Note: The following Insight draws on research conducted by Sonja Belkin and Kristy Sakano under the DoD–funded UC2 Cybercrime Collaboration at National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), University of Maryland.

Content warning: this Insight contains mentions of suicide.

What is Cyberhacktivism?

In June 2025, as conflict between Iran and Israel escalated, cyberhacktivism – a portmanteau of ‘hacking’ and ‘activism’ – surged. The cyberhacktivist collective Predatory Sparrow, which had previously claimed responsibility for cyberattacks that triggered explosions at three Iranian steel manufacturing facilities in 2022, launched an attack against Iran’s state-owned Bank Sepah, forcing branch closures and disrupting customer access. In retaliation, a hacking group affiliated with Al-Qaeda – The Cyber Jihad Movement – launched Operation Storm. This operation involved a series of cyberattacks against ‘hostile targets’: namely, US and Israeli digital infrastructure, which included banks, news organisations, the military, and telecommunication companies.

Cyberattacks are on the rise across the spectrum of ideological extremism. Hacktivist groups like DieNet, who align themselves with Shiite militant factions in Iraq, have organised campaigns targeting critical infrastructure to retaliate against Western imperialism and US dominance. The Holy League collective, by contrast, claims to have defended Christian values and Western civilisation by targeting LGBTQ+ organisations and abortion providers.

Although there is undoubtedly growing concern about cyber incidents, as evidenced by the first global treaty against cybercrime, currently open for signature at the UN, cyberhacktivism remains underexplored. Like cybercriminals, cyberhacktivists employ a broad range of disruptive tactics, including disabling communications infrastructure, obstructing access to websites, and leaking confidential or classified information. As digital access and cyber capabilities have expanded, cyberhacktivism – like cybercrime – has become increasingly sophisticated, moving beyond website defacements and temporary service disruptions towards more consequential operations, like the aforementioned critical infrastructure damage inflicted by Predatory Sparrow in 2022. Crucially, what sets cyberhacktivism apart from cybercrime is not the method but the motivation; cyberhacktivism specifically refers to the ideologically driven use of cyber intrusion techniques.

A technical approach – such as categorising common hacking techniques – is insufficient to address cyberhacktivism; without examining the mechanisms that drive individual participation and mobilisation, limiting radicalisation may prove difficult, thereby increasing the risk of cyberhacktivism. This Insight applies a socio-psychological framework, grounded in social contagion theory, to characterise who becomes a cyberhacktivist and why. It assesses the threat horizon for radicalisation into extremism-driven cyberhacktivism and proposes behavioural science interventions that may limit recruitment among vulnerable individuals.

Cyberhacktivism Through a Social Contagion Lens

To understand extremist cyberhacktivism, practitioners must consider micro-level factors – for instance, what individual traits might predict susceptibility to recruitment? Simultaneously, it must include macro-level factors: the structure of social networks, for instance, can predict the rate at which cyberhacktivist behaviours spread. One compelling way to integrate micro- and macro-level mechanisms is through the lens of social contagion.

Social contagion effects have been most prominently studied in the context of celebrity suicide. One example of this is the Werther effect, which describes how celebrity suicide can trigger ‘copycat’ incidents, particularly among high-risk individuals who perceive themselves as sharing characteristics, such as age or gender, with the celebrity. Paralleling the pathogens through which biological contagion spreads, social contagion is transmitted through cultural scripts: narratives that disseminate societal values, behaviours, and norms. In particular, social contagions require four elements to spread, relating both to the source of the information and the information itself. Firstly, the information must be communicated via a ‘one-to-many’ broadcast. Secondly, it must be coherent and actionable – including both an idea for what to do and a template method for how to do so. Finally, the information must be expressed by (third) a source with notoriety, whom the high-risk population views as (fourth) similar to themselves.

Research from Clancy and Oviatt in 2023 postulated the ‘terror contagion hypothesis’ – that violent radicalisation follows similar contagion dynamics to the Werther effect. In this context, cultural scripts communicate ideological grievances alongside modus operandi for public mass killing attacks. When such grievances are coherently and clearly articulated – consider, for instance, Brenton Tarrant’s comparatively accessible 74-page manifesto to Anders Breivik’s sprawling 1,500-page manifesto – they increase in memetic potential, facilitating wider circulation. When this is combined with high incident notoriety, high-risk individuals who perceive themselves as ‘self-similar’ to the original actors become increasingly likely to carry out copycat extremist acts. In a highly connected online world, cultural scripts are not limited by national boundaries and can proliferate globally, as shown by the spread of Columbine, VA Tech, and ‘incel’ terror contagions.

Similar to terrorism and suicide contagions, mobilisation within extremist-aligned cyberhacktivist collectives can often involve shared grievances and highly visible, symbolic events that resonate globally. In these networks, cultural scripts might circulate rapidly, prompting imitation among those who identify with the cause. Anonymity may also lower the self-similarity barrier, possibly making other factors – like shared grievances and methods – more potent. In addition to making cyberhacktivism more accessible, LLMs may further amplify ideological grievances, increasing the likelihood of contagion. Indeed, experimental evidence shows that when prompted to fulfil a hidden agenda, LLM-based chatbots can persuade some individuals to run suspicious code in their browsers, even after participants were explicitly warned that the system was “experimental” and potentially untrustworthy.

Thus, while direct evidence of extremist cyberhacktivist behaviour spreading through contagion dynamics remains limited, a social contagion lens can provide the first step towards elucidating the psychological components of extremist cyberhacktivism.

Cyberhacktivist Radicalisation

Typically, cyberhacktivist networks are decentralised and loosely organised. This is exemplified by collectives like Anonymous, which describe themselves as a ‘flock of birds’. In other words, members follow a swarm-like model during operations, in which anyone can propose a target, and others may join, absent formal leadership or a chain of command. Yet, despite the decentralisation of leadership, informal hierarchies of engagement continue to guide how individuals enter, participate, and escalate within hacktivist ecosystems.

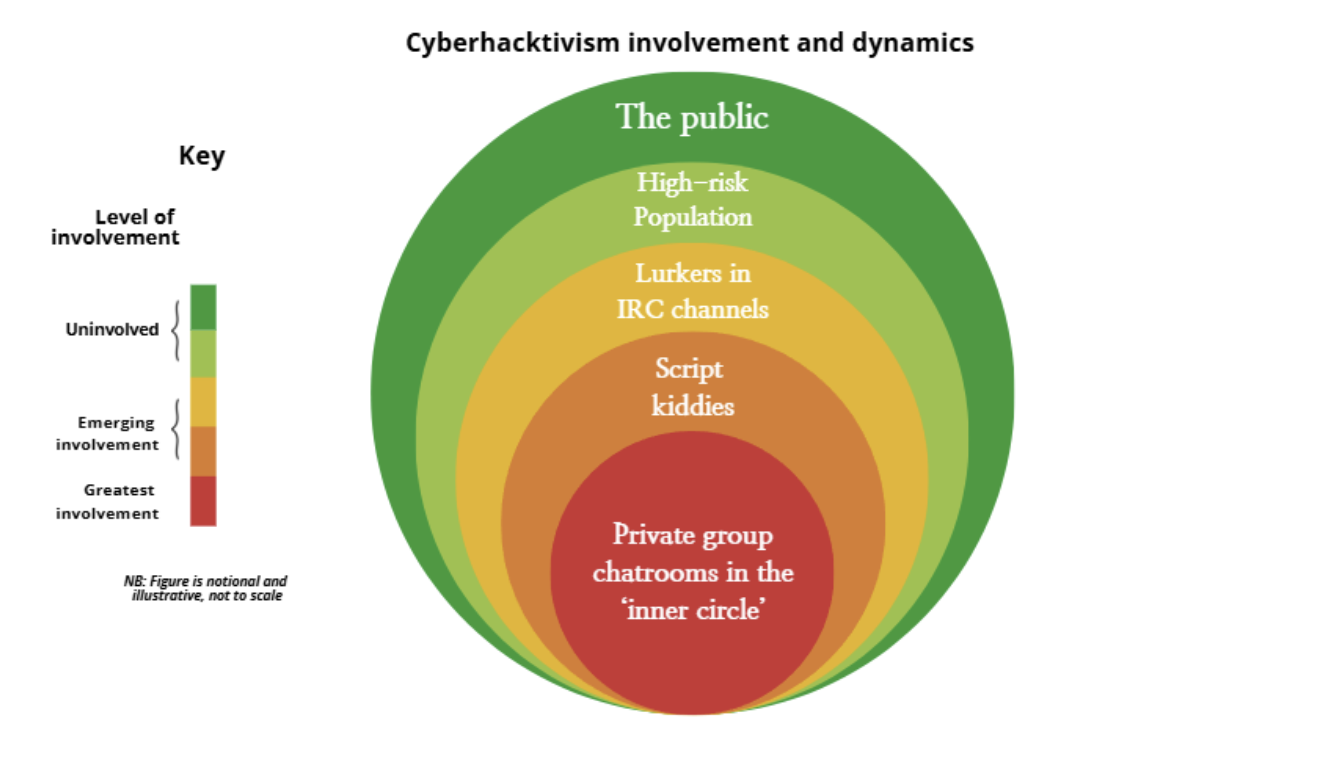

Ethnographies of groups like Anonymous illustrate this spectrum of engagement levels. At the outermost layer are low-engagement participants – one-off recruits mobilised via ‘batsignal’ calls on social media platforms to amplify time-limited operations, often by spreading awareness of operations using a relevant hashtag. Once drawn in, participants may progress to lurking in public Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels, where they observe ongoing activity, and subsequently transition to more active roles.

For those without technical expertise, this could include taking the role of a script kiddie – a less skilled individual who uses pre-written tools to participate in cyberattacks. Finally, the innermost layer is the most exclusive, consisting of private, invite-only chatrooms where planning and coordination take place. Interviews with hacktivists confirm this, describing smaller, more enduring cores, with rings of casual helpers. Consequently, we can understand cyberhacktivist networks through a layered engagement structure, as visualised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A visualisation of the spectrum of cyberhacktivist engagement. NB: The above figure is notional and illustrative, not to scale (graphic designed by the author).

Taking each of these layers in turn, we can better conceptualise the risks of increasing radicalisation. Among a high-risk population, for instance, we should be most concerned with the promotion of cultural scripts that focus on ideological grievances. These can have a secondary effect of eroding institutional trust and civic participation, which correlates with increased public support for hacktivism. This creates a potential feedback loop in which high-risk individuals on social media unintentionally amplify trust-eroding narratives, thereby increasing the likelihood that others will be drawn into actively participating in hacktivist activity.

Lurkers in extreme hacktivist IRC channels are likely to be the most vulnerable to radicalisation: observing hacktivist activity without yet participating, these individuals are often emotionally driven and sympathetic to extremist cyberhacktivism, but may lack confidence or technical skill. Individuals who become cyberhacktivists are often driven by outrage and frustration in response to a perceived violation of their moral principles. Over time, this moral outrage may solidify into a long-term grievance that motivates them to seek justice. This provides a fertile population for contagion when the relevant cultural scripts are circulated. For instance, broadcasting nationalistic slogans might exploit existing grievances, tipping lurkers over the edge into mobilisation. Indeed, in areas with high geopolitical tension, nationalist sentiment is a key motivator for cyberhacktivism – but this doesn’t appear to be as relevant among European or North American hacktivists.

Lurkers’ psychological resistance to active involvement may be lowered by the provision of mentorship. For instance, hacktivist groups like GhostSec have previously created cyber training initiatives, so as to lower barriers for newcomers with a grievance to enter the world of ideological hacking. Equally, psychological phenomena like the ‘foot-in-the-door-effect’ might make the leap from passive observation to participation feel smaller and socially validated. For instance, encouraging low-cost, low-risk behaviours – like reposting a call for recruits – can gradually increase lurkers’ commitment. Each subsequent, more substantial request, such as running an existing DDoS script, thus becomes psychologically easier to justify.

Belief in one’s ability to effect change, known as efficacy, is a key motivational driver in hacktivist engagement; a recent study interviewing 28 hacktivists found that every participant cited efficacy as a necessary precursor to their first-time hacktivist participation. Importantly, efficacy alone cannot create the conditions for hacktivism; rather, it becomes relevant when individuals’ moral values are violated. This trigger leads to a desire to engage in collective action.

Posts in IRC channels may also create social pressure to engage in operations, particularly where rivalries with opposing hacktivist groups might be invoked. Using ‘us vs them’ framing can heighten in-group cohesion and conformity pressure, making individuals more comfortable joining collectives affiliated with extremist ideologies, like The Cyber Jihad Movement.

Interventions for Media, Tech Companies, and Policymakers

This analysis suggests two key points for intervention, aimed at reducing the likelihood of recruitment and mitigating the cognitive impact of these attacks on their targets. Combining a social contagion lens with the principles of behavioural science can provide several promising directions.

Reducing recruitment

One strategy to reduce extremist cyberhacktivist contagion among would-be recruits would be to reduce the appeal of culturally coherent scripts. For instance, in the context of suicide contagion, the Papageno effect shows how information ecosystems can have a preventative effect on imitative suicidal behaviour, especially media coverage which emphasises the ‘non-attractiveness’ of the act. Applied to public mass killings, systems modelling has suggested that obscuring self-similarity and coherence – making the method and grievance more incomprehensible to the public – might also minimise the spread of culturally coherent scripts.

Similar defences could feasibly be trialled to deter extremist cyberhacktivist contagion. Media coverage could highlight ‘non-attractiveness’ by challenging the perception that cyberhacktivism carries little personal risk. For instance, the fallout from operations like #OpPayPal, which led to 19 arrests, could serve as a concrete counter-narrative to deter would-be recruits. In turn, social media companies could proactively apply community notes or contextual warnings, highlighting legal consequences.

Further, echoing lessons from suicide contagion studies, media outlets should avoid sensationalist reporting on cyberattacks that remain unconfirmed: this can make attacks seem more effective, encouraging both existing cyberhacktivists and possible recruits. Indeed, it’s worth noting that hacktivists are notorious for issuing threats that are ‘stronger than execution’, with success screenshots often contested by rival groups. Tech companies, whose recommendation algorithms can shape public perception, could further support these efforts by systematically de-amplifying unverified claims of cyberhacktivist attacks.

For policy practitioners, an intriguing, alternative solution lies in formalising cyber volunteerism. Case studies from Hungary and Estonia show the potential of folding high-risk populations into vetted cyber reserve programmes. While such initiatives are unlikely to divert individuals who have already been radicalised into ideologically extreme cyberhacktivist groups, they may be effective for ‘lurkers’, who are curious about using cybertools for political aims but whose grievances may not yet be strongly linked to a particular ideology. Indeed, though hacktivists are typically emotionally-driven, they also tend to be politically unsophisticated. Thus, offering institutional alternatives that confer status and a sense of purpose may absorb some of the momentum that might otherwise channel into cyberhacktivist contagions.

Reducing impact

As cyberhacktivist attacks grow more sophisticated and impactful, they move beyond nuisance to directly target individuals – for instance, workers in critical infrastructure industries. This necessitates socio-psychological interventions to reduce attack impact and strengthen cognitive security for possible targets.

When faced with ambiguous situations, humans attempt to resolve them by hyper-focusing. This can lead to the misdirection of effort and resources toward empty threats. For example, if a cyberhacktivist group were to spread misinformation about a planned future attack on a dam, ambiguity about whether the attack will occur creates hypervigilance among workers. In response, workers may regard any suspicious activity as malicious and potentially over-respond. From a strategic standpoint, this enables cyberhacktivists to consume bandwidth and induce disruption at virtually no cost: the mere threat of an attack becomes an attack of its own.

Drawing on findings from behavioural science, one effective intervention might involve rapid, transparent ‘pre-bunking’ of ambiguous stimuli. Studies have demonstrated that being introduced in advance to the tactics used by those spreading dis- and misinformation can have a ‘protective’ effect, akin to a vaccine. Thus, red teaming drills, which pre-emptively demonstrate this psychological vulnerability, could ‘inoculate’ key populations, such as system operators in critical infrastructure, against responding in a panicked way to ambiguous cyberhacktivist threats.

Conclusion

If cyberhacktivism continues its growth trajectory, it is imperative that we conceive of hacktivists not solely through a technical perspective, but a socio-psychological one too. Specifically, while evidence of social contagion is nascent, such a lens can clarify which individuals may be most vulnerable to recruitment and inform interventions to mitigate future risk.

—

Sonja Belkin is a first-year PhD candidate at the London School of Economics in the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science. Using empirical and computational methods, her research explores how user psychology, recommender systems, and AI-generated content interact to drive belief polarisation in online information environments. More broadly, she is interested in the intersection of cognitive psychology, technology, and security, particularly how to design and regulate information ecosystems, to make them resilient to AI-driven manipulation.

—

Are you a tech company interested in strengthening your capacity to counter terrorist and violent extremist activity online? Apply for GIFCT membership to join over 30 other tech platforms working together to prevent terrorists and violent extremists from exploiting online platforms by leveraging technology, expertise, and cross-sector partnerships.