Introduction

There are myriad ways in which women engage in extremist ideologies, including Islamist extremism and fundamentalism. Across regions, entrenched gendered dynamics, societal hierarchies and prescribed social roles influence women’s decisions to engage with extremist ideologies. These structures, or ‘gender orders’, contribute to shaping the social construction of femininity, sometimes reinforcing narratives that link extremist ideologies with gender-based violence targeting individuals or groups based on their gender identity.

In our increasingly interconnected world, gendered and extremist narratives are spread through various social media platforms. Previous research on violent extremism focusing on Islamist radicalisation online focused on Telegram, Facebook and YouTube as the main virtual spaces where radicalisation and recruitment occur. Yet, the fast-paced online environment propelled the emergence of platforms like Instagram and TikTok. These platforms have been used to distribute radical or extremist content to young women vulnerable to radicalisation. Looking at the response to the Israel/Palestine conflict among Indonesian youth as a case study, this Insight aims to explore how constructions of femininity and piety on Instagram and TikTok contribute to the propagation of extremist narratives that endorse gender-based violence.

Instagram and TikTok in Indonesia

Instagram and TikTok have gained remarkable popularity among young people in recent years. Instagram has over a billion monthly users, with more than 61% aged between 18 and 34. Meanwhile, 34% of TikTok’s 1.7 billion users, are aged 18 and 34. In Indonesia, both platforms have over 110 million users each and are notably most popular among young women. Specifically, 55.4% of Indonesian Instagram users and more than 70% of TikTok users are women. These statistics underscore the significant influence of both platforms among young women in Indonesia.

Gender-based Violence Narratives in Instagram: The Case of Oka Setiana Dewi

Indonesia has a long history of ‘gender order’ condoned by the state, society and religion. At the forefront of the contemporary Indonesian gender order is the notion of the ‘ideal’ Indonesian Muslim woman. The state historically utilised gender politics to reinforce women’s domestic roles during the Indonesian authoritarian period from 1965-1998. During the democratisation period starting in 1998, the reinforcement of conservative and Salafist ideologies in Indonesia intensified the existing gender order. This escalation became more pronounced with the widespread adoption of fundamental Islamist values, shifting the definition of the ideal Indonesian woman to the ideal Indonesian Muslim woman.

The use of gendered narratives to radicalise women is one of the clearest links between gender-based violence and extremism. One dimension linking GBV to violent extremism involves propagating values that subjugate women in society, emphasising men’s control over their bodies, and promoting their traditionally feminine roles as mothers and housewives. In Indonesia, this narrative of subjugation is a tangible form of gender-based violence reinforced by societal gender norms that stress women’s femininity and piety.

On Instagram, accounts endorsing jihadi ideology often also promote mainstream conservative religious views that align with gendered expectations in Indonesia. These accounts advocate for women to be fully covered in niqab, and imply that those showing their faces are sexually promiscuous. While these religious narratives can inform online gender-based violence, they are often endorsed by women themselves, including the prominent female influencer Oki Setiana Dewi, a fundamentalist and anti-feminist influencer in Indonesia. While Oki is not a jihadist supporter, her views on gender and women’s piety reflect those of extremist groups in Indonesia, such as the Indonesian ISIS-affiliated groups Jemaah Islamiyah and Darul Islam.

As an actress, author, activist and powerful female cleric, Oki Setiana Dewi has amassed over 21 million followers on Instagram. However, some of Oki’s Instagram posts were criticised for normalising domestic violence. In a post that went viral in early 2022, Oki condoned domestic violence and claimed that women who speak up against their husbands are a disgrace to their households. Other Instagram posts from Oki have stoked widespread hatred and fear of LGBTQ+ people on behalf of Islam and advocated for restricting women’s roles in the domestic sphere to adhere to conservative norms to embody the ideal Muslim woman. This post was captioned ‘A Noble Muslimah Stays Home’, demonstrating the power of female antifeminist influencers who amplify antifeminist messages in ways that make other women listen and adapt their behaviour.

Fig. 1: [translation] “A Noble Muslimah Stays Home”

Fig. 2: [translation] “LGBTQ+ people are damned”

Gender Order and the Palestinian Cause: The Construction of Femininity in TikTok

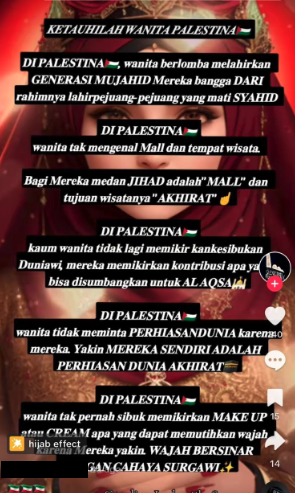

In Indonesia, a nation with the world’s largest Muslim population and a commitment to democratic values, the Palestinian cause has garnered significant traction, especially on TikTok. However, some individuals supporting religious fundamentalist ideologies have sought to draw parallels between the construction of ideal Indonesian femininity and the Palestinian struggle. In some TikTok posts, a comparison is made between Indonesian and Palestinian women, in which the latter is seen as not only physically beautiful but also deeply pious, referred to as ‘bidadari surga‘ or ‘heaven’s angels’ (Fig. 3). In another post, a comparison is drawn to shame Indonesian women for their perceived preoccupation with unimportant worldly matters like shopping, makeup, skincare, and jewellery, while Palestinian women are fighting for Islam by giving birth to mujahedeen and waging jihad (Fig. 4). Another post suggests that while women in Palestine are willing to endure hardship to preserve their right to wear hijab, it is deemed shameful that Indonesian women might choose to unveil for the sake of showcasing their beauty. Both images illustrate the expectations of Indonesian women by presenting the imageries of seemingly picture-perfect Palestinian women.

Fig. 3: Palestinian women are ‘Heaven’s Angels’

Fig. 4: Indonesian women’s worldly matters

These posts reveal attempts by antifeminists and fundamentalists to manipulate and disempower women by exploiting the highly nuanced Palestinian cause to instil feelings of shame and guilt among those who may not conform to idealised expectations of being a Muslim woman. Essentially, proponents of religious fundamentalist and extremist ideologies employ the trope of the Palestinian woman as a symbolic figure embodying traditional gender values, using gender-specific narratives to attract and recruit young women and girls on online platforms. The worrisome aspect is that these narratives often neglect the complexities of the actual conflict, instead arbitrarily linking it to demands for women to adhere to domestic roles under the guise of Islamic values. This poses a risk as young women may readily associate their inability to conform to these role models with the failure to meet expectations of being the ideal Muslimah.

Conclusion

Religious practice is integral to achieving socio-religious status- a notable aspiration for many Indonesian women today. In pursuing pious femininity, they seek recognition as physically beautiful, religious, obedient, and empowered; both Instagram and TikTok provide women with platforms to showcase their socio-religious status and validate their piety. Unfortunately, these are also the spaces where online narratives endorsing offline gender-based violence can proliferate, for example, under the guise of unrelated religious causes such as the Palestinian conflict.

Therefore, regulators must pay more attention to the gendered construction of women’s piety that may be utilised by extremist, fundamentalist and antifeminist groups to spread radical beliefs aiming at supporting gender-based violence. It can be done by encouraging multistakeholder collaboration, consisting of government, civil society and tech companies like TikTok and Instagram. Government-backed digital knowledge platforms like K-HUB aimed at preventing violent extremism (PVE) and civil society organisations like She Builds Peace fostering young women’s political agency could initiate contact with TikTok and Instagram to promote counternarratives addressing this issue.