This Insight was published as part of GIFCT’s Working Group on Addressing Youth Radicalization and Mobilization. GIFCT Working Groups bring together experts from diverse stakeholder groups, geographies and disciplines to offer advice in specific thematic areas and deliver on targeted, substantive projects.

In the last decade, Latin America has witnessed a profound paradigm shift in youth radicalisation linked to ISIS ideology. In 2015, Operation Hashtag, conducted shortly before the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, revealed the functioning of the first active jihadist cell in the region. The group was composed of young Brazilian adults who used Facebook, Telegram, and WhatsApp to spread ISIS propaganda and plan attacks in São Paulo and Rio during the international sporting event. However, the investigation had shown that behind the virtual dimension, a real network also existed: some of the members knew each other personally. Ten years later, the rise of the decentralised web (DWeb) has transformed the digital landscape, dispersing control among users and making online moderation almost exceedingly difficult. This shift has widened global connections, enabling violent extremists in Latin America to engage directly with radicalisers abroad. At the same time, youth are increasingly involved in such activities, raising concerns about the social factors driving this change, including poverty, inequality, and educational deprivation that make minors particularly vulnerable to extremist propaganda.

This Insight examines the radicalisation transformation that has occurred, focusing particularly on Brazil, and shows how the decentralised web is cultivating an online ecosystem that inspires new lone actors in Latin America.

The Transformation of Online Radicalisation

In 2015, Operation Hashtag first shed light on ISIS’s penetration into Latin America. Just days before the Rio Olympics, Brazilian police arrested a network of young nationals across various states who were planning to carry out attacks during the event. According to court documents, they all shared low socio-economic status and poor education. Two of them had met in Egypt, where they had been invited to study Arabic, before later attending radical preaching sessions in São Paulo led by foreign clerics. Social media served to expand the network and amplify the group’s radical message, reaching other young Brazilians who ultimately did not participate in the plot. In a closed online group, members circulated posts advocating the introduction of Islamic sharia law in Brazil. They also exchanged information on how to pledge bayat, or allegiance, to the Islamic State. WhatsApp and Telegram groups, on the other hand, had a more operational purpose for the network: sharing information on how to carry out attacks in São Paulo and Rio during the Olympic Games. Brazilian police later said they had foiled the planned attacks after investigators infiltrated the group’s WhatsApp chats.

Over the past decade, social media platforms have intensified efforts to tackle terrorist and extremist content by combining artificial intelligence with human review. In 2019, Facebook open-sourced two content-matching technologies — PDQ for photos and TMK+PDQF for videos — designed to detect and block harmful material online. These algorithms create digital hashes, or unique fingerprints, enabling platforms to identify and remove identical or near-identical files, even when altered.

By releasing these tools on GitHub, Facebook empowered tech companies, smaller platforms, and non-profits to detect and remove abusive content more effectively. This open-source approach fosters cross-industry cooperation, allowing multiple services to take down extremist content simultaneously and curb its spread across the internet. On WhatsApp, limits on message forwarding and the monitoring of suspicious activity have also helped restrict the viral circulation of extremist material.

According to a 2024 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), terrorist and violent extremist groups are increasingly exploiting the decentralised web (DWeb), using its messaging apps, social media, and hosting systems such as Skynet and IPFS to distribute content and evade moderation. Indeed, “sustained efforts by major platforms to combat terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) have caused a ‘displacement effect,’ whereby terrorists and violent extremists turn to alternative platforms,” the report said (p.3).

Unlike centralised networks such as Facebook, decentralised platforms allow users to control where data is stored, making them harder to censor or monitor. Services like RocketChat and ZeroNet have become particularly attractive to IS media operatives because their content is hosted on user-run servers, which prevents developers from deleting extremist material. Even when such servers are taken offline, their databases remain intact, reappearing on new servers under new domains — posing fresh challenges for law enforcement agencies attempting to detect and remove jihadist content online.

Propaganda and Cultural Hybridisation

Figure 1: Brazilian group on TechHaven: Brazilian flag overlaid with the ISIS symbol (credit Atlantico Intelligence Group)

Last year, Brazilian police arrested a 45-year-old man accused of being the administrator of the first Latin American jihadist group, aimed at Brazilian and Lusophone users, hosted on a decentralised platform called TechHaven. At his home, officers found chemical materials for bomb-making and a machete — tangible evidence of preparations for violent acts. An analysis of the group’s activities over the three months preceding the man’s arrest reveals a complex structure with two main objectives: disseminating ISIS propaganda and inciting action by sharing technical and military information to carry out attacks. The group was distinguished by its educational and hierarchical approach, with the administrator acting as a cultural mediator to make complex ideological content accessible to a Brazilian audience. He localised ISIS’s global rhetoric to resonate with local sensibilities, blending propaganda from the Amaq Agency—translated into Portuguese—with magazines like Dabiq, Rumiyah, and Voice of Khorasan, and with local cultural references.

For example, the administrator exploited Brazil’s strong musical culture by sharing curated collections of nasheeds (jihadist religious chants) and referencing local texts such as the Brazilian Army’s Jungle Survival Manual to legitimise his message. Operationally, the group circulated technical manuals for attack preparation. The administrator’s final post, showing a Heckler & Koch Mark 23 pistol fitted with a silencer, underscored the shift from theory to intended action.

Figure 2: Brazilian group on TechHaven: final post featuring a handgun (credit Atlantico Intelligence Group)

Although the group primarily targeted a Portuguese-speaking audience and interaction was limited mainly to Brazilian members, foreign users also appeared, requesting materials in English or Urdu (Pakistan’s official language) or sharing links to jihadist groups on the messaging platform Discord.

Figure 3: Brazilian group on TechHaven: a post by a member inviting people to a jihadist group on Discord (credit Atlantico Intelligence Group).

According to Brazilian authorities, the group’s main strength lay in its ability to redirect members to Telegram channels offering military training for “lone wolves.” These channels shared detailed instructions on how to build explosive devices, detonators, suicide vests and belts, as well as manuals for producing and deploying biological and chemical weapons, including phosphine, hydrogen sulphide and cyanide gas. Members of these groups also post requests for cryptocurrency donations to buy materials used for propaganda or to prepare attacks. This shows that extremists sustain their activities through cross-platform migration, swiftly adapting when moderation intervenes. By shifting to smaller or less-regulated platforms, they preserve their networks, rebuild audiences, and continue spreading propaganda.

Decentralised Web Use and Youth Radicalisation

The decentralised web has opened new avenues for accessing jihadist material, making extremist content increasingly difficult to control. In this disjointed ecosystem — lacking central servers or moderation — minors may join encrypted spaces as a game or challenge: navigating the prohibited, disseminating clandestine material, and seeking belonging to an ‘exclusive’ group. A striking example is that of a 14-year-old Uruguayan boy who, according to investigators, was in direct contact with the administrator of the Brazilian extremist group mentioned above. Police arrested him after posting a video threatening to attack a synagogue in Montevideo, Uruguay.

According to the Global Terrorism Index 2025, published by the Sydney-based Institute for Economics and Peace, in Europe, one in five people arrested for terrorism in 2024 was legally classified as a minor (p.2). The report also highlights an increase in lone-actor attacks, rising from 32 in 2023 to 52 in 2024. These attacks are typically carried out by young people, often teenagers, who have no formal links to terrorist organisations. Instead, they become radicalised through online content, developing personal ideologies that blend conflicting viewpoints influenced by “fringe forums, gaming environments, encrypted messaging apps and the dark web” (p.2).

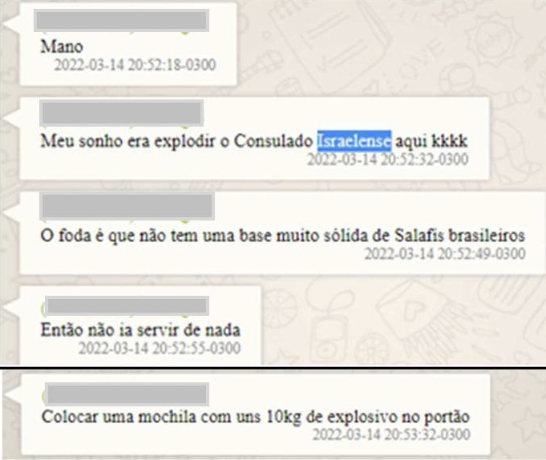

Figure 4: Planning on WhatsApp of the attack by a Brazilian and a minor against the Israeli Consulate in São Paulo (credit Brazilian Federal Police)

Uruguay’s case is not unique. In Brazil, a different young person was part of an investigation that led to the arrest of a 20-year-old in 2023. This person was apparently prepared to travel to Turkey to fight with ISIS. The Federal Police found that the youngster had been groomed on Telegram and told on WhatsApp to prepare assaults against the Israeli embassy in Brasília and the consulate in São Paulo.

Their discussions indicated a worrying rise: in addition to sharing ISIS propaganda, the two exchanged technical advice for making bombs and improvised explosive devices. The older suspect had also posted a video on pCloud, wearing a mask and responding to a questionnaire for prospective ISIS recruits. Police documents noted: “data provided by Google revealed the young man’s interest in Islamism, as shown by his search history, as well as a fascination with Nazi-inspired ideology”.

Figure 5: Excerpt from the investigation (credit Brazilian Federal Police)

In both cases, antisemitism emerged as a central driver of radicalisation, fuelled by online environments that promote hatred and conspiracy theories. Additionally, structural issues such as poor educational attainment, social isolation, and limited opportunities in disadvantaged environments create a climate conducive to extremist ideology.

Recommendations

DWeb, by its very nature, decentralised and resistant to censorship, represents one of the most complex challenges for contemporary counter-terrorism strategies. Within this ecosystem, platforms such as ZeroNet and applications based on protocols like Matrix (for instance, Element) offer jihadist networks new spaces to disseminate propaganda, recruit followers, and communicate through encrypted channels that are difficult to monitor or dismantle. ZeroNet functions similarly to a traditional website but distributes its content across users via peer-to-peer (P2P) technology, eliminating a central server and thereby frustrating censorship or content removal. Matrix, meanwhile, is a decentralised communication protocol that enables interoperability between servers and applications. Element, one of its best-known applications, provides end-to-end encrypted messaging, group chats, and public or private channels, similar to Telegram or Discord but without dependence on a single provider.

Facing this reality requires a strategic reevaluation of prevention and counteraction measures.

The priority must be to strengthen technological surveillance and analytical capabilities by developing advanced monitoring tools that operate on decentralised networks. Combining artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning would help simplify the identification of traffic patterns and unusual nodes linked to terrorist activity in the decentralised web. At the same time, focused disruption attempts could make it harder for jihadist groups to have a continuous online presence by limiting access to channels used to spread extremist content. As the internet becomes increasingly decentralised, regulated platforms such as Discord and Facebook have an even more crucial anchoring role to play. Among the actions required is better interoperability in safety measures — developing shared standards for content moderation signals, user verification, and abuse detection that can interface with decentralised or federated systems. User education and the introduction of friction tools are also essential. When users click on links that take them to less-moderated or decentralised environments (such as encrypted chats, peer-to-peer sites, or federated servers), platforms should display a safety interstitial — a brief warning or consent screen. This message could alert users that they are leaving a moderated space, explain the risks of exposure to illegal or misleading content, request consent to proceed, and offer further resources on online safety.

But improved technological measures alone are not enough. A coordinated global effort between intelligence agencies, law enforcement, and technology companies is essential. Establishing specialist task forces, primarily those focused on open-source protocols, might facilitate the creation of ‘ethical backdoors’ or obligatory audit procedures that provide limited oversight without compromising the fundamental principles of decentralisation that characterise the DWeb. Simultaneously, legal and regulatory frameworks must be revised to include clear stipulations mandating the removal or obstruction of terrorist material, even from decentralised nodes. Given that several DWeb sites use blockchain technology, it is essential to implement procedures to monitor and freeze digital wallets linked to terrorist funding. Ultimately, counter-radicalisation initiatives must also include the societal aspect, especially in Latin America. Addressing the fundamental roots of extremism—namely, poverty, inequality, and young marginalisation—requires providing concrete chances in the real world to mitigate the digital isolation that often leads to online radicalisation.

–

Maria Zuppello is an Italian journalist based in São Paulo, Brazil, with a background in investigative reporting. She has covered Latin America for several international media outlets, including The Guardian, Agence France-Presse and Infobae. Her work focuses on the crime–terror nexus, with a particular emphasis on jihadist networks in Latin America. X: https://x.com/mariazuppello

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.