes of these hateful songs vary widely—from racist content targeting Black, Indian, and Haitian communities to antisemitic and even terrorist anthems inciting attacks on crowded spaces. Moreover, the content is generated and shared in several languages, including English, German, Portuguese, Arabic, and Dutch, indicating the global scope of this phenomenon. This is made possible by the vast array of languages supported by these platforms—Suno AI can generate songs in more than 50 languages. Users employ these platforms to infuse their harmful lyrical content into diverse musical styles, from rock and country to classical music. They frequently share multiple versions of the same hateful lyrics across various genres, aiming to reach and appeal to a wider audience. By categorising these tracks by genre (such as rock, country, pop, and classical), they can guide listeners toward their preferred style, ensuring the spread of hateful messages under a more familiar musical guise. This marks a concerning evolution as radicalising music content, once confined mostly to niche genres like far-right rock, can now be generated to emulate any music of any genre and style, including mainstream, which appeals to individuals across various regions and age groups. One user boasts that “in 10 seconds you can make music better than the shit on the radio”, highlighting the ease with which hateful and extremist messages can now be embedded in popular music formats.

Figure 3. 4chan user shares his AI songs in a 4chan antisemitic music thread

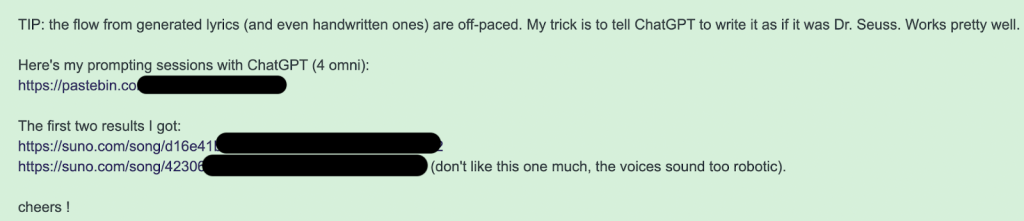

To achieve the highest quality of hateful audio content, users leverage not only AI music platforms but also text and image-generative tools. Specifically, by using text-based platforms like ChatGPT and Bing AI, they are able to generate hateful rhythmic and catchy lyrics. Few users write lyrics manually, as this demands more effort and often results in lower-quality content than AI-generated lyrics. As such, the emergence of AI platforms not only enhances the quality of propaganda produced by online extremist communities but also significantly reduces the effort required to create it, thus amplifying both the quality and quantity of audio propaganda circulating online.

Additionally, some users integrate imagery into their creative process, using visual content—such as memes and images shared within extremist circles—as inspiration for generating lyrics and songs through AI platforms. This approach leverages extensive collections of harmful imagery accumulated over time on forums like 4chan to refine and contextualize their messaging. These materials are stored in a public online database with over 170,000 files of hate images, which are widely shared on 4chan’s /pol/ board. The lyrics generated through these processes are subsequently processed through generative AI music tools, producing audio propaganda that resonates more effectively with their target audience.

Figure 4. 4chan user shares prompts and tips on generating hateful songs

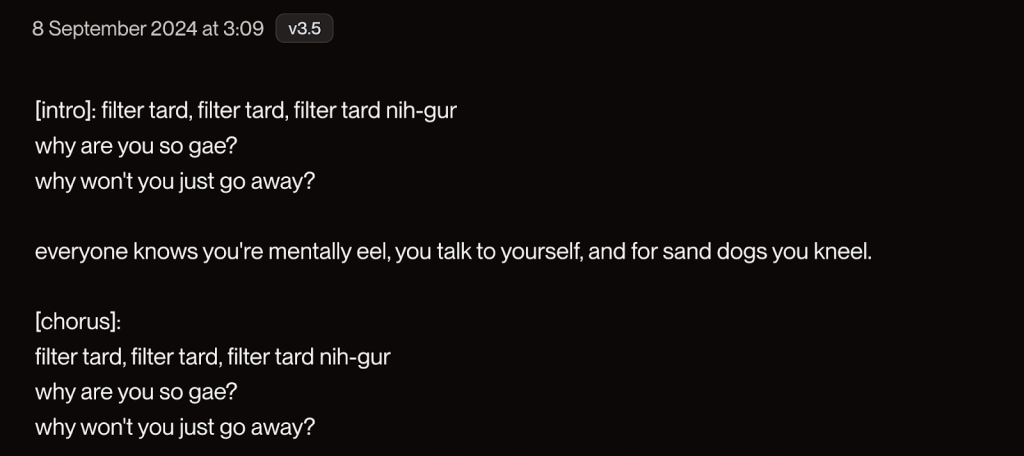

While the data shows that harmful users are successfully misusing AI to generate hateful music, their efforts do not go unchallenged, as most mainstream generative AI platforms’ Terms of Service (ToS) prohibit the generation and dissemination of hateful and terrorist content. Such policies are enforced via automated detection measures, which pose significant barriers to extremist users by blocking their attempts to generate harmful content and, upon multiple identified violations, banning their accounts. These measures, however, often prove insufficient, as users trick AI bots into violating platform policies by entering prompts that use phonetic tricks and coded language, a tactic known as “jailbreaking”. For phonetic jailbreaking, users prompt the AI to sing words like “nih-gur”, “gae”, and “nickers”, which sound like harmful slurs but evade automated detection. Coded language is another tactic, where users use seemingly neutral terms that contain hidden meanings in extremist circles—terms like “zogbots” for police officers, “octopus” for Jewish people, among others. This allows users to produce harmful songs while sidestepping detection filters and safety guards put in place by tech platforms.

Figure 5. Hateful song on Suno AI using phonetic and coded jailbreaking

Risks

The amplification of hateful songs by AI represents a dangerous trend and presents a number of societal risks. Generative AI platforms enable both novice and experienced users to produce high-quality songs that reinforce their radical ideological beliefs, deepening their engagement within extremist echo chambers. Research shows that hateful songs not only strengthen bonds and boost morale among those already committed to extremist ideologies but also serve as potent vehicles for spreading violent ideas and radicalising new individuals. By packaging radical beliefs into catchy, seemingly harmless songs, they are able to simplify and condense extremist tenets, making them more accessible and attractive to younger audiences by disguising the actual extremist content.

Figure 6. User claims to only listen to extremist AI-generated songs

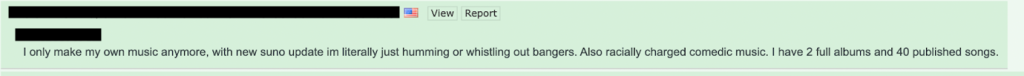

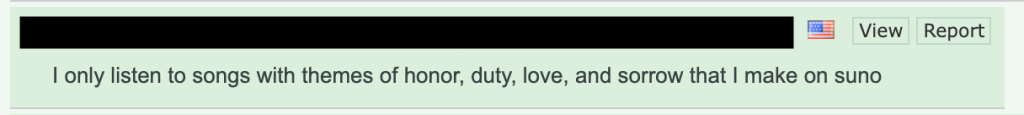

A concerning trend observed in the data collected is the emergence of echo chambers of hateful music, as many users report exclusively listening to extremist AI-generated music. For example, one user shares, “I only make my own music anymore; with new Suno updates, I’m literally just humming or whistling out bangers. Also racially charged comedic music. I have 2 full albums and 40 published songs” (see figure 6). Similarly, another user states, “I only listen to songs with themes of honor, duty, love, and sorrow that I make on Suno” (see figure 7). This practice allows radicalised individuals to immerse themselves further within their extremist and often violent ideologies, a level of isolation previously difficult to achieve through music alone. In addition, considering the violent nature of some of the songs analysed, this practice poses the potential for offline violence. One of the songs analysed explicitly calls out lonely suicidal listeners to commit terror attacks in locations such as “a hotel lobby, a packed cafe, or a grocery shop at the end of the day”. Christchurch attacker, Brenton Tarrant, also shared similar thoughts on 4chan prior to his attack, discussing the need to attack minorities in locations of “significance”, including places of worship, which shows that such narratives on 4chan have a precedent for significant offline violent behaviour.

Figure 7. User claims to only listen to extremist AI-generated songs

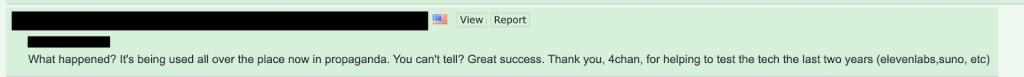

“Strategic mainstreaming”, a tactic used by extremists to influence public discourse by deliberately exposing broader audiences to hate content, is another concern. 4chan is seen by many as a starting platform to learn how to weaponise AI, with the intent to later expand their reach to other websites. In several discussions analysed, users celebrate when they see their content spreading across mainstream social media, with one user noting, “[our content] is being used all over the place now in propaganda […]. Thank you, 4chan, for helping to test the tech over the last two years (elevenlabs, Suno, etc.)” (see figure 8). By moving to platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Spotify, hateful content gains wider visibility, with an increased risk of radicalising individuals who encounter it—especially youth and young adults, whom studies show to be more vulnerable to radicalisation through music.

Figure 8. User celebrates AI-generated propaganda spreading through the internet and 4chan’s role as a facilitator

The risks of mainstreaming extremist and violent ideologies are further augmented by user’s attempts to exploit social media platforms’ algorithms to artificially boost the reach of their content. For instance, one user can be seen suggesting that like-minded individuals should interact as much as possible with the content shared on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube to create an algorithmic boost, possibly having the “potential to get in front of 50,000+ people”. The user adds, “the greatest way to get exposure is if you’re blessed with an outrage response video from some fat retarted [sic.] idiot on TikTok with a decent following”. This is not an isolated case, as shown by a recent study by the University of Southern California (USC) , which found evidence that far-right accounts on X and Telegram are collectively interacting with extremist narratives to artificially popularise them by inducing platforms’ algorithms to distribute the content more widely.

Conclusion

This Insight highlights how 4chan users are weaponising generative AI music platforms by fostering an extremist online community where they can freely learn to manipulate these tools to generate and disseminate hateful songs. Although the ToS of tech platforms prohibit the creation and distribution of hateful and violent content, users have developed ways to bypass safety features that enforce platforms’ ToS, often by playing with phonetics or using coded language in the lyrics, a tactic known as “jailbreaking”. Once successfully generated, hateful songs are often uploaded onto mainstream platforms in an attempt to increase visibility, radicalise individuals exposed to it, and mainstream extremist views.

Recommendations to tech platforms:

- Enhance Automated Detection Mechanisms: Invest in researching coded language and phonetic “jailbreaking” by establishing dedicated red teams to identify and anticipate the phonetic workarounds users might employ. This proactive approach allows tech companies to stay ahead in detecting and deterring the generation of harmful content. Additionally, invest in research that examines how users weaponise these platforms, allowing for the collection and analysis of prompts used to bypass safeguards.

- Promote Cross-Platform Collaboration: Evidence gathered for this Insight shows that users often utilise multiple platforms before successfully generating extremist content. Greater collaboration and knowledge-sharing across tech platforms can foster a resilient community equipped to tackle jailbreak and misuse issues more holistically.

- Implement Identity Verification Measures: Findings from a recent report by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) indicate that eliminating anonymity on generative AI platforms through identity verification may help disrupt extremist activities. This measure would enable tech platforms to identify individuals producing hateful content and facilitate law enforcement agencies in holding users accountable for generating and disseminating hate and terrorist content.

Heron Lopes is a Research Assistant at Leiden University’s Institute of Political Science and the Uppsala Conflict Data Programme (UCDP), where he conducts Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) research on political violence and insurgency in Southern Africa and Latin America. He has also worked for the Current and Emerging Threats Programme of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), where he conducted research on the nexus between Artificial Intelligence (AI) and terrorism. He holds an MSc in Political Science from Leiden University and an LLM in “Law and Politics of International Security” from The Vrije Universiteit (VU) Amsterdam.