The fatal stabbing of a 10-year-old Tajik immigrant schoolboy in the Odintsovo district of Moscow Oblast on 16 December 2025 was not an isolated act of violence. It reflects two broader patterns: signs of entanglement of Russian far-right subcultures with transnational online ecosystems, and a hybrid radicalisation pathway combining structured far-right ideology with more diffuse, nihilistic worldviews lacking coherent political goals. This Insight examines how personal grievance and exposure to ideological bricolage drawn from Western far-right and school-attack milieus – amplified through digital platforms – contributed to performative violence and outlines the implications for prevention and platform governance.

Livestreaming Hate Violence and the Pursuit of Notoriety

The attacker, a 15-year-old Russian student identified as Timofey K., attended the same school as the victim. After asking Qobiljon (rendered as Kobiljon in Russian transliteration) Aliev about his nationality and confirming that he was Tajik, Timofey fatally stabbed the child. A school security guard who attempted to intervene was incapacitated after the attacker sprayed pepper spray into his eyes and stabbed him. Timofey livestreamed much of the attack on his Telegram channel, took selfies with the victim, and shared images and video recordings via a class chat. The footage rapidly circulated across social media platforms, indicating an intent not only to commit violence but also to document and disseminate it widely for public exposure.

The victim’s family had moved from Tajikistan to Russia four years ago after his father passed away. His mother worked as a cleaner at the same school. The killing prompted a diplomatic response, with Tajikistan’s Foreign Ministry calling it “motivated by ethnic hatred,” and the Russian president offering condolences while describing the attack as an “act of terrorism.” The attacker was detained at the scene, and criminal proceedings for murder are ongoing.

Available reports indicate that on the day of the attack, Timofey initially sought out a mathematics teacher as his intended target, whom he perceived as overly strict and blamed for reprimands over poor academic performance and absences. School staff later noted declining academic results, frequent absenteeism, and increasing social isolation, while social media users alleged bullying and episodes of public humiliation by his peers.

These factors help explain the emotional distress of the perpetrator, but not why the violence took a deliberate, symbolic, and publicly staged form. Timofey appears to have come to the school with a clear intent to carry out an attack. When questioned by a teacher about his appearance shortly before the attack, he responded, “You will read about it on Wikipedia,” and added, “I don’t care if I get life,” signalling an expectation of notoriety. After failing to locate his initial target, he redirected his violence toward the victim.

Investigators later discovered a homemade device resembling an explosive detonator in a school toilet (Figure 1). The attacker had brought the device into the school concealed in his backpack, along with a military-style helmet and vest, and equipped himself with it after passing the security check (Figure 2). It remains unclear whether the device was functional or merely a mock-up. Nevertheless, its construction and transport suggest premeditation and an aspiration to cause greater harm had the attacker possessed the necessary skills and components.

Figure 1. The items seized from the assailant following the attack. Source: Gazeta.ru (16 December 2025).

Figure 2. Selfie taken by the assailant shortly before the attack. Source: Novaya Gazeta Europe (16 December 2025).

Digital Manifesto as Motivational Disclosure and Moral Framing

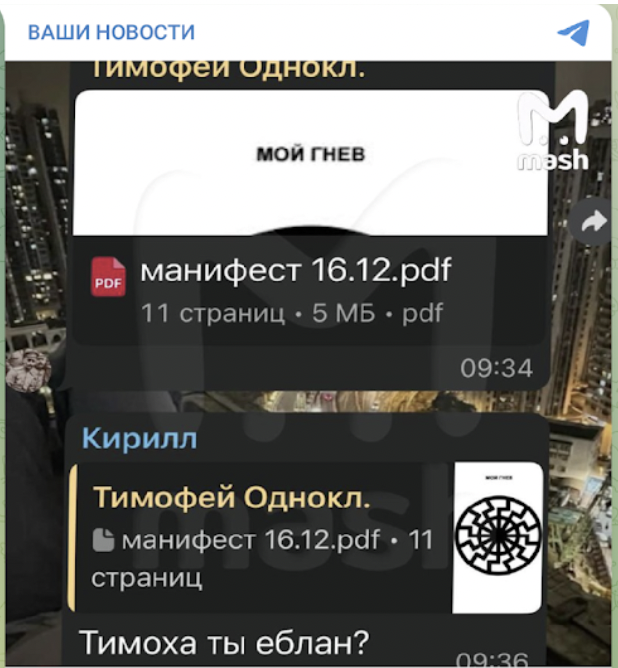

A day before the attack, Timofey shared an 11-page manifesto titled “Moy gnev” (“My Anger”) in a class chat (Figure 3). Although the text included instructions related to weapons and explosives, it contained no explicit indication of an imminent attack, and classmates later said they dismissed it as similar to material he had circulated online for at least a year and a half. This timeframe likely marks the onset of his engagement with online extremist content.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the class chat following the posting of the manifesto. Source: Vashi Novosti (16 December 2025).

Analysis of the manifesto indicates that the emotional and ideological core of his radicalisation centred on perceived humiliation, exclusion, and a belief that his Christian identity was under threat. The manifesto opens with a quotation from Eric Harris, one of the perpetrators of the 1999 Columbine High School massacre in Colorado, expressing hatred toward people. This suggests symbolic alignment with earlier school attackers and their grievance-driven logic.

Timofey claimed that he had been “suffering in this f…king school” for nine years. Reports of bullying, academic decline, and social isolation align with this self-narrative, suggesting that he experienced school as a continuous injustice, generating resentment not only toward individuals but toward society more broadly. He expressed hatred toward society and dehumanised others as “biowaste,” writing: “Lives do not matter, and you people, through your disgusting behaviour toward me, have only confirmed this.” This rhetoric reflects elements of nihilistic and misanthropic thinking that dismiss human life as inherently meaningless.

The manifesto frames Christianity as under threat and presents mass killing as a form of “defence.” It dehumanises Muslims as a “plague” and scapegoats Jews, liberals, leftists, opposition, and LGBT minority groups as sources of societal decay. His racist rhetoric also extended to Chinese and Mexicans, whom he described as “non-white by definition.” References to the far-right “Great Replacement” conspiracy situate these views within a white-supremacist ideological framework that casts immigrants and Muslims as cultural threats. Combined with nihilistic and misanthropic themes, this identity-based, conspiracy-driven worldview functions as a moral and motivational framework that legitimises violence, positioning the Tajik victim, who was a visibly Muslim immigrant child, as a symbolic and permissible target.

Ideological Bricolage and the Imitation of Western School Attacks

Based on news reports and classmates’ retrospective accounts of his online behaviour, Timofey’s engagement with far-right and nihilistic content appears to have developed at least over a year and a half prior to the attack, suggesting a gradual radicalisation process. His parents claim not to have anticipated that he would commit such a violent act. The evidence points to a process shaped by sustained online exposure, rather than by recruitment or direct coordination by any handler identified to date.

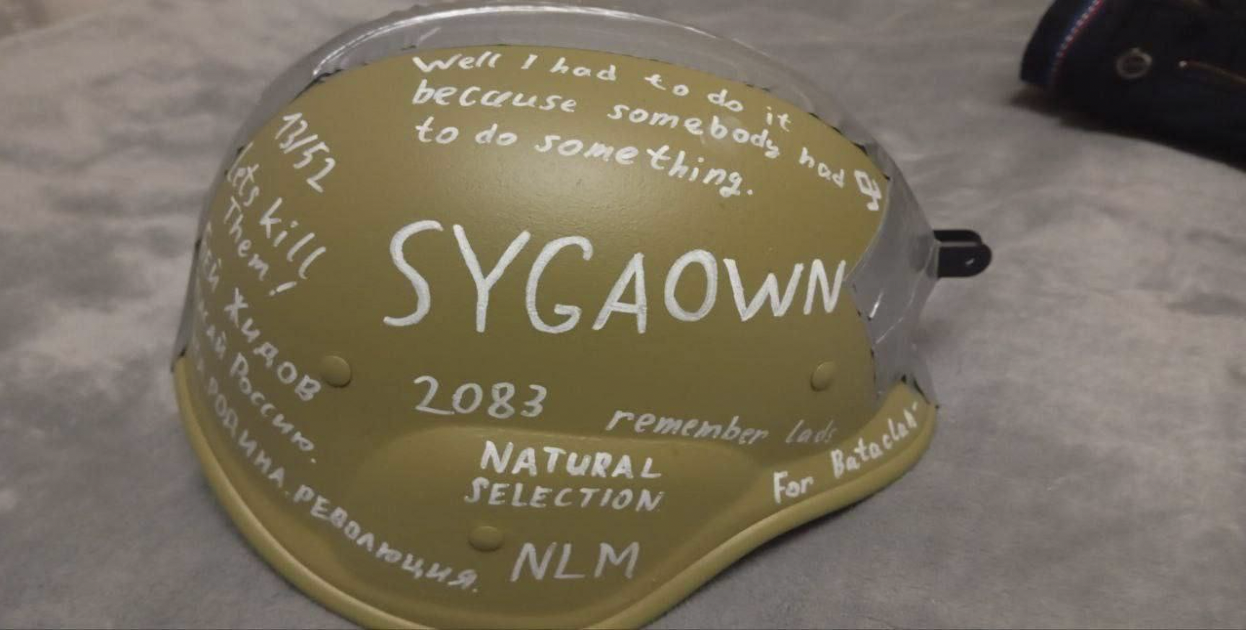

Crucially, Timofey was not merely a passive consumer but an active participant in online extremist subcultures characterised by ideological bricolage – a selective mixing of narrative and symbolic elements drawn from multiple extremist environments rather than adherence to a single coherent ideology. During the attack, he wore clothing and equipment displaying a combination of far-right and nihilistic symbols (Figure 4). Explicit far-right and white-supremacist markers included the Slavic neo-pagan kolovrat, a Celtic cross, references to the “Great Replacement,” numerological codes such as “13/52” (a racist crime statistic trope) and “2083” (the title of Anders Breivik’s manifesto), slogans like “Beat the Jews – Save Russia!”, “Sygaown,” and references to the Christchurch attack, including the number “51” (the Christchurch attack death toll) and birthday greetings to Brenton Tarrant.

Alongside these were expressions more closely associated with nihilistic violent extremism, a form of violence driven by grievance, misanthropy, and a search for significance rather than a coherent ideological or political agenda. These included slogans such as “No Lives Matter,” “Natural Selection,” “Let’s kill them!,” “Well I had to do it because somebody had to do something,” and “For Bataclan.”

Figure 4. The attacker’s helmet with extremist slogans. Source: Novaya Gazeta Europe (16 December 2025).

The presence of these references, despite the attacker’s limited English proficiency, underscores how Western extremist symbols and attack scripts are translated and circulated within Russian-language online ecosystems, facilitating their local adoption.

Timofey was active in several far-right-linked online communities, including “Ne Toleranten” (“Not Tolerant”) and “Ne Mir no Mech” (“No Peace but a Sword”), where he glorified mass killers. According to Neolurk, a Russian-language meme and subculture wiki, “Ne Toleranten” has around 50,000 followers on VK and 5,000 on Telegram and presents itself as satirical but promotes an explicitly anti-immigrant and anti-tolerance worldview, using dehumanising and conspiratorial narratives.

The visual and performative aspects of Timofey’s actions, including manifesto writing, filming the attack, selfies, extremist clothing, and references to Western mass killers, closely resemble patterns observed in the United States, Europe, Australasia, and, more recently, Southeast Asia. This differs from earlier forms of Russian neo-Nazi activity, such as skinhead gangs, which were typically organisational, street-based, and locally rooted. Overall, this hybrid, digitally mediated form of radicalisation, in which personal grievance, notoriety-seeking, and school-shooter imitation intersect with identity-based extremist narratives, poses distinct challenges for detection, monitoring, and prevention.

Implications for Tech Policy and Prevention

Although Russia has experienced instances of school violence, racist and xenophobic hate attacks on schools have been rare, and until recently, none were documented as being committed by minors. One known case took place on 9 April 2025, when a Russian adolescent in the Nekrasovsky district of Moscow Oblast fatally stabbed a nine-year-old boy from Kyrgyzstan, on grounds of ethnic hatred. The stabbing took place in the residential dormitory rather than at school, but the two were schoolmates. While the Nekrasovsky attacker reportedly accessed a skinhead website, gaps in available reporting limit detailed analysis of his motivations and pathway to radicalisation.

Taken together, these cases point to a concerning pattern of early-onset, identity-based, school attack memetic violence by minors, posing significant challenges for prevention and platform governance. While Russia maintains mechanisms to police traditional far-right extremism, contemporary youth radicalisation is increasingly diffuse, symbolic, and embedded in online subcultures, making it difficult to detect through usual indicators.

Comparable attacks beyond Russia, including the Bandar Utama school stabbing in Malaysia (October 2025) and the Jakarta school bombing in Indonesia (November 2025), reinforce the transnational nature of this pattern. In each case, minors carried out lone-actor attacks in their own schools following radicalisation shaped by diffuse online extremist ecosystems, emulating Western school shooters such as Eric Harris and drawing on shared manifestos and symbols. This points to cross-border replication of age profiles, motivations, and methods enabled by digital platforms.

Timofey’s long-term participation in extremist chats and forums suggests missed opportunities for early intervention. Indicators such as explicit hate speech targeting ethnic and religious groups, competitive glorification of violence, attacker fandom, and performative self-presentation could, if properly contextualised, serve as risk signals for platforms, moderators, family members, and educators. This underscores the need for improved cooperation between authorities and technology platforms. At the institutional level, the case exposes weaknesses in school security and preparedness. The attacker brought a knife and a homemade explosive device into the school, highlighting the need for enhanced detection measures, staff training, and security readiness. However, technical fixes alone are insufficient.

The growing visibility of symbolism associated with undesignated far-right and nihilistic milieus underscores the importance of early legal and regulatory responses. For platforms, the challenge extends beyond content removal to recognising how recommendation systems and community dynamics can sustain and normalise violent behaviour. Without addressing these structural factors, future attackers may continue to emerge from networked and algorithmically reinforced online spaces.

Researchers in Russia have noted contradictory and selective portrayals of immigrant “criminality” and “otherness” in the discourse of some media outlets and public figures. Such irresponsible framing contributes to an information environment that extremist subcultures can readily appropriate and distort to boost their own propaganda messaging. To reduce downstream amplification risks, more consistent, contextualised, and responsibility-aware public communication is essential.

The online circulation of footage from the stabbing generated widespread public resonance and condemnation across Central Asia and Russia. However, it also risks fuelling further radicalisation across ideological spectra and reinforcing cycles of retaliatory violence. Such attacks are not driven by ideology or grievance alone but also by a strategic logic that anticipates online visibility, recognition, and destabilising effects on targeted communities. While it may not be feasible to remove harmful content entirely from private exchanges, particularly on encrypted networking platforms, there is evidence that rapid takedowns can significantly reduce wider circulation on major social media services. Even where violent content persists, platforms can still mitigate risk by limiting its amplification, resharing, replay, and algorithmic promotion.

–

Nodirbek Soliev is a PhD candidate at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He previously worked as a Senior Analyst at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), RSIS. With nearly fifteen years of experience studying radicalisation, extremism, and terrorism, his research focuses on Central Asia, China’s Xinjiang region, and, periodically Russia.

–

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.