This Insight analyses potential security threats associated with the use of 3D-printing technologies for the production of firearms and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) components by jihadist actors, amidst their growing interest in this capability. Western countries are assessed to be particularly exposed to this threat. These risks stem from the widespread availability of these technologies and the concentration of documented cases involving 3D-printed firearms among violent non-state actors. The Insight concludes that in the short term, 3D-printed weaponry appears to function as a supplementary or experimental capability within the jihadist arsenal.

Throughout the fall of 2025, two cases involving attempts to use 3D-printing by jihadists have been reported in Europe and North America. This continues the trend of a gradual incorporation of these technologies among extremists in planning attacks worldwide, in particular in Western countries.

On 19 October 2025, Belgian authorities thwarted a jihadist-inspired attack in the country by arresting three young suspects in the city of Antwerp. According to Belgium’s Federal Prosecutor Ann Fransen, the arrest was a part of an investigation into “attempted terrorist murder and participation in the activities of a terrorist group.” The name of the group to which the detainees were affiliated, however, was not disclosed by the Belgian authorities. While intending to attack political figures, among other targets, the suspects reportedly aimed to use UAV-mounted explosives. Given that a 3D printer was discovered during police searches at one of the suspects’ homes, Belgian authorities stated that the suspects likely intended to manufacture certain UAV components with the use of 3D-printing.

Another case involving plans by an extremist to use 3D technology was reported in the United States in September 2025, when a former US Army National Guard member was charged with attempting to provide 3D-printed firearms to Al-Qaeda. According to the US Department of Justice, Andrew Scott Hastings was initially identified by the FBI in June 2024 when he was discussing global jihad and committing violence against US citizens on social media. Later, he was communicating with an undercover agent claiming to be tied to Al-Qaeda about acquiring 3D-printed firearms, machine gun conversion devices and UAVs.

Subsequently, Hastings provided the agent with a link to a website where 3D-printed weapons were offered for sale. He was also attempting to ship, via postal service, boxes with over 100 3D-printed machine gun conversion devices, two 3D-printed lower receivers for a handgun, and various handgun parts to be supplied to Al-Qaeda. Hastings believed that the above-mentioned devices were intended for use in terrorist attacks planned by the group.

In 2023, two individuals in the UK were separately charged with producing and possessing components of 3D-printed weapons. One, a Birmingham University student, Mohammad Al-Bared, was jailed for manufacturing a “kamikaze” drone using a 3D printer to deliver an explosive device or chemical weapon for ISIS members, while planning to join the group in West Africa afterwards. Meanwhile, another individual, Abdiwhid Abdulkadir Mohamed, was prosecuted for possessing documents likely to be useful for committing acts of terrorism, including manuals on printing 3D firearms.

Figure 1. A photo of the UAV built by Mohammad Al-Bared using 3D printing (Obtained from The Guardian)

The aforementioned reports indicate a potentially new phase in the jihadist “do-it-yourself” (DIY) approach in which 3D printing may play a more prominent role. It is also noteworthy that this technology appears particularly popular for UAV production, likely due to its ease of use and demonstrated stability and efficiency in various conflict zones.

3D-Printing Technology in Jihadist Media and Online Communities

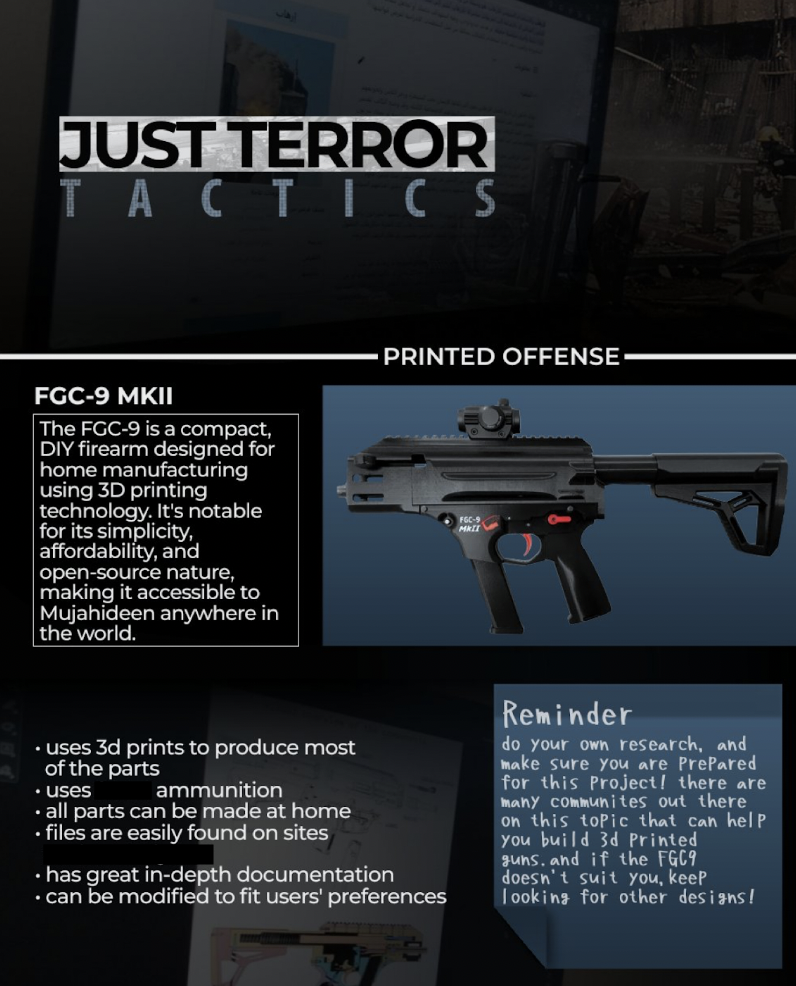

In parallel with individual attempts to use 3D printers in jihadist-inspired attacks, the media apparatus of global jihadist groups has also begun to focus on this technology. For example, in October 2024, an instructional poster designed by a little-known media outlet affiliated with ISIS reportedly circulated across pro-ISIS social media platforms. The poster encouraged ISIS sympathisers to manufacture a 3D-printable firearm, the FGC-9 Mk2, to be used in lone-actor attacks around the globe. The firearm was described by the pro-ISIS media agency as “notable for its simplicity and affordability” and “accessible to Mujahideen anywhere in the world.” Notably, the FGC-9 is one of the world’s most popular 3D-printed guns that has been widely adopted and used by far-right extremists and criminal groups globally.

Figure 2. A poster by an unofficial pro-ISIS media outlet inciting supporters to manufacture the 3D-printable firearm FGC-9 Mk2 (Obtained from TRACTerrorism).

More recently, in March 2025, another pro-ISIS media outlet published a manual in English and Arabic that included instructions on how to equip UAVs with a video system using 3D-printed mounts. In particular, the manual explained how UAV video systems can be integrated into the drone’s existing hardware and software. Instructional content like this provides insight into how accessible dangerous-material building has become in a short time.

Over the past year, pro-ISIS and pro-Al-Qaeda users have also expressed an increased interest in 3D-printed weaponry on encrypted messaging platforms. While promoting the use of 3D-printed rifles in attacks, particularly in countries with limited access to conventional weapons, users shared manuals for such firearms and links to online platforms offering designs and technical information related to 3D-printable guns.

Furthermore, a July 2024 report by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) indicated that Al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, Al-Shabaab, was identified as already experimenting with 3D-printing technology to produce weapons and components for adapting commercial unmanned aerial systems. In addition, the report emphasised a general increase in the exploitation of 3D printing and other technologies by groups affiliated with ISIS and Al-Qaeda around the globe.

Overview of 3D-Printed Firearms Proliferation Among Violent Non-State Actors

The proliferation of 3D-printed firearms among violent non-state actors is generally not a new occurrence. Due to their cost-effectiveness, these firearms have become significantly prevalent over the past decade, raising concerns among security authorities worldwide. In particular, recent studies by Schaufelbühl et al., Basra, Veilleux-Lepage, Dass, and others indicate a dramatic increase in incidents involving 3D-printed firearms since 2021. The study by Schaufelbühl et al. also notes that Europe, North America, and Oceania have the highest concentrations of documented 3D-printed weaponry cases.

However, the aforementioned increase in the use of 3D-printed firearms applies primarily to far-right extremist and criminal networks, while jihadists still appear to be at the early stage of the exploitation of this technology. Nevertheless, the trends outlined above suggest a growing interest in such weaponry among jihadist actors, who are constantly seeking the most accessible but effective tools for carrying out attacks, while gradually integrating high technology into their modus operandi.

Such a lag in the adoption of 3D-printed weapons may result from specific features of propaganda materials published by pro-ISIS and pro-Al-Qaeda media outlets. Currently, jihadist media products continue to prioritise the accessibility of methods for conducting lone-actor attacks, placing an emphasis on low-tech and widely available means, including knives, vehicles and arson attacks. These attack tools are readily accessible and have long proven effective in terms of their lethality, and their acquisition is unlikely to raise suspicion. For example, the 2017 vehicle-ramming attack in Barcelona, Spain, the 2016 truck attack in Nice, France and similar car-ramming attacks are frequently cited in jihadist propaganda as successful models for future attacks that did not require specialised equipment or technical knowledge. Furthermore, an unclear “legal” status of 3D-printed weapons may pose an additional obstacle to the integration of this technology among jihadists, as no official fatwas (Islamic religious edicts) issued by ISIS or Al-Qaeda scholars have been identified as of this writing.

More recently, UAVs have also been promoted by media outlets affiliated with ISIS and Al-Qaeda as a relatively new means for lone-actor attacks. Their operational value has been repeatedly demonstrated in various conflict zones, including the current Russia-Ukraine war. In this context, the promotion of UAVs illustrates how jihadist groups gradually and selectively integrate new technologies into their propaganda apparatus once their effectiveness has been demonstrated elsewhere. Such a trend applies to 3D-printed weaponry as well, whose adoption among jihadist groups will likely expand in the long term, albeit within a specific operational niche. Nevertheless, it remains unlikely that “traditional” attack methods will be fully replaced by 3D-printed weapons, given the wide availability of low-tech alternatives.

Conclusion and Implications

The cost of 3D-printing technology and its manufacturing capabilities continues to decline, resulting in the increased accessibility of these tools among violent non-state actors globally. This trend is particularly relevant for Western countries, which, as of this writing, demonstrate the highest concentration of registered cases of 3D-printed firearms.

The recent jihadist-related cases involving 3D-printing technology in Belgium, the UK and the US, alongside the growing attention to this capability within pro-ISIS and pro-Al-Qaeda media outlets and online communities, indicate an emerging interest by jihadist actors in this technology. Furthermore, the UN report noting that Al-Shabaab elements are engaging with 3D-printed weapons further supports this assessment. In this context, a threat associated with the broader use of 3D-printed weaponry by jihadists appears to primarily affect Europe, North America and Oceania, as it has been observed among far-right extremist groups. Most likely, a successful jihadist attack involving 3D printing, in addition to the continued promotion of this technology in jihadist propaganda, would significantly increase the risk of wider uptake of 3D-printed firearms among Al-Qaeda and ISIS supporters in the future.

At the same time, the pace of proliferation of 3D-printed weaponry may be significantly constrained by several factors, including the continued availability of conventional weapons. It should be noted that despite the frequent crackdown measures by law enforcement worldwide, the illicit trade of firearms via dark web ecosystems is still active. Furthermore, due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, there are risks of the diversion of small arms and guided infantry weapons into other countries in Europe and beyond. In any scenario, 3D-printed firearms should be understood as a supplementary capability within the militant arsenal rather than a complete replacement for the existing attack methods, posing an additional security challenge. This highlights, therefore, the necessity of continued monitoring of developments in 3D-printing technologies as well as their representation within jihadist propaganda materials and online communities.

–

Sergey Elkind is a former Israeli intelligence analyst and a geopolitical researcher with expertise in OSINT investigations and online threat environments. His professional interests include the study of jihadist and militant online activity, as well as the analysis of their propaganda materials and techniques. Currently, he is applying his background and skills in the German civic sector, where he coordinates intercultural initiatives that foster dialogue, inclusion and social resilience.

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.