Introduction

Ireland has seen limited instances of far-right and xenophobic nationalism, as left-wing political movements predominantly shape the nationalist landscape. Nonetheless, a far-right milieu has emerged in recent years. The movement, comprised of social media agitators, groups, and political parties, challenges the conventional definition of Irish nationalism, often labelling themselves as the true torchbearers of Ireland’s nationalist heroes.

This Insight will summarise an analysis of 45 Irish far-right channels on Telegram, exploring their articulation of an alternative Irish nationalist identity that aligns with their ideology. They construct this identity in two ways. Firstly, they undermine the legitimacy of the currently dominant left-wing nationalists. Secondly, they construct a form of ‘counter-memory’, reinterpreting history to challenge hegemonic narratives surrounding Irish nationalism and republicanism. In doing so, they promote their exclusionary perspective and present themselves as an Irish nationalist vanguard with historical roots.

Political Context: Leftist Irish Nationalism and Sinn Féin

The tradition of Irish nationalism departs from the exclusionary nationalisms seen elsewhere across Europe. Formed in the context of the struggle for independence from Britain, nationalist ideology focused on the plight of Catholics within Ireland and resisting British colonial rule. Over the last century, Irish republicanism has been influenced by both Catholic conservatism and a strong leftist strain, with the latter becoming more influential in the 1970s.

The absence of a significant radical right political party in Ireland has been attributed to the presence of ‘Sinn Féin’, a leftist Irish republican party that advocates for a united Ireland. Although it has progressive and social justice policies, Sinn Féin occupies the space in Ireland that radical right parties typically do in other countries. However, as Sinn Féin becomes more mainstream, a space has emerged where far-right anti-establishment alternatives could flourish.

Undermining Rival Nationalists

The far-right views Sinn Féin as a contender to be challenged for the space of pioneering Irish nationalism. Indeed, Sinn Féin is the most frequently mentioned party on far-right Telegram channels, surpassing even those in the governing coalition. Attacks on Sinn Féin centre around three main aspects: their left-wing politics, pro-immigration stance, and accusations of being under British control. These critiques seek to portray Sinn Féin as a weak and ineffective force for Irish nationalism.

On Telegram, the far-right accuses Sinn Féin of having turned ‘woke’ and co-opting “Irish Patriotism to divert it towards Marxism”. They are criticised for being excessively focused on and “absorbed by globohomo” a blend of ‘globalist’ and ‘homosexual’, referring to a form of global cultural homogenisation. Their support for minorities and social justice issues is framed as having deflected their attention away from pursuing the ‘Irish National Idea’, an idea that places the Irish homogenous nation above all other considerations. More broadly, leftist belief systems in general are blamed for having “watered down” Irish republicanism throughout history, building a narrative that positions the far-right as the only viable alternative.

The party are labelled the “biggest advocates of open border style mass immigration” and “traitors” to the Irish working class – a voter base they have traditionally depended on, who are worst affected by an ongoing housing crisis. Parody slogans like “Brits out, Africans in” ridicule Sinn Féin and undermine their reputation as the leading force of Irish nationalism and those most concerned with protecting Ireland’s right to sovereignty, while simultaneously associating them with grievances surrounding immigration and housing shortages.

Lastly, Sinn Féin is accused of being influenced by British control and in “collusion” with Westminster, being disparagingly labelled by activists on Telegram as “Sinn Féin/MI5” and “MI5 controlled colonial subjects”. These allegations further undermine Sinn Féin’s nationalist credentials and portray them as incapable of Irish reunification, painting the group’s leftward shift as a British plot to weaken Irish nationalism. Additional conspiracies suggest that MI5 has infiltrated media and government institutions to undermine the Irish state, seeking to oversee the globalist takeover of Ireland. These claims include assertions of funding think tank reports and appointing an MI5 agent as Commissioner of the Garda Síochána (Irish police). Outreach from British far-right figures tied to Ulster Loyalism is also seen by some as an MI5 psychological operation to discredit and divide Irish activists.

Decontextualising Irish Nationalism

The far-right strategically positions itself as a ‘true’ Irish nationalist movement by contesting the historical legacy of Irish nationalism and constructing a counter-memory. On Telegram, this manifests in two ways. Firstly, they challenge hegemonic renditions of the past by showcasing an alternative lineage of Irish nationalists through which they can impart their own politics. Secondly, they decontextualise quotes from leading Irish nationalists and republicans, repurposing their words to serve their far-right nationalist agenda. In doing so, they draw parallels between resisting British colonialism and perceived globalist interference in Ireland.

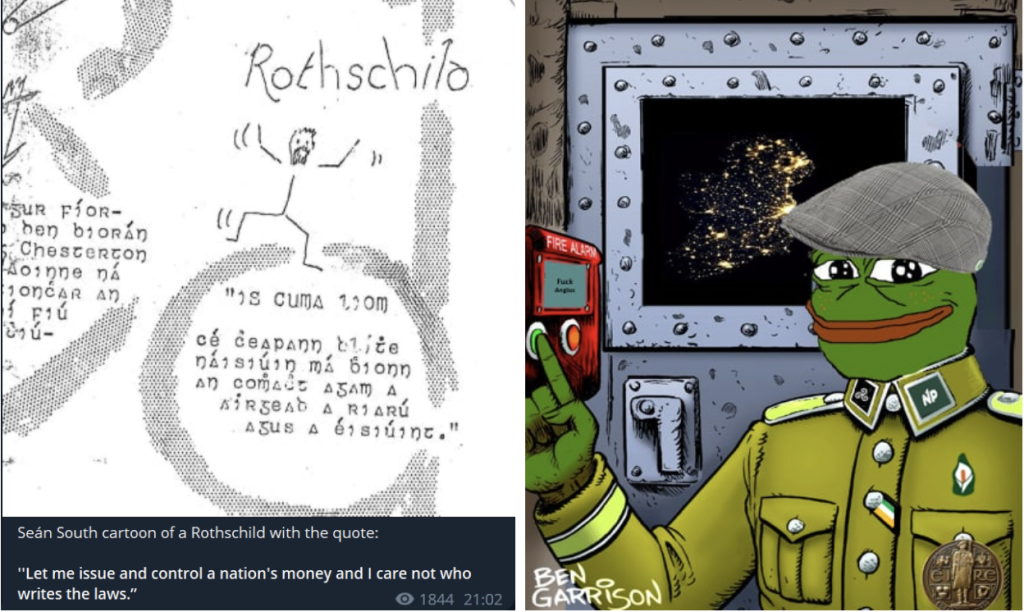

Irish far-right channels commemorate Irish nationalists and republicans with far-right links or fascist tendencies to challenge the notion of Irish nationalism as an inherently leftist movement. These groups and individuals allow them to point to a bedrock from which they can develop their own traditions. Those mentioned include Sean Russell, a member of the Irish Republican Army who collaborated with Nazi Germany during the Second World War, and IRA martyr Sean South, a Catholic zealot and anti-Semite killed during an attack on a Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks in 1957 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Left: A post highlighting the antisemitism of Seán South, featuring excerpts from his notebooks. Posts such as these serve to highlight a legacy of fascist thought within the cause of Irish nationalism. Right: A meme parodying claims the Irish kept their lights on to help the Luftwaffe bomb England. The Pepe wears a mixture of Irish republican and far-right symbols

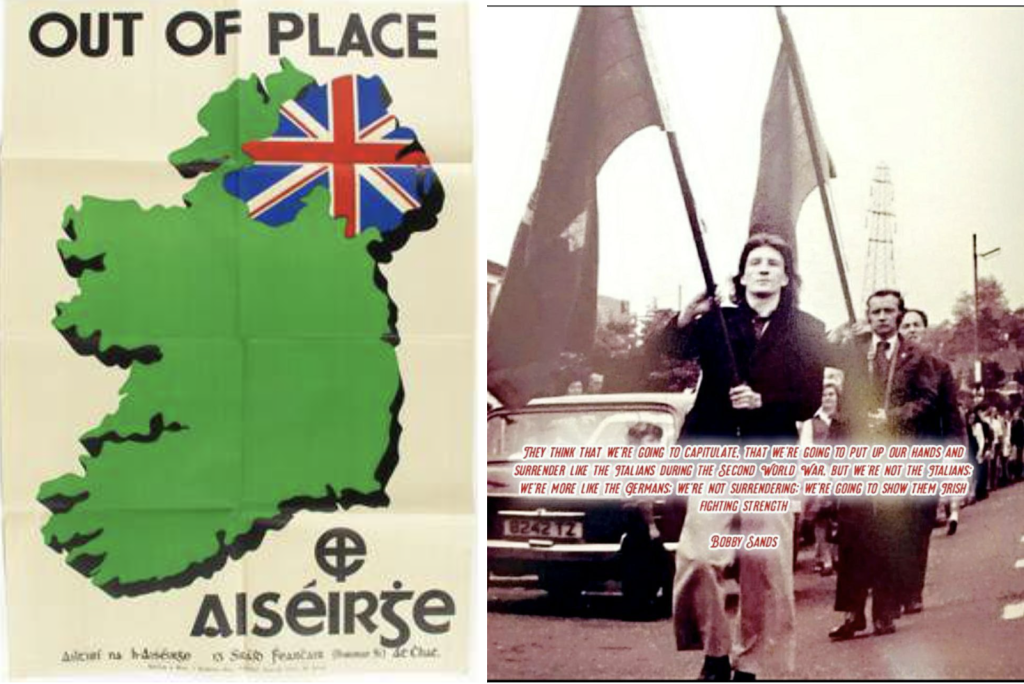

Individuals with beliefs more in line with the contemporary far-right are blended with the legacy of more mainstream and traditional Irish revolutionary heroes. For example, one channel affiliated with the far-right National Party honours the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising and republican hunger striker Bobby Sands (Fig. 3). Simultaneously, they celebrate groups like Ailtiri na hAiséirghe (Architects of the Resurrection), an Irish pro-Axis fascist party, and the 1930s pro-Franco anti-communist Blueshirts paramilitary organisation. In doing so, they aim to equalise their legacies and blur the lines between hegemonic historical memory and strands of nationalism more congruent with far-right ideology.

Fig. 2: Left: An Ailtiri na hAiséirghe anti-partition poster shared on Telegram. Right: A quote from hunger striker Bobby Sands comparing the Irish fighting spirit to that of Germany in the Second World War.

The second aspect of this counter-memory construction involves the sharing of commemorative posts containing selective quotations from Irish republicans and nationalists. Statements relating to the preservation of Gaelic culture or the ‘Irish race’, originally addressing British colonialism, are prevalent across Telegram. These quotes are separated from their original historical context and used to support and justify far-right agendas and nativism.

For example, the leftist legacy of James Connolly, a socialist, trade union leader and a hugely important figure to the modern Irish left who was executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising, is contested with selectively shared quotes used to distance him from contemporary leftist positions, including his comments on social agendas such as LGBT rights or on mass migration.

In one instance, a post on the Telegram channel of a far-right nationalist group co-opts Connolly’s words referencing the struggle for Irish independence, to oppose foreign labour in Ireland today, stating: “Like James Connolly we oppose both the ‘irresistible force of capitalism that crushes all national and racial characteristics’ and so too do we oppose the ‘obedient mercenaries of Capital’”. The ideological appropriation of this quote hinges on Connolly’s use of the term ‘racial characteristics’, language typical of its time, which enables the distortion of his views to align with their ideology.

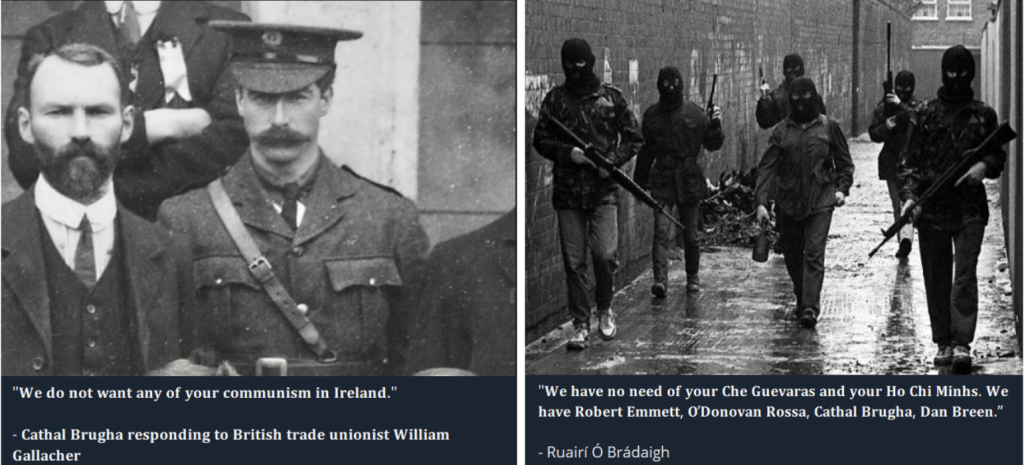

Fig. 3: A regular theme of quotation posts focuses on distancing historical Irish nationalists and republicans from the contemporary left

A further example features Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, the former Chief of Staff of the IRA and leader of Sinn Féin. In one post, a photograph of Ó Brádaigh is accompanied by the line: “We want Ireland to belong to the Irish, to the people of Ireland; and that embraces all aspects of Irish life; including the wealth of Ireland and her culture”. This statement relates to opposing British rule, but within the context of the far-right ecosystem in which it is circulated, the quote is repurposed for a nativist agenda and to connect the far-right’s ideology to Irish revolutionary tradition. Another Ó Brádaigh post reads: “We have no need of your Che Guevaras and your Ho Chi Minhs. We have Robert Emmett, O’Donovan Rossa, Cathal Brugha, Dan Breen.” In this case, his rejection of international influence on Irish nationalism is warped to contribute to developing a far-right vision of Irish republicanism characterised by disavowing links to revolutionary leftism. Manipulating the legacies of these influential historical figures lends legitimacy to far-right ideologies.

Conclusion

This Insight identifies two approaches to constructing a far-right Irish nationalist identity within far-right groups on Telegram. Firstly, the currently dominant left-wing brand of Irish nationalism, which does not focus on anti-immigration, is delegitimised as unviable for preserving the sovereignty of Ireland. This theme mostly focuses on Sinn Féin, whose left-wing political views are used to portray them as weak, distracted and unable to protect the cultural and political identity of the nation.

Secondly, the Irish far-right rewrites hegemonic historical narratives of Irish nationalism through a process of counter-memory, appropriating the legacy of revered historical figures to gain legitimacy and present the far-right as a vanguard of Irish nationalism with historical roots.

It has been argued that the Irish far-right has failed to make breakthroughs because their political discourse and narratives were adopted from overseas and a uniquely Irish manifestation had yet to develop. This analysis of far-right discourse on Telegram reveals an ongoing attempt to formulate a unique brand of far-right Irish nationalism. Given the profound integration of Irish nationalism within Irish society and cultural identity, it is crucial to monitor how the far-right use and manipulate historical nationalist symbols and figures to serve their agenda.