In 2025, Pakistani security forces witnessed at least 405 quadcopter attacks by Islamists Tehreek-e-Taliban (TTP) and Ittehad-ul-Mujahideen (IMP) in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. Concurrently, TTP and IMP acquired anti-drone technology to ward off aerial attacks and disrupt the surveillance and monitoring capabilities of police and security forces. This could signify a potential arms race between militant groups to accelerate drone attacks and adopt technologies to evade counter-terrorism efforts.

Attacks by TTP and IMP are aimed at achieving strategic leverage in geographic areas that are otherwise beyond their usual physical reach. The convergence of defensive measures (anti-drone systems) with offensive tactics (drone attacks) reflects a significant shift in the militant operational landscape.

While displaying their anti-drone capabilities, these groups have simultaneously launched coordinated drone attacks, an emerging tactic that marks a new phase in militant warfare in Pakistan. Such coordination demonstrates increasing sophistication in planning, communication, and technological adaptation. This trend highlights not only the normalisation of drone-based technologies in the region but also the militants’ parallel emphasis on protecting their operational spaces through disrupting surveillance measures.

This Insight aims to examine coordinated drone attacks in Pakistan with a specific focus on the anti-drone capabilities of militant groups, assessing their strategic intent and technological evolution. The analysis pays particular attention to exploring coordinated drone attacks and their security implications in the region.

Learning From the Battlefield

Pakistan recorded 5397 terrorism-related incidents in 2025, with jihadist groups increasingly adopting new tactics. In particular, the acquisition and adaptation of drone technologies, often sourced from active conflict zones, have raised serious concerns among Pakistani security forces. In recent years, there have been several cases in which militants claimed to have acquired equipment from downed security-force drones (Figure 1). Further, the use of thermal-imaging weapons to shoot down these drones has made it easier for militants to capture and exploit this technology.

Figure 1: IMP statement indicating militants claim to acquire drones in the Orakzai Agency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

In its 2025 annual report, TTP, while asserting its familiarity with and adaptability to modern technologies on both the media and battlefield fronts, released an AI-generated video showing the destruction of military and state infrastructure. In the background, the report statistics suggested that the group had captured at least 10 drones used by security forces during various counter-terrorism operations. Subsequently, the Baloch armed groups, Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), also claimed to have downed 10 drones in different clashes in the Balochistan province as well.

In another instance, militants claimed to have downed a DJI matric 300 RTK drone, and reportedly gained access to the data stored in this drone. This is a high-performance industrial drone equipped with an advanced flight control system, a six-directional sensing and positioning system, and equipped with a first-person view (FPV) camera. For militants to have acquired it marks a concerning advance in militant technological warfare. This drone technology enhances operational safety and reliability, and it also supports an optional obstacle-detection module that can be mounted on the aircraft’s top. This UAV offers a range of intelligent flight features equipped with AI spotting to capture guided instruction, AI spot-check, pinpoint capabilities for location sharing, and a substantial payload.

Drone Jammers Are Changing the Game

In the KP province of Pakistan, counter-terrorism forces thwarted at least 375 drone attacks across the three districts of Banu, Bajaur, and North and South Waziristan, highlighting a shift in militant strategy from conventional warfare to a more technology-driven conflict, targeting from the ground to the sky. As a countermeasure, Pakistani authorities have adopted additional tactics, including the deployment of anti-drone technologies and drone nets, to protect security forces along the provincial border between Punjab and KP. At the same time, security forces are using the sky as an advantage over the mountainous and urban terrain, tracking and surveilling militants’ routes, making it increasingly difficult for them to operate independently under the threat of aerial oversight. In response to the increasing number of drone-based attacks, the KP police have announced Pakistan’s first anti-drone unit to equip authorities with the skills to counter such threats. For this purpose, a team of IT experts will be overseeing the plan, and a specialised course to respond to drone attacks has been launched accordingly.

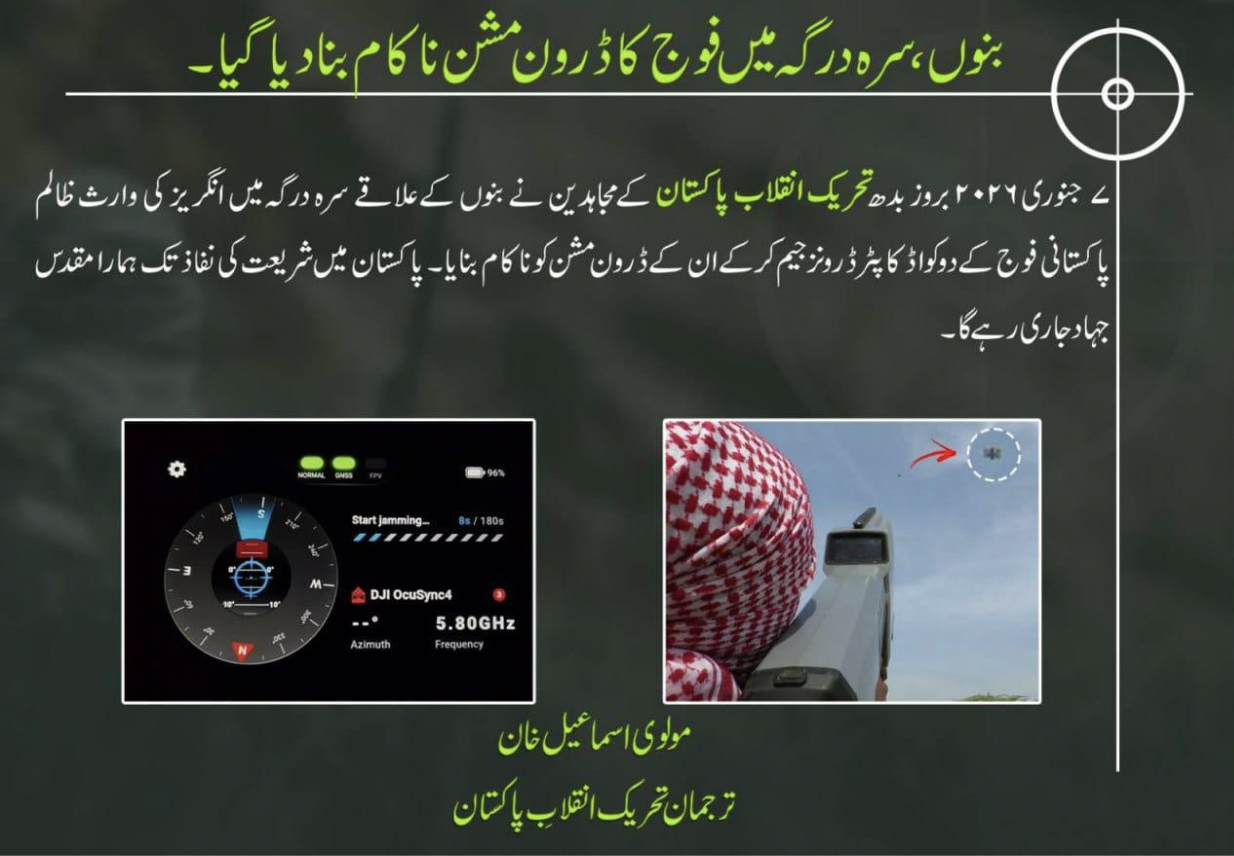

Figure 2: IMP propaganda illustrating how its fighters are downing a quadcopter in the Bannu district using a drone jammer.

In response, militants have also started adopting drone jammers and anti-drone technology to try to maintain parity with the security forces in the militant-hit regions of Pakistan, particularly, KP province.

Media reports indicate that Safrah anti-drone guns – locally produced by Pakistan’s National Electronic Complex (NECP) and designed to counter illicit drone incursions – have been captured and acquired by jihadist groups on the battlefield. This development makes counterterrorism efforts more difficult by complicating the assessment of these groups’ adaptability patterns. In addition, TTP has announced a new aerial unit to modernise its guerrilla tactics alongside traditional counterterrorism measures.

Coordinated Drone Attacks

Militant actors in KP province are not only seeking ways to counter jammer technologies but are also attempting to sabotage their effectiveness. Following the deployment of anti-drone guns by state authorities, militants quickly developed new strategies within months to disrupt these counter-drone efforts, while simultaneously carrying out coordinated drone attacks in KP’s Dera Ismail Khan and Bannu districts.

Technological adaptations by militants have also reduced the number of other types of attacks, such as improvised explosive device (IED) and vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attacks in the province. On the other hand, a surge in aerial attacks indicates a modern guerrilla fight in the sky and on the ground as well.

Similarly, coordinated drone attacks have forced authorities to revisit their policies and increase efforts and economic costs to bring down clusters of drones by deploying more than one anti-drone gun at the offices of law enforcement agencies and peace committees, which militants often allege to be collaborators. Militants, through surveillance and monitoring of vulnerabilities in military installations, have also frequently triggered ground battles in KP province.

To Rule the Sky

As militant groups seek to increase their ability to disrupt state authorities from the air, they have increasingly turned to technology-driven competition with one another. This has led to greater reliance on commercial quadcopters and more advanced platforms, including FPV drones and satellite-based mapping tools. The IMP, which openly claimed responsibility for quadcopter attacks in KP province, compelled TTP to maintain its perceived superiority over rival groups.

Figure 3: Screengrab of TTP militants dropping a bomb from the sky on a vehicle of security forces.

It is further observed that TTP was initially reluctant to reveal its drone capabilities in order to maintain a psychological advantage over security forces. However, the public claims by IMP pressured the group to begin openly claiming quadcopter attacks. Moreover, competition with other militant groups, combined with evolving countermeasures by security forces, has further accelerated self-reported drone attacks. Similarly, in an effort to maintain strategic leverage, militants used drones to pursue a security forces vehicle in Bannu district and recorded footage of an aerial munition drop, demonstrating an attempt to sustain an operational edge over security forces across both airspace and ground routes.

Conclusion

The growing race to acquire the latest technologies among the militant factions, including the use of quadcopter drones, is simultaneously reshaping the future landscape of security measures in Pakistan. At the same time, militants’ modification of drone technology—particularly commercially available drones—has made it increasingly difficult to assess technological dynamics. It signals a departure from traditional guerrilla tactics, a rise in attack frequency and enhanced militant capabilities to strike high-value targets deep inside military installations.

Moreover, the acquisition of anti-drone technology has provided some leverage to security forces; however, its proliferation into militant hands highlights an ongoing technological battle for control over modern battlefield tools. This process allows militants to gain operational experience with these technologies, empowering them to better shield themselves from counterterrorism efforts. Coordinated attacks as a tactic further indicate militants’ rapid learning curve and adaptability in disrupting security measures by engaging forces simultaneously on both ground and aerial fronts. It is not a mere evolution of the weaponry system, but a transformation in operational doctrine as it is a battle for the sky, synchronised with ground assaults and strategic maturity.

Similarly, technological competition between groups such as the IMP and the TTP could further accelerate the adoption of militant technology in KP province. At the same time, the potential expansion of quadcopter drone technology among Baloch armed groups could further escalate the insurgency landscape in Balochistan, particularly in urban centres, by enabling operations aimed at blocking major supply routes and maintaining control of highways for extended periods. As of now, Baloch armed groups have lacked the capability to monitor the aerial space and counter security force patrols effectively. However, these groups have already begun deploying drone technology for propaganda purposes, as well as for limited surveillance during attacks on security checkposts, using drones to assess the presence of personnel inside defensive trenches.

–

Imtiaz Baloch is a journalist and researcher with a particular interest in political development and security in Pakistan’s Balochistan and Iran’s Sistan-va-Baluchestan provinces. He works as a Researcher at the Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS), Islamabad. He tweets at @ImtiazBaluch.

Esham Farooq is an MPhil Scholar at the School of Politics and International Relations, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. She is also working as a Research Officer at the Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS).

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.